|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 10, 2019 18:18:34 GMT

The Discovery Institute first published its “Scientific Dissent from Darwinism” list in The New York Review of Books in 2001 to challenge “false” claims from PBS’ series “Evolution.” PBS had claimed “virtually every scientist in the world believes the theory to be true.” But biologist Douglas Axe, director of the Biologic Institute, argued peer pressure is obscuring the truth. “Because no scientist can show how Darwin’s mechanism can produce the complexity of life, every scientist should be skeptical,” he said. “The fact that most won’t admit to this exposes the unhealthy effect of peer pressure on scientific discourse.” “The list of signatories now includes 15 scientists from the National Academies of Science in countries including Russia, Czech Republic, Brazil, and the United States, as well as from the Royal Society. Many of the signers are professors or researchers at major universities and international research institutions such as the University of Cambridge, London’s Natural History Museum, Moscow State University, Hong Kong University, University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine in France, Ben-Gurion University in Israel, MIT, the Smithsonian, Yale, and Princeton,” it noted. Marcos Eberlin, Ph.D., founder of the Thomson Mass Spectromety Laboratory and member of the National Academy of Sciences in Brazil, said in the report, “As a biochemist I became skeptical about Darwinism when I was confronted with the extreme intricacy of the genetic code and its many most intelligent strategies to code, decode, and protect its information.”  Michael Egnor, professor of neurosurgery and pediatrics at State University of New York, Stony Brook, said scientists “know intuitively that Darwinism can accomplish some things, but not others.” “The question is what is that boundary? Does the information content in living things exceed that boundary? Darwinists have never faced those questions,” he said. “They’ve never asked scientifically, can random mutation and natural selection generate the information content in living things.” |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 10, 2019 18:55:31 GMT

“There Are No Weaknesses” The nonexistence of scientific skepticism was only natural since, as Darwin lobbyist Eugenie Scott would say in 2009, “There are no weaknesses in the theory of evolution.” See here for the “The Top Ten Scientific Problems with Biological and Chemical Evolution.” What’s significant about the Dissent from Darwinism list is not so much the names and the institutions listed there but what they tell you about the many Darwin skeptics in the science world who wouldn’t dare sign. Scientists know the career costs that would come from publicly challenging evolutionary theory. Discovery Institute and its sister research lab, Biologic Institute, have welcomed refugees who were chased out of top spots in the research world. Douglas Axe, Günter Bechly, and Richard Sternberg are well known to Evolution News readers. Check out the Free Science website for other stories.  The Power of Groupthink The signers of the Dissent list have all risked their careers or reputations in signing. Such is the power of groupthink. The scientific mainstream will punish you if they can, and the media is wedded to its narrative that “the scientists” are all in agreement and only “poets,” “lawyers,” and other “daft rubes” doubt Darwinian theory. In fact, I’m currently seeking to place an awesome manuscript by a scientist at an Ivy League university with the guts to give his reasons for rejecting Darwinism. The problem is that, as yet, nobody has the guts to publish it. Other scientists, like the Third Way group or the researchers who met at the Royal Society in 2016, reject standard evolutionary theory but would not sign the Dissent list because they (mistakenly) think it conveys an even worse source of ritual contamination — the taint of intelligent design. In fact, the Dissent text doesn’t in any way imply support for ID, as the website’s FAQ page emphasizes. The simple observation that neo-Darwinism can’t explain the origin of complex life forms does not lead directly to a design inference. That is a separate argument with separate evidence. Every ID proponent is a Darwin doubter, but not every Darwin doubter is an ID proponent.  Nothing to Lose? But I understand why people fear to go public, even if they would seem to have nothing to lose. I recall a visit a colleague and I made to the office of a Nobel laureate in a relevant field who gruffly stated his own rejection of evolutionary theory but refused to say anything in public. He is not a young man. Given his senior status, you would think he’d have nothing to fear. Yet he was afraid. Some people don’t know when they should be afraid. Indeed, it’s a yearly thing at the Summer Seminars on Intelligent Design, held in Seattle primarily for undergraduate and graduate students, that we need to warn the participants not to take the perils lightly. They should not, for example, post news about the Seminar or photos of other students on social media. We’ve had panics about PhD students who acted incautiously. In fact, we had one just last week. But by the time you’ve advanced a little further in academic life, you likely know what’s good for you. Given all this – the fear of taint and reprisals – it follows inevitably that the 1,000+ names represent only the tip of a vast iceberg. For every name, you can assigner a multiplier. Would it be ten? A hundred? More? I don’t know.  A Skeptical “Underground” Physicist Brian Miller, Research Coordinator for the Center for Science & Culture, has written about what he calls an “underground” in academia. Again, ID sympathizers are a subset of Darwin skeptics. But Dr. Miller observed: A biologist in our network worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard. He recounted how about a quarter of the postdocs he encountered were at least sympathetic to design arguments, but none were willing to acknowledge their support publicly due to the likely repercussions. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 18, 2019 18:18:00 GMT

