|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 10, 2017 20:34:14 GMT

Figure 3: Overview of the anthropogenic modifications observed on the Neandertal remains from the Troisième caverne of Goyet (Belgium). Comparative taphonomic analysis of the fauna from the Troisième caverne Due to the large size of the Goyet faunal collection (>30,000 specimens), only a sample from Dupont’s excavation was examined (see Methods; Supplementary Fig. S2 and Supplementary Table S5). The skeletal material analysed corresponds mostly to long bone shaft fragments from various species that were mixed together within the collection and did not appear to have been previously sorted. We focused on remains from levels 3 and 2, which yielded the Neandertal remains, and on material from the same storage trays containing the human remains in order to have an overview of the associated faunal spectrum and assess food procurement and management strategies. Horse and reindeer are by far the most frequent species in the studied assemblage (86% of the 1,556 identified specimens; Supplementary Table S5). No rodent toothmarks were observed, carnivore remains are relatively sparse and carnivore damage is extremely rare on the Neandertal, horse and reindeer remains (Table 2), indicating carnivores to have had limited access to the bone material. Anatomical profiles reveal numerous similarities between the Neandertal sample on one hand and horse and reindeer on the other (Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Fig. S13). The tibia is the most abundant element of all three species, whereas the axial skeleton and extremities of the forelimb and hindlimb are poorly represented. Bones of the hindlimb are better represented for all three species compared to forelimb elements, this is especially the case with the Neandertal material. The only notable difference between the faunal and Neandertal remains is the high representation of cranial elements for the latter. Unfortunately, the absence of contextual data precludes an analysis of the spatial distribution of both the faunal and Neandertal remains within the Troisième caverne.  Figure 4: Retouching marks (b1,b2) and cutmarks (c1,c2) present on the Goyet Neandertal bones (example of femur III). The most intensely processed Neandertal elements are femurs and tibias (Supplementary Fig. S7), which are also the bones with the highest nutritional content (meat and marrow). The same pattern was documented for horse and reindeer bones. Overall, anthropogenic marks on the Neandertal remains match those most commonly recorded on the faunal material (Supplementary Figs S14–S16). All three taxa were intensively exploited, exhibiting evidence of skinning, filleting, disarticulation and marrow extraction. However, the Neandertal remains stand out as they show a high number of percussion pits (Table 2), which may be linked to the thick cortical structure of Neandertal long bones. Although the Neandertal remains show no traces of burning, the possibility that they may have been roasted or boiled cannot be excluded. The high number of cutmarks and the fact that DNA could be successfully extracted are, however, inconsistent with this possibility44,45,46. Lastly, similar to what has been noted at other sites40,41,47, the Neandertal retouchers are made on fragments of dense bones with comparable mechanical properties to the horse and reindeer bones. At Goyet, as at several French Middle Palaeolithic sites, large bone fragments of medium and large-sized animals were selected40,41,48,49,50,51. Among the Goyet Neandertal material, the largest and thickest fragments were also selected, as was the case at Les Pradelles16 and Krapina42. Interestingly, a femur and tibias of cave bears were also among the retoucher blanks selected by Neandertals at Scladina52. The observed patterns of faunal exploitation can be interpreted as the selective transport of meat and marrow rich elements to the site that were subsequently intensively processed. However, this apparent pattern may reflect a collection bias favoring the largest and most easily identifiable fragments. Similarities in anthropogenic marks observed on the Neandertal, horse and reindeer bones do, however, suggest similar processing and consumption patterns for all three species.  Figure 5: Percussion pits (b1,b2) and percussion notch (c1,c2) present on the Goyet Neandertal bones (example of femur I). |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 12, 2017 20:33:07 GMT

