|

|

Post by Admin on May 24, 2020 23:59:20 GMT

Editor's note: The Wuhan Institute of Virology has been in the eye of the storm since the novel coronavirus, later known as COVID-19, engulfed the world. Leaving almost nowhere untouched, the virus of unknown etiology has so far infected over 5 million people globally, with a death toll exceeding 338,000. It has forced shutdowns worldwide, crippling economies and upending lives overnight.

Since the first known cases were reported last December, scientists have raced to find the origins of the virus in the hope of developing a vaccine. In the meantime, a blame game is going on, with conspiracy theories ranging from the virus "leaking" from the Wuhan Institute of Virology to China "concealing" crucial information, despite repeated claims from scientists that it originated from nature.

CGTN spoke to Wang Yanyi (Wang), an immunologist and director of the institute, to get her take on these rumors, how she views the outbreak and the progress in cooperating with her international counterparts.

CGTN: Since the outbreak began, there has been speculation that the novel coronavirus leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. How do you respond to that?

Wang: This is pure fabrication. Our institute first received the clinical sample of the unknown pneumonia on December 30 last year. After we checked the pathogen within the sample, we found it contained a new coronavirus, which is now called SARS-CoV-2. We didn't have any knowledge before that, nor had we ever encountered, researched or kept the virus. In fact, like everyone else, we didn't even know the virus existed. How could it have leaked from our lab when we never had it?

CGTN: An article published in the periodical Nature in April 2018 mentioned a novel coronavirus originating from bats. And this coronavirus was in your lab. Is this the virus that caused the pandemic?

Wang: In fact, many coronaviruses are called "novel" when they are first discovered, such as MERS (the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), the one you mentioned and SARS-CoV-2. They were all called novel coronaviruses when they were first discovered, which may cause confusion. Actually, the virus mentioned in the 2018 article wasn't SARS-CoV-2. The virus in the article mainly causes diarrhea and death among piglets. It was later named SADS. The genome sequence of SADS is only 50 percent similar to that of SARS-CoV-2. It's a rather big difference.

CGTN: But in February, the institute published another article in Nature saying you found another novel coronavirus from bats. The similarity between this virus and the SARS-CoV-2 is up to 96.2 percent, which is relatively high. Could it be the source of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Wang: The bat coronavirus you mentioned which has a 96.2 percent genomic similarity to SARS-CoV-2 is called RaTG-13. From the perspective of many non-professionals, the similarity rate of 96.2 percent is a very high number. But coronavirus is one of the RNA viruses that have the largest genomes.

Take the SARS-CoV-2 for example. Its entire genome contains about 30,000 bases. The difference of a percentage of 3.8 means the difference of over 1,100 nucleotide positions. In the natural world, it takes a long period of time for a virus to naturally evolve and mutate to become SARS-CoV-2.

Recently we've noticed a statement made by Edward Holmes, a world-leading virologist who studies the evolution of viruses. He believes it would take about 50 years for RaTG-13 to naturally evolve to SARS-CoV-2. The difference of over 1,100 positions is huge. And they should respectively match the corresponding nucleotide positions in the genome of SARS-CoV-2, which means it requires more than 1,100 mutations in these exact positions to become SARS-CoV-2. Thus, the probability is very low.

Many people might misunderstand that since our institute reported the RaTG-13's genomic similarity to SARS-CoV-2, we must have the RaTG-13 virus in our lab. In fact, that's not the case. When we were sequencing the genes of this bat virus sample, we got the genome sequence of the RaTG-13 but we didn't isolate nor obtain the live virus of RaTG-13. Thus, there is no possibility of us leaking RaTG-13.

CGTN: You said the institute didn't have the SARS-CoV-2 nor the live virus of RaTG-13. Since the Wuhan Institute of Virology has been researching coronaviruses, don't you have any live viruses? What does your virus collection center have?

Wang: Earlier you talked about some research teams from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. One of the teams led by Professor Shi Zhengli began studying bat coronaviruses in 2004. But its research has been focused on source tracing of SARS. In their research what they pay more attention to, do more research on and try to isolate and obtain are bat coronaviruses similar to the one that caused SARS.

We know that the entire genome of SARS-CoV-2 is only 80 percent similar to that of the SARS virus. It's an obvious difference. So, in Professor Shi's past research, the team didn't pay attention to such viruses which are less similar to the SARS virus. This is why they didn't try to isolate and obtain RaTG-13, since its genome is only over 79 percent similar to that of the SARS virus.

