|

|

Post by Admin on May 3, 2017 19:24:55 GMT

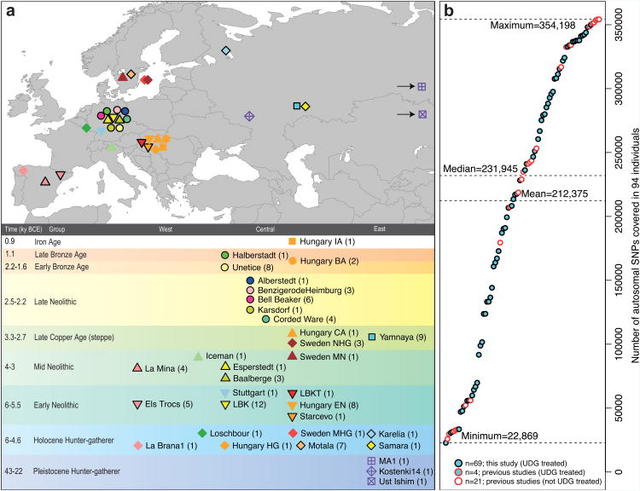

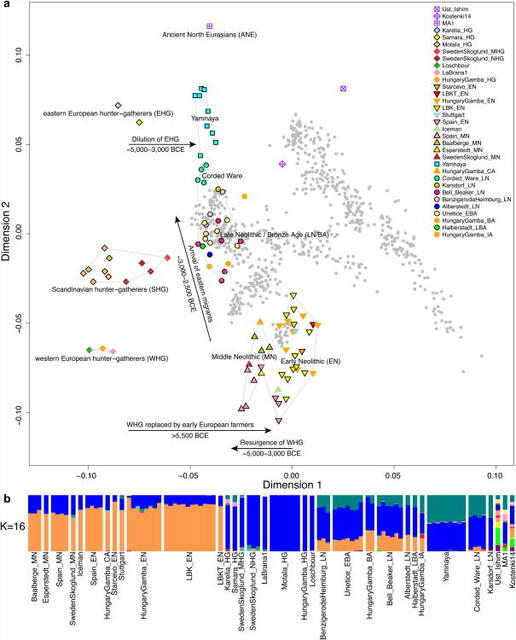

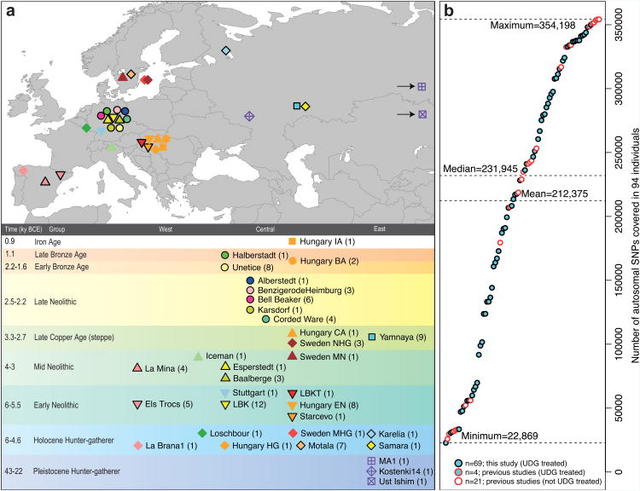

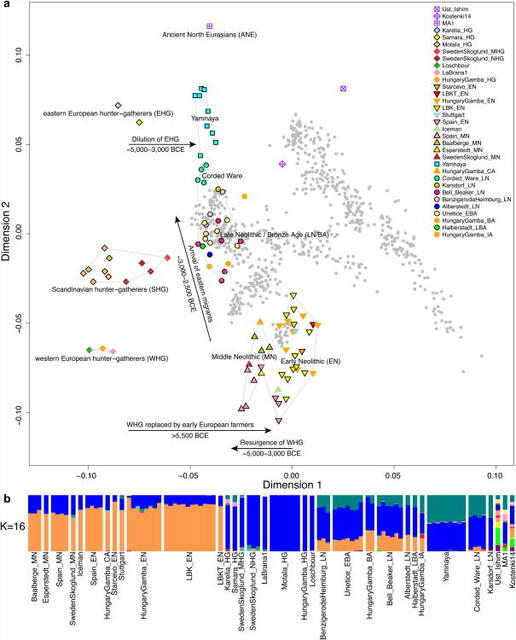

Figure 1 Location and SNP coverage of samples included in this study Outside Russia, and before the Late Neolithic period, only a single R1b individual was found (early Neolithic Spain) in the combined literature (n=70). By contrast, haplogroups R1a and R1b were found in 60% of Late Neolithic/Bronze Age Europeans outside Russia (n=10), and in 100% of the samples from European Russia from all periods (7,500–2,700 BC; n=9). R1a and R1b are the most common haplogroups in many European populations today18,19, and our results suggest that they spread into Europe from the East after 3,000 BC. Two hunter-gatherers from Russia included in our study belonged to R1a (Karelia) and R1b (Samara), the earliest documented ancient samples of either haplogroup discovered to date. These two hunter gatherers did not belong to the derived lineages M417 within R1a and M269 within R1b that are predominant in Europeans today18,19, but all 7 Yamnaya males did belong to the M269 subclade18 of haplogroup R1b. Principal components analysis (PCA) of all ancient individuals along with 777 present-day West Eurasians4 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Information section 5) replicates the positioning of present-day Europeans between the Near East and European hunter-gatherers4,20, and the clustering of early farmers from across Europe with present day Sardinians3,4, suggesting that farming expansions across the Mediterranean to Spain and via the Danubian route to Hungary and Germany descended from a common stock. By adding samples from later periods and additional locations, we also observe several new patterns. All samples from Russia have affinity to the ∼24,000-year-old MA1(ref. 6), the type specimen for the Ancient North Eurasians (ANE) who contributed to both Europeans4 and Native Americans4,6,8. The two hunter-gatherers from Russia (Karelia in the northwest of the country and Samara on the steppe near the Urals) form an ‘eastern European hunter-gatherer’ (EHG) cluster at one end of a hunter-gatherer cline across Europe; people of hunter-gatherer ancestry from Luxembourg, Spain, and Hungary sit at the opposite ‘western European hunter-gatherer’4 (WHG) end, while the hunter-gatherers from Sweden4,8 (SHG) are intermediate. Against this background of differentiated European hunter-gatherers and homogeneous early farmers, multiple population turnovers transpired in all parts of Europe included in our study. Middle Neolithic Europeans from Germany, Spain, Hungary, and Sweden from the period, ∼4,000–3,000 BC are intermediate between the earlier farmers and the WHG, suggesting an increase of WHG ancestry throughout much of Europe. By contrast, in Russia, the later Yamnaya steppe herders of ∼3,000 BC plot between the EHG and the present-day Near East/Caucasus, suggesting a decrease of EHG ancestry during the same time period. The Late Neolithic and Bronze Age samples from Germany and Hungary2 are distinct from the preceding Middle Neolithic and plot between them and the Yamnaya. This pattern is also seen in ADMIXTURE analysis (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Information section 6), which implies that the Yamnaya have ancestry from populations related to the Caucasus and South Asia that is largely absent in 38 Early or Middle Neolithic farmers but present in all 25 Late Neolithic or Bronze Age individuals. This ancestry appears in Central Europe for the first time in our series with the Corded Ware around 2,500 BC (Supplementary Information section 6, Fig. 2b). The Corded Ware shared elements of material culture with steppe groups such as the Yamnaya although whether this reflects movements of people has been contentious21. Our genetic data provide direct evidence of migration and suggest that it was relatively sudden. The Corded Ware are genetically closest to the Yamnaya ∼2,600km away, as inferred both from PCA and ADMIXTURE (Fig. 2) and FST (0.011±0.002) (Extended Data Table 3). If continuous gene flow from the east, rather than migration, had occurred, we would expect successive cultures in Europe to become increasingly differentiated from the Middle Neolithic, but instead, the Corded Ware are both the earliest and most strongly differentiated from the Middle Neolithic population. ‘Outgroup’ f3 statistics6 (Supplementary Information section 7),which measure shared genetic drift between a pair of populations (Extended Data Fig. 1), support the clustering of hunter-gatherers, Early/Middle Neolithic, and Late Neolithic/Bronze Age populations into different groups as in the PCA (Fig. 2a).We also analysed f4 statistics, which allow us to test whether pairs of populations are consistent with descent from common ancestral populations, and to assess significance using a normally distributed Z score. Early European farmers from the Early and Middle Neolithic were closely related but not identical. This is reflected in the fact that Loschbour, a WHG individual fromLuxembourg4, shared more alleles with post-4,000 BC European farmers from Germany, Spain, Hungary, Sweden and Italy than with early farmers of Germany, Spain, and Hungary, documenting an increase of hunter-gatherer ancestry in multiple regions of Europe during the course of the Neolithic.  Figure 2 Population transformations in Europe The two EHG form a clade with respect to all other present-day and ancient populations (|Z|<1.9), and MA1 shares more alleles with them (|Z|>4.7) than with other ancient or modern populations, suggesting that they may be a source for the ANE ancestry in present Europeans4,12,22 as they are geographically and temporally more proximate than Upper Paleolithic Siberians. The Yamnaya differ from the EHG by sharing fewer alleles with MA1 (|Z|=6.7) suggesting a dilution of ANE ancestry between 5,000–3,000 BC on the European steppe. This was likely due to admixture of EHG with a population related to present-day Near Easterners, as the most negative f3 statistic in the Yamnaya (giving unambiguous evidence of admixture) is observed when we model them as a mixture of EHG and present-day Near Eastern populations like Armenians (Z=-6.3); Supplementary Information section 7). The Late Neolithic/Bronze Age groups of central Europe share more alleles with Yamnaya than the Middle Neolithic populations do (|Z|=12.4) and more alleles with the Middle Neolithic than the Yamnaya do (|Z|=12.5), and have a negative f3 statistic with the Middle Neolithic and Yamnaya as references (Z=-20.7), indicating that they were descended from a mixture of the local European populations and new migrants from the east. Moreover, the Yamnaya share more alleles with the CordedWare (|Z|≥3.6) than with any other Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age group with at least two individuals (Supplementary Information section 7), indicating that they had more eastern ancestry, consistent with the PCA and ADMIXTURE patterns (Fig. 2). Modelling of the ancient samples shows that while Karelia is genetically intermediate between Loschbour and MA1, the topology that considers Karelia as a mixture of these two elements is not the only one that can fit the data (Supplementary Information section 8). To avoid biasing our inferences by fitting an incorrect model, we developed new statistical methods that are substantial extensions of a previously reported approach4, which allow us to obtain precise estimates of the proportion of mixture in later Europeans without requiring a formal model for the relationship among the ancestral populations. The method (Supplementary Information section 9) is based on the idea that if a Test population has ancestry related to reference populations Ref1, Ref2 , …, RefN in proportions α1,α2,…,αN, and the references are themselves differentially related to a triple of outgroup populations A, B, C, then: |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 4, 2017 19:43:33 GMT

