Post by Admin on Jun 1, 2022 17:49:59 GMT

Discussion

Despite intensive progress in genomic studies of ancient European populations, our knowledge on demographic processes that occurred in the Central-Eastern part of the continent after the Neolithic is still very limited. Until recently, there were no data describing the genetic makeup of people living in Central Europe east of the Oder River during the BA and IA. Archaeological and genomic findings suggested that on the turn of the LN and BA this region (contemporary Poland) was influenced by four major cultures: BBC, CWC, UC and YAM (Fig. 1a). However, due to the lack of reliable data, the actual range of these cultures, and consequently, the placement of the borders between them, as well as the later history of these populations, are difficult to determine.

To extend our knowledge on the issues described above, we initiated broad genetic studies of the populations inhabiting the territory of present-day Poland in the IA. In our earlier paper, we characterized the maternal genetic makeup of the individuals living in the west part of contemporary Poland8. In this report, we focused on the maternal genetic history of the Mas-VBIA group that lived in the eastern part of contemporary Poland (the region located between the Vistula and Bug Rivers) during the 2nd to 4th century A.D. We found that the intrapopulation diversity of the Mas-VBIA (π = 0.016263) was beyond expectations. It was as high, as is currently observed for Asian populations (π between 0.013 and 0.017), and exceeded the values typical for non-isolated European populations (π between 0.006 and 0.01), as well as the intrapopulation diversity previously determined for its western counterpart – the Kow-OVIA (π = 0.0079). However, it should be noted here that due to the postmortem DNA damage, the diversity estimates could be inflated. Accordingly, one can hypothesize that people living between the Vistula and Bug Rivers in the IA formed genetically diversified, non-isolated populations. The haplogroup frequencies observed for the Mas-VBIA were similar to those reported for the Kow-OVIA. Haplogroup H frequency was intermediate between CWC and BBC and lower than in CEM. Interestingly, the frequencies of the mtDNA haplogroups U5a (characteristic for Eastern Hunter Gatherer groups) and U5b (characteristic for Western Hunter Gatherer groups) were a significantly different in the Mas-VBIA and other IA populations studied so far (the JIA and Kow-OVIA). The Mas-VBIA was characterized by the absence of mtDNA haplogroup U5b and the high frequency of mtDNA haplogroup U5a (14.8%), whereas in the JIA and Kow-OVIA, mtDNA haplogroup U5b was more prevalent than U5a. As noticed previously8, the domination of U5b over U5a in Central Europe was observed only during the IA. Therefore, either the process that led to the temporal increase of U5b mtDNA haplogroup frequency did not affect regions east of Vistula, or its effects were subsequently removed by another demographic event.

All high dimensional analyses of genetic diversity (PCA, hierarchical clustering, MDS) within the Mas-VBIA and other ancient and extant populations were consistent and showed that the Mas-VBIA was closely connected with the Kow-OVIA and had a similar genetic structure to that of Central European LN/EBA populations. Within the group of three IA Central European populations, the Mas-VBIA was the closest related with the Kow-OVIA, and the distance between the JIA and Mas-VBIA was shorter than that between the JIA and Kow-OVIA. Furthermore, the Mas-VBIA had close genetic connections with the YAM, located in the eastern parts of Europe. We did not observe these connections in either the Kow-OVIA or the JIA. Earlier, Haak et al.32 showed that there are clear genetic links, even at the mtDNA level, between the central European CWC and BBC populations and the YAM. However, if close genetic connections between the Mas-VBIA and YAM were a result of the LN migratory events, the same should be observed in the remaining IA populations of the region. Therefore, we propose that the presence of the Pontic-Caspian steppe genetic component in the Mas-VBIA is a result of the migratory event or events that occurred in the IA period. Considering the high prevalence of the mtDNA haplogroup U5a in the Mas-VBIA, one can hypothesize that the direction of this movement was from east to west.