After many years of research, Professor Shi and her team have isolated and obtained some coronaviruses from bats. Now we have three strains of live viruses. One of them has the highest similarity, 96 percent to the SARS virus. But their highest similarity to SARS-CoV-2 only reaches 79.8 percent.

CGTN: The Wuhan Institute of Virology has been devoted to studying coronaviruses since the SARS outbreak. You've made a lot of effort to track the viruses. After the COVID-19 outbreak began, which is due to a brand new virus, what have you done to track its origin?

Wang: The current consensus of the international academic community is that the virus originated from wild animals. But we still don't clearly know what kind of viruses that all different wild species carry across the globe and where the viruses that are highly similar to SARS-CoV-2 are. This is why the cooperation between scientists all over the world is needed to find the answers. Therefore, the issue of origin-tracking is ultimately a question of science, which requires the scientists to make judgments based on scientific data and facts.

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 5, 2020 1:10:38 GMT

On May 15, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists published a short commentary titled, “Let evidence, not talk radio, determine whether the outbreak started in a lab,” by Ali Nouri, a biologist and president of the Federation of American Scientists. “The outbreak” referred to the pandemic of SARS-CoV-2 now circling the globe. It is a thin commentary, and it is puzzling why the Bulletin thought it desirable to publish it at all. Only two weeks earlier the journal had published a reasoned and competent appraisal by Kings College London biosecurity expert Filippa Lentzos titled, “Natural spillover or research lab leak? Why a credible investigation is needed to determine the origin of the coronavirus pandemic.”  The Nouri article very correctly pilloried the statements by President Donald Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, presidential legal advisor Rudy Giuliani, and radio personality Rush Limbaugh. These are as notorious a gang of four fabricators as will ever likely be recorded in American history. They were ably assisted by Fox News, which the Nouri critique also mentions. Nouri ended his commentary with these lines: “Our leaders ought to … take steps to prevent the next pandemic, instead of diverting our attention to unsupported sensationalist theories spread by cable TV and talk radio.” Perhaps the most damaging blows to efforts to obtain a certain answer as to the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 “outbreak” have been the pronouncements by Trump, Pompeo, and their echo chambers. But they and their remarks are not the measure by which the question of the possibility that a laboratory escape began the pandemic should be examined. Trump’s diversionary ranting comes from a president who did nothing for two months in the face of an oncoming lethal pandemic, actively denied and denigrated intelligence warnings of the imminent danger, and said that SARS-CoV-2 would “just go away … like a miracle” and that “within a couple of days is going to be down close to zero.” All this has been widely and thoroughly chronicled.1 But long before Trump, Pompeo and Co. sought a Chinese scapegoat for the president’s gross and willful incompetence, researchers understood that the possibility of laboratory escape of the pathogen was a plausible, if unproven, possibility. It is most definitely not “a conspiracy theory.”  The circumstantial evidence for a lab escape. By way of introduction, there are two virology institutes in Wuhan to consider, not one: The Wuhan Center for Disease Control and Prevention (WHCDC) and the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). Both have conducted large projects on novel bat viruses and maintained large research collections of novel bat viruses, and at least the WIV possessed the virus that is the most closely related known virus in the world to the outbreak virus, bat virus RaTG13. This virus was isolated in 2013 and had its genome published on January 23, 2020. Seven more years of bat coronavirus collection followed the 2013 RaTG13 isolation. One component of the novel-bat-virus project at the Wuhan Institute of Virology involved infection of laboratory animals with bat viruses. Therefore, the possibility of a lab accident includes scenarios with direct transmission of a bat virus to a lab worker, scenarios with transmission of a bat virus to a laboratory animal and then to a lab worker, and scenarios involving improper disposal of laboratory animals or laboratory waste. Documentary evidence indicates that the novel-bat-virus projects at Wuhan CDC and the Wuhan Institute of Virology used personal protective equipment and biosafety standards that would pose high risk of accidental infection of a lab worker upon contact with a virus having the transmission properties of the outbreak virus. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 5, 2020 7:00:56 GMT

In assessing the possibility of a lab accident, one must take into consideration each of the following eight elements of circumstantial evidence:

1. Official Chinese government recognition early in the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak of biosafety inadequacies in China’s high containment facilities. In February 2020, several weeks after the outbreak of the disease in Wuhan, China’s President Xi Jinping stressed the need to ensure “biosafety and biosecurity of the country.”2 This was followed immediately by a China Ministry of Science & Technology announcement of new guidelines for laboratories, especially in handling viruses.3 Almost at the same time, the Chinese newspaper Global Times published an article on “chronic inadequate management issues at laboratories, including problems of biological wastes.”4

A PBS NewHour presentation on May 22, 2020 provided the following information:

On January 1, Wuhan Institute of Virology’s director general, Yanyi Wang, messaged her colleagues, saying the National Health Commission told her the lab’s COVID-19 data shall not be published on social media and shall not be disclosed to the media. And on January 3, the commission sent this document, never posted online, but saved by researchers, telling labs to destroy COVID-19 samples or send them to the depository institutions designated by the state. Late Friday [May 16, 2020] the Chinese government admitted to the destruction … but said it was for public safety.