Researchers have discovered an array of fossilized footprints in an ancient sand dune in Gibraltar, the small British territory on the southwestern tip of the Iberian Peninsula. One of the prints, they suggest, may have been made by a Neandertal. If they are right, the find is highly significant: Only one other Neandertal track site is known, a set of 62,000-year-old footprints from Romania. And the Gibraltar print is reportedly much younger, in which case it could have been made by one of the last Neandertals ever to walk the Earth. But other experts are not so sure about that interpretation. The discovery figures into long-standing questions about when anatomically modern Homo sapiens colonized Europe and when the archaic Neandertals went extinct.  Analysis of the tracks revealed five types of prints in the dune. To identify which animals made them, Fernando Muñiz of the University of Seville in Spain and his colleagues studied the sizes and shapes of the prints, comparing them with other preserved tracks and correlating them with fossilized animal remains found elsewhere in Gibraltar. The tracks appear to come from several kinds of mammals, including elephant, deer and leopard. One of the prints, although poorly preserved, looked decidedly human—the impression revealed a right foot that was wider in the front than in the rear and had five aligned toes. And the size of the print hints it belonged to a young adolescent. But what species of human produced the track?  The print itself records physical characteristics associated with both Neandertals and modern humans—deciding between the two candidates on the basis of the size and shape of the print was impossible. So to zero in on the track maker, the researchers looked to the age and location of the footprint. The team dated the tracks to around 28,000 years ago using a technique known as optically stimulated luminescence, which can determine when sand grains were last exposed to sunlight. Previously researchers, including some members of the footprint team, have argued based on remains found elsewhere in Gibraltar that Neandertals lived in this region at that late date, surviving thousands of years longer there than anywhere else in their formerly extensive range across Eurasia. Ultimately, H. sapienssupplanted Neandertals and other archaic humans around the globe. But our species did not seem to have reached Gibraltar until rather late in the game. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 18, 2019 23:34:29 GMT