Another interesting observation was the genetic proximity between the BEC and virtually all subsequent populations (the CWC, BBC, UC, JIA, Kow-OVIA and Mas-VBIA). This proximity was most evident when shared mtDNA haplotypes were analyzed. We found that the haplotypes shared between all LN and IA populations were nearly always present in the BEC. The BEC is part of a TRB cultural horizon that spread from North to Central Europe during the MN in the form of the sequence of Danubian populations14. Thus, here we provide an additional line of evidence that Danubian Neolithic populations were a common genetic background of all Central-North and Central-East populations in Europe.

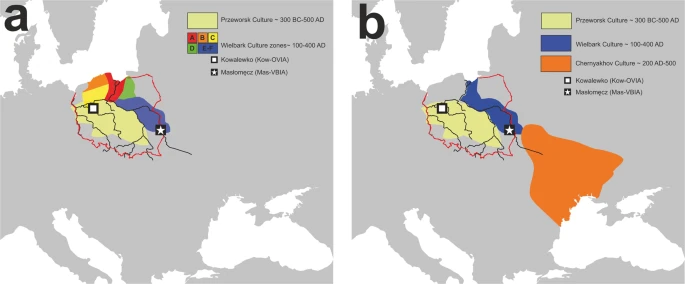

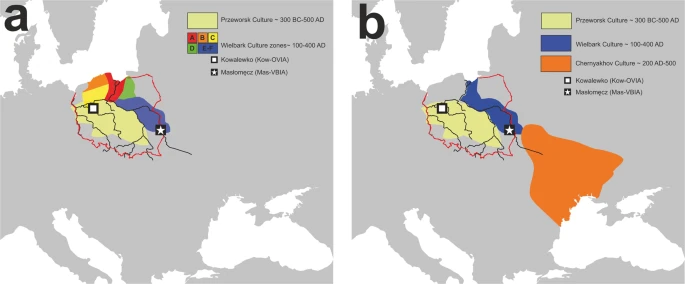

There are two major historical narratives describing the formation of the Wielbark culture. The first one links its development with Goth migrations33, and the second, with the spread of the local Oksywie culture that appeared at the Baltic seashore at approximately the 2nd century B.C20,34. In addition, there are at least two hypotheses concerning the origin of Goths. One of them assumes that the homeland of the Goths was located in the southernmost part of the Germanic territories other than in Scandinavia35. Considering the results obtained for both the Kow-OVIA and Mas-VBIA, one can assume that they are, to a large extent, consistent with the postulated chronology of early migrations of Goths and their settlement in Central-East Europe. The high genetic diversity of the Mas-VBIA strongly corresponds with the suggested role of Masłomęcz at that time22. The archaeological findings indicate that in the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., it was one of the major cultural and political Goth centers. In addition, the genetic relationships reported here between the Mas-VBIA and both earlier characterized IA populations (the Kow-OVIA and JIA) support the opinion that southern Scandinavia was the homeland of the Goths. According to some authors, the process of their migration through the contemporary territory of Poland, which was connected with the spread of the Wielbark culture, can be divided into the following 6 stages, named with the letters A-F (for details, see Fig. 7a)20. In the first stage, the Goths colonized the mouth of the Vistula River during the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. (stage A). Then, they spread west along the Baltic seashore (stage B). In stage C, the Goths moved south and ousted the Przeworsk culture from the northwest part of contemporary Poland, including Kowalewko (1st and 2nd centuries A.D.). The Goth’s settlements established in this area could have a rather temporal character suggested by the fact that the genetic structure of the Kow-OVIA population was biased by sex. Males from the Kow-OVIA were closely related with the JIA and females with Neolithic farmers8 (most likely they represented the local population related with the Przeworsk culture). During the next stage (D), the Goths spread east of the Vistula, and then they migrated along the Vistula and Bug Rivers towards the Black See and established the Chernyakhov culture by mixing with Pontic–Caspian steppe populations (stage E). Finally, a part of the Chernyakhov culture population moved back and established a large settlement near Masłomęcz called the “Masłomęcz group” (stage F, 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D.) (Fig. 7b). Such a scenario explains a large part of our findings well, including (i) the high prevalence of the mtDNA U5a haplogroup (characteristic for the eastern parts of Europe); (ii) the close genetic distance to the YAM observed for the Mas-VBIA and the lack of these characteristics in the cases of the Kow-OVIA and JIA; and (iii) the high genetic diversity of the Mas-VBIA. The latter indicates that the “Masłomęcz group”, often considered the Goths, from a genetic standpoint, was a mixture of different populations. Unfortunately, the presented data cannot unequivocally verify both hypotheses on the Goth origin and their relationships with the Oksywie culture. Thus, we still do not know whether the Goths replaced the Oksywie culture or induced its formation. It is also possible that all the scenarios presented here contain some truth and describe different periods of the Goth population development and migrations. Thus, further studies are necessary to verify them.

