|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 10, 2023 21:35:01 GMT

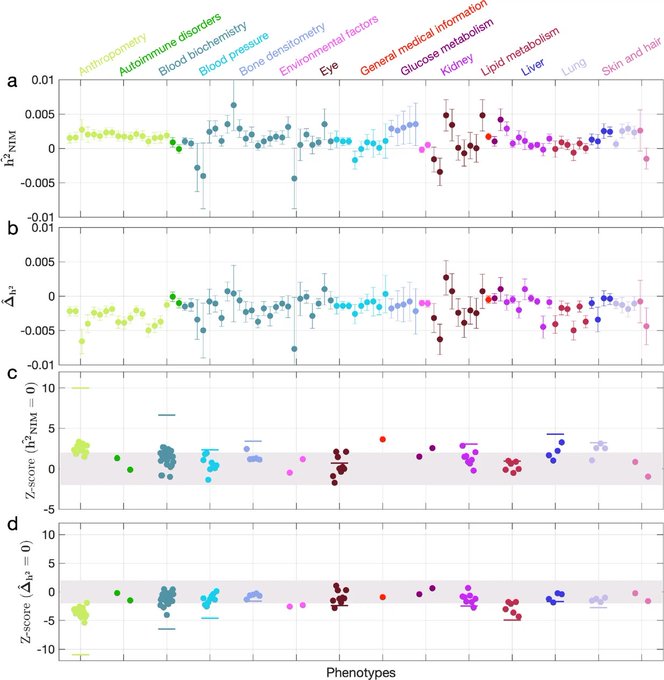

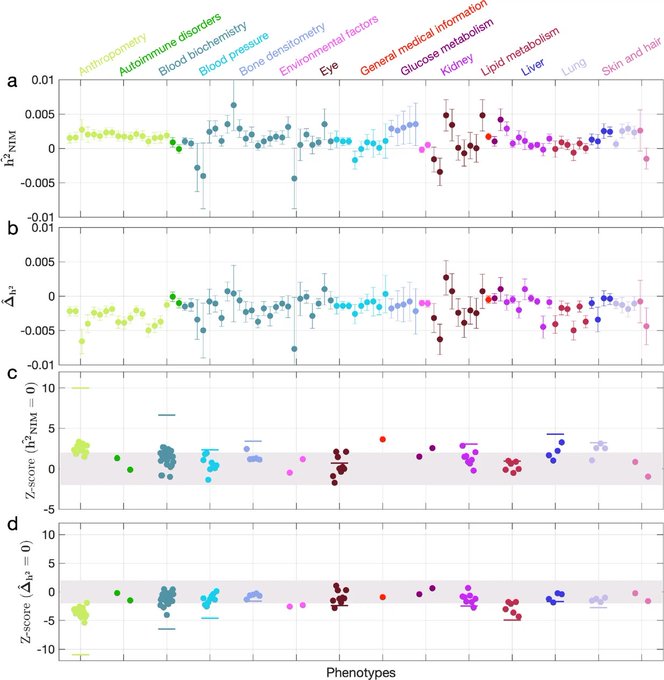

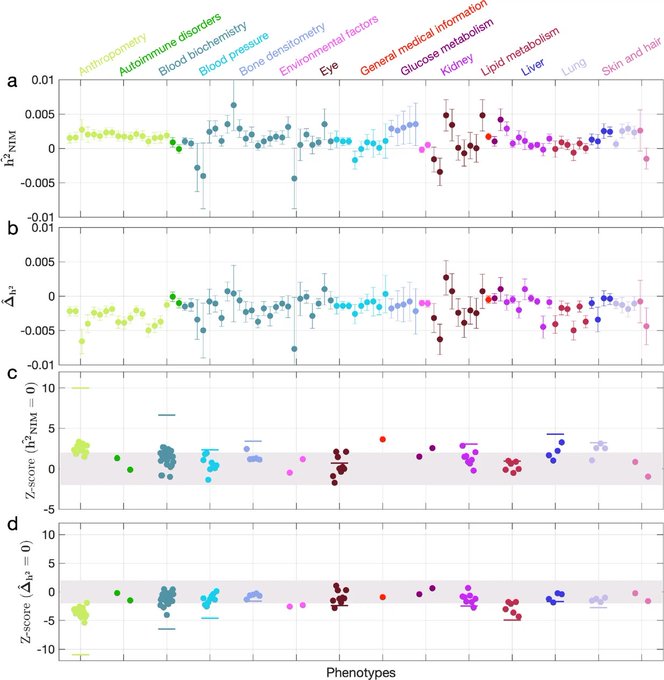

A study from a multi-institutional research team has found that Neanderthal DNA can actively influence some human traits, particularly those involved in immunity. The research, published in eLife, also suggests that modern human genes are winning out over Neanderthal ones over successive generations. Neanderthal DNA in modern-day genomes The genomes of some present-day humans can contain a surprising amount of Neanderthal DNA. People with ancestors who migrated out of Africa, particularly those of European ancestry, can have as much as 1–4% of their genome made up of Neanderthal DNA. These are likely remnants of interbreeding between ancient humans and Neanderthals some 50,000 years ago. The introduction of Neanderthal DNA into the gene pool may have helped these ancient humans survive in the cold European climate as they encountered new environments in their migration out of Africa. For example, studies have shown that Neanderthal DNA can influence our nose shape or even our immune response to the flu. However, the extent to which Neanderthal DNA contributes towards complex human traits has been difficult to explore due to the evolutionary history of different populations and the relatively small proportion of Neanderthal DNA in modern-day genomes. The researchers in the current study investigated this in more detail using data from the UK Biobank, a vast database of genetic and trait information of almost 300,000 Britons of non-African ancestry. 47 traits identified Over 235,000 genetic variants from the database were analyzed that were likely to have originated from Neanderthals. Of these, 4,303 variants were found to play a key role in influencing 47 distinct traits in modern humans. These include traits such as how fast someone can burn calories or natural immune resistance to certain diseases. Many identified traits have a significant influence on the immune system – however, the