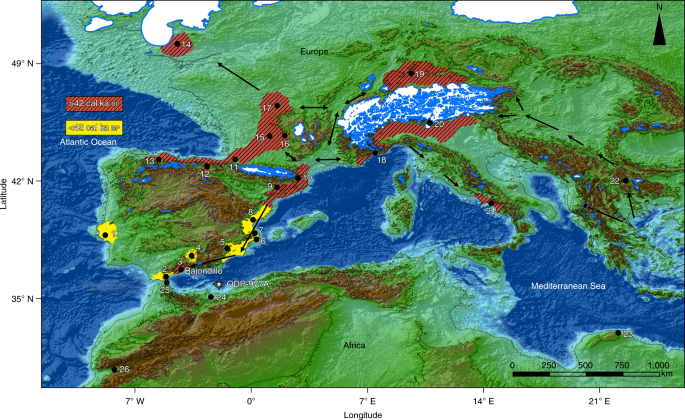

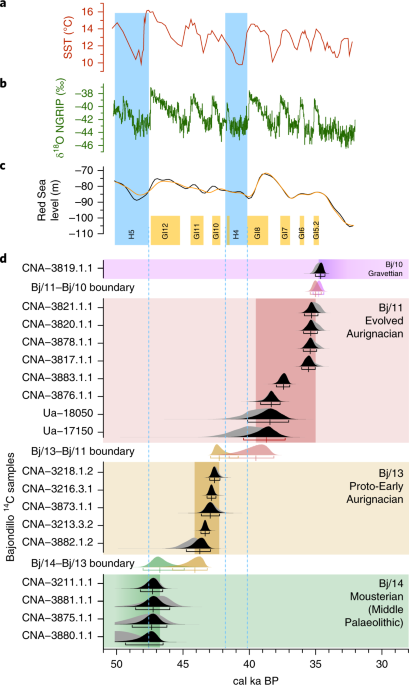

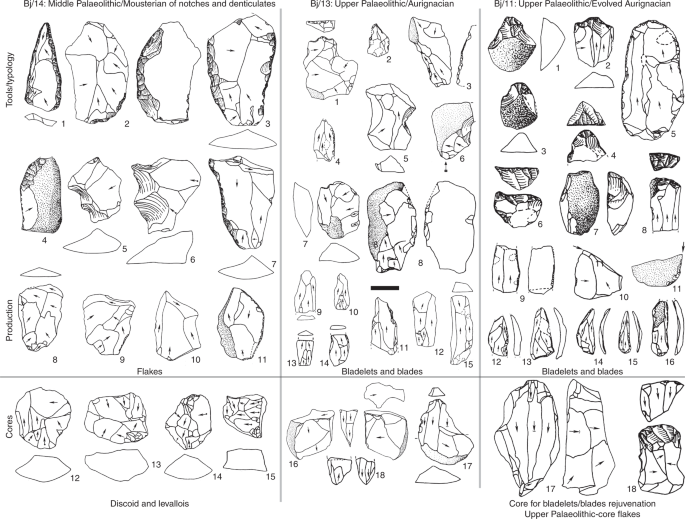

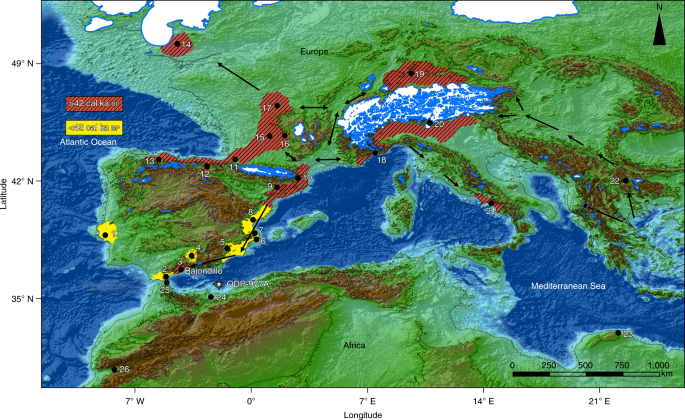

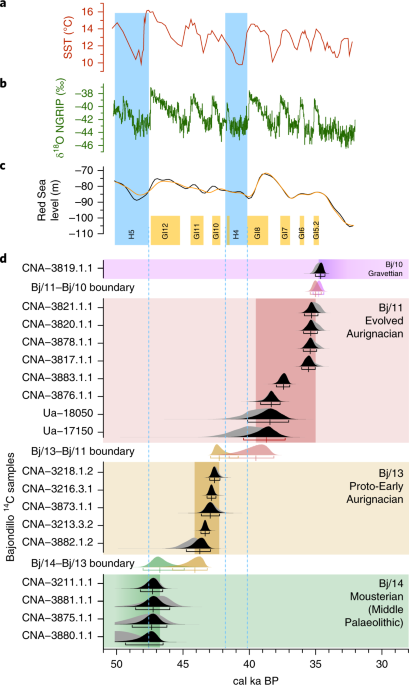

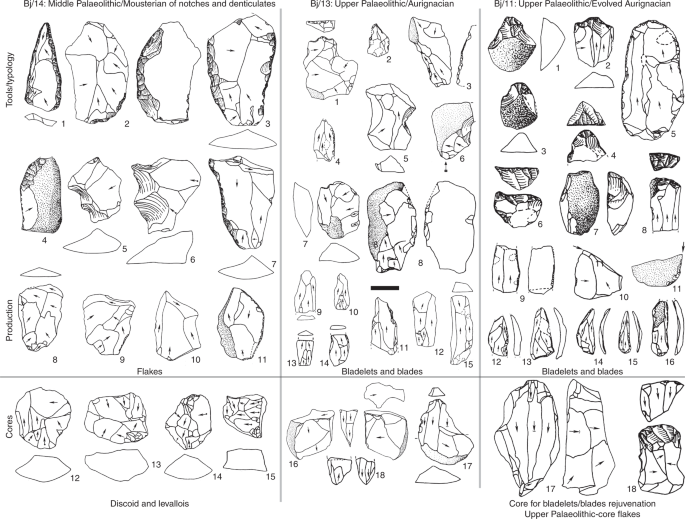

Westernmost Europe constitutes a key location in determining the timing of the replacement of Neanderthals by anatomically modern humans (AMHs). In this study, the replacement of late Mousterian industries by Aurignacian ones at the site of Bajondillo Cave (Málaga, southern Spain) is reported. On the basis of Bayesian analyses, a total of 26 radiocarbon dates, including 17 new ones, show that replacement at Bajondillo took place in the millennia centring on ~45–43 calibrated thousand years before the present (cal ka BP)—well before the onset of Heinrich event 4 (~40.2–38.3 cal ka BP). These dates indicate that the arrival of AMHs at the southernmost tip of Iberia was essentially synchronous with that recorded in other regions of Europe, and significantly increases the areal expansion reached by early AMHs at that time. In agreement with human dispersal scenarios on other continents, such rapid expansion points to coastal corridors as favoured routes for early AMH. The new radiocarbon dates align Iberian chronologies with AMH dispersal patterns in Eurasia.  The new Bajondillo dates are crucial for several reasons. First, they confirm the presence of a chronologically early Aurignacian in southern Iberia at ~43 cal ka that now shows the first appear-ance of the EUP to be an essentially synchronous event throughout Europe (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3). This suggests that the dis-persal of AMHs was much faster than hitherto postulated, and the expansion of the earliest Aurignacians in Europe is now increased westwards by > 1,000 km. These dates thus call into question both the gradual ‘wave-of-advance’ and the ‘Ebro frontier’ models. They also provide reference points for the attribution of early art work in Iberian caves—something that remains highly controversial35. The dates suggest either extremely high mobility of early Aurignacians or well-developed networks of interchange. For early AMHs, rapid dispersal was seemingly only possible over essentially ‘empty’ terri-tories (that is, either completely depopulated areas, as some studies suggest for southern Iberia at the time7, or areas featuring severely depleted human populations).  