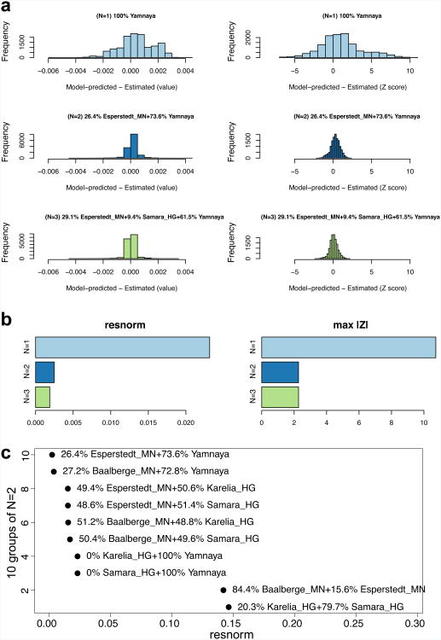

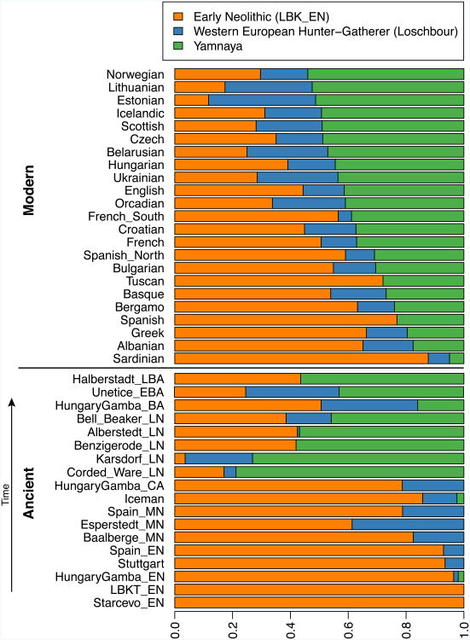

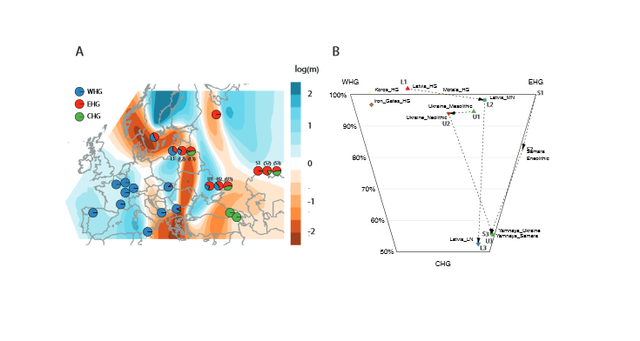

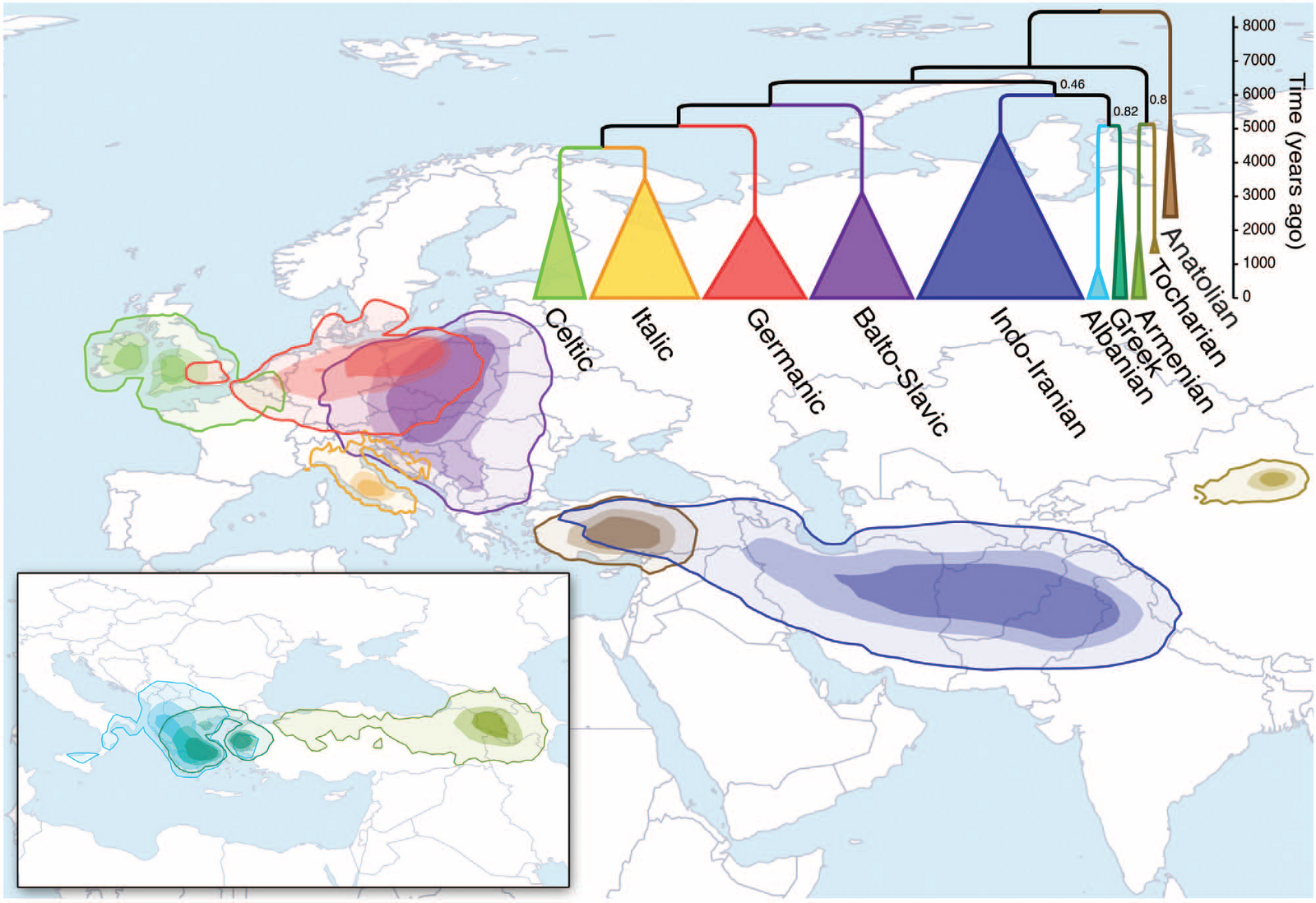

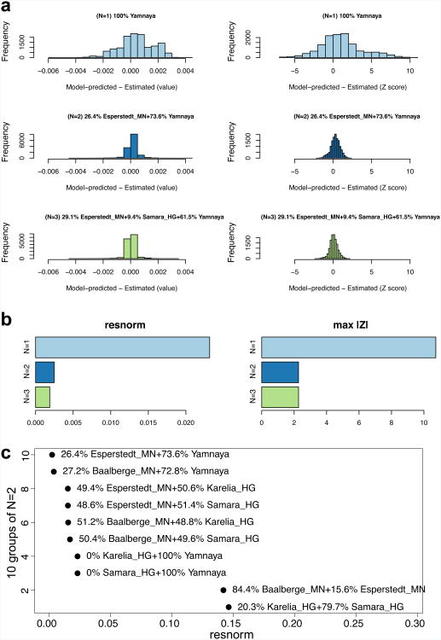

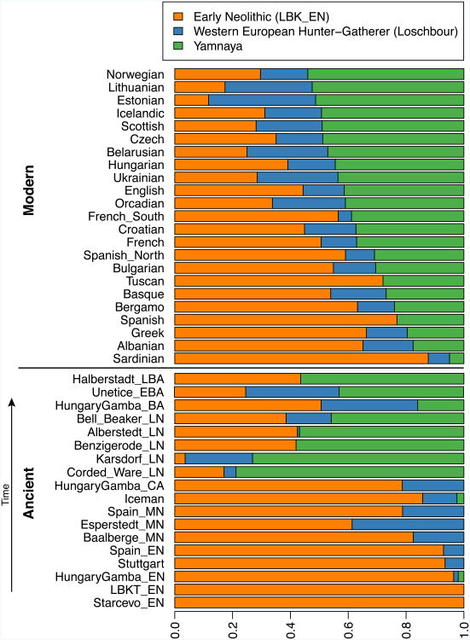

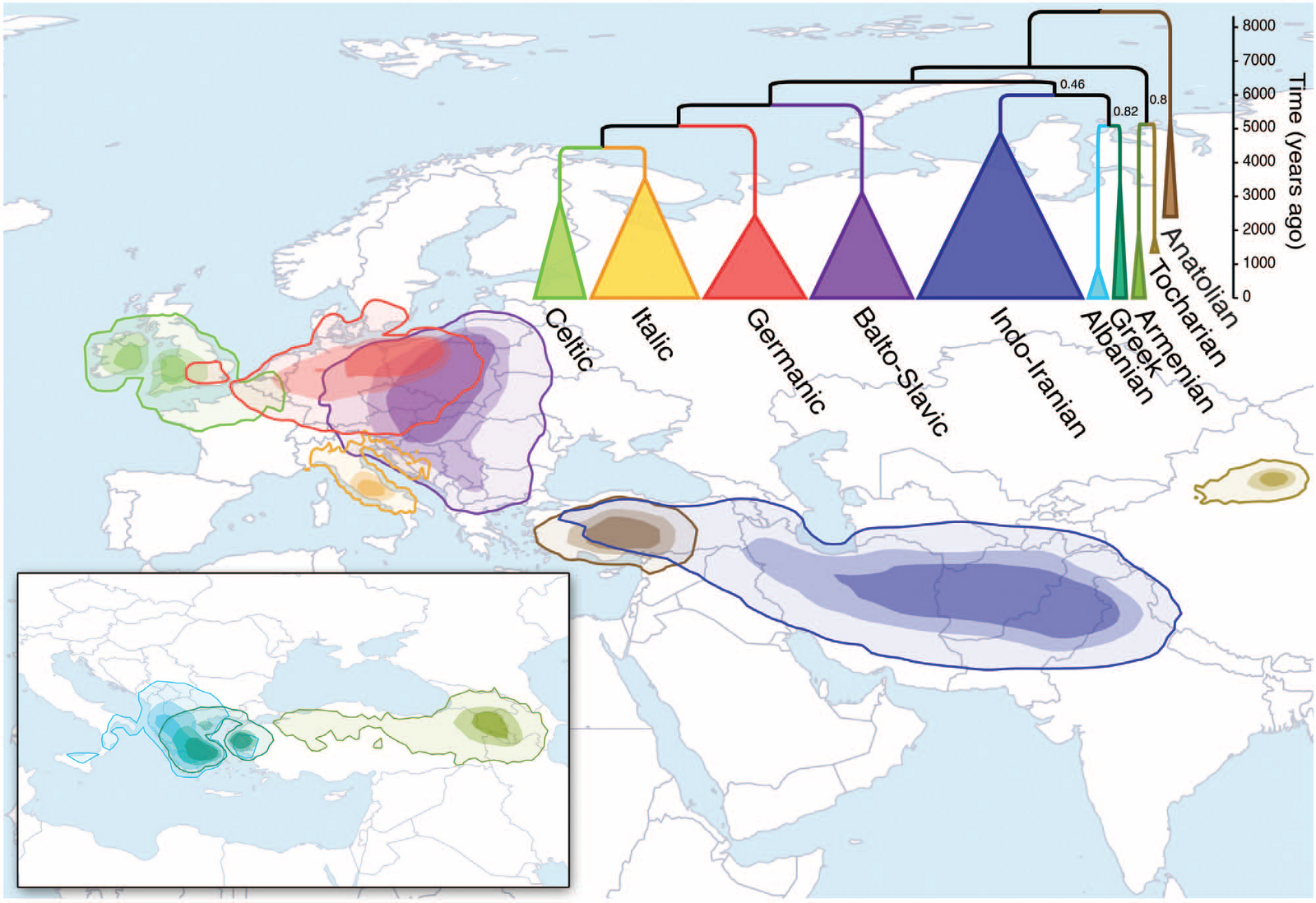

Extended Data Figure 2 By using a large number of outgroup populations we can fit the admixture coefficients αi and estimate mixture proportions (Supplementary Information section 9, Extended Data Fig. 2). Using 15 outgroups from Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas, we obtain good fits as assessed by a formal test (Supplementary Information section 10), and estimate that the Middle Neolithic populations of Germany and Spain have ∼18–34% more WHG-related ancestry than Early Neolithic populations and that the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age populations of Germany have ∼22–39% more EHG-related ancestry than the Middle Neolithic ones (Supplementary Information section 9). If we model them as mixtures of Yamnaya-related and Middle Neolithic populations, the inferred degree of population turnover is doubled to 48–80% (Supplementary Information sections 9 and 10). To distinguish whether a Yamnaya or an EHG source fits the data better, we added ancient samples as outgroups (Supplementary Information section 9). Adding any Early or Middle Neolithic farmer results in EHG-related genetic input into Late Neolithic populations being a poor fit to the data (Supplementary Information section 9); thus, Late Neolithic populations have ancestry that cannot be explained by a mixture of EHG and Middle Neolithic. When using Yamnaya instead of EHG, however, we obtain a good fit (Supplementary Information sections 9 and 10). These results can be explained if the new genetic material that arrived in Germany was a composite of two elements: EHG and a type of Near Eastern ancestry different from that which was introduced by early farmers (also suggested by PCA and ADMIXTURE; Fig. 2, Supplementary Information sections 5 and 6). We estimate that these two elements each contributed about half the ancestry of the Yamnaya (Supplementary Information sections 6 and 9), explaining why the population turnover inferred using Yamnaya as a source is about twice as