|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 6, 2014 6:06:24 GMT

Anniversaries are useful moments to pause and reflect. For the 70th anniversary of D-Day and subsequent campaign in northern France, it is also an opportunity to look at the past in detail and ask how much of what we think we know is true and how much is well-entrenched myth. Not only is it more interesting, it is also of greater worth as we plan for the future and pray there will never be a conflict like World War II again. 1. MYTH: D-Day was predominantly an American operationREALITY: For many people, D-Day is defined by the bloodshed at Omaha -- the codename for one of the five beaches where Allied forces landed -- and the American airborne drops. Even in Germany, the perception is still that D-Day was a largely American show; in the recent German TV mini-series, "Generation War," there was a reference to the "American landings" in France.  But despite "Band of Brothers," despite "Saving Private Ryan," despite those 11 photographs taken by Robert Capa in the swell on that morning of June 6 1944, D-Day was not a predominantly American effort. Rather, it was an Allied effort with, if anything, Britain taking the lead. Yes, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, was American, but his deputy, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder was British, as were all three service chiefs. Air Marshal Sir Arthur "Mary" Coningham, commander of the tactical air forces, was also British. The plan for Operation Overlord -- as D-Day was codenamed -- was largely that of Gen. Bernard Montgomery, the land force commander. The Royal Navy had overall responsibility for Operation Neptune, the naval plan. Of the 1,213 warships involved, 200 were American and 892 were British; of the 4,126 landing craft involved, 805 were American and 3,261 were British. Indeed, 31% of all U.S. supplies used during D-Day came directly from Britain, while two-thirds of the 12,000 aircraft involved were also British, as were two-thirds of those that landed in occupied France. Despite the initial slaughter at Omaha, casualties across the American and British beaches were much the same. This is not to belittle the U.S. effort but rather to add context and a wider, 360-degree view. History needs to teach as well as entertain. 2. MYTH: American forces were ill-preparedREALITY: By the end of World War II the United States had the best armed services in the world. The 77-day Normandy campaign did much to help them reach this point. Northern France was a showcase for American tactical and operational flexibility. At the start of the campaign, the Americans found themselves fighting through the Norman "bocage," an area of small fields lined with thick, raised hedgerows and narrow, sunken lanes. They hadn't trained for this; instead they expected that the Germans would quickly retreat after a successful Allied landing. For the Germans, the bocage offered cover and ambush opportunities for mortar teams and machine guns. Even the American 30-ton Sherman tanks couldn't get through these hedgerows. Then a U.S. sergeant came up with the ingenious solution of attaching a hedge-cutting tool built from German beach obstacles to the front of a Sherman. Gen. Omar Bradley, the U.S. First Army commander, was impressed; within a fortnight, the device had been fitted to 60% of all U.S. Shermans in Normandy. This was but one example. During the campaign huge developments also were made in close air support, as well as in coordination between infantry, artillery and armor. Medical services advanced so much that one in four casualties returned to the battlefield after treatment, remarkable for 1944. The dogged determination of the Germans to fight during D-Day is often confused with tactical skill. 3. MYTH: The Allies became bogged down in NormandyREALITY: In the pre-invasion estimates for the Normandy campaign, the Allies expected to be roughly 50 miles inland after 17 days, based on German retreats in North Africa and Italy. But Adolf Hitler ordered his forces to fight as close to the French coast as possible and not give an inch. On paper it seemed that the Allies weren't making much progress, but in reality the German strategy worked to the Allies' advantage as they pounded the enemy with offshore naval guns. For by 1944 the Allies had realized that German tactics -- which dated back more than 100 years -- were rigidly predictable. Striking back once the enemy had overextended itself was central to German DNA throughout World War II. The Allies soon realized that this penchant for counterattack meant that the Germans would eventually move into the open and get hammered. By the end of the Normandy campaign the Germans were hemorrhaging men and machines, with two armies all but destroyed. True, a handful of Germans did escape the attempted encirclement around Falaise, but it was still a massive Allied victory. In the rapid advance that followed, the Allies moved more quickly than Germans had in the opposite direction four years before, during the invasion of France. 