Fig. 3: Comparison between the chronologies of the different archaeological levels at Bajondillo Cave and a selection of palaeoenvironmental proxies. The Aurignacian early expansion took place between Heinrich events 5 and 4 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3), when cold and steppic conditions prevailed throughout most of western Europe, including the Iberian hinterland36. In light of this, it might be no coincidence that a prevalence of European EUP sites has been reported along shores or neighbouring lowlands where milder con-ditions prevailed and more productive environments, in terms of living resources, existed (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2c). The Aurignacian from Bajondillo Cave conforms with this pattern and is not an isolated case in Iberia, where newly recorded Aurignacian sites south of the Ebro river, such as Foradada16, Cendres17 and Pego do Diabo12, are all located on the present-day coast or its adjoin-ing lowlands (Fig. 1), nor in Italy (Riparo Mochi and Serino; see Supplementary Information). Coasts and coastal lowlands as instrumental for human dispersal and colonizing events are not a phenomenon restricted to the European Aurignacian, since data emerging from southern Arabia37, Australia38,39 and South America40 all point in the same direction. In eastern and southern Iberia, trav-elling through coasts and coastal lowlands would have been con-siderably easier than travelling through one of the most rugged and mountainous hinterlands in Europe. The enhanced mobility of Aurignacian populations can be inferred from their swift spread over western Europe from Glacial Interstadial 12 onwards, thus hinting at dispersals taking place across territories that were easy to traverse (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b)1.  The onset of the Aurignacian cannot be detached from the demise of the Neanderthals. Inferences about the mobility and settlement patterns of southern Iberian Neanderthals are compli-cated due to the restricted number of Mousterian sites, as well as the prevalence of low sea-level stands during this period, which means that an undetermined, yet probably substantial, fraction of the evidence presently lies underwater. From this perspective Bajondillo Cave is of great relevance since, due to its topogra-phy, it was at all times located on or very close to the shore (that is, not more than 5 km distant; Supplementary Fig. 2a), but never flooded. The data from Bajondillo Cave and other coastal Iberian locations41 reveal that stasis, as exemplified by around 120 kyr14 of Neanderthal occupation with no clear traces of technological devel-opments, prevailed during the Iberian Mousterian. Similar trends are also documented—albeit in in a more restricted manner—at the Abrigo 3 (ref. 21) and Gorham’s Cave sites11. All constitute evi-dence