Figure 7

Supplementary information

Despite intensive progress in genomic studies of ancient European populations, our knowledge on demographic processes that occurred in the Central-Eastern part of the continent after the Neolithic is still very limited. Until recently, there were no data describing the genetic makeup of people living in Central Europe east of the Oder River during the BA and IA. Archaeological and genomic findings suggested that on the turn of the LN and BA this region (contemporary Poland) was influenced by four major cultures: BBC, CWC, UC and YAM (Fig. 1a). However, due to the lack of reliable data, the actual range of these cultures, and consequently, the placement of the borders between them, as well as the later history of these populations, are difficult to determine.

To extend our knowledge on the issues described above, we initiated broad genetic studies of the populations inhabiting the territory of present-day Poland in the IA. In our earlier paper, we characterized the maternal genetic makeup of the individuals living in the west part of contemporary Poland8. In this report, we focused on the maternal genetic history of the Mas-VBIA group that lived in the eastern part of contemporary Poland (the region located between the Vistula and Bug Rivers) during the 2nd to 4th century A.D. We found that the intrapopulation diversity of the Mas-VBIA (π = 0.016263) was beyond expectations. It was as high, as is currently observed for Asian populations (π between 0.013 and 0.017), and exceeded the values typical for non-isolated European populations (π between 0.006 and 0.01), as well as the intrapopulation diversity previously determined for its western counterpart – the Kow-OVIA (π = 0.0079). However, it should be noted here that due to the postmortem DNA damage, the diversity estimates could be inflated. Accordingly, one can hypothesize that people living between the Vistula and Bug Rivers in the IA formed genetically diversified, non-isolated populations. The haplogroup frequencies observed for the Mas-VBIA were similar to those reported for the Kow-OVIA. Haplogroup H frequency was intermediate between CWC and BBC and lower than in CEM. Interestingly, the frequencies of the mtDNA haplogroups U5a (characteristic for Eastern Hunter Gatherer groups) and U5b (characteristic for Western Hunter Gatherer groups) were a significantly different in the Mas-VBIA and other IA populations studied so far (the JIA and Kow-OVIA). The Mas-VBIA was characterized by the absence of mtDNA haplogroup U5b and the high frequency of mtDNA haplogroup U5a (14.8%), whereas in the JIA and Kow-OVIA, mtDNA haplogroup U5b was more prevalent than U5a. As noticed previously8, the domination of U5b over U5a in Central Europe was observed only during the IA. Therefore, either the process that led to the temporal increase of U5b mtDNA haplogroup frequency did not affect regions east of Vistula, or its effects were subsequently removed by another demographic event.

All high dimensional analyses of genetic diversity (PCA, hierarchical clustering, MDS) within the Mas-VBIA and other ancient and extant populations were consistent and showed that the Mas-VBIA was closely connected with the Kow-OVIA and had a similar genetic structure to that of Central European LN/EBA populations. Within the group of three IA Central European populations, the Mas-VBIA was the closest related with the Kow-OVIA, and the distance between the JIA and Mas-VBIA was shorter than that between the JIA and Kow-OVIA. Furthermore, the Mas-VBIA had close genetic connections with the YAM, located in the eastern parts of Europe. We did not observe these connections in either the Kow-OVIA or the JIA. Earlier, Haak et al.32 showed that there are clear genetic links, even at the mtDNA level, between the central European CWC and BBC populations and the YAM. However, if close genetic connections between the Mas-VBIA and YAM were a result of the LN migratory events, the same should be observed in the remaining IA populations of the region. Therefore, we propose that the presence of the Pontic-Caspian steppe genetic component in the Mas-VBIA is a result of the migratory event or events that occurred in the IA period. Considering the high prevalence of the mtDNA haplogroup U5a in the Mas-VBIA, one can hypothesize that the direction of this movement was from east to west.

