|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 10, 2016 7:11:18 GMT

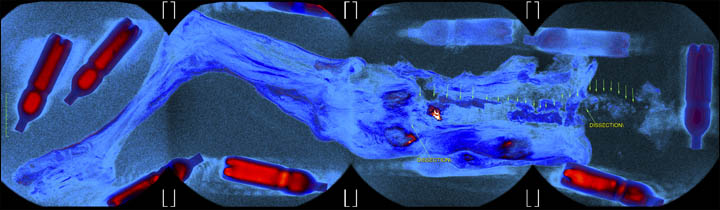

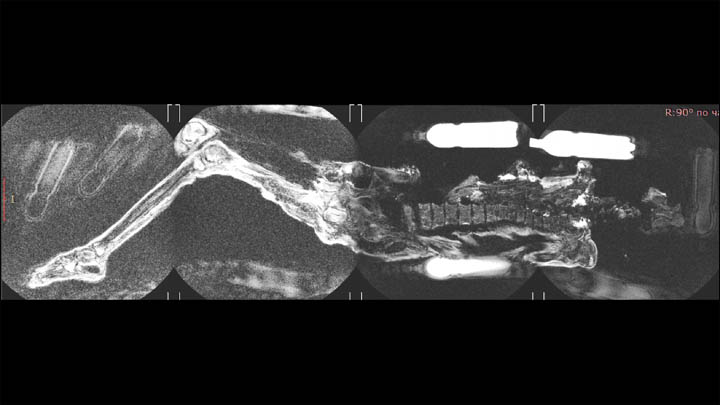

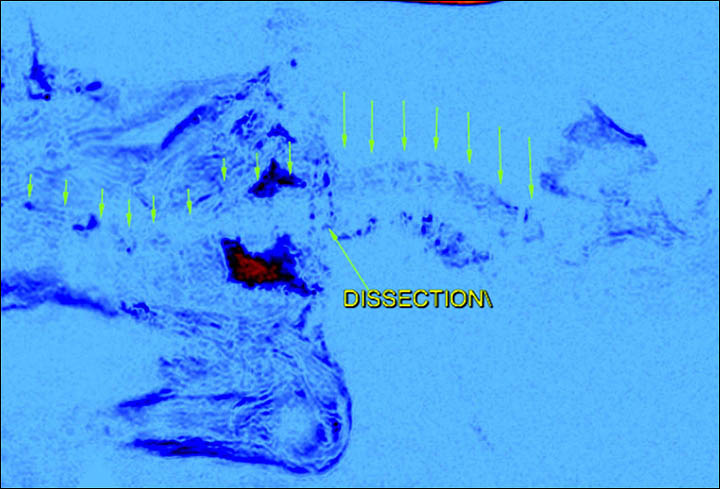

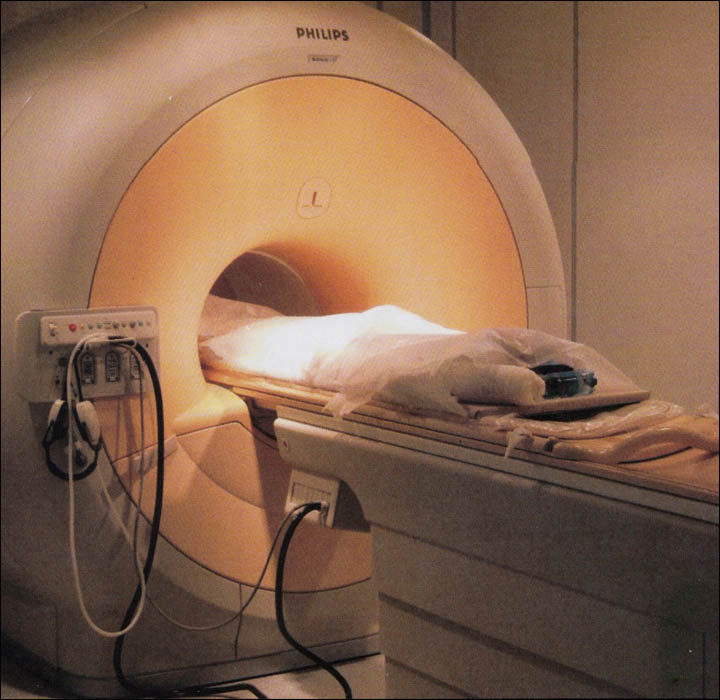

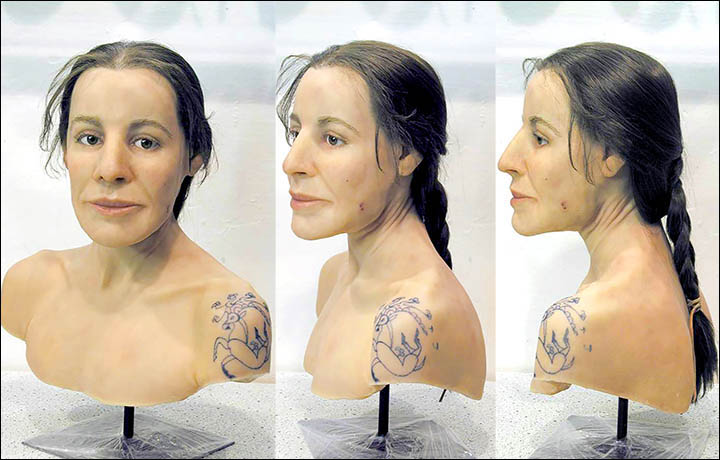

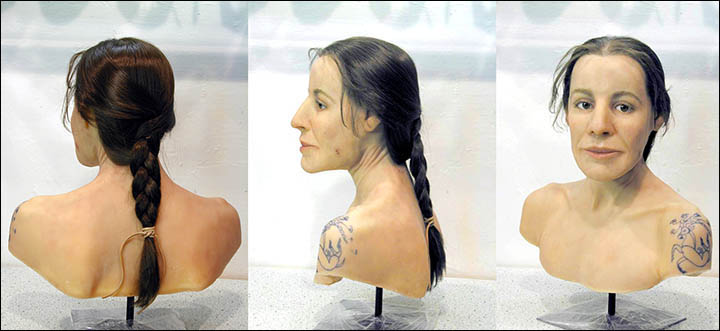

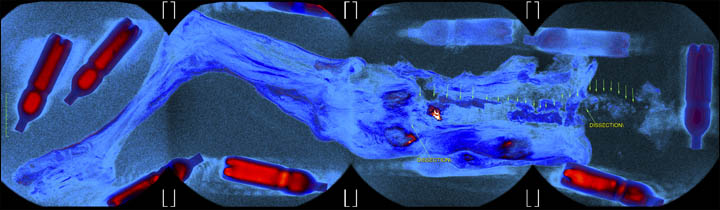

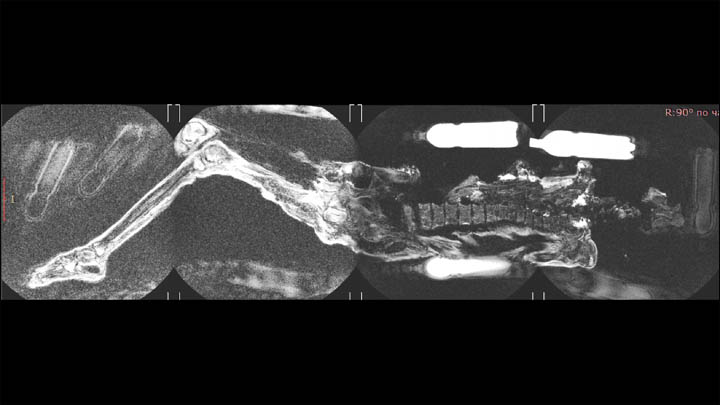

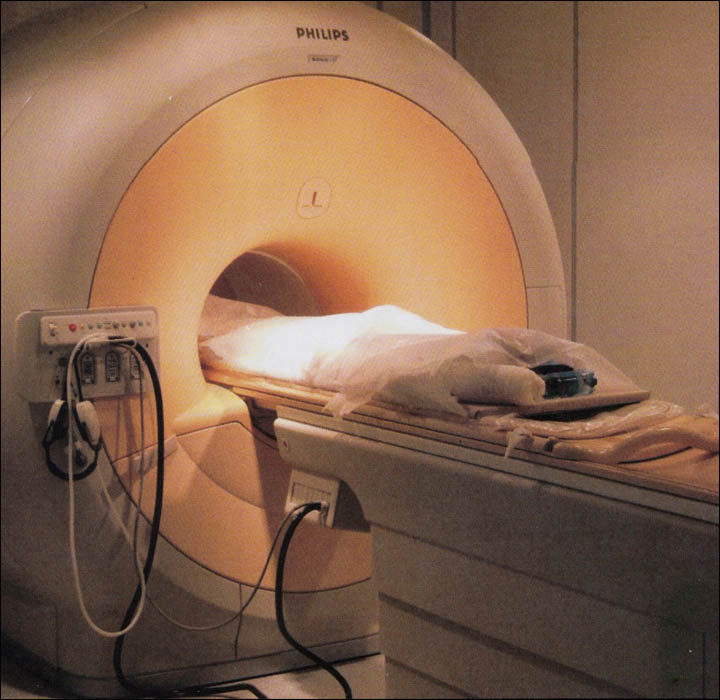

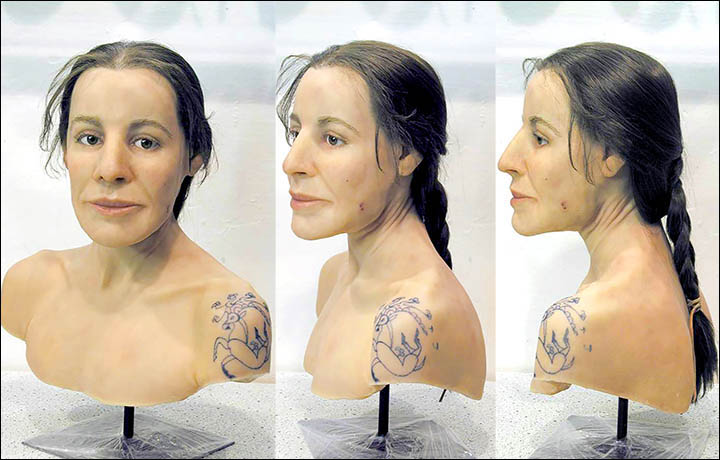

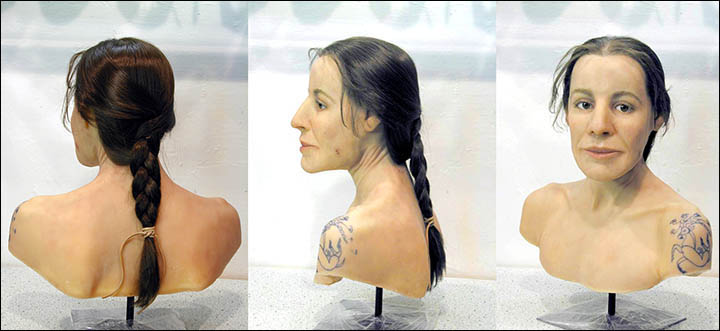

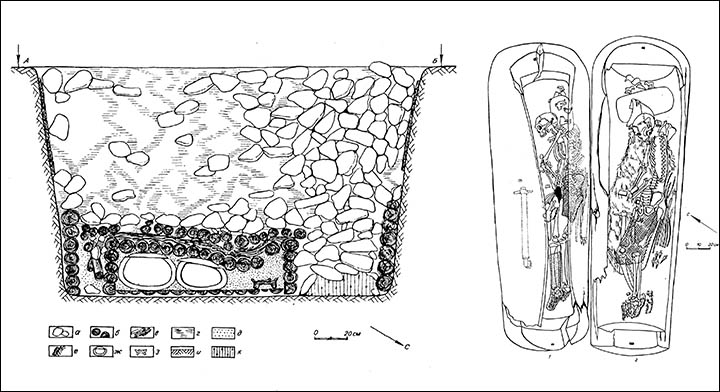

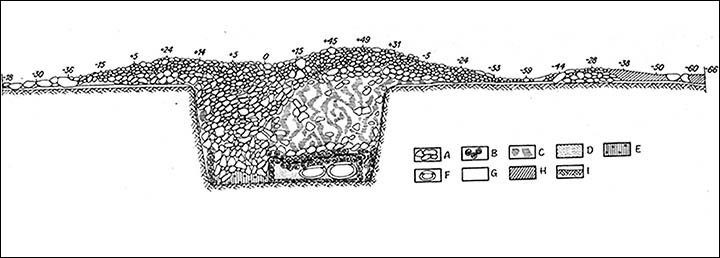

Studies of the mummified Ukok 'princess' - named after the permafrost plateau in the Altai Mountains where her remains were found - have already brought extraordinary advances in our understanding of the rich and ingenious Pazyryk culture. The tattoos on her skin are works of great skill and artistry, while her fashion and beauty secrets - from items found in her burial chamber which even included a 'cosmetics bag' - allow her impressive looks to be recreated more than two millennia after her death.  Now Siberian scientists have discerned more about the likely circumstances of her demise, but also of her life, use of cannabis, and why she was regarded as a woman of singular importance to her mountain people. Her use of drugs to cope with the symptoms of her illnesses evidently gave her 'an altered state of mind', leading her kinsmen to the belief that she could communicate with the spirits, the experts believe.  