high compared to the undiluted EHG. The estimate of Yamnaya related ancestry in the Corded Ware is consistent when using either present populations or ancient Europeans as outgroups (Supplementary Information sections 9 and 10), and is 73.1±2.2% when both sets are combined (Supplementary Information section 10). The best proxies for ANE ancestry in Europe4 were initially Native Americans12,22, and then the Siberian MA1 (ref. 6), but both are geographically and temporally too remote for what appears to be a recent migration into Europe4. We can now add three new pieces to the puzzle of how ANE ancestry was transmitted to Europe: first by the EHG, then the Yamnaya formed by mixture between EHG and a Near Eastern related population, and then the Corded Ware who were formed by a mixture of the Yamnaya with Middle Neolithic Europeans. We caution that the sampled Yamnaya individuals from Samara might not be directly ancestral to Corded Ware individuals from Germany. It is possible that a more western Yamnaya population, or an earlier (pre-Yamnaya) steppe population may have migrated into central Europe, and future work may uncover more missing links in the chain of transmission of steppe ancestry. By extending our model to a three-way mixture of WHG, Early Neolithic and Yamnaya, we estimate that the ancestry of the Corded Ware was 79% Yamnaya-like, 4% WHG, and 17% Early Neolithic (Fig. 3). A small contribution of the first farmers is also consistent with uniparentally inherited DNA: for example, mitochondrial DNA haplogroup N1a and Y chromosome haplogroup G2a, common in early central European farmers14,23, almost disappear during the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age, when they are largely replaced by Y haplogroups R1a and R1b (Supplementary Information section 4)and mtDNA haplogroups I,T1,U2,U4, U5a,W, and subtypes of H14,23,24 (Supplementary Information section 2). The uniparental data not only confirm a link to the steppe populations but also suggest that both sexes participated in the migrations (Supplementary Information sections 2 and 4 and Extended Data Table 2). The magnitude of the population turnover that occurred becomes even more evident if one considers the fact that the steppe migrants may well have mixed with eastern European agriculturalists on their way to central Europe. Thus, we cannot exclude a scenario in which the Corded Ware arriving in today's Germany had no ancestry at all from local populations.  