Another interesting observation was the genetic proximity between the BEC and virtually all subsequent populations (the CWC, BBC, UC, JIA, Kow-OVIA and Mas-VBIA). This proximity was most evident when shared mtDNA haplotypes were analyzed. We found that the haplotypes shared between all LN and IA populations were nearly always present in the BEC. The BEC is part of a TRB cultural horizon that spread from North to Central Europe during the MN in the form of the sequence of Danubian populations14. Thus, here we provide an additional line of evidence that Danubian Neolithic populations were a common genetic background of all Central-North and Central-East populations in Europe.

There are two major historical narratives describing the formation of the Wielbark culture. The first one links its development with Goth migrations33, and the second, with the spread of the local Oksywie culture that appeared at the Baltic seashore at approximately the 2nd century B.C20,34. In addition, there are at least two hypotheses concerning the origin of Goths. One of them assumes that the homeland of the Goths was located in the southernmost part of the Germanic territories other than in Scandinavia35. Considering the results obtained for both the Kow-OVIA and Mas-VBIA, one can assume that they are, to a large extent, consistent with the postulated chronology of early migrations of Goths and their settlement in Central-East Europe. The high genetic diversity of the Mas-VBIA strongly corresponds with the suggested role of Masłomęcz at that time22. The archaeological findings indicate that in the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., it was one of the major cultural and political Goth centers. In addition, the genetic relationships reported here between the Mas-VBIA and both earlier characterized IA populations (the Kow-OVIA and JIA) support the opinion that southern Scandinavia was the homeland of the Goths. According to some authors, the process of their migration through the contemporary territory of Poland, which was connected with the spread of the Wielbark culture, can be divided into the following 6 stages, named with the letters A-F (for details, see Fig. 7a)20. In the first stage, the Goths colonized the mouth of the Vistula River during the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. (stage A). Then, they spread west along the Baltic seashore (stage B). In stage C, the Goths moved south and ousted the Przeworsk culture from the northwest part of contemporary Poland, including Kowalewko (1st and 2nd centuries A.D.). The Goth’s settlements established in this area could have a rather temporal character suggested by the fact that the genetic structure of the Kow-OVIA population was biased by sex. Males from the Kow-OVIA were closely related with the JIA and females with Neolithic farmers8 (most likely they represented the local population related with the Przeworsk culture). During the next stage (D), the Goths spread east of the Vistula, and then they migrated along the Vistula and Bug Rivers towards the Black See and established the Chernyakhov culture by mixing with Pontic–Caspian steppe populations (stage E). Finally, a part of the Chernyakhov culture population moved back and established a large settlement near Masłomęcz called the “Masłomęcz group” (stage F, 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D.) (Fig. 7b). Such a scenario explains a large part of our findings well, including (i) the high prevalence of the mtDNA U5a haplogroup (characteristic for the eastern parts of Europe); (ii) the close genetic distance to the YAM observed for the Mas-VBIA and the lack of these characteristics in the cases of the Kow-OVIA and JIA; and (iii) the high genetic diversity of the Mas-VBIA. The latter indicates that the “Masłomęcz group”, often considered the Goths, from a genetic standpoint, was a mixture of different populations. Unfortunately, the presented data cannot unequivocally verify both hypotheses on the Goth origin and their relationships with the Oksywie culture. Thus, we still do not know whether the Goths replaced the Oksywie culture or induced its formation. It is also possible that all the scenarios presented here contain some truth and describe different periods of the Goth population development and migrations. Thus, further studies are necessary to verify them.

Figure 7

Supplementary information