Post by Admin on Oct 10, 2019 23:06:40 GMT

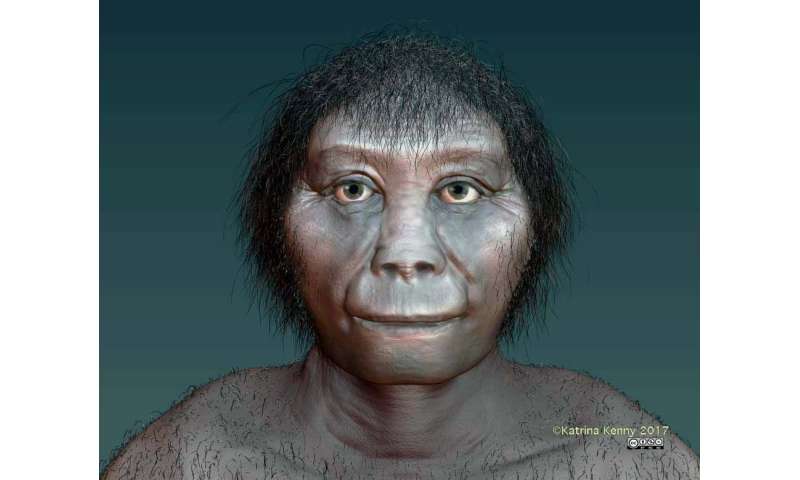

The Days of Hobbits

The H. floresiensis fossils were found in Liang Bua cave on Flores, a narrow island — about 200 miles long and 40 miles wide — between Southeast Asia and Australia. Initially, researchers reported that the remains dated between 12,000 and 95,000 years old. For an extinct human species, 12,000 years ago is crazy recent — modern humans were building permanent settlements and monuments by then.

It turns out, the sensational dates were wrong. Continued excavations and analysis showed the hobbit fossils derive from sediment layers between 60,000 and 100,000 years old. And artifacts likely made by H. floresiensis extend between 50,000 and 190,000 years ago, suggesting the species was there even further back, even if we haven’t found their bones.

The thought of hobbits persisting until at least 50,000 years ago is nevertheless exciting. They very well could have encountered our own species, Homo sapiens, thought to have reached Australia by 65,000 years ago. Perhaps modern humans, migrating Down Under, met (and maybe killed) hobbits along the way.

A 2016 Nature paper described hobbit-like fossils at Mata Menge, also on Flores, about 45 miles from Liang Bua. The finds included stone tools, a lower-jaw fragment and six tiny teeth, dated to approximately 700,000 years ago — substantially older than the Liang Bua fossils. Although the Mata Menge remains are too scanty to definitively assign them to the species, most anthropologists consider them hobbits.

At a third Flores site, researchers found no human fossils, but uncovered 1 million-year-old stone tools, like those from Liang Bua and Mata Menge. Assuming these artifacts were made by H. floresiensis or its ancestors, the hobbit lineage inhabited Flores at least from 50,000 to 1 million years ago. That’s over a half million years longer than our species has even existed.

Figure 1: SOA-MM4 mandible compared with a Liang Bua H. floresiensis specimen.

Unearthing Little Humans

Digging in Liang Bua since 2001, an international team has uncovered bones from about a dozen hobbits. But the star specimen is called LB1. It’s the most complete individual, comprising a skull, partial pelvis and bones from the limbs, hands and feet. LB1 appears to be a female adult (her wisdom teeth are fully formed), but measured just 3 foot 6 inches tall and weighed 75 pounds — as tall as a present day 4-year-old, but heftier.

Using micro-CT scanning (high resolution 3D X-ray imaging), a 2013 study estimated her brain volume to be about 426 cc (~1.8 cups). Similarly sized brains are characteristic of much earlier human ancestors, such as Australopiths who lived in Africa some 3 million years ago. The global average for modern humans is ~1,350 cc (5.7 cups), over 3 times larger.

Besides their wee bodies and brains, hobbit skeletons show a mix of primitive and modern-looking traits. Like Australopiths and other early hominins, LB1 has ancient features including broad hips, a short collarbone and forward-positioned shoulder. At the same time, the hobbits’ brow ridges, skull thickness and brain shape are more modern, resembling H. erectus and later species.