The MRI, conducted in Novosibirsk by eminent academics Andrey Letyagin and Andrey Savelov, showed that the 'princess' suffered from osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone or bone marrow, from childhood or adolescence. Close to the end of her life, she was afflicted, too, by injuries consistent with a fall from a horse: but the experts also discovered something far more significant.  'When she was a little over 20 years old, she became ill with another serious disease - breast cancer. It painfully destroyed her' over perhaps five years, said a summary of the medical findings in 'Science First Hand' journal by archeologist Professor Natalia Polosmak, who first found these remarkable human remains in 1993. 'During the imaging of mammary glands, we paid attention to their asymmetric structure and the varying asymmetry of the MR signal,' stated Dr Letyagin in his analysis. 'We are dealing with a primary tumour in the right breast and right axial lymph nodes with metastases.'  'The three first thoracic vertebrae showed a statistically significant decrease in MR signal and distortion of the contours, which may indicate the metastatic cancer process.' He concluded: 'I am quite sure of the diagnosis - she had cancer. She was extremely emaciated. Given her rather high rank in society and the information scientists obtained studying mummies of elite Pazyryks, I do not have any other explanation of her state. Only cancer could have such an impact.  'When she arrived in winter camp on Ukok in October, she had the fourth stage of breast cancer,' she wrote. 'She had severe pain and the strongest intoxication, which caused the loss of physical strength. 'In such a condition, she could fall from her horse and suffer serious injuries. She obviously fell on her right side, hit the right temple, right shoulder and right hip. Her right hand was not hurt, because it was pressed to the body, probably by this time the hand was already inactive. Though she was alive after her fall, because edemas are seen, which developed due to injuries.  'Anthropologists believe that only her migration to the winter camp could make this seriously sick and feeble woman mount a horse. More interesting is that her kinsmen did not leave her to die, nor kill her, but took her to the winter camp.'In other words, this confirmed her importance, yet though she is often called a 'princess', the truth maybe she was was - in fact - a female shaman.  'It looks like that after arriving to the Ukok Plataue she never left her bed,' she said. 'The pathologist believes that her body was stored before the funerals for not more than six months, more likely it was two-to-three months. 'She was buried in the middle of June - according the last feed that was found in the stomachs of horses buried alongside her. The scientists think that she died in January or even March, so she was alive after her fell for about three to five months, and all this time she lay in bed.' |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 11, 2016 7:07:50 GMT