Our results show that the Neandertals from the Troisième caverne of Goyet were butchered, with the hypothesis of their exploitation as food sources the most parsimonious explanation for the observed bone surface modifications. Goyet provides the first unambiguous evidence of Neandertal cannibalism in Northern Europe and given the dates obtained on the Neandertal remains, it is most likely that they were processed by their fellow Neandertals as no modern humans are known to have been in the region at the time17,23. However, the available data make it impossible to determine whether the modifications observed on the Neandertal skeletal material represent symbolic practices or simply result from the processing of immediately available sources of food. In addition, Goyet is the first site to have yielded multiple Neandertal bone retouchers. It has been proposed that Middle Palaeolithic retoucher blanks were by-products of the processing of carcasses for food consumption40,41, which may have been selected to be re-used51. The data at hand do not allow us to propose a different scenario for the Goyet retouchers made on Neandertal bones. However, the freshness of the blanks used suggests that Neandertals may have been aware that they were using human remains. Whether this was part of a symbolic activity or induced by a functional motivation cannot be attested, as was the case for the La Quina Neandertal retoucher43. Although the Goyet late Neandertals date to 40.5–45.5 ky calBP, the lack of reliable contextual information makes it impossible to associate them with any of the technocomplexes from the site. However, coeval Mousterian assemblages are known from sites in the Mosan Basin, as at unit 1A of Scladina53, located only 5 km from Goyet, layer CI-8 of Walou Cave54, and layer II of Trou de l’Abîme at Couvin55 (Supplementary Note S2). While the LRJ is known from two sites in Belgium, Spy and Goyet, with its first appearance dated at other sites to around 43–44 ky calBP23,56), no reliable information is currently available for its regional chronology. Given the direct 14C dates obtained for the Goyet Neandertals, it is impossible to securely associate them with either the Mousterian occupation(s) or the LRJ.  In terms of the region’s late Neandertal mortuary practices, four sites within an approximately 250 km radius around Goyet produced Neandertal remains reliably dated to between 50–40 ky calBP (Supplementary Fig. S1). Interestingly, none of these sites produced evidence for the treatment of the corpse similar to that documented for Goyet. Two Belgian sites, Walou Cave and Trou de l’Abîme, produced, respectively, a premolar and a molar55,57. Although impossible to infer the behavioural signature represented by these remains, given their state of preservation it is highly unlikely that they involved funerary practices, including burial. In Germany, the Neandertal individuals from Feldhofer, including Neandertal 1, are possibly associated with the “Keilmesser group”, a late Middle Palaeolithic technocomplex58,59 unknown at Goyet (Supplementary Note S2). Neandertal 1 comprises elements of the cranial and postcranial skeleton of a single individual. Despite cutmarks on the cranium, clavicle and scapula, the long bones are intact and damage to still articulated skeletal elements during their recovery indicates that at least part of the skeleton may have originally been in anatomical connection60,61. Finally, at Spy, direct dates obtained on the two Neandertal adults place them within the current chronology of the LRJ62, although the association between the human remains and this technocomplex is uncertain due to the lack of contextual information. A recent reassessment of the Spy specimens and their context suggests that both individuals were buried63. And, it is worth noting that the most complete individual, Spy II, was originally described as a complete skeleton found in a contracted position. Moreover, the completeness of the skeleton and the absence of post-depositional alterations suggest the body to have been rapidly protected63. Considerable diversity is evident in the mortuary behaviour of the late Neandertal populations of Northern Europe, possibly involving both primary and secondary deposits, alongside other types of practices, including cannibalism. Despite low genetic diversity amongst late Neandertal populations, the presence of various late Middle Palaeolithic technocomplexes, as well as the LRJ, nevertheless suggests significant behavioural variability amongst these groups in Northern Europe. Rougier, H. et al. Neandertal cannibalism and Neandertal bones used as tools in Northern Europe. Sci. Rep. 6, 29005; doi: 10.1038/srep29005 (2016). |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 16, 2017 20:28:23 GMT