The Liang Bua team has also dug up more than 20,000 stone tools. Most are made from volcanic rocks, deliberately fractured to have sharp edges for slicing and dicing. This simple technology resembles the earliest widespread style of toolmaking, the Oldowan, made by numerous ancestral species, starting in Africa 2.6 million years ago.

Figure 2: Isolated teeth from Mata Menge.

The Million-Dollar Questions

Big questions persist about the little creatures: Where do they fit in the human evolutionary tree and why did they go extinct?

Anthropologists have put forth three main hypotheses for the hobbits’ evolutionary origins. One idea, which now lacks support, was that the population belonged to our species, Homo sapiens, but suffered from a genetic or metabolic disorder, responsible for their unusual features. Proponents suggested conditions like microcephaly and Down syndrome, but most scientists conclude the physical symptoms of these disorders are not reflected in H. floresiensis‘ skeletal traits. Furthermore, the 700,000-year-old Mata Menge fossils indicate the hobbits were a long-lived lineage, rather than an isolated, diseased community.

That leaves two hypotheses standing: The hobbits were dwarfed H. erectus — taller, brainier ancestors who appeared ~1.8 million years ago — or the descendants of earlier species, with hobbit-like stature.

The dwarfed H. erectus hypothesis is based on the fact that the evolutionary pressures of island life often cause mammals to differ in size from their mainland relatives. Over time, small animals enlarge because there are fewer predators and big species shrink because there are fewer resources. H. erectus fossils at least 1.2 million years old have been found on the nearby island of Java. On Flores the “island rule” led to the evolution of giant rats and pygmy stegodons (an extinct elephant cousin) — why not H. floresiensis from Javanese H. erectus?

Critics say it’s not clear island dwarfing would cause hominins to shrink this particular way, especially when it comes to skulls. There’s an assumption that once our ancestors evolved H. erectus-sized brains, they couldn’t go back. Plus, dwarfing would have occurred in just a few hundred thousand years. Researchers question if this is enough time for such significant evolutionary change.

Figure 3: CT-based reconstruction of SOA-MM1 and the results of Elliptic Fourier Analysis of the molar crown contour.

Alternatively, the hobbits may have descended from tinier, older ancestors such as Homo habilis or Australopiths. The trouble here is no fossils from these species have been found outside of Africa. Scientists doubt they were capable of long-distance migration over land and sea. Even during the Ice Age, when global sea levels were lower, Flores seems to have been nearly 12 miles from the closest neighboring islands.

Abstract

The evolutionary origin of Homo floresiensis, a diminutive hominin species previously known only by skeletal remains from Liang Bua in western Flores, Indonesia, has been intensively debated. It is a matter of controversy whether this primitive form, dated to the Late Pleistocene, evolved from early Asian Homo erectus and represents a unique and striking case of evolutionary reversal in hominin body and brain size within an insular environment1,2,3,4. The alternative hypothesis is that H. floresiensis derived from an older, smaller-brained member of our genus, such as Homo habilis, or perhaps even late Australopithecus, signalling a hitherto undocumented dispersal of hominins from Africa into eastern Asia by two million years ago (2 Ma)5,6. Here we describe hominin fossils excavated in 2014 from an early Middle Pleistocene site (Mata Menge) in the So’a Basin of central Flores. These specimens comprise a mandible fragment and six isolated teeth belonging to at least three small-jawed and small-toothed individuals. Dating to ~0.7 Ma, these fossils now constitute the oldest hominin remains from Flores7. The Mata Menge mandible and teeth are similar in dimensions and morphological characteristics to those of H. floresiensis from Liang Bua. The exception is the mandibular first molar, which retains a more primitive condition. Notably, the Mata Menge mandible and molar are even smaller in size than those of the two existing H. floresiensis individuals from Liang Bua. The Mata Menge fossils are derived compared with Australopithecus and H. habilis, and so tend to support the view that H. floresiensis is a dwarfed descendent of early Asian H. erectus. Our findings suggest that hominins on Flores had acquired extremely small body size and other morphological traits specific to H. floresiensis at an unexpectedly early time.

Nature volume 534, pages245–248 (09 June 2016)