The Chinese government explanation for the destruction of SARS-CoV-2 samples has no scientific credibility. For purposes of “public safety” any samples would surely be stored and studied, exactly as with the ones that were isolated from patients, and their RNA genomes decoded and published.

2. Recognition by Zhengli Shi, a renowned scientist who leads a research team at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, that a laboratory escape was a possibility. Shi took the possibility of a laboratory escape perfectly seriously. Jonna Mazat of the University of California-Davis, a collaborator with Dr Shi, told Josh Rogin of the Washington Post, “Absolutely, accidents can happen.” In an interview with Scientific American, Shi admitted that her very first thought was “If coronaviruses were the culprit, she remembers thinking ‘Could they have come from our lab?’”

Meanwhile she frantically went through her own lab’s records from the past few years to check for any mishandling of experimental materials, especially during disposal. She breathed a sigh of relief when the results came back: none of the sequences matched those of the viruses her team had sampled from bat caves. ‘That really took a load off my mind,’ she says. ‘I had not slept a wink for days.’

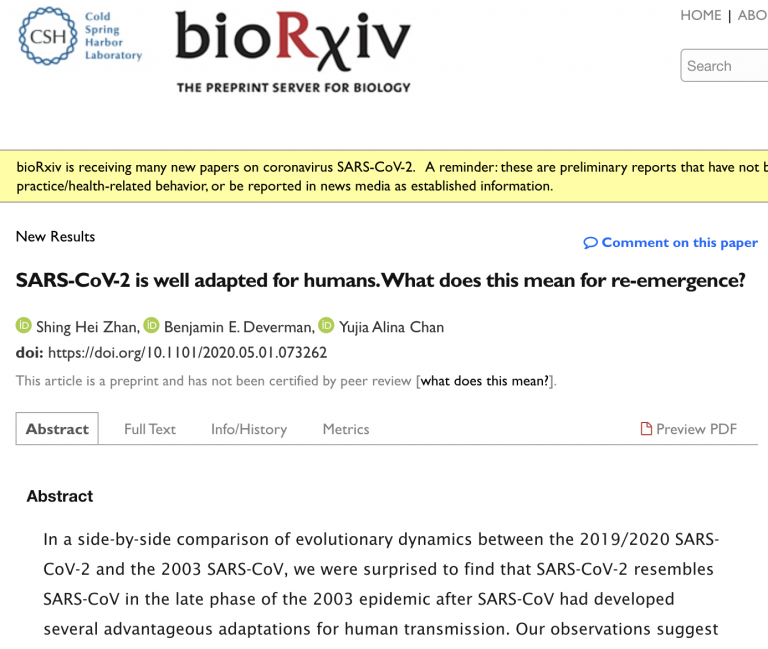

3. Questions surrounding Chinese government attribution of the Wuhan’s Huanan South China Seafood Market as the source of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Many China scholars noted that it was quite unusual for Chinese government authorities to identify Wuhan’s Huanan South China Seafood Market so quickly as the source of the outbreak. They thought this behavior so uncharacteristic that it raised suspicions in their minds. The authors of a newly published paper wrote that

