|

|

Post by Admin on Dec 8, 2014 13:54:15 GMT

There has been inordinate fascination with societal collapse, an issue outlined in the introduction to this Special Feature (1). The concept has intuitive appeal but ambiguous meaning, and has been applied to states, nations, or complex societies, in the sense that such entities rise and flourish, but eventually disintegrate and fail. Sociopolitical organization, economic weakness, and environmental or demographic trends have received emphasis. Change takes a long-term cyclic rhythm, at first organizing, then expanding and integrating, before sinking in disorder. Systemic failure in one synergistic network may destabilize adjacent structures. Other open questions concern the scale of collapse, the time frames involved, the key elements that fail, and whether the outcome is cataclysmic or eventually allows restructuring. Not all breakdowns are alike. This challenging concept and its attendant issues were first articulated by the Islamic historian Ibn Khaldun [after 1377 common era (CE)] (2), who identified the periodic rise and fall of dynasties as macrostructures in the history of sedentary civilizations. Beginning with the Roman Empire and continuing with its Islamic counterparts, he attributed demise to rural rebellions or outside invaders confronting a ruling hierarchy that had forfeited the solidarity of its supporters. Rather than a global history, Khaldun's work was an implicit critique of Islamic society that went beyond theological arguments. He faulted the greed and selfishness that came with power, at the expense of the common good.  Khaldun's writings were poorly disseminated, and Western interest in collapse was initially stimulated by Edward Gibbon (3), who, with laborious detail, attributed the decline and fall of the Roman Empire to moral decay and barbarian invasions, much like his predecessor had. Gibbon observed that Roman collapse had changed the sociopolitical map of Europe and the Mediterranean world, a transformation that continues to generate a secondary literature. Although Gibbon held to an ethical dimension, he recognized that Roman collapse could not be separated from historical processes that shaped the dynamic context of its time, and he was uneasy about the potential future failure of even more enlightened and powerful states. When the archaeological discoveries of the 19th century revealed a periodic failure of kingdoms and empires across the Near East, the collapse model became a durable theme of social and historical discourse. However, the message shifted: whereas ephemeral Eastern civilizations regularly dissolved in chaos, the comparative durability of ancient Rome improved the prospect that Western Europe might endure indefinitely. With the proliferation of biological analogues in the mid-1800s, ontogenetic or evolutionary qualities such as growth, maturity, and decline were used to interpret historical macrostructures. For social Darwinists, material culture became an index for the increasing achievements of civilization, in an era when the Industrial Revolution exuded the driving force of “progress.” The West was seen as a new empire, wherein technology would assure unlimited economic growth. Problems could and would be fixed by technological innovation. Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West (1918–1922) (4) was written in the wake of a world war and before the Nazi ascendance. He redefined ontogeny in humanistic terms that included premonitions of the authoritarian state. His “winter” would coincide with a demise of abstract thought, accompanied by empowerment of the rich, and the rise of caesarian, demagogic leaders. Spengler saw a society in deep crisis, and his prescient but pessimistic ideas anticipated the horrors of fascism and Stalinism. His insights remain pertinent for modeling alternative pathways of political resilience in the wake of collapse. By contrast, the French authors of the Annales School chose a nonlinear track to capture the rich detail of regional histories, and to develop an interdisciplinary method in which millennial demographic waves served as a bellwether of key interactive processes (5⇓–7). Disjunctures were attributed to competing economic systems, long-distance networking, warfare, or pandemics (8), ideas that gave impetus to world-system history (9⇓–11). The annalistes eventually turned to more humanistic studies that introduced environmental variability as an integral part of historical process (12, 13). Notable is the increasing diversity of perspectives about collapse, ranging initially from ethical and social, to ideological or ethnocentric, and eventually to interdisciplinary and systemic. The underlying ideas continue to echo. The salient concern today is the interface between environment and society, to require greater attention to social science and humanities perspectives. There has indeed been rapid growth of theoretical sophistication in regard to complexity and network theory, agent-based models, resilience theory, or tipping points. However, the challenge for a scientific study of historical collapse remains to develop comprehensive, integrated or coupled models, drawing upon the implications of qualitative narratives that go well beyond routine social science categories, to better incorporate the complexity of human societies (1).  Current research in historical collapse suggests a primary fascination with climatic change and environmental degradation as primary agents of change, but at the cost of less attention to the necessary cross-disciplinary integration. Indeed, the recent return to environmentalism is not about a fresh interest in the environment–society interface, but a continuing failure to appreciate the complexity of such interrelationships. At issue is not whether climatic change is relevant for sociohistorical change, but how we can deal more objectively with coupled systems that include a great tapestry of variables, among which climatically triggered environmental change is undeniably important. The SI Text reviews the problematic revival of environmental determinism in regard to the Akkadian collapse, as well as the purported societal passivity about anthropogenic degradation and potential future collapse. The Old World case studies range from early historical times to the threshold of globalization, with additional examples outlined in the SI Text, or presented in the various research articles of this Special Feature of PNAS. Examined at different levels of detail, these cases help single out more important, interactive variables, to estimate time scales for transformation, and explore the roles of preconditioning, triggering and reconstituting processes. The ultimate goal would be to design complex simulation models that incorporate sophisticated societal components and that can be validated (1). This presentation attempts to transcend simple assumptions or truisms and monocausal explanations, by dissecting historical examples so as to illustrate the full palette of social-ecological variables and why they are so important for resilience within coupled systems. Some current models for change pay careful attention to biophysical variables that may affect feedbacks, but then go on to simply fit a group of societal factors into a few preconceived categories, supported by tertiary digests of no better than mixed value, to “explain” a particular outcome by assumed, axiomatic processes. Instead, our five case studies (later and in the SI Text) identify important, qualitative variables and track their roles and interplay in systemic outcomes. Although difficult to simulate, societal inputs and feedbacks are more common than environmental variables. The case studies also offer temporal parameters for transformation. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Dec 10, 2014 14:13:58 GMT

