|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 6, 2015 20:21:43 GMT

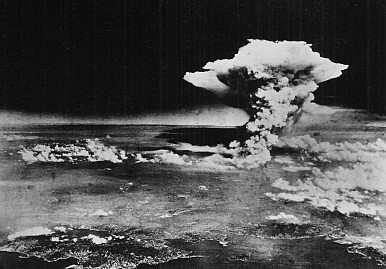

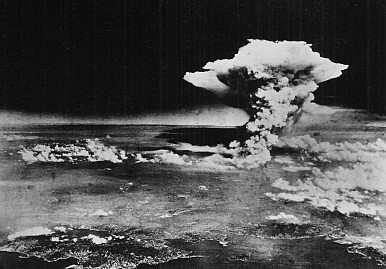

U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s decision to use nuclear weapons against the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki stands as one of the most consequential uses of weaponry in human history, a watershed moment in the twilight days of World War II, and a perennial question of moral and strategic ambiguity. In fact, all contemporary conversations about the dangers of nuclear weapons and their proliferation inevitably evoke their two uses in wartime on August 6 and August 9, 1945.  What is commonly overlooked, however—and I don’t put this forward as an attempt at revising history—is the influence the bombings themselves actually had on Japan’s decision to surrender on August 15. Indeed, the conventional understanding of the use of the bombs is that they shocked the Japanese leadership so much that they could not help but surrender in the face the awesome might of these new weapons. Those who argue in favor of Truman’s decision to use the bomb build off this to note that countless lives—Japanese and Americans—were saved by the fact that Allied forces did not proceed with Operation Downfall, the planned amphibious invasion of Japan, which in some estimates would have cost millions of lives for the Allies and tens of millions for the Japanese.  But based on what evidence we have of what Japanese leaders were writing and thinking at the time, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not a threshold event for convincing Imperial Japan to acquiesce to unconditional surrender. This is important because on a very fundamental level, the hallowed place nuclear weapons occupy in our contemporary security discourse is based on their ability to deter conflict and encourage compliance — it is assumed that these weapons work like no other. For Imperial Japan, the late spring and early summer of 1945 were already hellish. The Imperial Japanese Army suffered catastrophic losses at Iwo Jima and Okinawa; Tokyo, along with over 60 other Japanese cities, was bombed with incendiary explosives. In the case of the latter, civilian deaths were comparable to the death toll at Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the fire-bombings of Tokyo are thought to have claimed over 100,000 lives while Hiroshima and Nagasaki resulted in 120,000 and 80,000 civilian deaths respectively).  Despite the combined carnage of weeks of incendiary bombing, which reduced Japanese cities to ash, and the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan’s leaders at the time appeared undeterred. Korechika Anami, the Japanese minister of war at the time, noted that the atomic bombings were ”no more menacing than the firebombing” that came before them. Toroshiro Kawabe, deputy chief of staff of the Imperial Japanese Army, remarked that while the nuclear weapons caused a “serious stimulus (shock or jolt),” Japan “must be tenacious and fight on.” Kawabe’s dairy contains another entry on August 9, 1945–the day Nagasaki was bombed–that “The Soviets have finally risen!” With the entry of the Soviet Union into the war, Japanese military leaders immediately convened to declare martial law and raised the possibility of instituting all-out military rule over Japan, supplanting the civilian leadership. In essence, for these Japanese military planners, the fact that Stalin’s Soviet Union had joined the campaign was a more significant strategic event than the bombings themselves. Even after Hiroshima had been flattened, Japanese soldiers stood prepared on the shores on Honshu, Kyushu, and Hokkaido for the impending amphibious assault. For them, the fight hadn’t ended. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 7, 2015 20:24:13 GMT

