|

|

Post by Admin on Nov 9, 2015 9:51:59 GMT

The rumour had been circulating for years: Geert Wilders is an 'Indo' (an Indonesian-European, an ethnic mix that originated when the Dutch colonised Indonesia). In June a genealogist said he had found several Indonesian ancestors of the populist Dutch politician known for his rabid anti-immigrant and anti-Islam ideas. Now anthropologist Lizzy van Leeuwen describes how his roots can be seen as the driving force behind his outspoken views.  The 6-page article reveals that Wilders' grandmother, Johanna Ording-Meijer, came from an old Jewish-Indonesian family and that Wilders lied about this in his 2008 biography. However, Van Leeuwen, an expert on the position of Indo-Dutch people in the post-colonial age, goes beyond the notion that a politician known for judging others on their ethnic roots can himself be traced to foreign ancestors.  Van Leeuwen went into the national archives to find the sad story of Wilders' grandfather on his mother's side. Johan Ording was a regional financial administrator in the Dutch colony who suffered several bankruptcies and was fired while on leave in the Netherlands in 1934. He was reduced to begging when the government refused to give him a pension, but later made it to prison director. Van Leeuwen suggests that Wilders is out to avenge the injustice done to his grandfather.  But more than anything, he was defined by his Indo-roots, she says. Indonesia was a Dutch colony until 1949 and many mixed-race people moved to the Netherlands after the Indonesian independence. Van Leeuwen describes how these people were put in the same 'cultural minority' box with labour immigrants from Turkey and Morocco, whom they felt no connection to at all. More so, they had always felt very patriotic about the Netherlands and harboured strong sentiments against Islam, the dominant religion in their motherland. Van Leeuwen explains how this group has long been part of extreme-right movements (many supported the Dutch Nazi party NSB in Indonesia in the 1930s) while others belonged to the far-right of the right-wing liberal party VVD. She puts Wilders' statements in the conservative and colonial tradition of this group, which strongly believed in patriotism and "European values".  Van Leeuwen's analysis goes beyond the personal level: "The fact that Wilders obviously operates in a post-colonial political dimension, without it being recognised, says a lot about how the Netherlands dealt with, and still deals with the colonial past. Keep quiet, deny, forget and look the other way have been the motto for decades. Because of that, no one could imagine that what happened in Indonesia 50 years ago could still have its impact on modern-day politics." |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Nov 10, 2015 9:55:10 GMT

Nick Clegg’s mother has revealed the full extent of her ordeal in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp during the Second World War. In the past, the Deputy Prime Minister has spoken movingly of the bravery of 74-year-old Hermance Clegg, who was just six when sent to the camp in Indonesia – then called the Dutch East Indies. Now Mrs Clegg has spoken of her years of suffering in a candid interview with a Dutch magazine.  Mrs Clegg, who was held with her mother and two sisters while their father languished in another camp nearby, recalled women and children suffering savage beatings from Japanese soldiers, being forced to stand for hours in the blazing sun and having their heads shaved. She said they were regularly ordered to parade in line bowing in the direction of Japan. Those who did not bow deeply enough were viciously beaten. Internees were also being slowly starved to death. She said she became so thin that she was weeks, if not days, from death when the war ended.  Mrs Clegg was born in the Dutch East Indies in 1936 to Dutch oil executive Herman van den Wall Bake and his wife Louise. They lived a comfortable life until the outbreak of war. When the Japanese took control of the Dutch East Indies in 1942 her father, then 36 and known as Hemmy, was arrested and put into the Glodok PoW camp in Batavia, the former name of the Indonesian capital Jakarta. His 31-year-old wife and daughters, then aged ten, six and four, initially stayed at the house of a friend nearby, but they were forcibly moved to a camp for women and children called Kramat, where food was desperately short. Mrs Clegg told the magazine that while the family was being evicted, one of the Japanese soldiers kicked her mother so hard on the shin that she developed an ulcer that did not heal until the war was over.  But despite the hardship, her mother tried her best to educate her three daughters. 'She gave me a dictionary she had compiled for my birthday,’ said Mrs Clegg. ‘She read Alice In Wonderland in English with my sister. ‘Because she did not know enough about mathematics, she paid for my elder sister’s maths lesson [taught by another internee] with baked sago starch, even if it meant the four of us went hungry.’ Hunger was a daily part of life in the camp and by the time the prisoners were liberated in 1945, Mrs Clegg’s mother’s weight had dropped to five and a half stone. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Dec 5, 2016 20:31:03 GMT