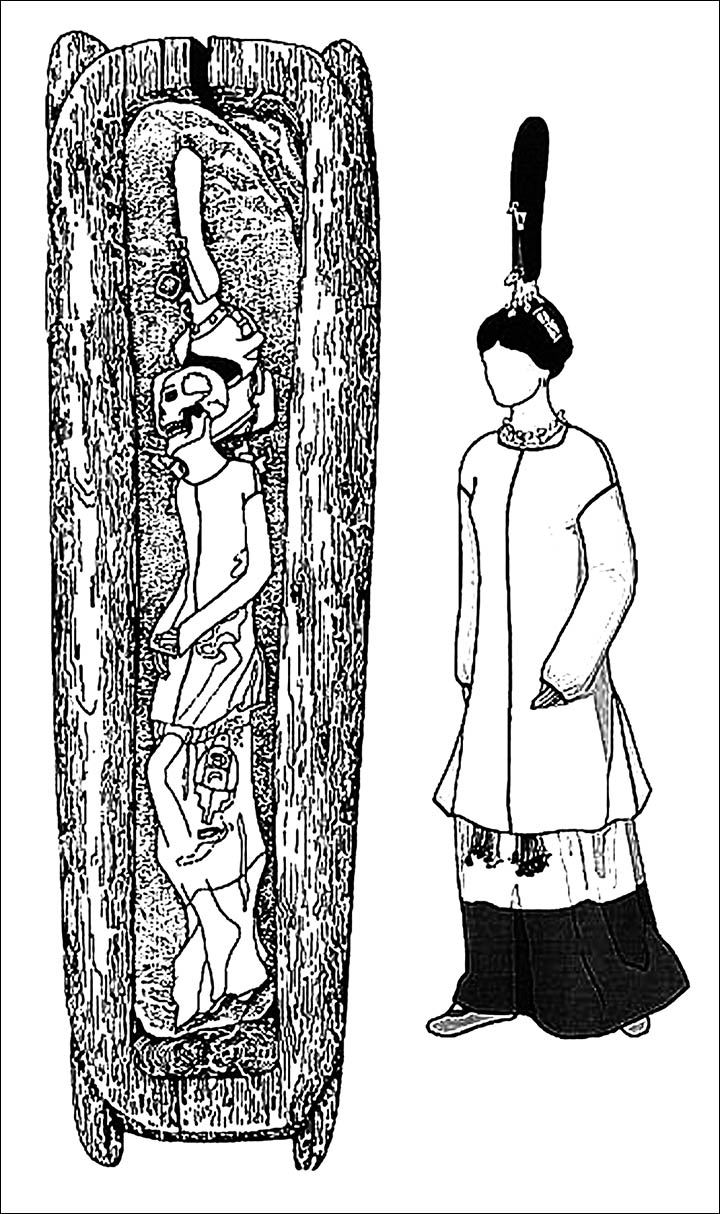

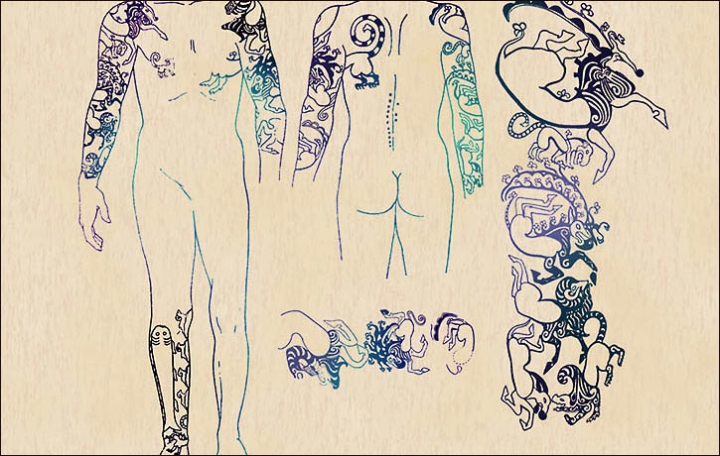

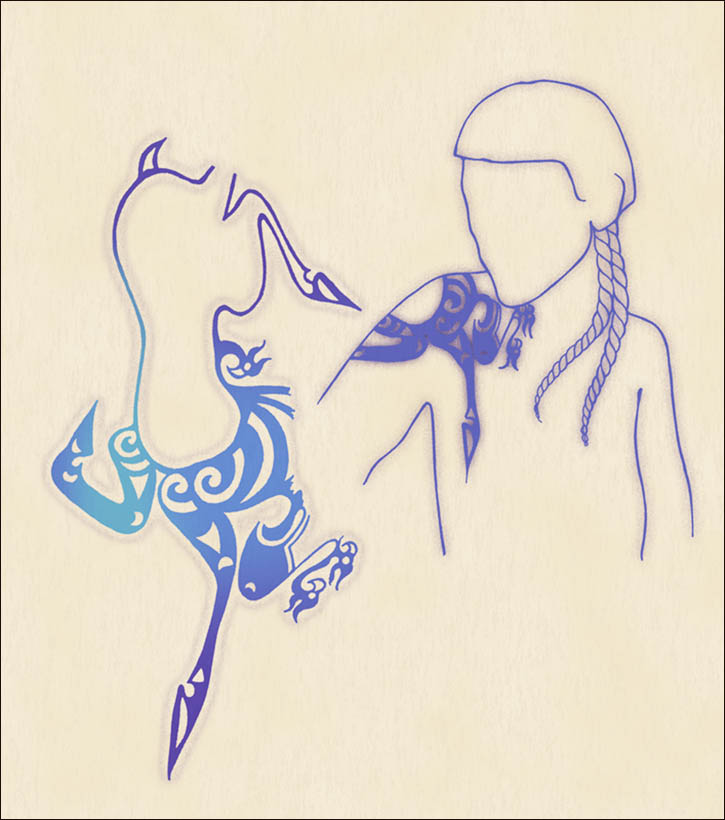

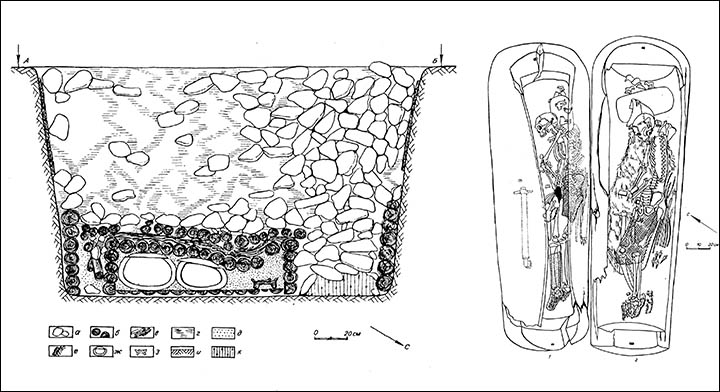

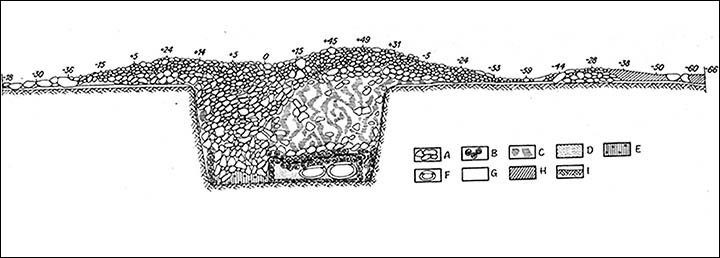

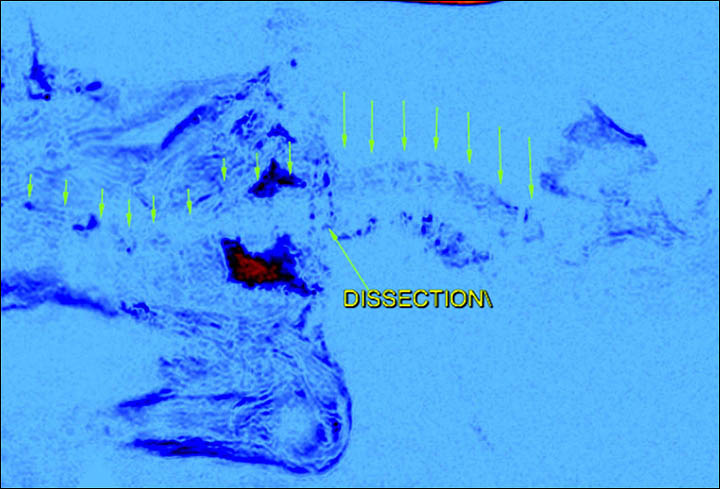

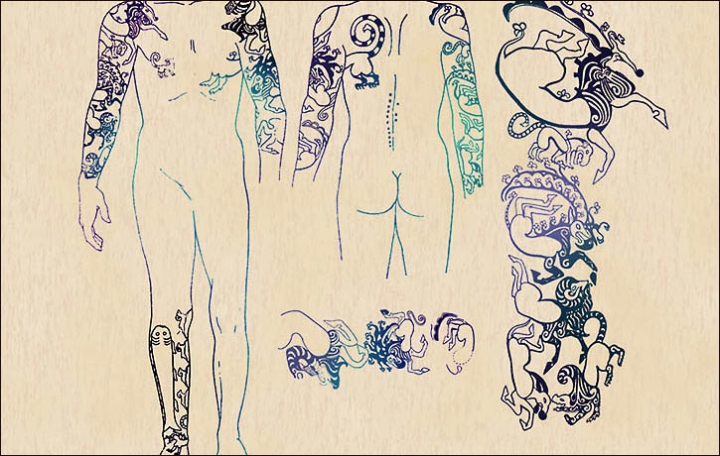

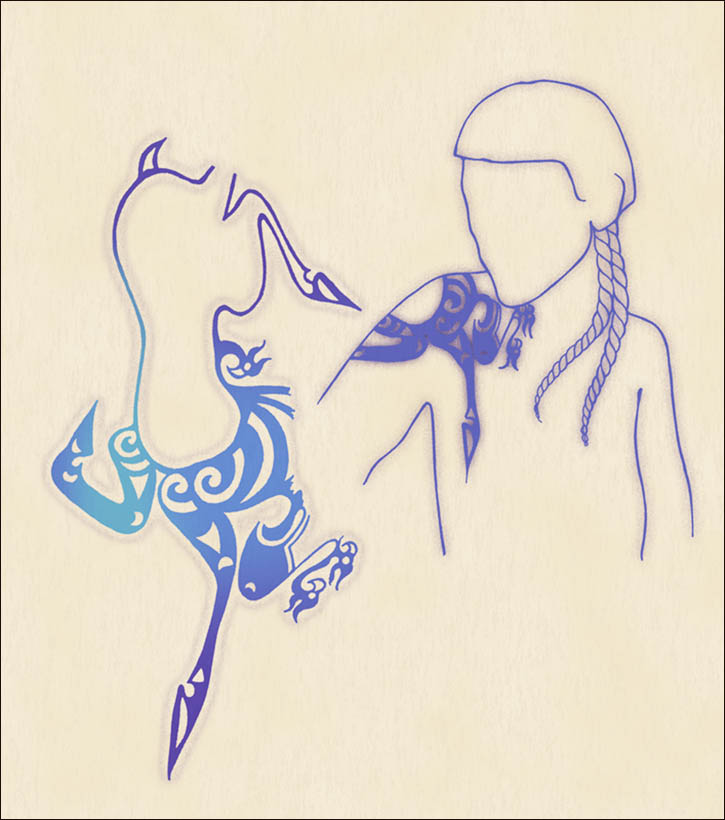

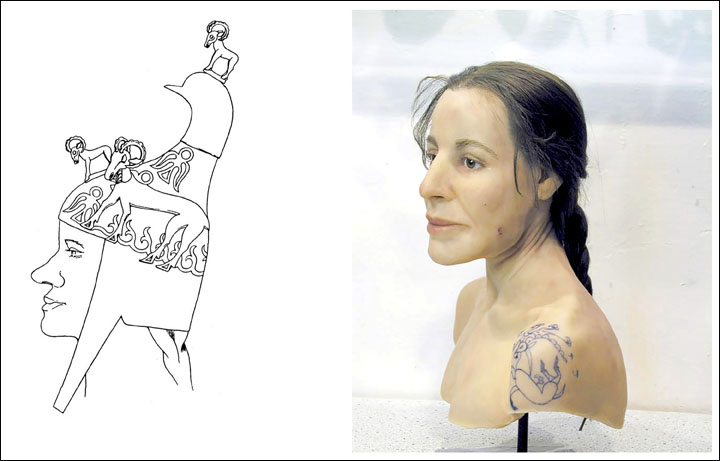

She is to be kept in a special mausoleum at the Republican National Museum in capital Gorno-Altaisk, where eventually she will be displayed in a glass sarcophagus to tourists. For the past 19 years, since her discovery, she was kept mainly at a scientific institute in Novosibirsk, apart from a period in Moscow when her remains were treated by the same scientists who preserve the body of Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin.  To mark the move 'home', The Siberian Times has obtained intricate drawings of her remarkable tattoos, and those of two men, possibly warriors, buried near her on the remote Ukok Plateau, now a UNESCO world cultural and natural heritage site, some 2,500 metres up in the Altai Mountains in a border region close to frontiers of Russia with Mongolia, China and Kazakhstan. They are all believed to be Pazyryk people - a nomadic people described in the 5th century BC by the Greek historian Herodotus - and the colourful body artwork is seen as the best preserved and most elaborate ancient tattoos anywhere in the world.  