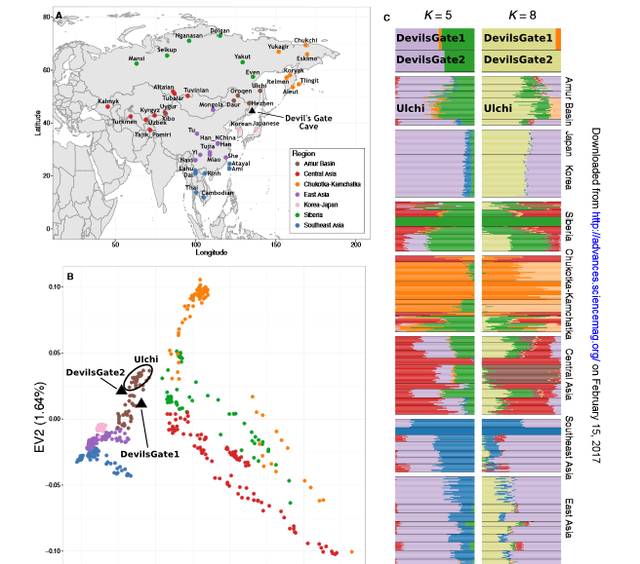

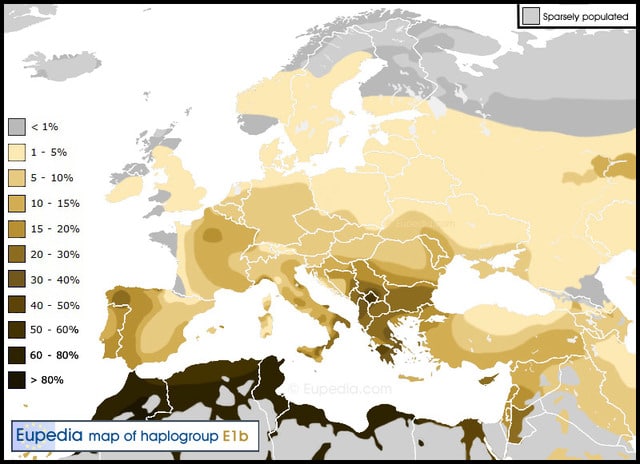

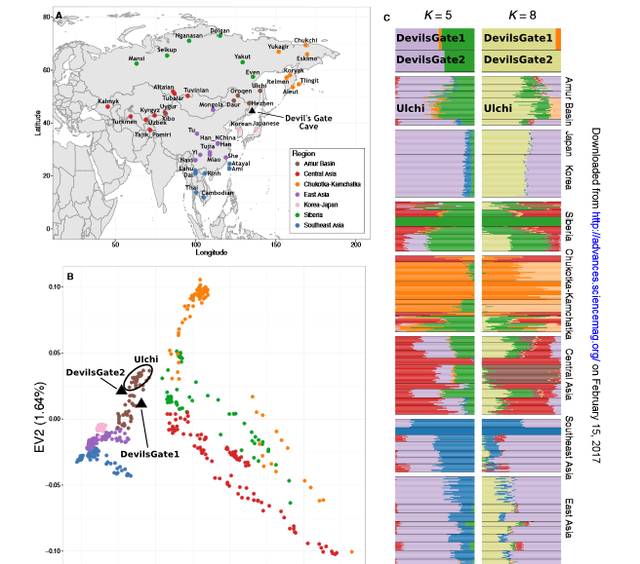

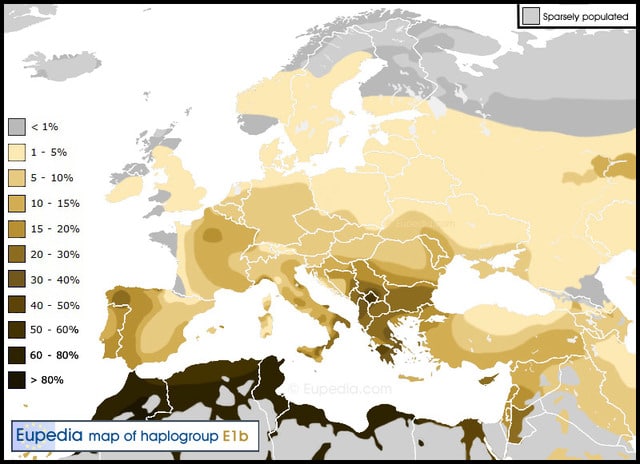

The ancestors of both modern Europeans and Asians have interbred with Neanderthals some 50,000 years ago. Researchers who are looking at DNA by race have wondered why East Asians have greater proportion of the ancestry compared to Europeans. New research reveals that the heavy-browed Neanderthals bred with East Asians on numerous occasions thus contemporary East Asians have higher levels of Neanderthal DNA according to studies which were published in the American Journal of Human Genetics. The study that was published in Science Advances is the first to obtain data on nuclear genome from ancient mainland in East Asia and compare the results to modern East Asian population. Findings of the study revealed that there were no major migratory interruption for over seven millennia. As a result of this, some contemporary ethnic groups share a very similar genetic makeup with ancient hunters from the Stone Age.  In contrast, Western Europe have had sustained migrations of early farmers from the Levant who overwhelmed the hunter-gatherer populations. A wave of horse riders from Central Asia soon came after the farmers during the Bronze Age. These events have been driven by the success of emergent technologies like metallurgy and agriculture as reported in Science Daily. The two studies both concluded that for living East Asians to carry a high percent of Neanderthal genes, their ancestors must have bred with them on multiple occasions. However, findings published in the journal Nature revealed that Neanderthals in Europe died out around 40,000 years ago which baffled scientists. How could Neanderthals breed with East Asians for a second time if they died out. According to researchers, it is also possible that Europeans have watered down their Neanderthal DNA by breeding with Africans who had no Neanderthal DNA. The frequency of haplogroup E1b is as high as 60% in southern Europe, where native Europeans and Africans interbred. On the contrary, East Asians may not have bred with Africans who did not carry Neanderthal DNA as haplogroup E is almost non-existent in East Asia. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 18, 2017 20:22:44 GMT