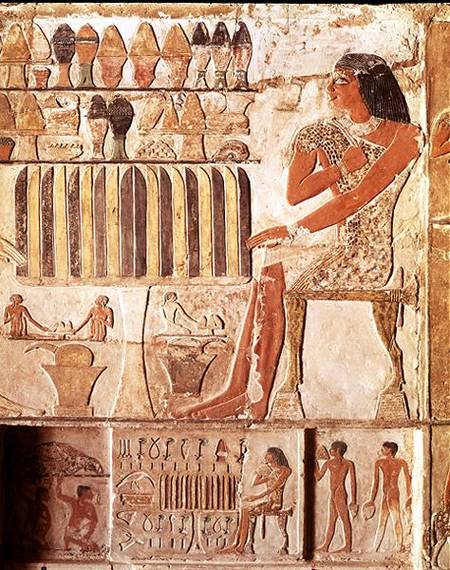

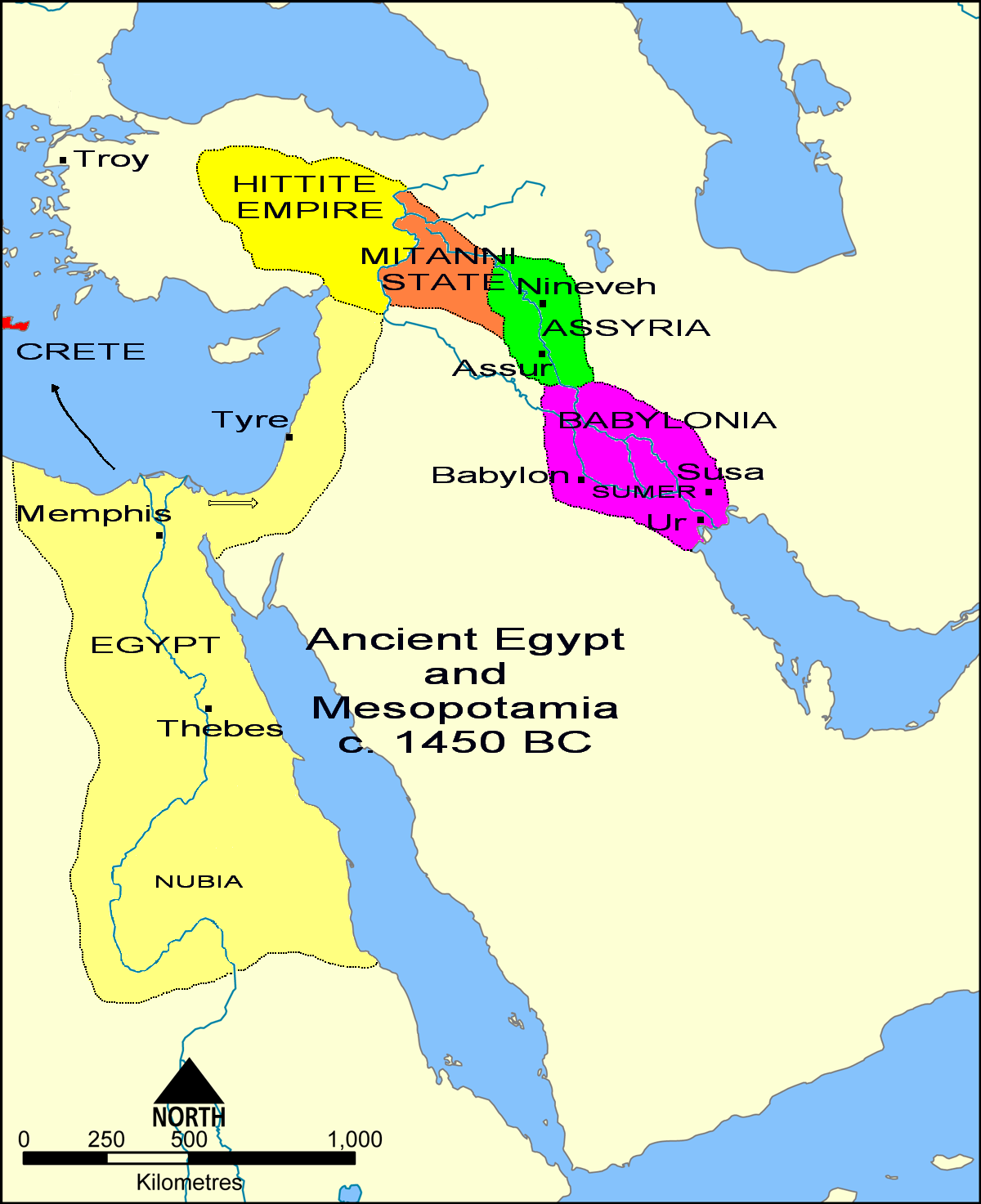

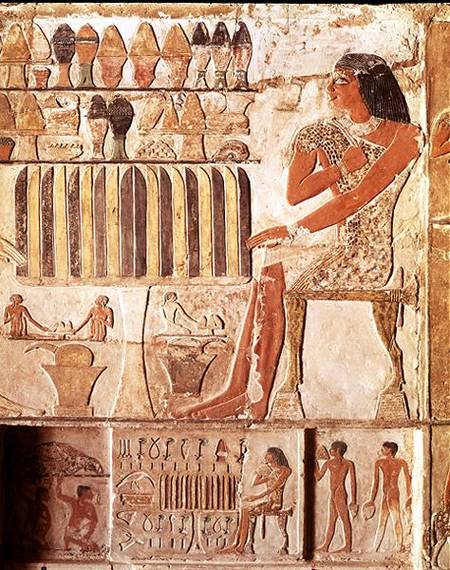

Anatomy of a Collapse: Old Kingdom Egypt The historical cycle of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (14) closed shortly after the improbably long reign of Pepi II [∼2278–2184 before CE (BCE)], the last significant ruler of the sixth Dynasty. Such long periods of rule can lead to issues of succession, and royal authority promptly collapsed at the death of Pepi II, judging by a cluster of approximately 20 powerless kinglets, marking the seventh-eighth dynasties, a very short time span, perhaps from 2181 to 2160 BCE. Egypt broke apart into several feuding provincial powers, controlled by members of the old elite or a novel genre of warlords, to be reunited through force of arms after approximately 2040 BCE by a new, 11th Dynasty. Didactic Literature. An interval of approximately 120 to 200 y (ref. 15, table S7; ref. 16, p 464), known as the First Intermediate Period (dynasties 9–10), represents a radical sociopolitical transformation, documented by written records and archeology. Instead of burial near Memphis, the rich or powerful began to build rock tombs near their provincial land-holdings. Wealth was dispersed to new centers, with economic growth, artistic and cultural change, and a shift to a different style of social complexity (17). Some of the elite were deeply disturbed by the course of events, leading to a body of didactic literature (labeled as instructions, lamentations, or prophecies) that became literary classics during the Middle and New Kingdoms, when they were used in the schooling of young scribes.  Few such tracts have the necessary authenticity of historical descriptions, but they do represent an insider perspective on Egyptian cultural memory of a painful transition (ref. 18, p. 109–113). The autobiography of Ankhtifi, a southern provincial governor [ninth Dynasty, ∼2120 (?) BCE], was inscribed in a rock-cut tomb. The full list of woes enumerated had not been previously used in literary convention, and was not a mere figure of speech. The text elliptically reports rampant civil war, famine, and starvation caused by Nile failure, mass dying or aimless dislocation of starving people, cannibalism (sic), wanton tomb or cemetery violations, and dispossession of the elite. Other, less authentic admonitions of the era amplify the themes of poverty, anarchy, and the upending of social roles. The basic message is a breakdown of the “cosmic order” and social justice, perhaps in the wake of an environmental disaster. However one chooses to interpret such writings, there was no central government, while justice, order, or respect for tradition fell by the wayside during the nadir of collapse, presumably the seventh to eighth dynasties. Onset of Economic Decline. During the sixth dynasty, central authority was steadily diluted by privileges granted to courtiers around the throne. Mortuary temples were already built for pharaohs of the fourth dynasty, institutions that engaged groups of priests, paid by the treasury in perpetuity, whereas such foundations and their farms were exempt from taxes, much as nonprofit corporations are today. Gradually such privileges were accorded to other powerful men at court, a pattern accelerating during sixth Dynasty times until a significant part of the prime lands was removed from the fiscal rolls, even as the state continued to support the upkeep of mortuary cults (“entitlements”). Economic decline also resulted from breakdown of the vital foreign trade, mainly carried out over the entrepot of Byblos (now Jubail, Lebanon). Cedar and fir were imported for shipbuilding, or luxury goods such as wine and olive oil, for elite use. Pharaoh is likely to have profited greatly from such transactions, but archeology shows that, during the reign of Pepi II, Byblos was destroyed by the Akkadians, its Egyptian imports ending abruptly (19) and then interrupted for 250 y. That would have cut off a critical source of royal revenue, weakening pharaoh's personal power.  