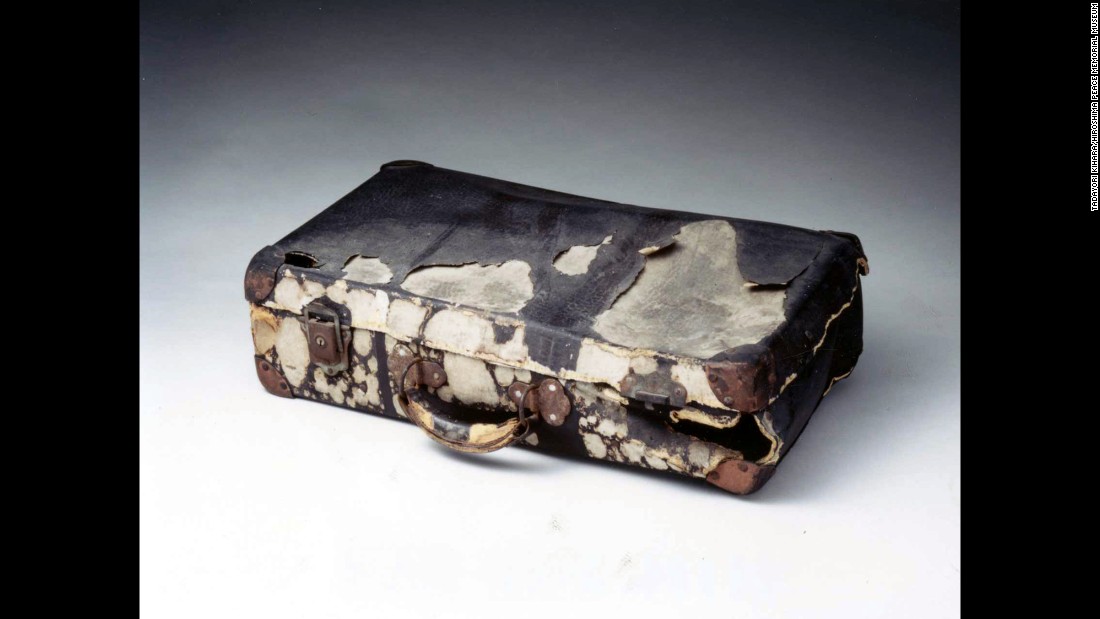

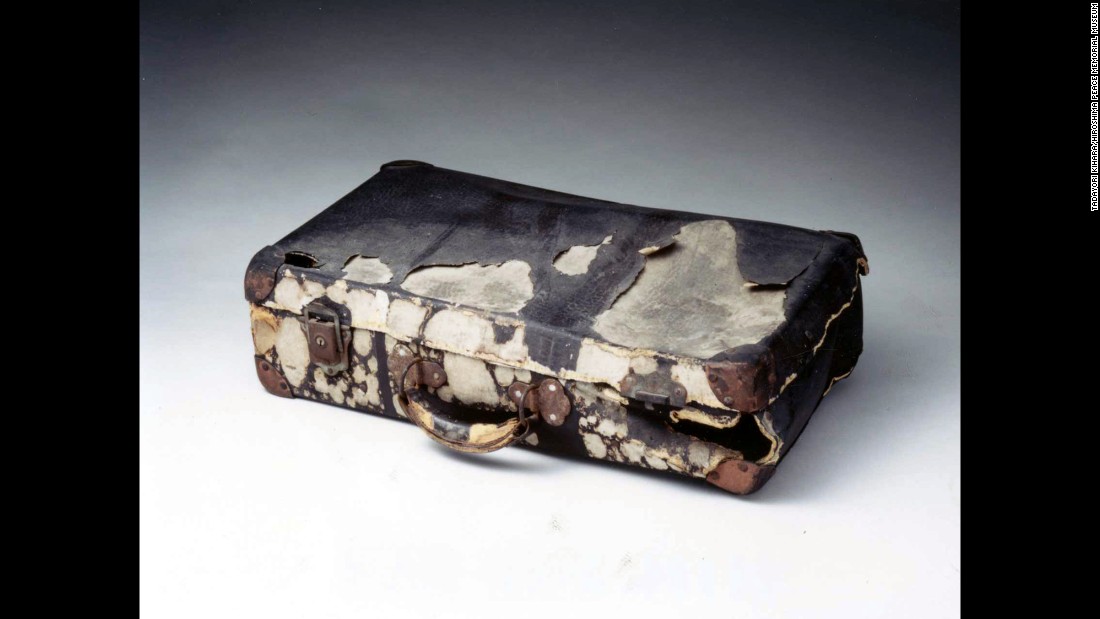

A battered tricycle. Melted coins. A shredded shirt. Seventy years have passed, but artifacts and survivors still provide tangible links to the world's first act of nuclear warfare. The world still struggles to fully understand the hellish events in Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945, after a U.S. warplane dropped the most powerful weapon ever produced on military targets and unsuspecting civilians.  Those who survived say it started with a brilliant, noiseless flash. They remember a massive wave of intense heat that turned clothing to rags. People closest to the bomb were immediately vaporized or burned to ashes. There was a deafening boom and a blast that -- for some -- felt like being stabbed by hundreds of needles.  Then the fires started. Tornadoes of flames swept through the city. Many survivors found themselves covered with blisters. Bodies littered the streets. It got worse. It began to rain. Sticky, radioactive raindrops blackened everything they touched and were hard to wash off.  It's estimated that at least 70,000 people died in the hours immediately following the blast. Later, radiation sickness, cancer and other long-term effects pushed the estimated death toll above 200,000, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.  But many survived and are still alive today. As of March 2014, Japan counted 192,719 people as registered survivors, according to the news network Asahi. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum has collected thousands of survivors' stories and their drawings, along with artifacts from the blast.  The drawings depict haunting memories. In one drawing, a mother is screaming her child's name while looking down at a river full of dead children. Another rendering shows a pair of students with swollen blue faces. An exodus of wounded survivors is depicted in another drawing. They're seen packed into rail cars like cattle.  Each drawing reveals glimpses of that horrific day, reflected through the prism of a survivor's personal struggle to stay alive.  |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 8, 2015 20:21:09 GMT