Figure 3 Admixture proportions Our results support a view of European pre-history punctuated by two major migrations: first, the arrival of the first farmers during the Early Neolithic from the Near East, and second, the arrival of Yamnaya pastoralists during the Late Neolithic from the steppe. Our data further show that both migrations were followed by resurgences of the previous inhabitants: first, during the Middle Neolithic, when hunter-gatherer ancestry rose again after its Early Neolithic decline, and then between the Late Neolithic and the present, when farmer and hunter-gatherer ancestry rose after its Late Neolithic decline. This second resurgence must have started during the Late Neolithic/Bronze Age period itself, as the Bell Beaker and Unetice groups had reduced Yamnaya ancestry compared to the earlier Corded Ware, and comparable levels to that in some present-day Europeans (Fig. 3). Today, Yamnaya related ancestry is lower in southern Europe and higher in northern Europe, and all European populations can be modelled as a three-way mixture of WHG, Early Neolithic, and Yamnaya, whereas some outlier populations show evidence for additional admixture with populations from Siberia and the Near East (Extended Data Fig. 3, Supplementary Information section 9). Further data are needed to determine whether the steppe ancestry arrived in southern Europe at the time of the Late Neolithic/Bronze Age, or is due to migrations in later times from northern Europe25,26. Our results provide new data relevant to debates on the origin and expansion of Indo-European languages in Europe (Supplementary Information section 11).  Geographic distribution of archaeological cultures and graphic illustration of proposed population movements / turnovers discussed in the main text (symbols of samples are identical to Figure 1) Although the findings from ancient DNA are silent on the question of the languages spoken by preliterate populations, they do carry evidence about processes of migration which are invoked by theories on Indo-European language dispersals. Such theories make predictions about