Environmental Trigger. Inferred from the admonitions, Nile failures are quite plausible in view of the limnological record of Lake Turkana: fed to approximately 90% by the Omo watershed in mountainous western Ethiopia, an area with climatic conditions similar to those of the Blue Nile. Prominent and dated beach ridges indicate a sporadic, early to mid-Holocene overflow of this nonoutlet lake, through a series of swamps to the Sobat and White Nile rivers (20). Together with diatom assemblages, alkalinity levels, and Omo detrital silicates, the lake levels offer a proxy record for Blue Nile behavior, but the chronology is only approximate (21). A decrease in Omo material approximately 2800 (calibrated years) BCE was followed by an abrupt change in water chemistry, to a closed, alkaline-saline lake, approximately 2400 BCE. This coincided with a late fourth Dynasty shift to downcutting (i.e., channel incision) of the Nile at Giza (22), implying a pattern of poor or indifferent floods that would only inundate parts of the flood basins. Omo influx was minimal approximately 2100 BCE, but sharply greater 2000 to 1800 BCE, before declining again. Considering the partial match of these rough dates, it is possible but unproven that Nile failures may have helped trigger collapse of the old kingdom. Civil Wars. The Egyptian record after Pepi II not only points to dynastic instability, but also includes direct and indirect evidence of civil wars during the ninth to 11th dynasties. Permanent reunification of Egypt toward approximately 2016 BCE required several bloody campaigns until the victory of a Theban dynasty over the northern center of Heracleopolis, but even then the Delta remained to be subjugated (23, 24). The Theban vizier later usurped the throne, waging intermittent warfare to ascend to the kingship as Amenemhet I (∼1985–1956 BCE) of the 12th dynasty, against vigorous opposition by some of the elites (ref. 16, p. 493–495; and ref. 25). He was later assassinated. He and his successors had been supported by the provincial warlords of Middle Egypt (24), who retained considerable power until approximately 1850 BCE, when a new king phased out or eliminated the office of provincial governors—potential military contenders—and returned Egypt to a more traditional, centralized autocracy. Demilitarization followed, with reemergence of a middle class (ref. 16, p. 506; and ref. 25), ending 300 y of intermittent warfare and civil strife. The collapse after Pepi II had evidently unleashed unwelcome feedbacks that repeatedly favored destructive military unrest, variously coupled with both elite contestation and resilience. The didactic literature implies that the goal of reunification remained central to the cosmic order ascribed to by key national power groups.  Concatenation. The details marshaled here illustrate the immense complexity of collapse. The economic prosperity of Egypt had declined through the course of the sixth Dynasty, inversely to the growing wealth and power of now-hereditary provincial governors. The expansion of mortuary endowments, fiscal stagnation, decentralization of authority, and loss of hegemony over eastern Mediterranean trade had served to precondition Egypt for collapse across 160 y or more. Nile failures probably unleashed a severe subsistence crisis that helped trigger an economic breakdown near the end of Pepi II's reign, but other factors were also involved (17, 26). Contending elite groups may originally have used an impending crisis of succession to undermine royal legitimacy, in an effort to steer more power to the provinces. However, they discovered that social anarchy is difficult to contain when institutional structures falter. Amid social chaos and insecurity analogous to that of modern Somalia, ancient Egypt experienced political simplification as the contestants repeatedly resorted to armed force. A concatenation of triggering economic, subsistence, political, and social forces probably drove Egypt across a threshold of instability, setting in train a downward spiral of cascading feedbacks. In the end, a semblance of the cosmic order was restored, with the support of new elites, but with the heavy hand of military men, even as the echoes of civil war continued to reverberate until the authoritarian rule of the Pyramid Age was reinstated (ref. 17; pp. 118–119 and 130–131). The initial breakdown took a few decades, but the processes of collapse played out on a centennial scale, as did reconstitution (16). This detailed analysis, with the advantage of a body of fragmentary but rich, written records, helps illustrate the true complexity of collapse. It involved more than an impersonal network of systemic interactions. It encompassed people, admittedly at cross purposes and with incomplete information, who ultimately sought to bring their country back together, consonant with their vision of the cosmic order. In the persons of military leaders and conflicted elites, one can gain a glimpse of the ambiguous notions that political and social resilience imply. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Dec 12, 2014 16:20:46 GMT