findings indicate that overall, modern human genes are winning out over successive generations. Developing upon previous studies that could not entirely exclude modern human variants, the new study also utilized more precise statistical and computational methods to home in on variants they could attribute to Neanderthal DNA.  “Interestingly, we found that several of the identified genes involved in modern human immune, metabolic and developmental systems might have influenced human evolution after the ancestors’ migration out of Africa,” said Dr. April (Xinzhu) Wei, an assistant professor of computational biology at Cornell University and co-lead author of the study. “We have made our custom software available for free download and use by anyone interested in further research.” New evolutionary insights Though limited by data almost exclusively from white individuals living in the UK, the novel computational techniques developed for this study lead to an increase in gleaning new evolutionary insights. For example, enabling the analysis of larger and more diverse databases to delve deeper into the influence of ancient genetics on humans today. “For scientists studying human evolution interested in understanding how interbreeding with archaic humans tens of thousands of years ago still shapes the biology of many present-day humans, this study can fill in some of those blanks,” said Dr. Sriram Sankararaman, associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles and the senior author of the study. “More broadly, our findings can also provide new insights for evolutionary biologists looking at how the echoes of these types of events may have both beneficial and detrimental consequences.” Reference: Wei X, Robles CR, Pazokitoroudi A, et al. The lingering effects of Neanderthal introgression on human complex traits. eLife. 2023;12:e80757. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80757 This article is a rework of a press release issued by Cornell University. Material has been edited for length and content. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 8, 2023 3:24:43 GMT