movements of people to account for the spread of languages and material culture (Extended Data Fig. 4). The technology of ancient DNA makes it possible to reject or confirm the proposed migratory movements, as well as to identify new movements that were not previously known. The best argument for the ‘Anatolian hypothesis’27 that Indo-European languages arrived in Europe from Anatolia ∼8,500 years ago is that major language replacements are thought to require major migrations, and that after the Early Neolithic when farmers established themselves in Europe, the population base was likely to have been so large that later migrations would not have made much of an impact27,28. However, our study shows that a later major turnover did occur, and that steppe migrants replaced ∼75% of the ancestry of central Europeans. An alternative theory is the ‘steppe hypothesis’, which proposes that early Indo-European speakers were pastoralists of the grasslands north of the Black and Caspian Seas, and that their languages spread into Europe after the invention of wheeled vehicles9. Our results make a compelling case for the steppe as a source of at least some of the Indo-European languages in Europe by documenting a massive migration ∼4,500 years ago associated with the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures, which are identified by proponents of the steppe hypothesis as vectors for the spread of Indo-European languages into Europe. These results challenge the Anatolian hypothesis by showing that not all Indo-European languages in Europe can plausibly derive from the first farmer migrations thousands of years earlier (Supplementary Information section 11). We caution that the location of the proto-Indo-European9,27,29,30 homeland that also gave rise to the Indo-European languages of Asia, as well as the Indo-European languages of southeastern Europe, cannot be determined from the data reported here (Supplementary Information section 11). Studying the mixture in the Yamnaya themselves, and understanding the genetic relationships among a broader set of ancient and present-day Indo- European speakers, may lead to new insight about the shared homeland. Nature. 2015 Jun 11; 522(7555): 207–211. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 16, 2017 19:31:36 GMT