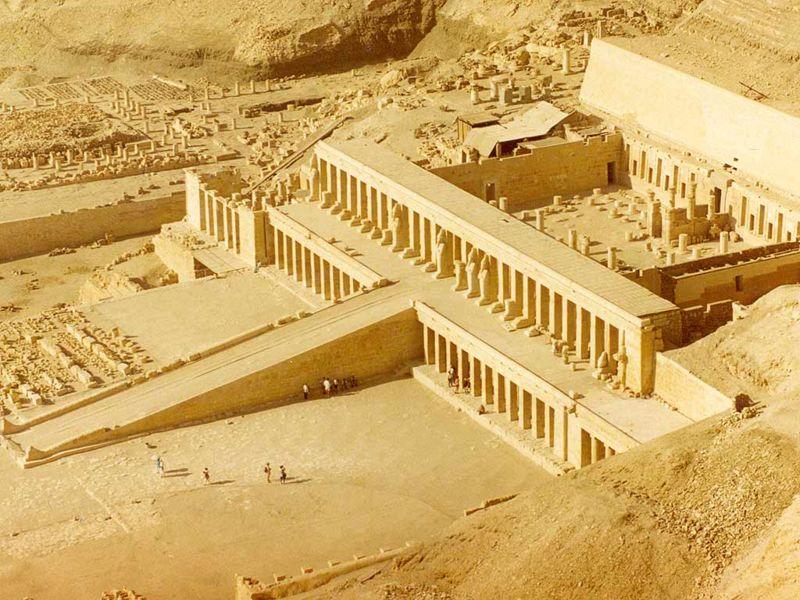

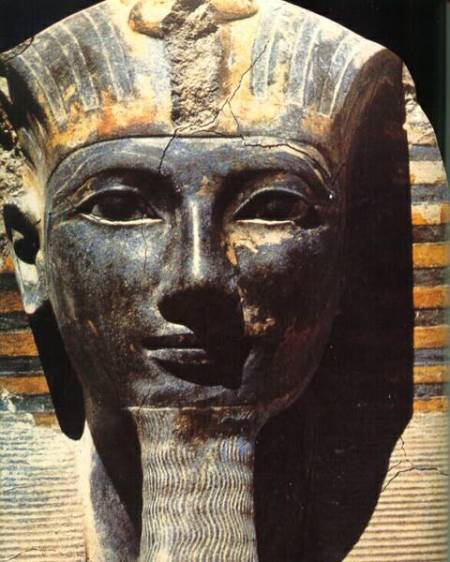

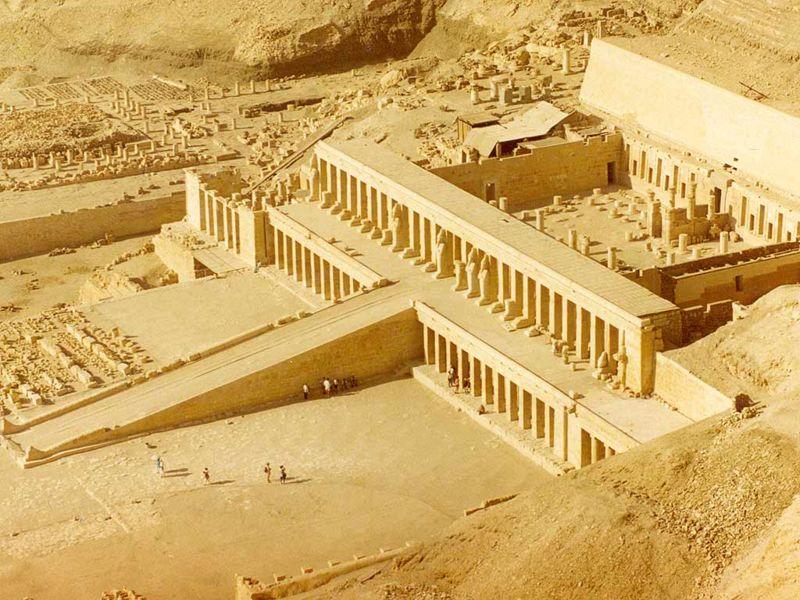

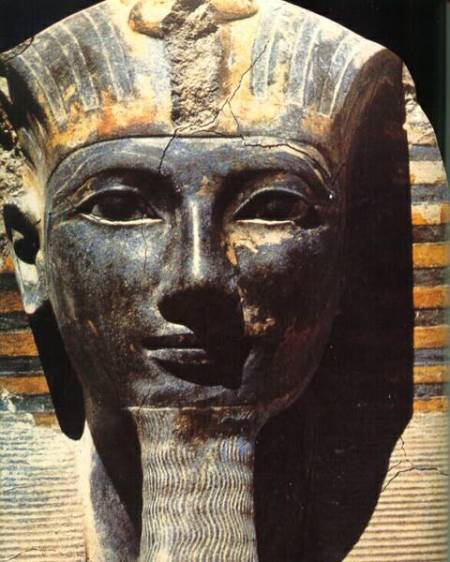

Autopsy of Another Collapse: New Kingdom Egypt A second historical example better illuminates the socioeconomic components and processes of national failure, with the important benefit of specific economic records. Under the 20th Dynasty (∼1187–1064 BCE) (27, 28), Egypt devolved from a powerful state to a divided nation in which authority had been usurped by a high priesthood that controlled the well- endowed temples as well as military forces, ready to engage in civil war. However, instead of recovery, Egypt came to be ruled by foreign dynasties. When Did Decline Begin? The pharaoh Merenptah shipped a great amount of grain to alleviate famine in the wavering Hittite empire at approximately 1210 BCE, suggesting a major drought in Anatolia but food abundance in the Nile Valley. Then, in 1207, he had to fend off a determined invasion of Libyans in alliance with several “Sea Peoples,” perhaps mobilized by the same environmental crisis in western Anatolia and the Aegean world. Three further foreign onslaughts confronted Ramesses III (1185–1153 BCE) of the 20th dynasty. He managed to defeat the fleet of Sea Peoples amid the Delta marshes in 1174. However, these powerful raiders had already destroyed all other states of the eastern Mediterranean, including Egyptian hegemony in the Levant, to terminate traditional commercial relationships, with implications for widespread economic depression (26). Although Ramesses III still carried out a major building program and sent an expedition to Punt, he made an unusual offering to the Nile in 1179, to propitiate the river and seek good floods (29). High-level malfeasance and corruption surfaced in 1157, and the king was victim to a harem conspiracy at the time of his death.  The severity of gathering economic problems can be gauged by unprecedented strikes and rioting, because of insufficient food and unpaid wages for the royal artisans (in 1156). The vizier could turn up only half the wheat needed, because the temple storage facilities were empty. The food supply had failed, the king's authority was brazenly challenged, and Egypt was patently in decline. Process of Devolution. On the accession of the king's son (Ramesses IV) (30), the royal workmen were paid off with food and silver, not by the king's treasury but by representatives of the High Priest (ref. 28, p. 607). Conflict between institutions is implied. Rolling food shortfalls continued, with runaway inflation. Grain prices, with respect to nonfood products, had begun to increase in 1170, eventually increasing to eight times and occasionally 24 times the standard price. Inflation peaked at approximately 1130, stabilizing at approximately 1110, with food prices falling rapidly at approximately 1100 to 1070 (31). This was the first subsistence crisis actually recorded in accounting books (∼1170–1110 BCE). Hardship was exacerbated by insecurity caused by Libyan marauders (1117–1101), favoring rural flight and declining productivity.  