The remains of the immaculately dressed 'princess', aged around 25 and preserved for several millennia in the Siberian permafrost, a natural freezer, were discovered in 1993 by Novosibirsk scientist Natalia Polosmak during an archeological expedition.  Buried around her were six horses, saddled and bridled, her spiritual escorts to the next world, and a symbol of her evident status, perhaps more likely a revered folk tale narrator, a healer or a holy woman than an ice princess. There, too, was a meal of sheep and horse meat and ornaments made from felt, wood, bronze and gold. And a small container of cannabis, say some accounts, along with a stone plate on which were the burned seeds of coriander.  'Compared to all tattoos found by archeologists around the world, those on the mummies of the Pazyryk people are the most complicated, and the most beautiful,' said Dr Polosmak. More ancient tattoos have been found, like the Ice Man found in the Alps - but he only had lines, not the perfect and highly artistic images one can see on the bodies of the Pazyryks.  The tattoos on the left shoulder of the 'princess' show a fantastical mythological animal: a deer with a griffon's beak and a Capricorn's antlers. The antlers are decorated with the heads of griffons. And the same griffon's head is shown on the back of the animal.  The mouth of a spotted panther with a long tail is seen at the legs of a sheep. She also has a deer's head on her wrist, with big antlers. There is a drawing on the animal's body on a thumb on her left hand. On the man found close to the 'princess', the tattoos include the same fantastical creature, this time covering the right side of his body, across his right shoulder and stretching from his chest to his back. The patterns mirror the tattoos on a much more elaborately covered male body, dug from the ice in 1929, whose highly decorated torso is also reconstructed in our drawing here. The Princess of Ukok is not related, evidently, to the present day inhabitants of Altai. Moreover, she had a European appearance, it has been claimed. 'There was a moment of gross misunderstanding when a legend came about this mummy being a foremother of people of Altai,' said Molodin. 'The people of Pazyryk belonged to different ethnic group, in no way related to Altaians. Genetic studies showed that the Pazyryks were a part of Samoyedic family, with elements of Iranian-Caucasian substratum.' So perhaps more Samoyedic than Scythian. |