Amongst the remains of the Neanderthal inhabitants of a cave in France, researchers have uncovered a hip belonging to a modern human baby. However, after noticing differences between the ancient ilium and that of more recent neonates, the authors of a new study say the infant may represent a previously unknown early lineage of Homo sapiens.  The Grotte du Renne cave is among the most intriguing Paleolithic sites in Europe as it is believed to have been inhabited around the time that modern humans replaced Neanderthals. Within the cave, researchers have uncovered large numbers of stone tools that are representative of the Châtelperronian techno-cultural complex, which arose during this transition period. Scholars are divided as to which species invented this industry, with some believing Neanderthals came up with it by themselves, others claiming that it was the work of anatomically modern humans (AMH), and others speculating that the two hominids may have worked together. Interestingly, until now, only Neanderthal remains had been found in the Châtelperronian layer within Grotte du Renne, although modern human fossils have been noted in other caves associated with these items. In light of this ongoing debate, the newly analyzed pelvis may have just thrust the narrative in a new direction. Comparing the specimen to two known infant Neanderthal hip bones and those of 32 recent human deceased neonates, the study authors note that its shape differs significantly from the Neanderthal ilium and is much more in line with AMH morphology. However, the ancient hip also fell slightly outside the bounds of variation seen in modern human infants, displaying “a more laterally oriented posterior-superior iliac spine.” “We propose that this is due to its belonging to an early modern human lineage whose morphology differs slightly from present-day humans,” write the study authors. Noting that this lineage has never previously been documented, the researchers say the infant was probably a member of the AMH populations that coexisted with the last Neanderthals during the transition from the Middle to the Upper Paleolithic, 41,000 to 45,000 years ago. Furthermore, the presence of these ancient modern humans in Grotte du Renne suggests that they may have lived alongside Neanderthals at the time that the Châtelperronian industry emerged. “The makers of the Châtelperronian could then be human groups where Neanderthals and AMH coexisted,” write the researchers. This, in turn, implies that the development of the Châtelperronian may have “resulted from cultural diffusion or acculturation processes with possible population admixture between the two groups.” In other words, Neanderthals may have upgraded their technologies after observing their modern human neighbors, resulting in a hybrid industry that came to dominate parts of Europe until the last Neanderthals disappeared. The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports. www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-39767-2 |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 8, 2023 19:39:35 GMT

Almost 200,000 years ago, a group of Neanderthals in southwest France constructed a series of odd structures out of broken stalagmites deep inside a cave. Arranged in two large circles and four small stacks, the carefully positioned formations have baffled researchers since their discovery in 1990 and hint at unexpectedly complex Neanderthal behaviors.  Early analyses of the mysterious assemblies revealed that they were at least 47,000 years old, yet the untimely death of the lead researcher halted the investigation for over 20 years. However, in 2016, scientists finally revisited the site, using uranium-series dating to determine that the stalagmites had been in place for around 176.5 thousand years. “Early Neanderthals were the only human population living in Europe during this period,” wrote the study authors. “Our findings suggest that their society included elements of modernity, which can now be proven to have emerged earlier than previously thought. These include complex spatial organization, fire use, and deep karst occupation.” Indeed, prior to this discovery, evidence for cultural practices and complicated social behaviors was absent from the Neanderthal record. Yet the researchers say that the creation of these structures required “a necessary simultaneous realization of different tasks and consequently, the existence of some degree of social organization.” Furthermore, the fact that the arrangements were located “336 meters [1,102 feet] from the entrance of the cave indicates that humans from this period had already mastered the underground environment, which can be considered a major step in human modernity.” Describing the two annular structures, the researchers reveal that one measures 6.7 by 4.5 meters (22 by 14.8 feet) while the other is 2.2 by 2.1 meters (7.2 by 6.9 feet). “Overall, about 400 pieces were used, comprising a total length of 112.4 m [368.8 feet] and an average weight of 2.2 tons of calcite,” they say. Weirdly, the Neanderthal builders of these bizarre structures chose not to use whole stalagmites, typically opting for the middle section while discarding the root and tip. Evidence for the use of fire was also detected on 123 of the stalagmites. Unsurprisingly, the analysis left the researchers with more questions than answers. For instance, “What was the function of these structures at such a great distance from the cave entrance? Why are most of the fireplaces found on the structures rather than directly on the cave floor?” they ask. “Based on most Upper Palaeolithic cave incursions, we could assume that they represent some kind of symbolic or ritual behavior, but could they rather have served for an unknown domestic use or simply as a refuge?” Though not able to answer any of these questions, the study authors do conclude that “the Neanderthal group responsible for these constructions had a level of social organization that was more complex than previously thought for this hominid species.” |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 15, 2023 12:40:50 GMT

The study by researchers at South Korea's Pusan National University, which had been published in Science, found that over the past 400,000 years, breeding between the two extinct subspecies of human was influenced more by the climate than originally thought.

And the fossil of a 90,000-year-old human—found to have a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother, according to DNA testing—suggests that sex between the two subspecies was actually quite common.

The Denisovans, or Denisova hominins, are an extinct subspecies of human that lived from 500,000 to 30,000 years ago. Neanderthals, also an extinct subspecies, lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago.