Royal power and prestige were fading. Rock for monumental construction was no longer quarried after 1151, and an 1135 expedition to the turquoise mines of Sinai was the last. A new High Priest had himself represented the same size as the king (∼1113), suggesting a more direct appropriation of power. Looting of the royal and private tombs at Thebes was underway with high-level complicity, and became scandalous under Ramesses XI (1099–1069 BCE), who did not use his completed tomb in the Valley of the Kings, and apparently chose to be buried in northern Egypt. This last monarch attempted to avoid the inevitable, calling in the Egyptian viceroy from Nubia, who battled the High Priest's army and, interestingly, assumed the notable title Overseer of the Royal Granaries (1086 BCE), while controlling southern Egypt for a decade. Thereafter, a new High Priest disenfranchised the pharaoh as the provider of life and safeguard of the cosmic order, declaring him a simple agent of the supreme god Amun (32). By 1075, Ramesses XI was a mere figurehead, residing in the Delta, with Upper Egypt ruled by the High Priest in the name of Amun, while Nubia became independent. Usurpation had been completed and Egypt was divided. Evaluation. The subsistence crises from 1170 to 1110 were preconditioned by (i) debilitating wars to repel invaders, (ii) the loss of Mediterranean commerce, (iii) official corruption, and (iv) a lack of support from the priesthood controlling the temple granaries. However, the repeated waves of wild inflation strongly suggest that famines were triggered by Nile failures (33). At Memphis, floods had declined by approximately 6 m from approximately 1300 to 1100 BCE, a trend that was paralleled in Nubia, where sand dunes swept the floodplain and agriculture had to be abandoned (22).  However, decline of the redistributive economy continued even after the famines were overcome, while Egypt was divided as a state and fragmented as a country. Unlike the admonitions literature of the First Intermediate Period, which espoused a return to traditional cosmic values, during the 20th Dynasty, there was no persuasive exhortation toward a moral high ground (18). Instead there is the “Tale of Woe,” which laments arbitrary rule, violence, excessive tax demands, falsified units of measure, hunger, and the breakdown of the social contract (ref. 34 and ref. 18. pp. 291–293). Egypt was impoverished and demoralized, and at the end of the new kingdom, swelling disaster did not provoke political or social resilience. Instead the ascendant military–priestly caste exhibited little vision. The once integrative national bureaucracy had failed amid pervasive corruption, giving way to a chaotic and superstition-driven theocracy that paraded as a “rebirth.” Nubian and Libyan dynasties followed in control. There was, in fact, no reconstitution or significant restoration until the indigenous Saite revival, which began under a vigorous king in 664 BCE, almost a half millennium after initial disintegration. The end of new kingdom Egypt was a quite different experience than old kingdom collapse, with breaching of multiple thresholds that apparently created virtually irreversible changes. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Dec 16, 2014 14:52:24 GMT