Dutch secret services conducted an investigation into suspicions that Geert Wilders, head of the anti-Islam Party for Freedom, was strongly influenced by top Israeli military and political figures, according to reports in the Netherlands. Wilders, the firebrand leader of the Dutch far-right Party for Freedom (PVV), was investigated by the country’s General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) between 2009 and 2010 over his “ties to Israel and their possible influence on his loyalty,” according to De Volkskrant newspaper, which conducted interviews with 37 public officials and former intelligence officers. An investigation into an opposition leader is an exceptional case in the Netherlands, the newspaper noted, citing several former intelligence officers who said such inquiries are considered an “absolute no-go” due to political sensitivity. The intelligence agency sanctioned the operation, citing concerns about “the possibility that Wilders is influenced by Israeli factors,” according to the newspaper. Back in 2010, Wilders reportedly had close ties to influential people in Tel Aviv. At the time, he visited Major General Amos Gilad, former chief of the Israeli Defense Ministry’s intelligence division, and frequently met the Israeli ambassador in the Netherlands.  According to the De Volkskrant report, which cites sources from the Netherlands’ Jewish community, these contacts stalled as Wilders did not turn his agenda into policy. Wilders’ Israeli connections trace back to his youth, when he volunteered for a year at Moshav Tomer, a Jewish settlement in the occupied West Bank, according to the Times of Israel. He also repeatedly referred to Jews as role models for Europe and urged a complete seizure of the West Bank. At one stage, his anti-Muslim slogans made him a star among Dutch Jewish constituencies and beyond. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 15, 2017 19:00:59 GMT

