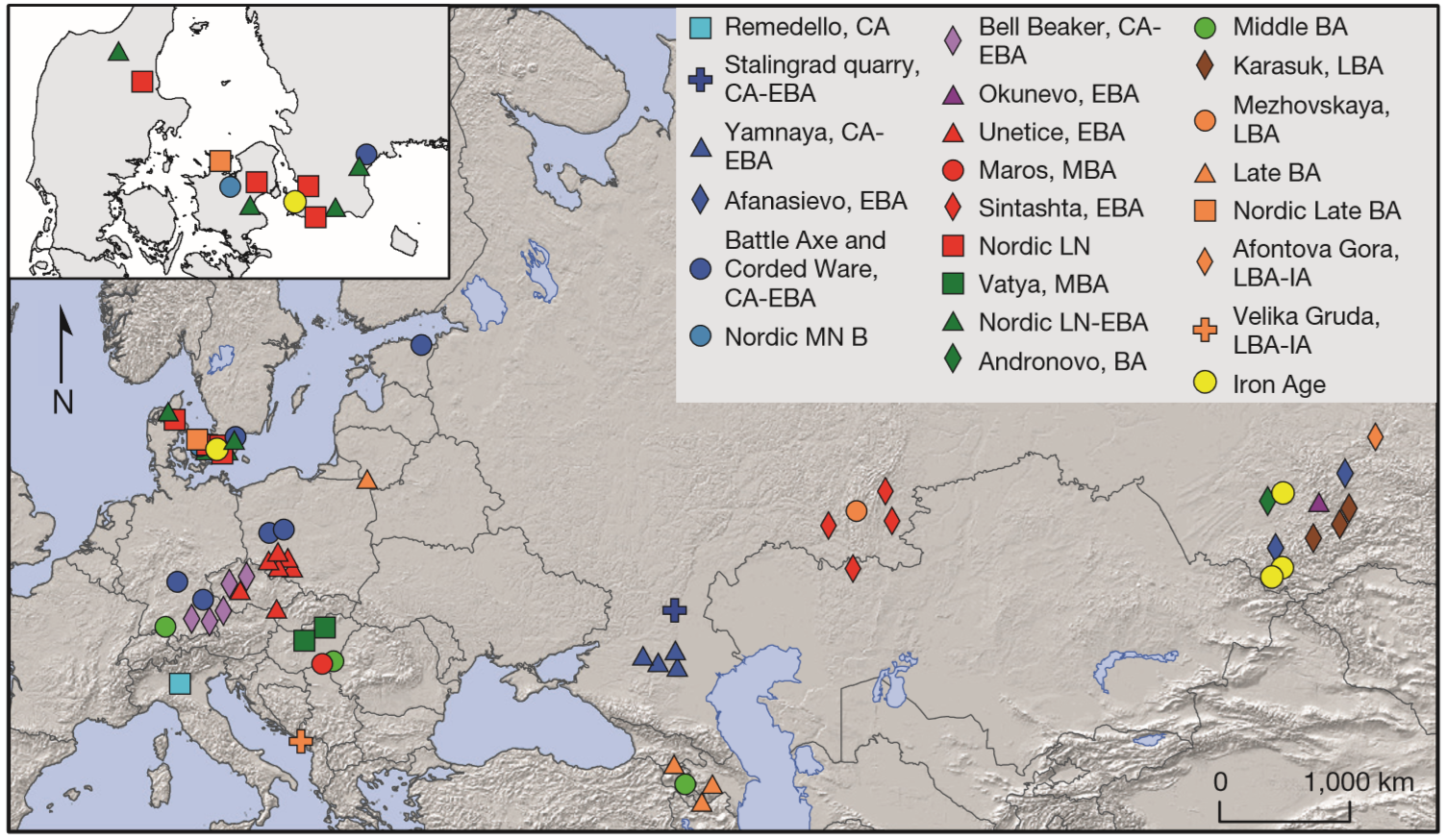

The archaeological record testifies to major cultural changes in

Europe and Asia after the Neolithic period. By 3000 BC, the

Neolithic farming cultures in temperate Eastern Europe appear to

be largely replaced by the Early Bronze Age Yamnaya culture, which

is associated with a completely new perception of family, property and

personhood13,14, rapidly stretching from Hungary to the Urals15. By

2800 BC a new social and economic formation, variously named

Corded Ware, Single Grave or Battle Axe cultures developed in temperate

Europe, possibly deriving from the Yamnaya background, and

culturally replacing the remaining Neolithic farmers16,17 (Fig. 1). In

western and Central Asia, hunter-gatherers still dominated in Early

Bronze Age, except in the Altai Mountains and Minusinsk Basin

where the Afanasievo culture existed with a close cultural affinity to

Yamnaya15 (Fig. 1). From the beginning of 2000 BC, a new class of

master artisans known as the Sintashta culture emerged in the Urals,

building chariots, breeding and training horses (Fig. 1), and producing

sophisticated new weapons18. These innovations quickly

spread across Europe and into Asia where they appeared to give rise

to the Andronovo culture19,20 (Fig. 1). In the Late Bronze Age around

1500 BC, the Andronovo culture was gradually replaced by the

Mezhovskaya, Karasuk, and Koryakova cultures21. It remains debated

if these major cultural shifts during the Bronze Age in Europe and

Asia resulted from the migration of people or through cultural diffusion

among settled groups15–17, and if the spread of the Indo-

European languages was linked to these events or predates them15.

Figure 1: Distribution maps of ancient samples. Localities, cultural associations, and approximate timeline of 101 sampled ancient individuals from Europe and Central Asia (left). Distribution of Early Bronze Age cultures Yamnaya, Corded Ware, and Afanasievo with arrows showing the Yamnaya expansions (top right). Middle and Late Bronze Age cultures Sintashta, Andronovo, Okunevo, and Karasuk with the eastward migration indicated (bottom right). Black markers represent chariot burials (2000–1800 bc) with similar horse cheek pieces, as evidence of expanding cultures. Tocharian is the second-oldest branch of Indo-European languages, preserved in Western China. CA, Copper Age; MN, Middle Neolithic; LN, Late Neolithic; EBA, Early Bronze Age; MBA, Middle Bronze Age; LBA, Late Bronze Age; IA, Iron Age; BAC, Battle Axe culture; CWC, Corded Ware culture.