Although the two subspecies favored different habitats most of the time—with Denisovans preferring cooler environments, and Neanderthals preferring the warmth—shifts in the Earth's orbit changed the distribution of vegetation, and the overall environment.

This caused an overlap in the two subspecies migration patterns, increasing the chances of them meeting and breeding.

The Earth's orbit around the sun determines seasonal fluctuations as well as long-term climate. For example, when the Earth is going through a cycle where it is closer to the sun, we experience a warmer climate.

Serbian scientist Milutin Milankovitch believed that periodic changes in the Earth's position relative to the sun determined long-term climate fluctuations, NASA reports. These changes were responsible for Ice Ages—periods of extreme cold driven by a reduction in the planet's temperature.

Scientists already knew that Neanderthal and Denisovans had sex, however they do not know when, where or how often it took place.

To find out more, researchers analyzed paleoanthropological evidence, genetic data and supercomputer simulations of past climate to assess if it had any impact, the study reported. They found that interglacial climates, and the way this shifted vegetation in certain habitats, meant there were more opportunities for the two species to encounter each other.

Recent paleogenomic research revealed that interbreeding was common among early human species. However, little was known about when, where, and how often this hominin interbreeding took place. Using paleoanthropological evidence, genetic data, and supercomputer simulations of past climate, a team of international researchers has found that interglacial climates and corresponding shifts in vegetation created common habitats for Neanderthals and Denisovans, increasing their chances for interbreeding and gene flow in parts of Europe and central Asia.

Contemporary humans carry in their cells a small amount of DNA derived from Neanderthals and Denisovans. "Denny," a 90,000-year-old fossil individual, recently identified as the daughter of a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother, bears testimony to the possibility that interbreeding was quite common among early human species. But when, where, and at what frequency did this interbreeding take place?

In a recent study published in Science on 10 August 2023, researchers from Korea and Italy have joined hands to answer this question. Using fossil data, supercomputer simulations of past climate, and insights obtained from genomic evidence, the team was able to identify habitat overlaps and contact hotspots of these early human species. Dr. Jiaoyang Ruan, Postdoctoral Researcher at IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP), South Korea, explains, "Little is known about when, where, and how frequently Neanderthals and Denisovans interbred throughout their shared history. As such, we tried to understand the potential for Neanderthal-Denisovan admixture using species distribution models that bring extensive fossil, archeological, and genetic data together with transient Coupled General Circulation Model simulations of global climate and biome."

The researchers found that Neanderthals and Denisovans had different environmental preferences to start with. While Denisovans were much more adapted to colder environments, such as the boreal forests and the tundra region in northeastern Eurasia, their Neanderthal cousins preferred the warmer temperate forests and grasslands in the southwest. However, shifts in the Earth's orbit led to changes in climatic conditions and hence vegetation patterns. This triggered the migration of both these hominin species towards geographically overlapping habitats, thus increasing the chance of their interbreeding.

The researchers further used insights gained from their analysis to determine the contact hotspots between Neanderthals and Denisovans. They identified Central Eurasia, the Caucasus, the Tianshan, and the Changbai mountains as the likely hotspots. Identification of these habitat overlaps also helped the researchers place 'Denny' within the climatic context and even confirmed the other known episodes of genetic interbreeding. The researchers also noted that the Denisovans and Neanderthals would have had a high probability of contact in the Siberian Altai during ~ 340-290, ~240-190 and ~130-80 thousand years ago.

To further elucidate the factors that triggered the 'east-west interbreeding seesaw,' the team examined the change in vegetation patterns over Eurasia over the past 400 thousand years. They observed that elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations and mild interglacial conditions caused an eastward expansion of the temperate forest into central Eurasia, and the dispersal of Neanderthals into Denisovan lands. On the contrary, lower CO2 concentrations and corresponding harsher glacial climate potentially caused a fragmentation of their habitats, leading to lesser interactions and interbreeding events.

"Pronounced climate-driven zonal shifts in the main overlap region of Denisovans and Neanderthals in central Eurasia, which can be attributed to the response of climate and vegetation to past variations in atmospheric CO2 and northern hemisphere ice-sheet volume, influenced the timing and intensity of potential interbreeding events," remarks senior author Axel Timmermann, Director, ICCP and Professor at Pusan National University, South Korea.