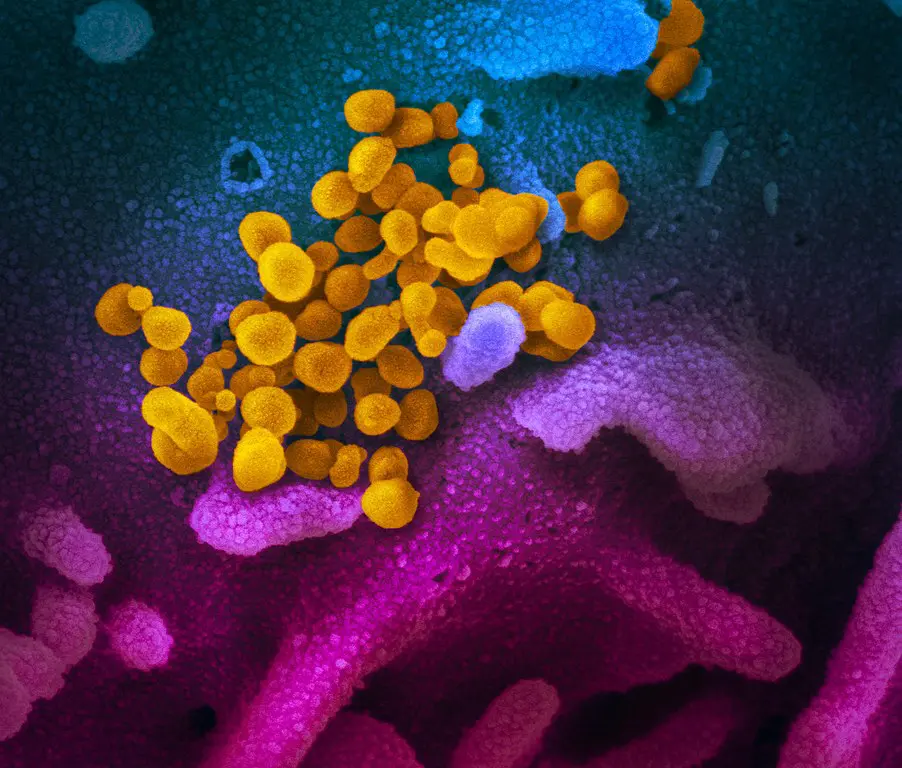

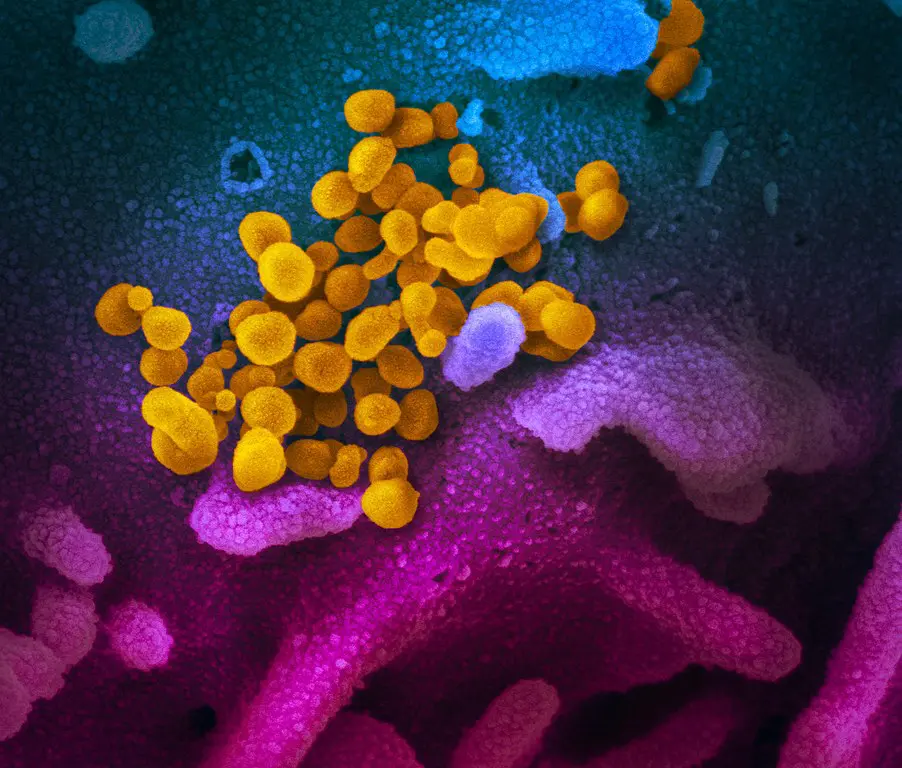

…we were surprised to find that SARS-CoV-2 resembles SARS-CoV in the late phase of the 2003 epidemic after SARS-CoV had developed several advantageous adaptations for human transmission. Our observations suggest that by the time SARS-CoV-2 was first detected in late 2019, it was already pre-adapted to human transmission to an extent similar to late epidemic SARS-CoV. However, no precursors or branches of evolution stemming from a less human-adapted SARS-CoV-2-like virus have been detected…. It would be curious if no precursor or branches of SARS-CoV-2 evolution are discovered in humans or animals….Even the possibility that a non-genetically-engineered precursor could have adapted to humans while being studied in a laboratory should be considered, regardless of how likely or unlikely.5

It is important to note that no intermediary host has yet been identified for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The authors also noted that “[n]o animal sampling prior to the shutdown and sanitization [of the Wuhan fish market] was done.”