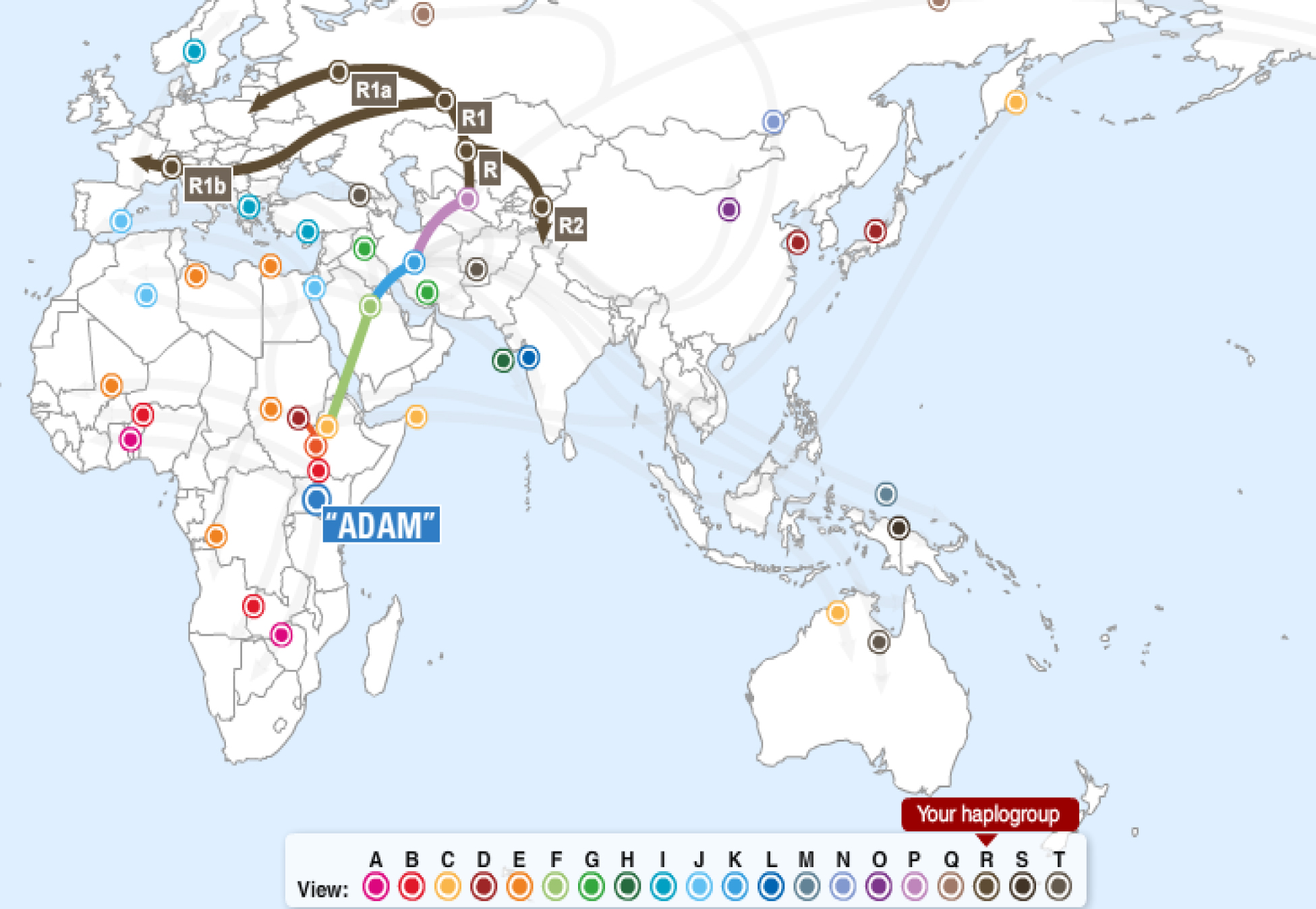

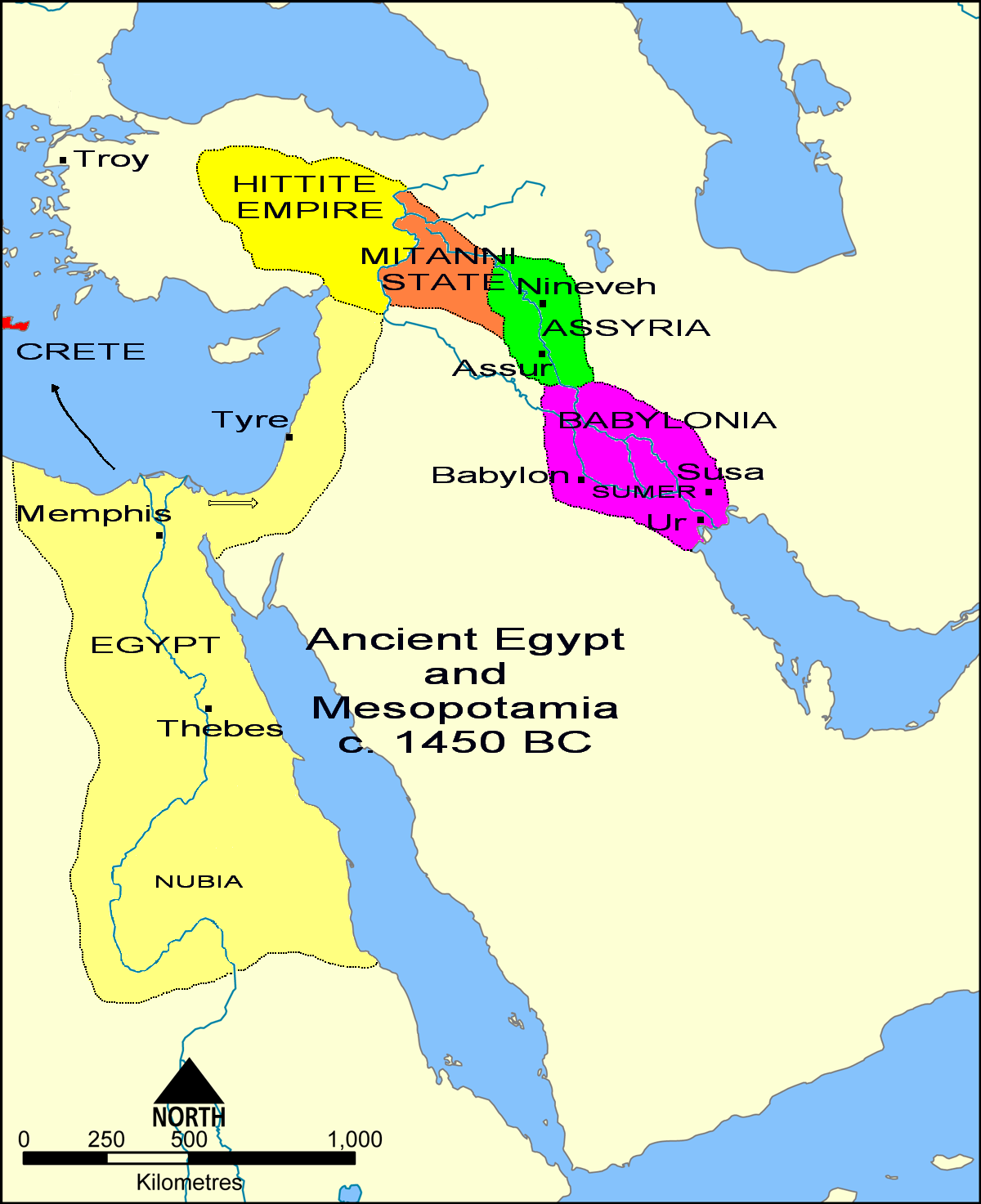

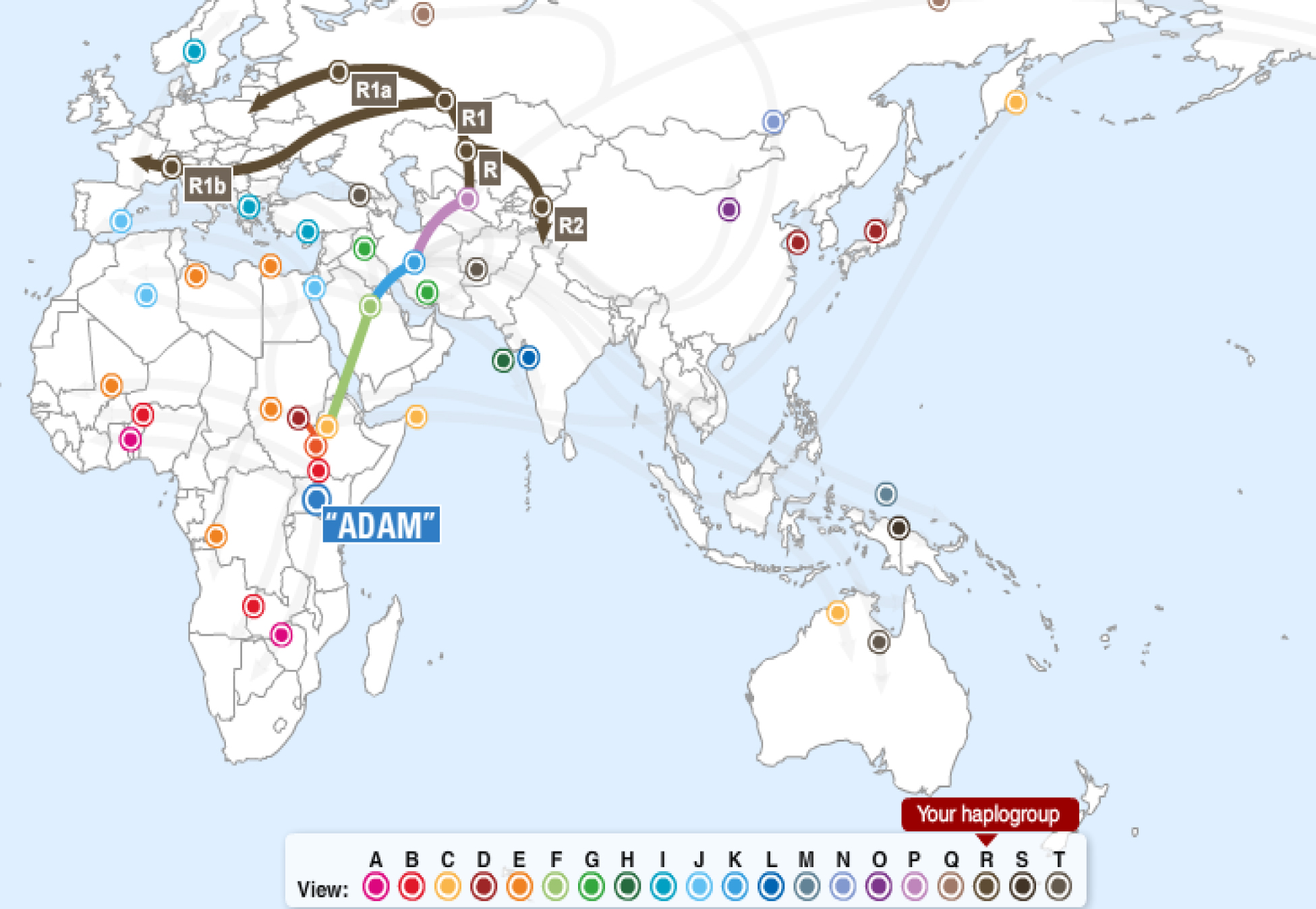

The M2 lineage is mainly found primarily in ‘‘Eastern,’’ ‘‘sub-Saharan,’’ and sub-equatorial African groups, those with the highest frequency of the ‘‘Broad’’ trend physiognomy, but found also in notable frequencies in Nubia and Upper Egypt, as indicated by the RFLP TaqI 49a, f variant IV (see Lucotte and Mercier, 2003; Al-Zahery et al. 2003 for equivalences of markers), which is affiliated with it. Results show that out of three Egyptian triad M78, M35 and M2, Y-chromosome M78 has the Highest frequency in Northern lower Egypt @ 51.9%. M35 has the slight Highest frequency in Southern Upper Egypt @ 28.8%. M2 has the Highest frequency in Northern and Southern Nubia @ 39.1%. M2 is virtually absent in North Africa’s lower Egypt at 1.2% and grows to a higher frequency traveling south-bound towards Upper Egypt and Nile valley’s Nubia.  Haplogroup M2 also coincides with Egyptian/Nubian Halfan Culture 24,000 B.C. The Halfan people, of Egypt and Nubia flourished between 18,000 and 15,000 BC in Nubia and Egypt. One Halfan site is dated, before 24,000 BC. M2- (20,000-30,000 B.P.). M35- (22,400 B.P.). M78- (18,600 B.P.). This would also give the plausible assignment of the Nubian-M2 and the Ethiopian PN2 (35,000 B.P.) as the “Progenitors” of “Nubian-Egyptian/Halfan Culture”.They lived on a diet of large herd animals and the Khormusan tradition of fishing. Although there are only a few Halfan sites and they are small in size, there is a greater concentration of artifacts, indicating that this was not a people bound to seasonal wandering, but one that had settled, at least for a time. The Halfan is seen as the parent culture of the Ibero-Maurusian industry which spread across the Sahara and into Spain. Sometimes seen as a Proto-Afro-Asiatic culture, this group is derived from “The Nile River Valley culture known as Halfan”, dating to about 17,000 BC. The Halfan culture was derived in turn from the Khormusan, which depended on specialized hunting, fishing, and collecting techniques for survival… Ramesses