|

|

|

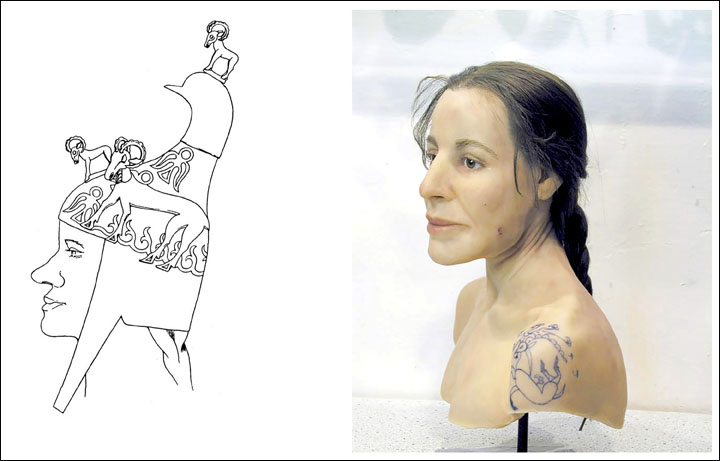

Post by Admin on Jan 13, 2016 6:52:10 GMT

A Swiss taxidermy expert brought 'her' to life, recreating the 'virgin' warrior's looks from facial bones, and some observers commented on her distinctly masculine appearance. Yet archeologists and anthropologists believed she was not only female - and a pig-tailed teenager - but a member of an elite corps of warriors within the Pazyryk culture which suggested likenesses to the fabled Amazon warriors of known to the Greeks.  Entombed next to a much older man - perhaps father and daughter? - the remains lay beside shields, battle axes, bows and arrowheads, while the warrior's physique indicated a skilled horse rider and archer. Cowrie shells, amulets for female fertility but exceptionally rare in Pazyryk burials, were a tell-tale sign that this was a young woman, but so were various adornments to the grave - for example, the 'coffin', the wooden pillow, the quiver, all smaller in comparison to usual male burials. In a singular honour, nine horses - four of them bridled - were buried with the skeleton, an escort to the afterlife.  This obtained 'reliable molecular genetic data' indicating that the supposed female warrior 'was male', according to a report released by Science First Hand co-authored by Dr Alexander Pilipenko, of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, and Dr Natalia Polosmak, of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, at the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, in Novosibirsk.  The research also found that the relationship between the two people buried in the tomb at the Ak-Alakha 1 Mound 1 was not father and son but perhaps uncle and nephew. The cause of death of the pig-tailed ancient youth was not established.  |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 17, 2016 8:42:21 GMT