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 5, 2020 19:16:36 GMT

The question of whether the index case appeared in the Wuhan fish market appears to be moot in any case. Chinese researchers have published data showing that there were 41 cases of SARS-CoV-2 between December 1, 2019 and January 2, 2020. Fourteen of these had no contact with the Huanan seafood market, including the very first recorded case on December 1, 2019.6 And that supposes that the true index case was December 1, which is doubtful. On May 26, the Chinese government scrapped the previous official story about the Wuhan fish market: China’s top epidemiologist said Tuesday that testing of samples from a Wuhan food market, initially suspected as a path for the virus’s spread to humans, failed to show links between animals being sold there and the pathogen. Gao Fu, director of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said in comments carried in China state media.7 No SARS-CoV-2 isolates were detected in any of the animals or fish sold at the market, only in environmental samples, including sewage. Gao Fu added, “At first, we assumed the seafood market might have the virus, but now the market is more like a victim. The novel coronavirus had existed long before.”8 4. Suppression of information and individuals by Chinese authorities. A publication by two Chinese university academics discussed both the WHCDC and the WIV and concluded that “the killer coronavirus probably originated from a laboratory in Wuhan”; the publication was removed from the internet by Chinese government officials. The paper had been posted on Research Gate but was blocked after 24 hours. After being placed on an archive file by internet users, it was again blocked after a week, and the two Chinese authors were pressured to retract the paper. However, it is still available on Web archives.9 The Chinese government closed the laboratory in Shanghai that first published the genome of COVID-19 on January 10, explaining that it had been shuttered for “rectification”; the closure happened on January 11. The government then permitted the same genome to be published by Shi on January 12.10 Chinese citizens who reported on the coronavirus were censured and, in some cases, “disappeared.”11 These have included businessman Fang Bin, lawyer Chen Qiushi, former state TV reporter Li Zehua and, most recently, Zhang Zhan, a lawyer. They are reportedly being held in extrajudicial detention centers for speaking out about China’s response to the pandemic. They are usually accused of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.”12 Another aspect of Chinese government secrecy involved in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic relates to official reporting by Chinese government officials on the severity of the outbreak in China and on levels of mortality. The number of cases and deaths are suspected of being undercounted by at least an order of magnitude, and possibly two, meaning that the reported figures could be as little as one percent of the actual totals. In the last week of April 2020, Caixin, one of the most reliable publications in China, reported that a serological study had been carried out in Wuhan on 11,000 inhabitants. Extrapolating from its results, which showed that five to six percent of the sample of 11,000 persons carried antibodies for SARS-CoV-2, Caixin estimated that 500,000 people in the city had been infected, or 10 times the level of official Chinese government reporting. The publication was quickly deleted by Chinese government censors.13 The Chinese government has also attempted to obscure the origins of the pandemic with disinformation. On March 13, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian suggested that the United States might have introduced the coronavirus to Wuhan.14 A month later, Zhao Lijian again posted Russian coronavirus and biowarfare-related disinformation, this time followed by online posts from Chinese ambassadors in 13 countries spread across the world.15 This was unprecedented diplomatic behavior for China, but not an accident. It was a concerted, deliberate, and preposterous disinformation campaign, repeated in May by CGTN, the China Global Television Network, which reposted the disinformation to the social media sites Weibo, Facebook, and Twitter.16 The history of Soviet and then Russian government biowarfare disinformation suggests that a country spreading such disinformation has or may have something to hide.17 5. Laboratory accidents and the escape of highly dangerous pathogens from laboratories are frequent occurrences worldwide. The accidental infection of researchers in the highest containment biosafety facilities—labelled BSL-2, BSL-3 and BSL-4—occurs worldwide, as do accidental releases by other means. In an excellent review published in February 2019, Lynn Klotz of the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation noted that three releases of Ebola and Marburg viruses from BSL-4 and lower-containment facilities in the United States had occurred due to incomplete inactivation of cultures. Releases via infection of researchers took place in the highest containment facilities in the United States—at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta and at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID)—but in all cases only the researcher became ill, and there was no further transmission of the pathogen. “In an analysis circulated at the 2017 meeting for the Biological Weapons Convention, a conservative estimate shows that the probability is about 20 percent for a release of a mammalian-airborne-transmissible, highly pathogenic avian influenza virus into the community from at least one of 10 labs over a 10-year period of developing and researching this type of pathogen,” Klotz wrote. “This percentage was calculated from FSAP [US Federal Select Agent Program] data for the years 2004 through 2010. Analysis of the FOIA NIH (National Institutes of Health) data gives a much higher release probability—that is, a factor five to 10 times higher, based on a smaller number of incident reports.”18 Between 2009 and 2015, the FSAP recorded 749 incidents in seven categories—not solely releases or researcher infections—from 276 facilities. In addition, Klotz recorded 11 confirmed releases of select agents that resulted in a laboratory-acquired infection in roughly 280 specifically approved laboratories in the United States between 2003 and 2017, a rate of just under one per year.19 A second publication in the Bulletin that covered closely-related subject matter and a personal communication from its author suggested that federally reported cases involving select agents were likely to be substantially undercounted:20 There is a fundamental problem of using the defined select agents as a surrogate for potential pandemic agent releases from research labs. The vast majority of ‘classical BW agents’ that initially defined select agents in the US were selected specifically to be NOT capable of sustained transmission so as to better define the military tactical limits of a military employment and because the establishment of progressive transmission was considered unpredictable and possibly counterproductive in military operations, at least on the US side of offensive development in the 1940s-1960s. As my historical review of lab escapes that resulted in pandemics or wide area epidemics published in the BAS found, most pandemic, continental or large scale community outbreaks originating from lab escapes came from civilian labs working with public or veterinary pathogens of non-military interest. It takes only one superspreading graduate student or maintenance worker to start a pandemic. It is known that a very large percentage of the individuals infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus show no symptoms and do not become clinically ill, which would facilitate an unrecognized infection of one or more laboratory researchers. 6. There have been laboratory accidents and escapes of highly dangerous pathogens in China in general and biosafety issues at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in particular. After the SARS epidemic in 2002-2003, which originated naturally in China and which China initially kept secret, work on the coronavirus pathogen that was responsible for the outbreak was undertaken in laboratories around the world. This research led to six cases of infection in laboratory workers: four in the National Institute of Virology in Beijing and one each in laboratories in Singapore and Taiwan. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 6, 2020 6:30:20 GMT