4. MYTH: German soldiers were better trained than their Allied counterpartsREALITY: At the start of World War II the best German units were more than a match for their Allied opposition -- but by 1944 that had changed radically. There were a few exceptions, such as the Panzer Lehr, but come D-Day most German units were not as well trained as the Allies.Some Allied units in Normandy had been preparing for four years for this campaign. In contrast, many German troops had had little more than a few weeks' notice. The German ad hoc battle groups known as kampfgruppen are traditionally regarded as showcasing tactical flexibility, but even these were borne of extreme shortages and desperation toward the end of the war. The German paratroopers, or fallschirmjäger, were acknowledged to be among the best of their armed forces, yet one veteran I interviewed recalled how he had barely any training, save a few route marches and practice at laying mines. He never trained with a tank, had no transport and had to march 200 miles from Brittany when sent to the front. His case was not atypical: All infantry divisions in Normandy were expected to move by either foot or horse-drawn cart. The veteran I spoke to reached Saint-Lô, a major Normandy town, on June 12 with a company of 120 men. When he was captured on August 19 he was one of just nine men still standing. The Germans had a doctrine during World War II called auftragstaktik -- best described as the ability to use one's initiative -- which has been hailed as what set their soldiers apart. But the paratrooper I spoke to knew nothing of it. By that stage of the war, German training was so skimpy that it was impossible to implement. Even in Germany, the perception is still that D-Day was a largely American show James Holland  5. MYTH: The Germans had stronger tactical skills 5. MYTH: The Germans had stronger tactical skillsREALITY: The dogged determination of the Germans to fight during D-Day is often confused with tactical skill. It shouldn't. The best analogy is with more recent conflicts like Afghanistan or even Vietnam, when Western forces had the best training and kit yet struggled to defeat a massively inferior enemy. As the Taliban have shown, it is very difficult to completely defeat your enemy if they don't want to be defeated. The only way to do that is to kill them all. This is why the Germans took so long to be defeated in Normandy and, subsequently, despite a lack of training, they were still a very dangerous and deadly enemy with plenty of powerful weapons and a fierce determination to keep fighting. This was for a number of reasons: Nazi indoctrination, a profound sense of duty and the threat of execution for deserters. In World War I the Germans executed 48 men for desertion; during World War II that figure rose to 30,000. 6. MYTH: America and Britain got off lightly in World War IIREALITY: Allied frontline troops suffered horrifically during World War II. Democracies such as Britain and America tried to achieve victory with as few casualties as possible. For the most part, they did this very successfully using technology and machinery to shield lives wherever they could. However, short distances still had to be won by the infantry, tank units and artillery. Although technology meant the Allies needed fewer forces than a generation earlier, those in the firing line still pulled the very short straw. Losses to frontline troops were proportionally worse during the 77-day Normandy campaign than they were during the major battles along the Western Front during World War I. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 7, 2014 6:09:20 GMT

Seventy years ago today, the biggest military operation in history took place, as thousands of Allied troops landed on the French coast. Below are extracts from the BBC's reports of D-Day. The first part of D-Day involved the dropping of 24,000 British, Canadian and US troops in Nazi-occupied France, shortly after midnight. In this audio clip, and in the script below, Richard Dimbleby, the BBC's war correspondent and one of its most famous journalists, witnessed the very first aircraft take off from southern England on the night of 5 June 1944.  BBC war correspondent Robert Barr was one of four reporters who followed General Dwight Eisenhower from D-Day until the end of World War Two. Here, he records the anticipation as paratroopers prepare to board a Douglas C-47 destined for France.  Allied infantry started to land on the Normandy coast at 06:30. At 08:00, the BBC announced that "a new phase of the Allied Air Initiative has begun". At midday, the radio announcer John Snagge was able to go further and announced that "D-Day has come". The dispatch below, filed by Robert Dunner from an American headquarters ship, described the atmosphere as troops waited to land in France.  The invasion of Normandy was the largest amphibious assault ever launched. It involved five army divisions in the initial assault and over 7,000 ships. In addition there were 11,000 aircraft. Colin Wills painted the scene from above, in a plane flying over the English channel. Below, the veteran BBC reporter Howard Marshall described the moment when one boat of troops landed.  On 6 June, 1944, British, US and Canadian forces invaded the coast of northern France at Normandy. The landings were the first stage of Operation Overlord - the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe, and were intended to bring World War Two to an end. The invasion of Normandy was the largest amphibious assault ever launched. Over 150,000 troops landed on D-Day. By the end of D-Day, the allies had established a foothold in France. Within 11 months Nazi Germany was defeated.  |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 14, 2014 0:09:48 GMT