Fewer Americans than at any time since 1945 believe that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima 70 years ago today and Nagasaki three days later was a good idea. In a YouGov poll just published, 45 per cent of respondents between the ages of 18 and 29 said that president Truman had made the wrong decision, against 41 per cent who approved. The margin was slightly narrower among 30 to 44-year- olds – 36 per cent to 33.  Respondents between 45 and 65 supported the bombing, 55 per cent to 21 per cent. Over-65s backed Truman 65 to 15 per cent. Among the population as a whole, 45 per cent were in favour of the bombing, 29 per cent against. The figures can tellingly be compared with Gallup results in August 1945 suggesting that 85 per cent of Americans were content with the bombing, only 10 per cent opposed. (In the same poll, a remarkable 23 per cent said that they wished that more atomic bombs had been dropped before the Japanese had had a chance to surrender.)  In a radio broadcast within hours of Hiroshima, Truman told the nation: “We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have standing above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no doubt.” (Docks, factories, communications. . . People didn’t rate a mention.) Days later, of course, Truman made good on his threat. One of the first doctors to arrive in Hiroshima after the blast told: “Tremendous numbers of unidentified corpses were piled up and cremated on the spot. The injured and irradiated continued to die. Day and night in every corner of the city, corpses are piled upon the corpses and burned.”  It wasn’t until the Australian Wilfred Burchett arrived as the first journalist to make it to Hiroshima that the aftermath of the explosion was described to a western audience: “I write this as warning to the world,” was his intro on page one of the Daily Express. He described in detail how he had walked through a hospital ward packed with people with their skin hanging in flaps from their bodies, eyes opaque, dying, but with no visible marks. There being no word for it yet, he wrote of “an atomic plague.” In retaliation for telling it as he had seen it, his press accreditation was famously withdrawn. He was vilified for years. In some circles he still is. The US strategic bombing survey, commissioned by Truman, compiled by a civilian team including John K Galbraith and based on interviews with more than 400 US officers and on access to the complete Japanese military logs, reported in July 1946: “Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the survey’s opinion that . . . Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.” The Soviet Union joined the war in Asia two days after Hiroshima, a day before Nagasaki, delivering in the nick of time on a promise made by Stalin in Yalta – and also with a view to qualifying as a combatant entitled to a share of the spoils. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 10, 2015 2:18:03 GMT

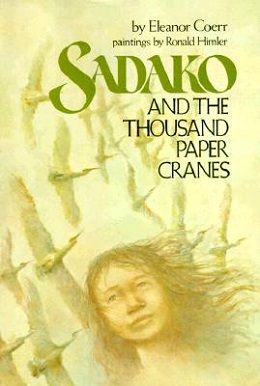

The comment was made by Clifton Truman Daniel, 58, as he spoke to U.S. high-school students at an event organized to discuss war and peace in New York City in April. His grandfather was former U.S. President Harry Truman, who decided to use atomic bombs toward the end of World War II. The friends he was referring to are the victims of the bombing. “And that’s where I stand today, right in the middle,” Daniel said.  U.S. efforts to develop atomic bombs shifted into high gear in April 1942. On July 25, 1945, an order was issued, with Truman’s approval, for atomic bombs to be dropped. It is said that the U.S. sought to end the war on the strength of the overwhelming power of atomic bombs. Daniel never heard anything about the atomic bombings from his grandfather.  While working as a reporter with a North Carolina newspaper 21 years ago, he was assigned to gather news on a Japanese high-school student studying at a local school. Her host father said to Daniel: “I told her who your grandfather was. Her grandfather was killed in Hiroshima.” Before meeting her, Daniel told himself he would have to endure the criticism he was sure he would receive. Upon meeting her, he said, “I’m so sorry.” However, she responded with a smile, saying, “Thank you.” He wondered why she did not get angry or blame him.  After meeting the Japanese student, Daniel began to think he should explore two fundamental questions: why his grandfather decided to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and what effect they had on the two cities. Emi Okada, 78, from Hiroshima, is a survivor of the atomic bombing of the city. She was 8 years old when she was exposed to radiation from the bomb. In August 2012, Okada met Daniel during his first visit to the city. For about an hour, Okada gave him an account of what had happened to her on Aug. 6, 1945, and beyond. Okada was hit by a blast about 1.7 miles from the epicenter. She stepped across many dead bodies to escape. The scene of the city ablaze persists in her memory, and that is why she still dislikes the sunset, she said. She lost her 12-year-old sister.  Daniel filmed oral testimony from about 20 A-bomb victims, and the video footage was given to the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Missouri. A film of the testimony is planned to be shown at the facility. “The only thing that survivors asked me to do was to help keep telling their stories so we don’t have another nuclear war,” Daniel said. “That’s what I’ve tried to do. Keep telling their stories." |

|