that Neanderthals were settled along the coast well before the onset of the Aurignacian. Although the Bajondillo Cave dates do not indicate any coexistence of Neanderthals and Aurignacians, the fact that the Middle Palaeolithic ceases at around 45 cal ka (Supplementary Table 1) is also worth noting. Indeed, this date is essentially synchronous with the cessation of Middle Palaeolithic levels from sites in the province of Málaga, both coastal (Abrigo 3)21 and inland (Zafarraya)22. The idea of a regional, as opposed to local, phenomenon seems compelling, as is the fact that (except for the two Bay of Málaga sites) Late Mousterian settlements are located at a substantial altitude (that is, > 400 m). A putative preferential location of late Neanderthal sites on harsher and less productive habitats than the coastal zones where older Middle Palaeolithic sites occur and the earliest AMH sites are recorded hints at a scenario of competitive displacement of Neanderthals by AMHs. This com-plex issue is difficult to address when a substantial proportion of the available evidence is circumstantial. In contrast, genetic data may help confirm whether Neanderthal replacement was determined by competition, migration and random species drift or if, as also seems possible, AMHs and Neanderthal gene pools coalesced after episodes of introgression42. However, it is notable that none of the European late Neanderthal genomes sequenced so far shows evi-dence of interbreeding with AMHs43.Recent reviews highlighting the genetic complexities that under-lie AMH expansion in Eurasia tend to focus on data from Asia, and fail to consider the possibility that a crucial part of that evidence may lie on the westernmost tip of the Mediterranean2. Given the relevance of the palaeoanthropological and archaeological data that are slowly emerging from this region, further efforts to determine whether coastal dispersals played a major role in the arrival of mod-ern humans in the region are crucial. Given the growing evidence that humans were also capable of crossing bodies of water before 50 cal k 2, investigation into whether the Strait of Gibraltar played any role as a connector of European Neanderthals and North African AMHs is also a promising area of research. It is within this interpretative framework that the presence of an early Aurignacian at Bajondillo Cave may bear wider implications for the origin of Upper Palaeolithic industries and the appearance of AMHs in the European subcontinent than can be foreseen now. Nature Ecology & Evolutionvolume 3, pages207–212 (2019) |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 19, 2019 17:27:51 GMT