The laboratory-acquired infections of lab workers in Beijing led to short-lived outbreaks of SARS in the Beijing region in 2004.21

A second case of infected researchers in China resulted in brief outbreaks of disease in early December 2019. An outbreak of brucellosis began in an agricultural laboratory in Lanzhou (Gansu Province, central China) and spread to China’s premier bird flu laboratory in Harbin (Heilongjiang Province, northeast China). It was linked to index cases involving graduate students who were exposed while conducting research and included at least 96 people.22

7. Under what biosafety conditions was bat coronavirus research carried out at the Wuhan Institute of Virology? Most work—including all published work using live bat coronaviruses that were not SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV—was conducted under BSL-2 conditions.23 This was consistent with both WHO and CDC recommendations.24 BSL-2 provides only minimal protection against infection of laboratory researchers, and these regulations were almost certainly too lenient for working with bat coronaviruses. All such work should have been carried out under BSL-3 conditions. However, extremely high-risk gain of function (GoF) studies with bat SARS-related coronaviruses were carried out at BSL-3 or BSL-4. Statements made by various commentators claiming that the WIV worked only with RNA isolates and not with live viruses are untrue (as discussed in further detail in a following section).

In regard to the Wuhan Institute of Virology in particular, relevant information is again available from both Chinese and Western sources. Information from official Chinese government sources appeared in a Voice of America report which noted:

[T]here is Chinese evidence that the lab had safety problems. VOA has located state media reports showing that there were security incidents flagged by national inspections as well as reported accidents that occurred when workers were trying to catch bats for study.

About a year before the corona virus outbreak, a security review conducted by a Chinese national team found the lab did not meet national standards in five categories.

The document on the lab’s official website said after a rigorous and meticulous review, the team gave a high evaluation of the lab’s overall safety management. “At the same time, the review team also put forward further rectification opinions on the five non-conformities and two observations found during the review.”

In addition to problems in the lab, state media also reported that national reviewers found scientists were sloppy when they were handling bats.

One of the researchers working at the Wuhan Center for Disease Control & Prevention described to China’s state media that he was once attacked by bats, and he ended up getting bat blood on his skin.

In another incident, the same researcher forgot to take protective measures, and the urine of a bat dripped “like rain onto the top of his head,” reported China’s Xinhua state news agent.25

Also, information was leaked from the US Department of State and published in the Washington Post on April 14:

Two years before the novel coronavirus pandemic upended the world, U.S. Embassy officials visited a Chinese research facility in the city of Wuhan several times and sent two official warnings back to Washington about inadequate safety at the lab, which was conducting risky studies on corona viruses from bats. The cables have fueled discussions inside the U.S. government about whether this or another Wuhan lab was the source of the virus – even though conclusive proof has yet to emerge.