Inclusion of the Senkakus (Diaoyu Islands) in the Okinawa Reversion Treaty Inclusion of the Senkakus (Diaoyu Islands) in the Okinawa Reversion Treaty The Okinawa Reversion Treaty,15 which was signed on June 17, 1971, and entered into force onMay 15, 1972, provided for the return to Japan of “all and any powers of administration,legislation and jurisdiction” over the Ryukyu and Daito islands, which the United States had heldunder the Japan Peace Treaty. Article I of the Okinawa Reversion Treaty defines the term “theRyukyu Islands and the Daito Islands” as “all territories with their territorial waters with respectto which the right to exercise all and any powers of administration, legislation and jurisdictionwas accorded to the United States of America under Article 3 of the Treaty of Peace with Japan....” An Agreed Minute to the Okinawa Reversion Treaty defines the boundaries of the RyukyuIslands and the Daito islands “as designated under” USCAR 27. Moreover, the latitude andlongitude boundaries set forth in the Agreed Minute appear to include the Senkakus(Diaoyu/Diaoyutai). A letter of October 20, 1971, by Robert Starr, Acting Assistant Legal Adviserfor East Asian and Pacific Affairs—acting on the instructions of Secretary of State WilliamRogers—states that the Okinawa Reversion Treaty contained “the terms and conditions for thereversion of the Ryukyu Islands, including the Senkakus.”  U.S. Position on the Competing Claims U.S. Position on the Competing Claims During Senate deliberations on whether to consent to the ratification of the Okinawa ReversionTreaty, the State Department asserted that the United States took a neutral position with regard tothe competing claims of Japan, China, and Taiwan, despite the return of the islets to Japaneseadministration. Department officials asserted that reversion of administrative rights to Japan didnot prejudice any claims to the islets. When asked by the chairman of the Senate ForeignRelations Committee how the Okinawa Reversion Treaty would affect the determination of sovereignty over the Senkakus (Diaoyu/Diaoyutai), Secretary of State William Rogers answered that “this treaty does not affect the legal status of those islands at all.”17 In his letter of Octobe r20, 1971, Acting Assistant Legal Adviser Robert Starr stated: Successive U.S. administrations have restated this position of neutrality regarding the claims,particularly during periods when tensions over the islets have flared, as in 1996, 2010, and 2012.  The U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and the Islets The U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and the Islets The inclusion of the Senkakus (Diaoyu Islands) in the Okinawa Reversion Treaty under thedefinition of “the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands” made Article II of the Treaty applicableto the islets. Article II states that “treaties, conventions and other agreements concluded between Japan and the United States of America, including, but without limitation to the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States of America ... become applicable to the Ryukyu Islands and the Daito Islands as of the date of entry into force of this Agreement.”19 Using “Okinawa” as shorthand for the territory covered by the Treaty, Secretary of State Rogers stated in his testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the Security Treaty“becomes applicable to Okinawa” in the same way as it applied to the Japanese home islands.20 Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard, in his testimony, stressed that Japan would assume the “primary responsibility” for the defense of the treaty area but that the Security Treaty was applicable.21 In short, while maintaining neutrality on the competing claims, the United States agreed in the Okinawa Reversion Treaty to apply the Security Treaty to the treaty area, including the Senkaku(Diaoyu/Diaoyutai). During a 2010 worsening of Japan-PRC relations over the islets, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton summed up the U.S. stance by stating, “... with respect to the Senkaku Islands, the United States has never taken a position on sovereignty, but we have mad It also should be noted that in providing its consent to U.S. ratification of the Treaty, the Senate did not act on the advice of several committee witnesses that it include a reservation concerning the Senkakus (Diaoyu/Diaoyutai) in the resolution of advice and consent to ratification.Moreover, the Security Treaty itself declares in Article V that each party would act “in accordance with its constitutional provisions and processes”23 in response to “an armed attack ... in the territories under the administration of Japan.” “Administration” rather than “sovereignty” is the key distinction that applies to the islets. Since 1971, the United States and Japan have not altered the application of the Security Treaty to the islets. China’s increase in patrols around the Senkakus since the fall of 2012 appears to many to be an attempt to demonstrate that Beijing has a degree of administrative control over the islets, thereby exploiting the U.S. distinction between sovereignty and administrative control. Some observers,seeking to avoid a situation where the United States inadvertently encourages more assertive Chinese actions, have called on Obama Administration officials to stop using the word “neutral”in describing the U.S. position on the issue and to also publicly declare that unilateral actions by China (or Taiwan) will not affect the U.S. judgment that the islets are controlled by Japan. In its own attempt to address this perceived gap, Congress inserted in the FY2013 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4310, P.L. 112-239) a resolution stating, among other items, that “the unilateral action of a third party will not affect the United States’ acknowledgment of the administration of Japan over the Senkaku Islands.” Perhaps responding to the criticism of the Administration’s rhetoric, in January 2013 Secretary Hillary Rodham Clinton stated that “we oppose any unilateral actions that would seek to undermine Japanese administration” of the islets during opening remarks to the press with Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida. Senkaku (Diaoyu/Diaoyutai) Islands Dispute: U.S. Treaty Obligations. Publisher, United States Congressional Research Service. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 24, 2014 22:56:04 GMT

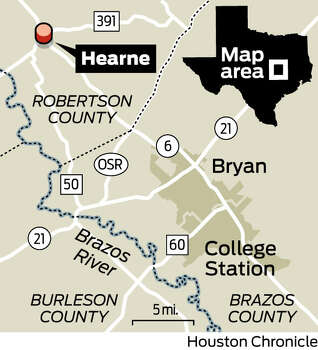

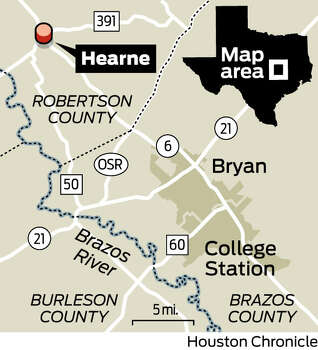

In the quiet little Central Texas community of Hearne, a huge part of forgotten Texas history is on public display. More than a decade ago, Texas A&M University professor Michael Waters, along with more than 300 graduate and undergraduate anthropology students, unearthed more than 1,400 artifacts from one of the 70 prisoner-of-war camps established in Texas during World War II. And now, the Camp Hearne exhibit and visitors center, opened to the public in 2010, houses many of those invaluable pieces of history as it tells the story of what life was like in the German POW camp. In 1942, hoping to secure economic prosperity for their agricultural community of 3,500, the civic leaders of Hearne lobbied for the construction of the POW camp. Waters details in his book Lone Star Stalag: German Prisoners of War At Camp Hearne (Texas A&M University Press, 2004) why Hearne fit the criteria for an ideal camp location: It was in a rural setting far from crucial war industries; it was not within the coastal blackout zone (which extended 170 miles inland from the coast); and it was more than 150 miles from the Mexican border. Fascinatingly, Texas had about twice as many POW camps as any other state because of ample space and climate: The 1929 Geneva Conventions required that prisoners of war be moved to a climate similar to that of where they were captured. It was thought that Texas’ weather conditions resembled those of North Africa, where some German POWs surrendered.  The Germans had it pretty good at what Hearne residents then described as the "Fritz Ritz." By the middle of World War II, Great Britain no longer had enough space, or enough food, to house and feed prisoners, and American Liberty ships that transported troops and supplies to Europe and Africa had empty holds for the return trips home. So the Allies decided to fill those holds with Germans. The U.S. Army sought to abide by the Geneva Convention, so non-commissioned officers and those of higher rank didn't have to work. The American Red Cross provided them with implements and tools, and the prisoners built fountains and statues, made woodcarvings, played soccer and staged concerts and plays. They could go to classes and learn English.  They made their move in August. After less than three days of summer heat and portaging their rafts over gravel bars in the low-water Brazos, the sunburned escapees were caught less than a dozen miles away, Waters said. The biggest tension was between the true believer Nazis and those who didn't share their faith in Hitler. These ill feelings came to a head in late 1943, when the Nazi faction beat to death a prisoner sympathetic to the United States. But overall, life was pretty good in the camp. Workers received compensation for their labor, and all prisoners got coupons to spend at the post exchange. They also got tickets for a beer a day.  Prisoners enjoyed sports on recreation fields. Non-commissioned officers and those of higher rank were not required to work. Soccer was a popular pasttime. Work details at Hearne became harder. Daily food rations were dropped from about 2,000 calories a day to about 1,200 calories, Lazarus said. German prisoners were forced to look at films Americans were making of POW camps in the fatherland. After the war ended, the German prisoners were kept a few months, through the 1945 harvest. Then they were sent back to New York, then on to Europe, and by the late 1940s, to Germany. Some, like Erichsen, were eager to return to America as free men. For some captives, the beacon of democracy proved strong indeed. Erichsen's story, and those of others, are now being retold in this small town in a state where many have forgotten the camp once existed, and most never knew it did. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jul 28, 2014 22:52:01 GMT