In summary, the study shows that climate-mediated events have played a crucial role in facilitating gene flow among early human species and have left lasting impressions on the genomic ancestry of modern-day humans.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Pusan National University. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:

Jiaoyang Ruan, Axel Timmermann, Pasquale Raia, Kyung-Sook Yun, Elke Zeller, Alessandro Mondanaro, Mirko Di Febbraro, Danielle Lemmon, Silvia Castiglione, Marina Melchionna. Climate shifts orchestrated hominin interbreeding events across Eurasia. Science, 2023; 381 (6658): 699 DOI: 10.1126/science.add4459

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 3, 2023 18:40:12 GMT

A flowery mystery has been puzzling scientists at Shanidar Cave, a rocky outcrop located on Bradost Mountain within a long mountain range in the Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq, where a Neanderthal grave was found stuffed full of pollen. While some believed it to be evidence of cultural funerary practices among Neanderthals, others thought it must be animals, and now research is suggesting a new contender: bees. Nine Neanderthal skeletons were found buried in Shanidar Cave during excavations in the 1950s and 60s, with a further body being discovered in a later dig. The number of remains and their organization appear to resemble a Neanderthal graveyard, with one individual having seemingly been laid to rest with a significant amount of pollen. The discovery had many questioning if it was evidence of a grand burial ritual, indicating this individual was of great significance, perhaps even a shaman. If true, it would indicate Neanderthals shared empathic characteristics with Middle Palaeolithic Homo sapiens. However, many have contested the claim, arguing that the pollen may have been deposited by animals dragging flowers to their burrows. Palynology may have solved the mystery, an area of science concerned with the study of plant pollen, spores, and microscopic plankton in both their living and fossilized forms. The pollen clumps found around the grave were a mixture of species that were unlikely to be in bloom at the same time, say the researchers behind a new review of the Shanidar Cave evidence. They are also more mixed than you would expect had whole flowers been placed into the grave, indicating the pollen arrived via a different vector. Animals had been suggested, but again this was in the context of them transporting whole flowers. So, who could be making the pollen mixtures? “The most likely is that the pollen was accumulated by nesting solitary bees,” explain the authors. “The pollen loads of individual bees can contain more than one species if they are foraging different species at once.” Bee burrows are present in the less trampled areas of Shanidar Cave, being a range of depths and most common at the rear of the cave close to the wall. These burrows are sometimes reinforced with silty clay and ancient examples were discovered during subsequent excavations of the cave. The corroded and flattened state of the pollen indicates it’s ancient and therefore was probably deposited around the same time the Neanderthals went into the ground, rather than having been brought in by the boots of archaeologists. However, if Arlette Leroi-Gourhan – the first archaeologist to posit the “Flower Burial” hypothesis – was correct in identifying immature grains among the pollen clumps, it’s possible these grains may have been deposited through a different mechanism, such as plants being dropped above the remains by humans, some other animal, or even the weather. It's curious that bees should be implicated in the “Flower Burial” hypothesis, as they themselves have been observed getting peculiar floral funerals at the hands of ants. In reality, the mounds of dead bees and botanical material are likely a way of storing either food or waste, rather than a dignified send-off.  Undoubtedly there remain many questions about the events that occurred in Shanidar Cave, but as far as this latest review is concerned, the “Flower Burial” hypothesis is not substantiated. “At this point, we can only conclude that the ‘Flower Burial’ hypothesis seems unlikely, that nesting bees were probably responsible for some of the pollen clumps – certainly the mixed ones – and that there is a possibility that if immature pollen were involved it could have come from plants placed over or under the body,” concluded the authors, who argue we may be missing the significance of the Shanidar Cave by focusing on the pollen. “Debates about the ‘Flower Burial’ have in many respects obscured its most significant aspect: that it was part of a tight cluster of what our evidence suggests were emplaced bodies that is practically unique in the Neanderthal realm. The potential implications of this behaviour for Neanderthals' sense of space and place are probably the most intriguing aspect of the Shanidar Cave Neanderthals, rather than whether an individual was buried with flowers.” The study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440323001024An earlier version of this article was published in August 2023. |

|