In January 2018, the U.S. Embassy in Beijing took the unusual step of repeatedly sending U.S. science diplomats to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which had in 2015 become China’s first laboratory to achieve the highest level of international bioresearch safety (known as BSL-4). WIV issued a news release in English about the last of these visits, which occurred on March 27, 2018. The U.S. delegation was led by Jamison Fouss, the consul general in Wuhan, and Rick Switzer, the embassy’s counselor of environment, science, technology and health. Last week, WIV erased that statement from its website, though it remains archived on the Internet.

What the U.S. officials learned during their visits concerned them so much that they dispatched two diplomatic cables categorized as Sensitive But Unclassified back to Washington. The cables warned about safety and management weaknesses at the WIV lab and proposed more attention and help. The first cable … also warns that the lab’s work on bat coronaviruses and their potential human transmission represented a risk of a new SARS-like pandemic.

“During interactions with scientists at the WIV laboratory, they noted the new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory,” states the Jan. 19, 2018, cable, which was drafted by two officials from the embassy’s environment, science and health sections who met with the WIV scientists.

“Most importantly,” the cable states, “the researchers also showed that various SARS-like coronaviruses can interact with ACE2, the human receptor identified for SARS-coronavirus. This finding strongly suggests that SARS-like coronaviruses from bats can be transmitted to humans to cause SARS-like diseases. From a public health perspective, this makes the continued surveillance of SARS-like coronaviruses in bats and study of the animal-human interface critical to future emerging coronavirus outbreak prediction and prevention.26

The US government had supplied a portion of the funds to build the Wuhan Institute of Virology and these cables were an appeal for funds to support additional training in biosafety and biosecurity. There were similar concerns about the nearby Wuhan Center for Disease Control and Prevention lab, which operates entirely at BSL-2. Chinese government authorities did not provide the US government with samples of the virus obtained from either the earliest cases or from the Wuhan fish market. A US intelligence official commented: “The idea that it was just a totally natural occurrence is circumstantial. The evidence it leaked from the lab is circumstantial. Right now, the ledger on the side of it leaking from the lab is packed with bullet points, and there’s almost nothing on the other side.”27

8. What is the nature of the research being carried out in Zhengli Shi’s laboratory at the Wuhan Institute of Virology? Details of the most recent National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant for WIV bat coronavirus surveillance and WIV bat coronavirus gain of function research are publicly available. The key activity for bat coronavirus surveillance is “Aim 1 … We will sequence receptor binding domains (spike proteins) to identify viruses with the highest potential for spillover which we will include in our experimental investigations (Aim 3).” The key activity for bat coronavirus gain of function investigation is “Aim 3…. We will use S protein sequence data, infectious clone technology, in vitro and in vivo infection experiments, and analysis of receptor binding to test the hypothesis that % divergence thresholds in S protein sequences predict spillover potential.”28

Translated into something approaching lay language, Aim 3 states that de novo synthesis is to be used to construct a series of novel chimeric viruses, comprising recombinant hybrids using different spike proteins from each of a series of unpublished natural coronaviruses in an otherwise-constant genome of a bat coronavirus. The ability of the resulting novel viruses to infect human cells in culture and to infect laboratory animals would be tested. The underlying hypothesis is that a direct correlation would be found between the receptor-binding affinity of the spike protein and the ability to infect human cells in culture and to infect laboratory animals. This hypothesis would be tested by asking whether novel viruses encoding spike proteins with the highest receptor-binding affinity have the highest ability to infect human cells in culture and laboratory animals.

The WIV began its gain of function research program for bat coronaviruses in 2015. Using a natural virus, institute researchers made “substitutions in its RNA coding to make it more transmissible. They took a piece of the original SARS virus and inserted a snippet from a SARS-like bat coronavirus, resulting in a virus that is capable of infecting human cells.”29 This meant it could be transmitted from experimental animal to experimental animal by aerosol transmission, which means that it could do the same for humans. In other words, gain of function techniques were used to turn bat coronaviruses into human pathogens capable of causing a global pandemic.

There have been three publications, in 2015,30 2016 and 2017, describing the WIV gain of function research. The WIV, having learned both basic and traceless infectious-clone technology from joint research with a laboratory at the University of North Carolina (UNC) in 2015, initiated construction of novel chimeric coronaviruses without UNC immediately thereafter. WIV’s first publication on the use of basic infectious-clone technology to construct novel chimeric coronaviruses at WIV appeared in 2016.31 WIV’s first publication on the use of traceless, signature-free infectious-clone technology also appeared in 2016.32

As this article was being edited, two excellent publications appeared that provide greater technical detail on WIV’s gain of function research, and readers should certainly examine these with care.33 The two papers strongly support the argument that the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was the results of an escape from one of the two Chinese virology laboratories in Wuhan.