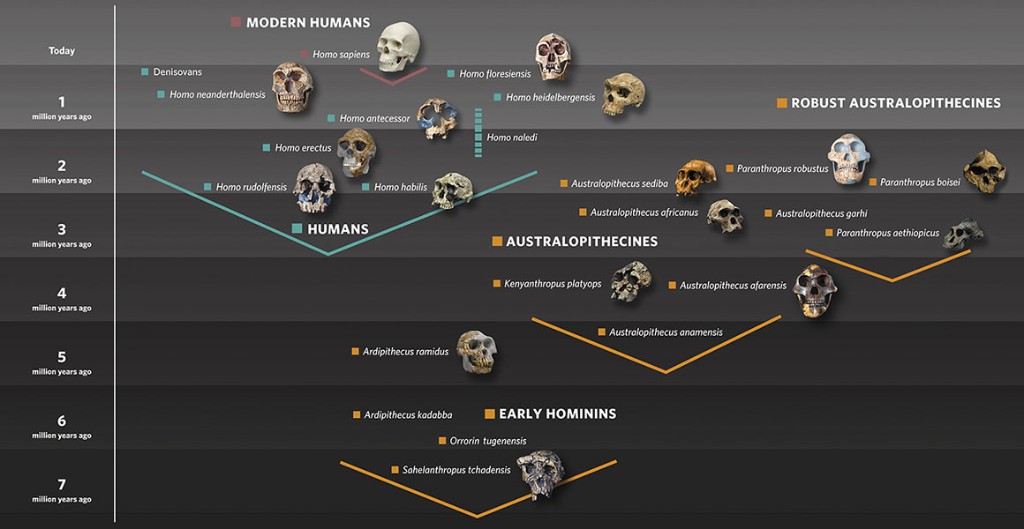

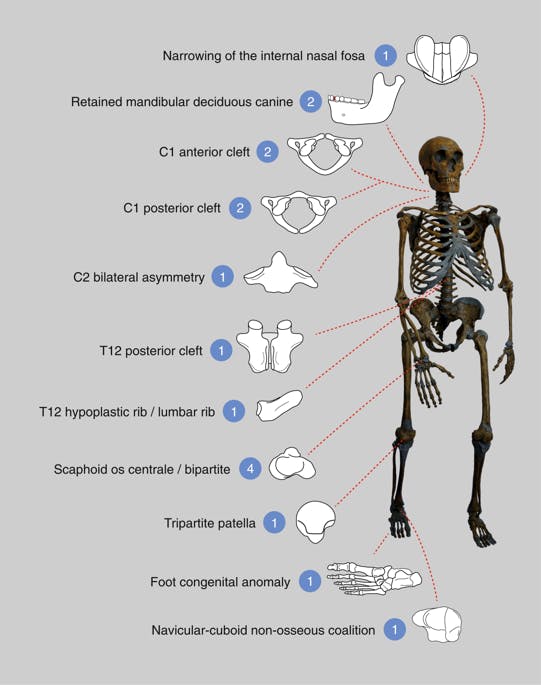

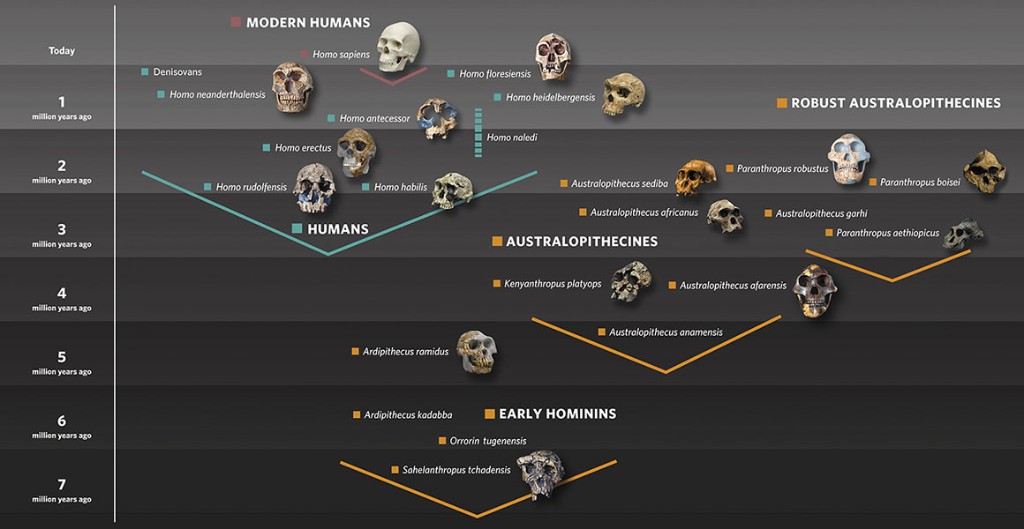

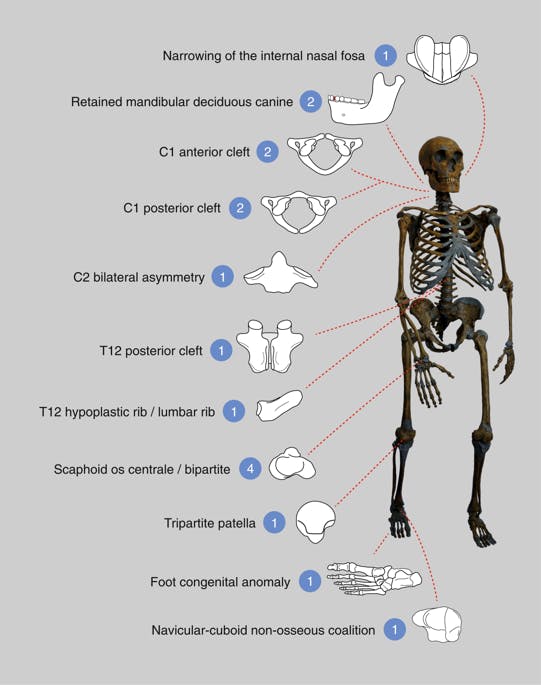

Homo sapiens are the only humans left on Earth. But thousands of years ago there were more of us — other species that belonged to the same genus, and in turn, our family tree. They are now extinct and scientists endeavor to figure out why. In a new study published this month in Scientific Reports, a team took on the case of Homo neanderthalensis, and argue that the reason they died out was because things turned a little Game of Thrones.  In the study, scientists examined skeletal specimens that belonged to 13 Neanderthals that lived in a site called Sidrón Cave in northwestern Spain around 49,000 years ago. Meanwhile, the demise of the Neanderthals happened around 40,000 years ago — just 9,000 years after these individuals were living together, attempting to survive. It’s previously been established that there was at least some inbreeding, or mating among relatives, in Neanderthal groups and that specimens discovered at the Sidrón site belonged to the same kin group. This study is the first to specifically examine the skeletons found there for signs of inbreeding. Overall, they found 17 cases of congenital anomalies — instances where, for example, vertebras were cleft, canine teeth grew with cysts, and nasal passages were unusually narrowed.  These anomalies, the study authors argue are genetic and skeletal evidence that inbreeding happened in Sidrón, a fact they write that “could be representative of the beginning of the demographic collapse of this hominin phenotype.” Neanderthal bans were notoriously small, and while other factors may have influenced their demise, the team here argues that it’s not “unreasonable to suggest” that demographic differences in population size and density played a role in their disappearance, writing: “The disappearance of the Neanderthals and expansion of modern humans was most probably the result of a process involving several factors, one of them being the