"As the last surviving species of humans on the planet, it is tempting to assume our modern faces sit at the tip of our evolutionary branch," says Chris Stringer, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, as he joins me in the gallery. "And for a long time, that has been what the fossils seemed to indicate," he continues. "Around 500,000 years ago, there was a fairly widespread form of Homo heidelbergensis that has a face somewhat intermediate between that of a modern human and Neanderthals. For a long time, I argued this was our common ancestor with Neanderthals."  Stringer shows me the cast of a real H. heidelbergensis cranium that was found at Broken Hill in Zambia in the 1920s, and which is now kept safely in the museum's fossil collection. It is the same skull that the little boy stood in front of earlier. By comparison the Neanderthal face was huge, with an enormous nose and the front of the face pulled forward. Around the cheeks the skull curved outwards, rather than being hollowed out. To our eyes, this would have given them a puffy appearance. They also had a far flatter forehead than we do, while above their eyes was a pronounced double arch of the brow-ridge that hung over the rest of their face. H. heidelbergensis had a slightly flatter face than the Neanderthal and a smaller nose, but no canine fossa. They also had an even more pronounced brow-ridge than that seen in Neanderthals.  For decades, most anthropologists agreed that Neanderthals had retained many of these features from H. heidelbergensis as they evolved and developed a more protruding jaw, while our own species went in a different direction. That was until the 1990s, when a puzzling discovery was unearthed in the Sierra de Atapuerca region of northern Spain. In a sinkhole in the mountains, fragments of a small, flat-faced skull were unearthed, alongside several other bones. The remains were identified as belonging to a previously unknown species of hominin. It was called Homo antecessor.  At first, this apparent contradiction was hand-waved away. The Atapuerca skull belonged to a child, aged around 10 to 12 years old. It is difficult to predict what this youngster's face would have looked like in adulthood, because as humans age their skulls grow and change shape. "It was assumed that it would fill out and grow into something resembling heidelbergensis," says Stringer. However, later discoveries suggest this is not the case. "We now have four fragments from antecessor adult and sub-adult skulls," says Stringer. "It looks like they maintain the morphology we see in the child's skull." |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 28, 2017 20:13:06 GMT

The last Neanderthal died 40,000 years ago, but much of their genome lives on, in bits and pieces, through modern humans. The impact of Neanderthals' genetic contribution has been uncertain: Do these snippets affect our genome's function, or are they just silent passengers along for the ride? In Cell on February 23, researchers report evidence that Neanderthal DNA sequences still influence how genes are turned on or off in modern humans. Neanderthal genes' effects on gene expression likely contribute to traits such as height and susceptibility to schizophrenia or lupus, the researchers found. "Even 50,000 years after the last human-Neanderthal mating, we can still see measurable impacts on gene expression," says geneticist and study co-author Joshua Akey of the University of Washington School of Medicine. "And those variations in gene expression contribute to human phenotypic variation and disease susceptibility."  Previous studies have found correlations between Neanderthal genes and traits such as fat metabolism, depression, and lupus risk. However, figuring out the mechanism behind the correlations has proved difficult. DNA can be extracted from fossils and sequenced, but RNA cannot. Without this source of information, scientists can't be sure exactly if Neanderthal genes functioned differently than their modern human counterparts. They can, however, look to gene expression in modern humans who possess Neanderthal ancestry. In this study, researchers analyzed RNA sequences in a dataset called the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project, looking for people who carried both Neanderthal and modern human versions of any given gene -- one version from each parent. For each such gene, the investigators then compared expression of the two alleles head-to-head in 52 different tissues. "We find that for about 25% of all those sites that we tested, we can detect a difference in expression between the Neanderthal allele and the modern human allele," says the study's first author, UW postdoctoral researcher Rajiv McCoy. Expression of Neanderthal alleles tended to be especially low in the brain and the testes, suggesting that those tissues may have experienced more rapid evolution since we diverged from Neanderthals approximately 700,000 years ago. "We can infer that maybe the greatest differences in gene regulation exist in the brain and testes between modern humans and Neanderthals," says Akey. |

|