III According to a genetic study in December 2012, Ramesses III, second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty and considered to be the Last Great New Kingdom king to wield any substantial authority over Egypt, belonged to Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a/M2/E-V38, mainly found in North Africa, East Africa and Sub-saharan Africa. A genetic kinship analysis was done to investigate a possible family relationship between Ramesses III and Unknown man E, Who may actually be his son Pentawer. An ancient Egyptian Prince of the 20th dynasty, and son of Pharaoh Ramesses III and a secondary wife, Tiye. They amplified 16 Y-chromosomal, short tandem repeats (AmpF\STR yfiler PCR amplification kit; Applied Biosystems). Eight polymorphic microsatellites of the nuclear genome were also amplified (Identifiler and AmpF\STR Minifiler kits; Applied Biosystems). The Y-chromosomal Haplogroups of Ramesses III and unknown man E was screened using the Whit Athey’s Haplogroup Predictor we determined the Y-chromosomal Haplogroup E1b1a. The testing of polymorphic autosomal micro satellite loci provided similar results in at least one allele of each marker (table 2⇓). Although the mummy of Ramesses III’s wife Tiy was not available for testing, the identical Ychromosomal DNA and Autosomal half allele sharing of the two male mummies strongly suggest a Father-Son relationship.  The Afri-Asiatic Haplogroup R* and family also have percentages from 3%-6.8%. ( R*, R1a1 and R1b ) in lower and Upper Egypt combined 12.9%, and is virtually absent in Nile valley’s Nubia 0.0%. Which is in contrast of the Yemen and West Asia frequencies 10% or higher. Southern Egyptians Y Chromomses are mainly native to Africa, both sub and supra Saharan. This makes a grand total of 80.3% definitively African non-Arab ancestry in the upper Egypt region. Y-chromosomes possibly attributable to Arabmales are very much in the minority in this area. A rough estimate (since no women invaded Egypt) is that about 5% or less of this population are from Non Dynastic Egyptian peoples, and not all of these would be Arabs. Although