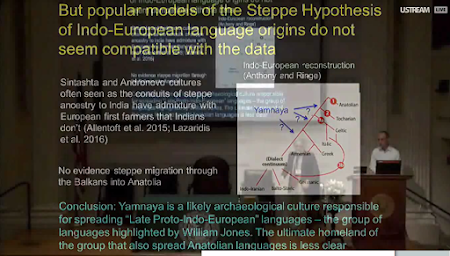

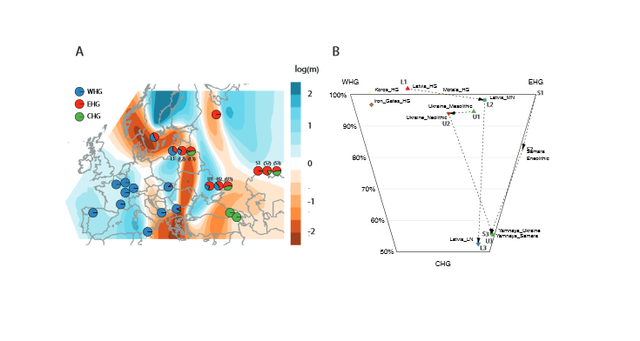

No evidence of Copper Age Balkans-to-Anatolia migration One version of the Steppe Hypothesis of Indo-European language origins suggests that Proto-Indo European languages developed in the steppe north of the Black and Caspian seas, and that the earliest known diverging branch – Anatolian – was spread into Asia Minor by movements of steppe peoples through the Balkan peninsula during the Copper Age around 4000 BCE, as part of the same incursions from the steppe that coincided with the decline of the tell settlements.  Figure 1: Geographic locations and genetic structure of newly reported individuals. If this were correct, then one way to detect evidence of it would be the appearance of large amounts of characteristics teppe ancestry first in the Balkan Peninsula and then in Anatolia. However, our genetic data do not support this scenario. While we find steppe ancestry in Balkan Copper Age and Bronze Age individuals, this ancestry is sporadic across individuals in the Copper Age, and at low levels in the Bronze Age. Moreover, while Bronze Age Anatolian individuals have CHG / Iran Neolithic related ancestry, they have neither the EHG ancestry characteristic of all steppe populations sampled to date, nor the WHG ancestry that is ubiquitous in southeastern Europe in the Neolithic (Figure 1A, Supplementary Data Table 2, Supplementary Information section 1). This pattern is consistent with that seen in northwestern Anatolia and later in Copper Age Anatolia, suggesting continuing migration into Anatolia from the East rather than from Europe. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 18, 2017 19:19:49 GMT