It’s a cold May morning at 6,000 feet in the Eastern Alps. Knee-deep in icy snow just below the summit of Mount Čukla, lost in the fog and clinging to wet rocks, I am standing on the site of one of the most brutal battles of World War I, 100 years after the war to end all wars began. My great-grandfather never made it this far up the mountain. Sergeant Amatore Archetti of the Italian Army's 5th Alpine Regiment was killed in action just south of here on May 11, 1916, the day his comrades took the summit back from the Austrians. He was one of the 10 million soldiers who died in the war that began a century ago, on July 28, 1914. His brother-in-law, artillery Corporal Giovanni Maria Rottigni, died the following October, hit by an Austrian shell in a trench 50 miles to the south.  Now, a century later, I am here chasing their memory, and the remains of a history that Italy has largely rejected. The country hasn't quite come to grips with the legacy of the only major war it ever won. Hijacked by fascism and turned into an avatar of aggressive nationalism—a young Benito Mussolini fought on this very mountain, noting the bitter cold of Čukla prominently in his diary—the Great War was an unmentionable for decades. It was the deadliest Italian war, killing twice the number of soldiers that World War II did, yet its nationalistic overtones made it into a near-taboo subject to many Italians rather than a hallowed memory. My family rarely talked about the great-grandfather who died in that war. His children—my grandmother and great-uncle—never made it to the war memorial where he rests, never even knew where it was, until decades later, when my father tracked it down. My great-grandmother Bettina, who had lost a husband as well as a brother, died before I was old enough to ask her about those years.  Yet today, spurred by the hundredth anniversary, talk of La Grande Guerra is finally permissible. "The memory is returning, in a major way," says Paolo Rumiz, an Italian author and journalist who has written extensively about the Great War. His grandfather fought on the other side, with the Austrians—not an uncommon occurrence in this part of the world, where families changed nationalities more than once as Italy, Austria and Yugoslavia grabbed chunks of this corner of Europe. The Italian language has an expression, it was a Caporetto, to indicate a devastating defeat. Caporetto is a hamlet here, just south of Čukla, where the Italian army was routed in late 1917 before regrouping to win the war one year later. Now a Slovenian town called Kobarid, it houses an Italian war memorial with the remains of 7,000 soldiers, great-grandfather Amatore among them.  His grandson Franco, my father Silvio and I tread carefully up the mountain. We are all experienced climbers, but the barbed wire that stopped assaults a century ago is still there, rusted but just as dangerous to distracted hikers. Tin cans that long ago held field rations rest among the stones. Overhead, circling vultures remind the visitor that death once ruled this mountain. Far below in the town of Bovec, its tools are everywhere, below the pretty surface of an idyllic resort. Our innkeeper shows us the exploded shells and intact bullet clips he’s found in his garden. His neighbor, he says, had to call in the army when he found seven live grenades while digging up his yard.  Europe has come a long way since the fighting on Čukla. It’s a peaceful union of 500 million people that doesn’t even demand to see passports at its borders; on the frontier where our ancestors fought ferociously for every inch of ground, we breezed through from Italy with nary a wave from the Slovenian guards. That border used to be the Cold War's front line, too: Yugoslav Communists east of the barbed wire, Italy and NATO west, on a frontier that had seen war since Attila the Hun came this way with his sights on Rome. Driving down the Isonzo to the Adriatic Sea today, one gets the feeling that the unrest brewing east of the river could make its way to this border easily.  The headlines in the Slovenian and Italian newspapers talked about the upcoming elections for the European Union's parliament, in which bellicose right-wing xenophobes would do well across the continent. The civil war in Ukraine echoes loudly here: It's happening just across the plains of central Europe, near the old border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that died with the Great War. "We are sleepwalking, like they were in 1914. They just don't understand," says Rumiz of Europe's current leaders, when we meet in a coffee shop in Trieste, the empire's port city. Italy captured it in 1918, lost it again after World War II, and gained it back in 1954. Few other cities bear such powerful witness to the madness of Europe's 20th century.  "The Balkans, Ukraine, North Africa, Catalonia… These conflicts are on the same fault lines of 1914," says Rumiz, reeling off a list of everything that's going wrong in and around the prosperous, but crisis-plagued, area. Yet the leadership in Brussels is ignoring the war's centenary "because it's afraid. They know they aren't really united, but rather susceptible nations." Rumiz has written extensively on the wars next door to Trieste, in the former Yugoslavia. The bones of the dead he saw at Srebrenica in Bosnia remind him, he says, of the Italian and Austrian soldiers' bones that sometimes still surface near here. He is just back from traveling along the front lines of World War I, chronicling its legacy for Italian newspaper la Repubblica, and the message he took back is not encouraging: "Peace is not written into our DNA." But in the quiet of a spring afternoon, finding my great-grandfather's name etched in the stone of the Kobarid memorial did not evoke warlike feelings. At the entrance to the mausoleum, a sign placed by the Slovenians, themselves a nation produced by civil war, featured an elegant logo with a stylized white dove. Signs like it appear all along the trails once trod by soldiers' boots. The stories they tell are impossibly bloody, but the Slovenian name they bear says something else: Pot miru, the path of peace. |

|