The Chinese government has proudly stated that the WIV “preserves more than 1,500 strains of virus,” the largest collection in Asia of bat and other coronaviruses.34 (The government statement probably should have said 1,500 isolates rather than “strains.”) The 2019 interview with Shi in Scientific American reports that the WIV had at least hundreds of individual strains.35 These numbers have been reported by Chinese government authorities, and they are being taken at face value here.

From 2004 on, the WIV published many dozens of partial or full genome sequences of coronaviruses in their collection. On June 1, Daszak and Shi published partial genetic sequences of 781 Chinese bat coronaviruses, more than one-third of which had never been published previously.36 There are also multiple published records of animal infection research with bat coronaviruses at the WIV. In order to carry out the research program described above, the WIV laboratory needs to use live viruses, and not just RNA fragments. This contradicts two of the assertions, made by some commentators, that Shi worked only with RNA fragments and that her laboratory did not maintain live viruses. On May 24, 2020, the director of the WIV acknowledged that the laboratory did have “three live strains of bat corona viruses on site,” but implied only three.37 Knowledgeable virologists assume that the number must be much higher, probably hundreds of live viral isolates.38

It is precisely in the course of the kind of gain of function research that the WIV conducted that there would be the greatest likelihood of infection of a laboratory researcher. Many commentators have noted that millions of people in several western Chinese provinces, as well as in other South Asian countries, live their lives in daily proximity to bat caves and that serological testing has shown a fraction of these villagers to have antibodies to bat coronaviruses, showing that natural infection had occurred. The commentators argue therefore that “the odds” are in favor of SARS-CoV-2 having arisen in the field, and that a laboratory escape is so implausible that it is out of consideration. The logic of “the odds” is specious: It would take only a single laboratory infection to overcome “the odds,” if such could in fact be reckoned. That is essentially what happened in the four SARS laboratory infections that occurred in the Beijing laboratory in 2004; “the odds” for exposure of villagers in Yunnan province were irrelevant.

Since the SARS-CoV-2 genome was decoded and published, there have been numerous statements from virologists that the genome shows no indication of genetic manipulation, and that this too supports the argument that it arose in the field and did not escape from a laboratory. Although this argument implicitly recognizes that the WIV laboratory was using genetic engineering technology, there is no reason to arbitrarily assume that only a bat coronavirus that was genetically modified might have escaped from the laboratory. Nevertheless, the second portion of the NIAID research grant design made absolutely clear that the WIV would be applying genetic engineering techniques to bat coronaviruses. Using the current standard genetic engineering technology, many alterations of several bases in the RNA genome would be undetectable, including construction of a chimeric coronavirus encoding an unpublished spike protein in an unpublished genome. This would be the equivalent of a natural mutation in several bases that coded for the spike proteins.

An article in Independent Science News by Jonathan Latham and Allison Wilson discusses another mechanism, described by Nikolai Petrovsky of Flinders University in Australia, that could have resulted in the SARS-CoV-2 virus that produced the pandemic:

Take a bat coronavirus that is not infectious to humans, and force its selection by culturing it with cells that express human ACE2 receptor, such cells having been created many years ago to culture SARS coronaviruses and you can force the bat virus to adapt to infect human cells via mutations in its spike protein, which would have the effect of increasing the strength of its binding to human ACE2, and inevitably reducing the strength of its binding to bat ACE2.

Viruses in prolonged culture will also develop other random mutations that do not affect its function. The result of these experiments is a virus that is highly virulent in humans but is sufficiently different that it no longer resembles the original bat virus. Because the mutations are acquired randomly by selection there is no signature of a human gene jockey, but this is clearly a virus still created by human intervention.39

Final comments. On April 30, Newsweek described a report produced by the US Defense Intelligence Agency which stated that “in early February, China’s Academy for Military Medical Sciences ‘concluded that it was impossible for them to scientifically determine whether the Covid-19 outbreak was caused naturally or accidentally from a laboratory incident.’” The author of a newly published paper analyzing the genome of SARS-COV-2 reported that “the COVID-19 virus is exquisitely adapted to infect humans… The virus’s ability to bind protein on human cells was far greater than its ability to bind the same protein in bats, which argues against bats being a direct source of the human virus.”40

Overall, the data indicates that SARS-CoV-2 is uniquely adapted to infect humans, raising important questions as to whether it arose in nature by a rare chance event or whether its origins might lie elsewhere.

|

|