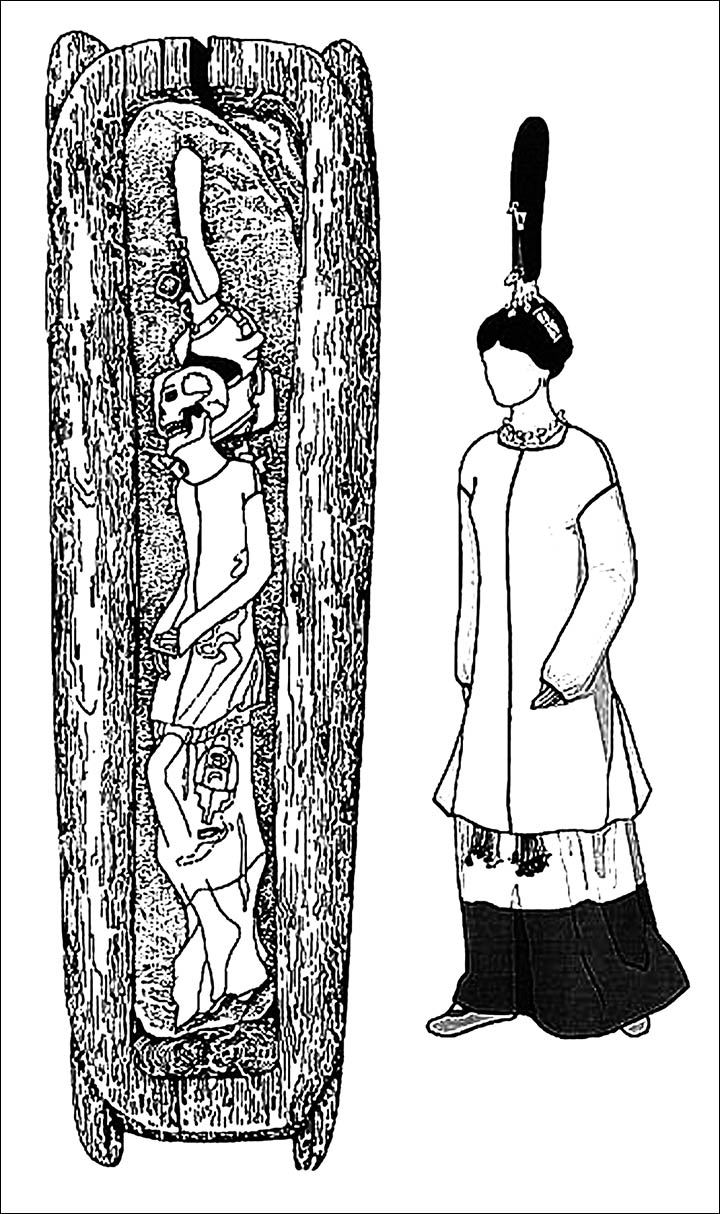

The slashed and punctured bones of a woolly mammoth suggest that humans lived in the far northern reaches of Siberia earlier than scientists had previously thought, a new study finds. Before the surprising discovery, researchers thought that humans lived in the freezing Siberian Arctic no earlier than about 30,000 to 35,000 years ago. Now, the newly studied mammoth carcass suggests that people lived in the area, where they butchered the likes of this giant animal about 45,000 years ago.  Paleolithic human remains are rarely found in the Eurasian Arctic. But all expectations were overturned in 2012, when a team found the carcass of an "exceptionally complete" woolly mammoth on the eastern shore of Yenisei Bay, located in the central Siberian Arctic, the researchers wrote in the study. The extreme cold preserved some of the male mammoth's soft tissue, including the remains of its fat hump and its penis, they said.  However, injuries found on the mammoth's bones — including its ribs, left shoulder bone, right tusk and cheekbone — suggest that it had a violent end. Some of the bones have dents and punctures, possibly from thrusting spears, the researchers said. The ancient hunters likely removed the mammoth's tongue and some of its internal organs, but it's unclear why they didn't take more of the beast.  Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers dated the mammoth's tibia (shinbone) and surrounding materials to about 45,000 years ago. Radiocarbon dating measures the amount of carbon-14 (a carbon isotope, or variant with a different number of neutrons in its nucleus) left in a once-living organism, and can be used reliably to date material to about 50,000 years ago, although some techniques allow researchers to date older organic objects.  The researchers also found a Pleistocene wolf humerus (arm bone) that had been injured by a "sharp implement with a conical tip," Pitulko said in the statement. The bone, also discovered in Arctic Siberia, dates to about 47,000 years ago, they found. The wolf bone was uncovered near the bones of ancient bison, reindeer and rhinoceros, all of which have evidence of human modification. This finding suggests that ancient humans hunted and ate a variety of mammals, not just mammoths, Pitulko said.  Paleolithic records of humans in the Eurasian Arctic (above 66°N) are scarce, stretching back to 30,000 to 35,000 years ago at most. Pitulko et al. have found evidence of human occupation 45,000 years ago at 72°N, well within the Siberian Arctic. The evidence is in the form of a frozen mammoth carcass bearing many signs of weapon-inflicted injuries, both pre- and postmortem. The remains of a hunted wolf from a widely separate location of similar age indicate that humans may have spread widely across northern Siberia at least 10 millennia earlier than previously thought. Archaeological evidence for human dispersal through northern Eurasia before 40,000 years ago is rare. In west Siberia, the northernmost find of that age is located at 57°N. Elsewhere, the earliest presence of humans in the Arctic is commonly thought to be circa 35,000 to 30,000 years before the present. A mammoth kill site in the central Siberian Arctic, dated to 45,000 years before the present, expands the populated area to almost 72°N. The advancement of mammoth hunting probably allowed people to survive and spread widely across northernmost Arctic Siberia. Science 15 Jan 2016: Vol. 351, Issue 6270, pp. 260-263 |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Apr 6, 2016 1:11:17 GMT

A council of elders in Russia’s Altay Region voted to bury the mummy of a woman who lived in the region in the 5th century BC. Altay locals believe that her excavation from her tomb back in 1993 angered her spirit and causes natural disasters. The mummy, dubbed the Siberian Ice Maiden in English-language sources and the Princess of Ukok, the Altay Princess or Ochi-Bala domestically, was unearthed from a subterranean tomb at the Ukok Plateau, close to borders with Kazakhstan, China and Mongolia. The remains have spent most of the time thereafter at a research facility in Novosibirsk, as scientists conducted facial reconstruction, DNA tests and other research projects on the Maiden. But in 2012, the unique specimen was returned to the Altay Region to be placed at a special mausoleum at a local national museum. Many people in Altay believe that the remains to belong to a legendary ancestor and a powerful princess. Some even say that her tomb was placed to keep a gate to the underworld closed and that the absence of the guardian has led to natural disasters in Altay, including the 2003 earthquake and this year’s record floods.  Ironically, DNA tests on the Ice Maiden, and other remains of people who belonged to the nomadic Pazyryk culture that inhabited the Ukok Plateau, proved that she cannot be an ancestor of the people living in the Altay Region now. The Pazyryk are genetically closest to Siberian Ket and Selkup peoples, but are further from the Altay people than from, for example, Germans, Basques or Russians.  |

|