low population density of Neanderthals.” Dennis Sandgathe, Ph.D. is a professor of archeology at Simon Fraser University and studies the technology used by and behavior of the Neanderthals. He was not a part of this study and when asked by Inverse to review the paper, he noted that he’s cautious about the argument. Significant homozygosity — getting the same version of a gene from mom and dad — has been noted in a number of Neanderthal DNA, which Sandgathe says “does indicate that they were regularly mating with closely related individuals and this may well have a direct connection to their disappearance.” Abstract: Neandertals disappeared from the fossil record around 40,000 bp, after a demographic history of small and isolated groups with high but variable levels of inbreeding, and episodes of interbreeding with other Paleolithic hominins. It is reasonable to expect that high levels of endogamy could be expressed in the skeleton of at least some Neandertal groups. Genetic studies indicate that the 13 individuals from the site of El Sidrón, Spain, dated around 49,000 bp, constituted a closely related kin group, making these Neandertals an appropriate case study for the observation of skeletal signs of inbreeding. We present the complete study of the 1674 identified skeletal specimens from El Sidrón. Altogether, 17 congenital anomalies were observed (narrowing of the internal nasal fossa, retained deciduous canine, clefts of the first cervical vertebra, unilateral hypoplasia of the second cervical vertebra, clefting of the twelfth thoracic vertebra, diminutive thoracic or lumbar rib, os centrale carpi and bipartite scaphoid, tripartite patella, left foot anomaly and cuboid-navicular coalition), with at least four individuals presenting congenital conditions (clefts of the first cervical vertebra). At 49,000 years ago, the Neandertals from El Sidrón, with genetic and skeletal evidence of inbreeding, could be representative of the beginning of the demographic collapse of this hominin phenotype. Scientific Reportsvolume 9, Article number: 1697 (2019) |

|