Haplogroup R1* has an African-Asiatic Origin and Migration, It has Notable frequencies through out Africa as well.. Haplogroup R1*-M173 is the pristine form of Haplogroup R. In Africa researchers have detected frequencies as high as 95% among Sub-Saharan Africans. The phylogenetic profile of R-M173 supports an ancient migration of Kushites from Africa to Eurasia as suggested by the Classical Writers. In Fig. 3, we outline the spread of Haplogroup R from Nubia into Asia and West Africa. This Expansion of an African Kushite population probably took place Neolithic period. The Accumulated Classical literature, Archaeological, Craniometric, Genetic and Linguistic evidence suggest a Genetic relationship between the Kushites of Africa and Kushites in Eurasia that cannot be explained by Micro Evolutionary Mechanisms. The phylogeographic profile of R1*-M173 supports this Ancient Migration of Kushites fromAfrica to Eurasia as suggested by the Classical writers. This expansion of Kushites into Eurasia probably took place over 4kya. The present studies on Y-chromosomes M78 , M35 , M2 shows the Egyptian Dynasties has Northern and Southern inhabitants.  The migration difference from North to South mimics the Nubia, Upper Egypt and lower Egypt Kingdoms of ancient times. While Kashta of the 25th dynasty ruled Nubia from Napata, which is 400 km north of Khartoum, the modern capital of Sudan, He also exercised a strong degree of control–over Upper Egypt by managing to install his daughter,Amenirdis I, as the presumptive God’s Wife of Amun in Thebes in line to succeed the serving Divine Adoratrice of Amun,Shepenupet I, Osorkon III’s Daughter. This Development was “the Key moment in the process of the extension of Kushite power over Egyptian territories” under Kashta’s rule since it officially legitimized the Kushite takeover of the Thebaid region. The Hungarian Kushite scholar László Török notes that there were probably already Kushite garrisons stationed in Thebes itself during Kashta’s reign both to protect this king’s authority over Upper Egypt and to thwart a possible future invasion of this region from Lower Egypt. |

|