Figure 2; Structure and population change in European populations with mainly hunter-gatherer ancestry. An alternative hypothesis is that the ultimate homeland of Proto-Indo European languages was in the Caucasus or in Iran. In this scenario, westward movement contributed to the dispersal of Anatolian languages, and northward movement and mixture with EHG was responsible for the formation of the population associated with the Yamnaya complex. These steppe pastoralists plausibly spoke a “Late Proto-Indo European” language that is ancestral to many of the non-Anatolian branches of the Indo-European language family.  On the other hand, our data could still be consistent with the Steppe-Balkans-Anatolia route hypothesis model, albeit with constraints. It remains possible that populations dating to around 1600 BCE in the regions where the Indo-European Luwian, Hittite and Palaic languages were spoken did have European hunter-gatherer ancestry. However, our results would require that such ancestry was not ubiquitous in Bronze Age Anatolia, and was perhaps tightly linked to Indo-European speaking groups.  We predict that additional insight about the genetic origins of the potential speakers of early Indo-European languages will be obtained when ancient DNA data become available from additional sites in this key period in Anatolia and the Caucasus. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 15, 2017 19:53:32 GMT

Ever since the days of Homer, Greeks have long idealized their Mycenaean “ancestors” in epic poems and classic tragedies that glorify the exploits of Odysseus, King Agamemnon, and other heroes who went in and out of favor with the Greek gods. Although these Mycenaeans were fictitious, scholars have debated whether today’s Greeks descend from the actual Mycenaeans, who created a famous civilization that dominated mainland Greece and the Aegean Sea from about 1600 B.C.E. to 1200 B.C.E., or whether the ancient Mycenaeans simply vanished from the region.  Now, ancient DNA suggests that living Greeks are indeed the descendants of Mycenaeans, with only a small proportion of DNA from later migrations to Greece. And the Mycenaeans themselves were closely related to the earlier Minoans, the study reveals, another great civilization that flourished on the island of Crete from 2600 B.C.E. to 1400 B.C.E. (named for the mythical King Minos).  The ancient DNA comes from the teeth of 19 people, including 10 Minoans from Crete dating to 2900 B.C.E. to 1700 BCE, four Mycenaeans from the archaeological site at Mycenae and other cemeteries on the Greek mainland dating from 1700 B.C.E. to 1200 B.C.E., and five people from other early farming or Bronze Age (5400 B.C.E. to 1340 B.C.E.) cultures in Greece and Turkey. By comparing 1.2 million letters of genetic code across these genomes to those of 334 other ancient people from around the world and 30 modern Greeks, the researchers were able to plot how the individuals were related to each other. The ancient Mycenaeans and Minoans were most closely related to each other, and they both got three-quarters of their DNA from early farmers who lived in Greece and southwestern Anatolia, which is now part of Turkey, the team reports today in Nature. Both cultures additionally inherited DNA from people from the eastern Caucasus, near modern-day Iran, suggesting an early migration of people from the east after the early farmers settled there but before Mycenaeans split from Minoans.  The Mycenaeans did have an important difference: They had some DNA—4% to 16%—from northern ancestors who came from Eastern Europe or Siberia. This suggests that a second wave of people from the Eurasian steppe came to mainland Greece by way of Eastern Europe or Armenia, but didn’t reach Crete, says Iosif Lazaridis, a population geneticist at Harvard University who co-led the study.  While both Minoans and Mycenaeans had both "first farmer" and "eastern" genetic origins, Mycenaeans traced an additional minor component of their ancestry to ancient inhabitants of Eastern Europe and northern Eurasia. This type of so-called Ancient North Eurasian ancestry is one of the three ancestral populations of present-day Europeans, and is also found in modern Greeks. In broad strokes, the new study shows that there was genetic continuity in the Aegean from the time of the first farmers to present-day Greece, but not in isolation. The peoples of the Greek mainland had some admixture with Ancient North Eurasians and peoples of the Eastern European steppe both before and after the time of the Minoans and Mycenaeans, which may provide the missing link between Greek speakers and their linguistic relatives elsewhere in Europe and Asia. |

|