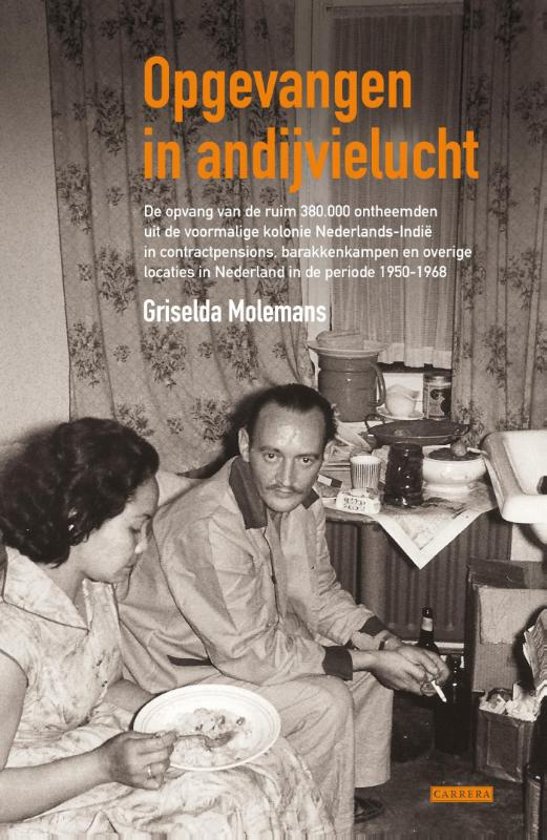

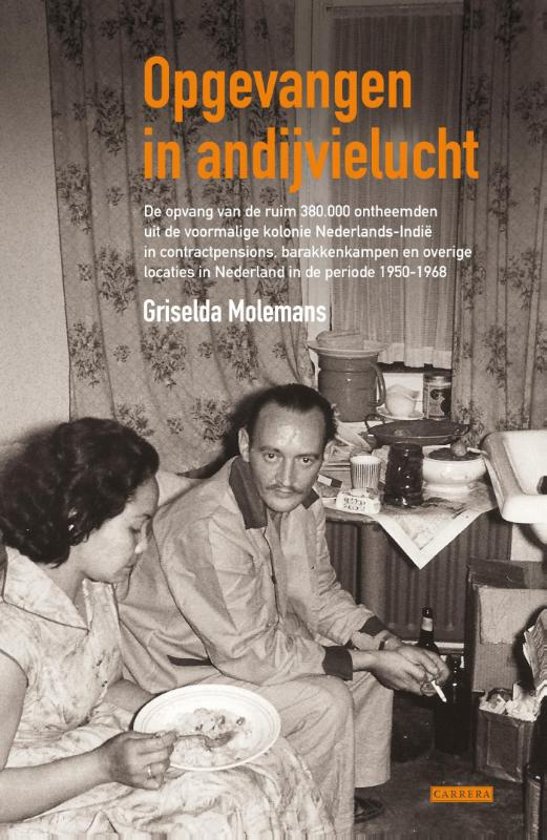

The Netherlands had been fighting a war on two fronts, one in Europe against Germany, and one in Asia, against Japan. As the country was crawling out from underneath its bombed-out cities and realized that more than 70% of Dutch Jews were not returning to the Netherlands, the first war widows and camp survivors from the Dutch East Indies arrived in Holland by the end of 1945, telling similar tales of hardship, camps, starvation and death. The Dutch government paid for the costs of repatriation and temporary housing, convinced that this operation would be terminated by 1948. They were proved wrong. When the transfer of sovereignty happened in 1949, turning the Dutch East Indies into the independent Republic of Indonesia, thousands of mixed-blood Dutch citizens, Indo-European by birth and other ethnicities, refused to become Indonesian citizens and were forced to leave the country of their birth. Arriving in waves, these large groups were perceived as competing with the Dutch for housing, and despised for living off of Dutch tax money to rebuild their lives in The Netherlands (this was not true— they paid for the relief themselves, sometimes taking years to pay off this debt).  The so-called “Indies silence”, which has become a well-known phenomenon among the first generation because of the atrocities they had experienced at the hands of the Japanese during the war and Indonesian revolutionaries right after the war, became even more profound under the pressure of native (Dutch) resentment and prejudice. Years later, the Dutch government misperceived the silence as contentment and used it as propaganda to sell this particular migration of displaced persons (the largest of any population group in Dutch immigration history) as a successful integration and assimilation of the Indo Dutch population. This book tells a very different story and with it, Griselda Molemans breaks through the wall of silence with compelling stories, interviews and facts. The key tenet of the book is Minister Klompé’s (Secretary of Social Affairs) blatant admission at the time that “The Indo Dutch population had been sacrificed for greater interests.” These turned out to be, as Molemans concludes in the end and epilogue of the book, financial interests, confirming an ugly stereotype about the Dutch government that is as old as the famous anti-colonial Dutch novel, Max Havelaar. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 16, 2017 18:55:43 GMT

As the first Indo Dutch prepared for their new lives in the Netherlands right after Indonesia’s independence, they were given warm clothes (often second-hand) on board en route to the Netherlands, for which, as they found out later, they had to pay. Likewise, even though the Dutch were well organized and came into action with several organizations offering relief, the relief was not charitable in nature. As soon as the newcomers found work, 75% and then 60% of their paycheck was withheld to pay the so-called “contractpensions” (housing, providing room and board, contracted by the Dutch State) and other services, like clothes, furniture and social work allowances. The “contractpensions” profited greatly from this model and were generally exploitative: many times, large families had to share one room, and the food quality was often sub par. The former colonials were a lucrative option for the owners of the contractpensions: “They could count on a high occupancy rate and the payments by the government were always made on time.” (p. 46). Clothing manufacturers (like the large department store V&D) profited, too: “The government couldn’t monitor the fact that many refugee families were forced to pay full price for what were essentially sharply discounted clothes.” (p. 156). Also, even though 60% of salaries were withheld to pay the contractpensions and other allowances, when the rates went down for the pensions, the refugees still paid at the 60% rate. In the contractpensions themselves, food, heat and water were often rationed. Most meals consisted of cheap produce like potatoes and endives (hence the title of the book) while meager amounts of meat or fish were served once a week. The refugees weren’t allowed to cook themselves although many did so secretively, on gas burners in their rooms.  What exacerbated the silent suffering was the general opinion of the Dutch population: “The native Dutch population was convinced that the repatriation occurred at the expense of the Dutch taxpayer. The term ‘repatriation’ may seem to have implied this, but ‘repatriation’ was a misnomer, for thousands of Indo Dutch families never returned to their ‘patria’. They were forced to leave the country of their birth (Indonesia), yet they had to pay for their clothing, food and temporary housing. Because of the strict rules and financial burdens, they just kept their mouth shut.” (p. 77). Aside from the financial burdens, the forced move to the Netherlands also tended to be a career demotion. Highly schooled white-collar workers were forced to take on blue collar and inferior jobs because their diplomas from the Dutch East Indies were not recognized and the color of the newcomers’ skin triggered prejudice. The children of the families were discriminated in school (pinda, pinda— peanut, peanut) and Laura Echter-Ruchtie remembers: “Indies people were considered dirty but you ask yourself, who was the dirty one here? When my parents lived in a pension in Scheveningen in 1948, the owner put newspapers in the bathrooms for toilet paper.” (p. 147).  |

|