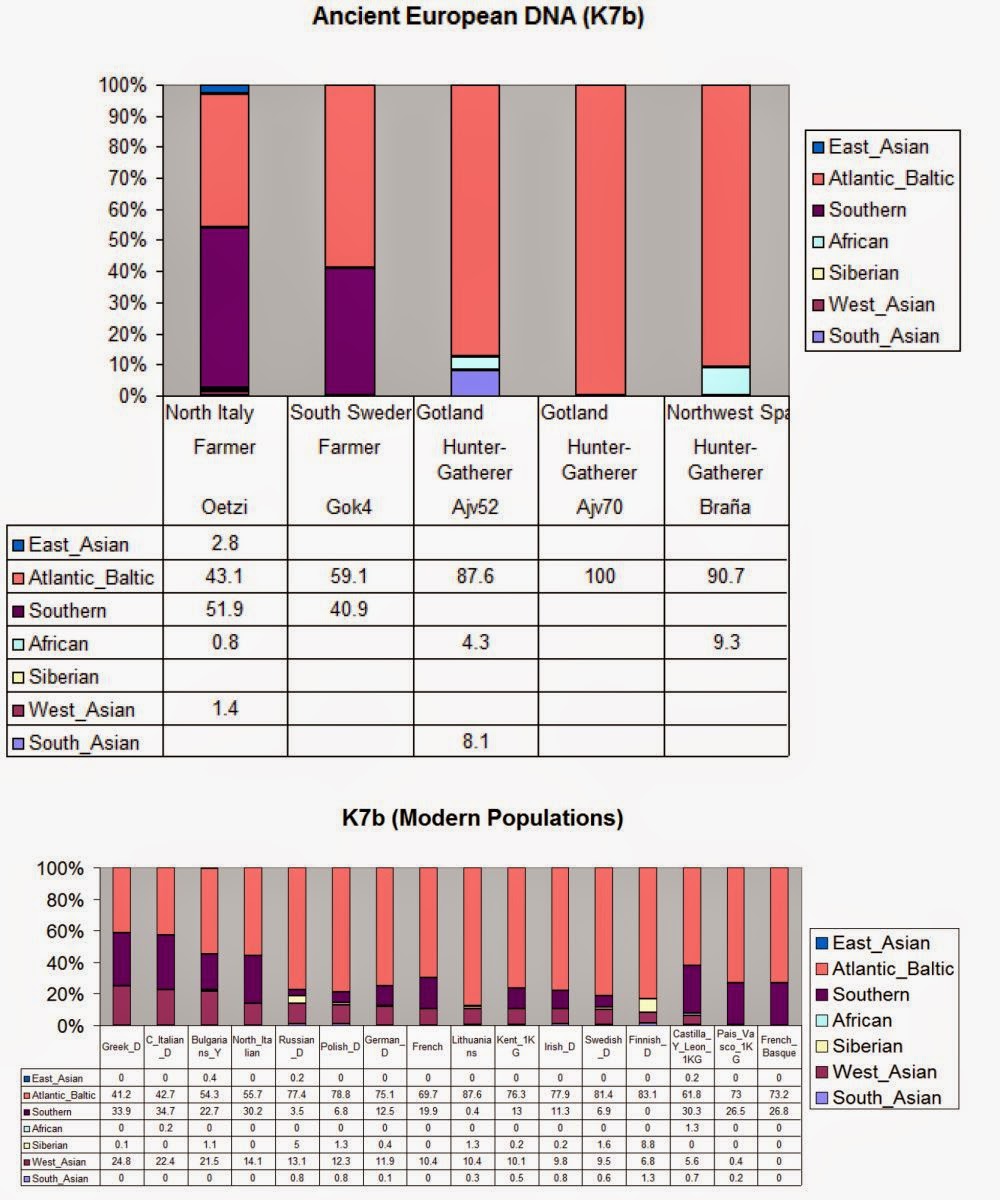

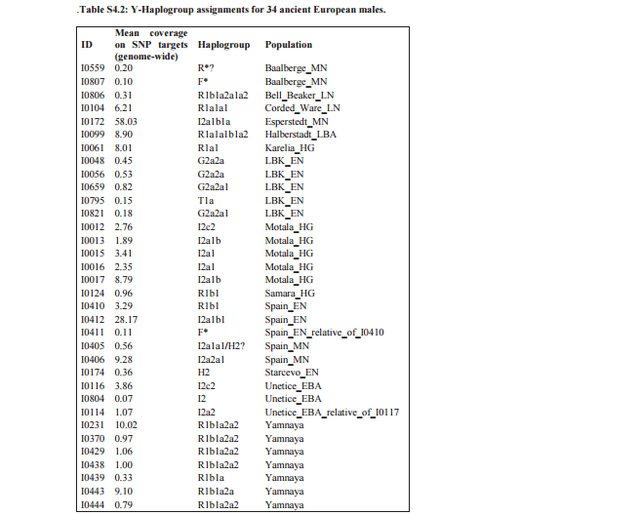

By analysing our genomic data in relation to previously published

ancient and modern data (Supplementary Information, section 6),

we find evidence for a genetically structured Europe during the

Bronze Age (Fig. 2; Extended Data Fig. 1; and Supplementary Figs 5

and 6). Populations in northern and central Europe were composed of

a mixture of the earlier hunter-gatherer and Neolithic farmer10

groups, but received ‘Caucasian’ genetic input at the onset of the

Bronze Age (Fig. 2). This coincides with the archaeologically welldefined

expansion of the Yamnaya culture from the Pontic-Caspian

steppe into Europe (Figs 1 and 2). This admixture event resulted in the

formation of peoples of the Corded Ware and related cultures, as

supported by negative ‘admixture’ f3 statistics when using Yamnaya

as a source population (Extended Data Table 2, Supplementary Table

12). Although European Late Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures such

as Corded Ware, Bell Beakers, Unetice, and the Scandinavian cultures

are genetically very similar to each other (Fig. 2), they still display a

cline of genetic affinity with Yamnaya, with highest levels in Corded

Ware, lowest in Hungary, and central European Bell Beakers being

intermediate (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 1). Using D-statistics,

we find that Corded Ware and Yamnaya individuals form a clade to

the exclusion of Bronze Age Armenians (Extended Data Table 1)

showing that the genetic ‘Caucasus component’ present in Bronze

Age Europe has a steppe origin rather than a southern Caucasus

origin. Earlier studies have shown that southern Europeans received

substantial gene flow from Neolithic farmers during the Neolithic9.

Despite being slightly later, we find that the Copper Age Remedello

culture in Italy does not have the ‘Caucasian’ genetic component and

is still clustering genetically with Neolithic farmers (Fig. 2; Extended

Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Hence this region was either

unaffected by the Yamnaya expansion or the Remedello pre-dates

such an expansion into southern Europe. The ‘Caucasian’ component

is clearly present during Late Bronze Age in Montenegro (Fig. 2b).

The close affinity we observe between peoples of Corded Ware and

Sintashta cultures (Extended Data Fig. 2a) suggests similar genetic

sources of the two, which contrasts with previous hypotheses placing

the origin of Sintastha in Asia or the Middle East28. Although we

cannot formally test whether the Sintashta derives directly from an

eastward migration of Corded Ware peoples or if they share common

ancestry with an earlier steppe population, the presence of European

Neolithic farmer ancestry in both the Corded Ware and the Sintashta,

combined with the absence of Neolithic farmer ancestry in the earlier

Yamnaya, would suggest the former being more probable (Fig. 2b and

Extended Data Table 1).

Figure 2: Genetic structure of ancient Europe and the Pontic-Caspian steppe. a, Principal component analysis (PCA) of ancient individuals (n = 93) from different periods projected onto contemporary individuals from Europe, West Asia, and Caucasus. Grey labels represent population codes showing coordinates for individuals (small) and population median (large). Coloured circles indicate ancient individuals b, ADMIXTURE ancestry components (K = 16) for ancient (n = 93) and selected contemporary individuals. The width of the bars representing ancient individuals is increased to aid visualization. Individuals with less than 20,000 SNPs have lighter colours. Coloured circles indicate corresponding group in the PCA. Probable Yamnaya-related admixture is indicated by the dashed arrow.

We find that the Bronze Age in Asia is equally dynamic and characterized

by large-scale migrations and population replacements. The

Early Bronze Age Afanasievo culture in the Altai-Sayan region is

genetically indistinguishable from Yamnaya, confirming an eastward

expansion across the steppe (Figs 1 and 3b; Extended Data Fig. 2b and

Extended Data Table 1), in addition to the westward expansion into

Europe. Thus, the Yamnaya migrations resulted in gene flow across

vast distances, essentially connecting Altai in Siberia with Scandinavia

in the Early Bronze Age (Fig. 1). The Andronovo culture, which arose

in Central Asia during the later Bronze Age (Fig. 1), is genetically

closely related to the Sintashta peoples (Extended Data Fig. 2c), and

clearly distinct from both Yamnaya and Afanasievo (Fig. 3b and

Extended Data Table 1). Therefore, Andronovo represents a temporal

and geographical extension of the Sintashta gene pool. Towards the

end of the Bronze Age in Asia, Andronovo was replaced by the

Karasuk, Mezhovskaya, and Iron Age cultures which appear multiethnic

and show gradual admixture with East Asians (Fig. 3b and

Extended Data Table 2), corresponding with anthropological and

biological research29. However, Iron Age individuals from Central

Asia still show higher levels of West Eurasian ancestry than contemporary

populations from the same region (Fig. 3b). Intriguingly, individuals

of the Bronze Age Okunevo culture from the Sayano-Altai

region (Fig. 1) are related to present-day Native Americans (Extended

Data Fig. 2d), which confirms previous craniometric studies30. This

finding implies that Okunevo could represent a remnant population

related to the Upper Palaeolithic Mal’ta hunter-gatherer population

from Lake Baikal that contributed genetic material to Native

Americans4.