|

|

Post by Admin on Nov 22, 2018 18:17:53 GMT

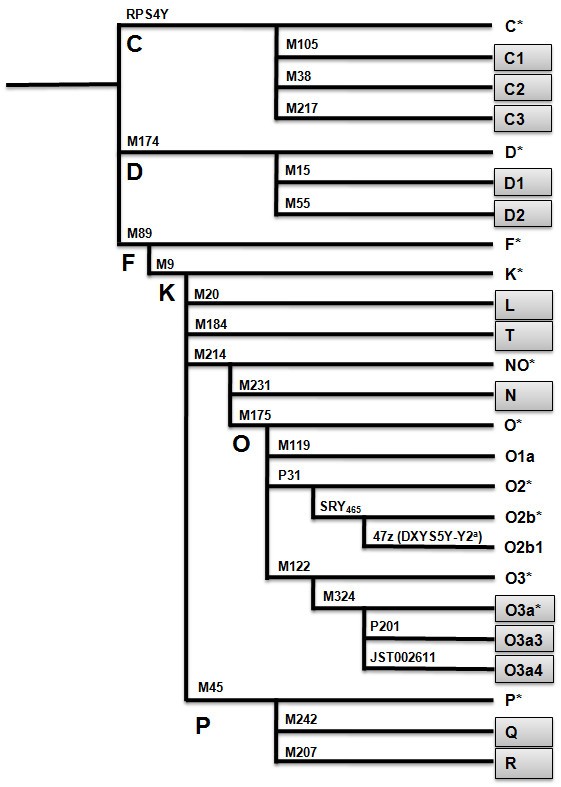

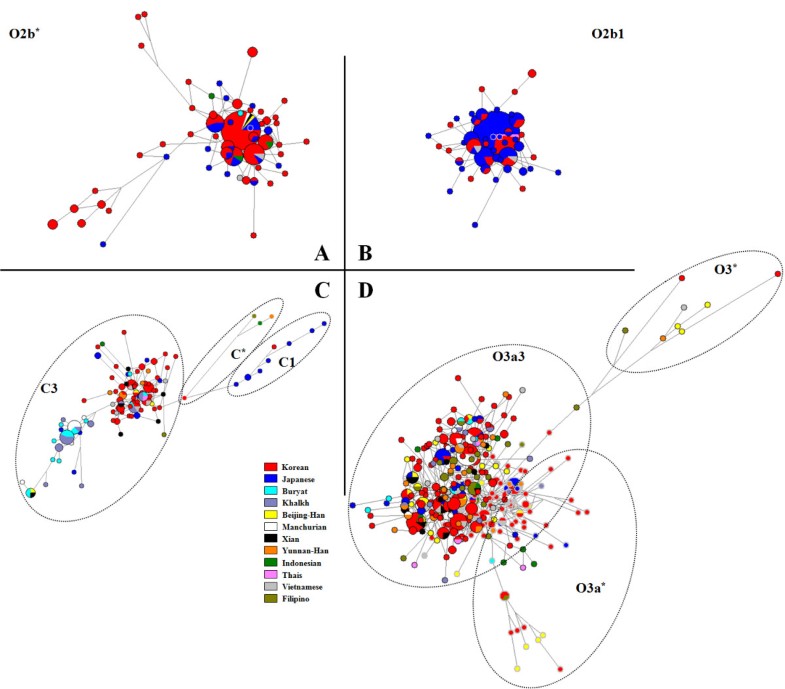

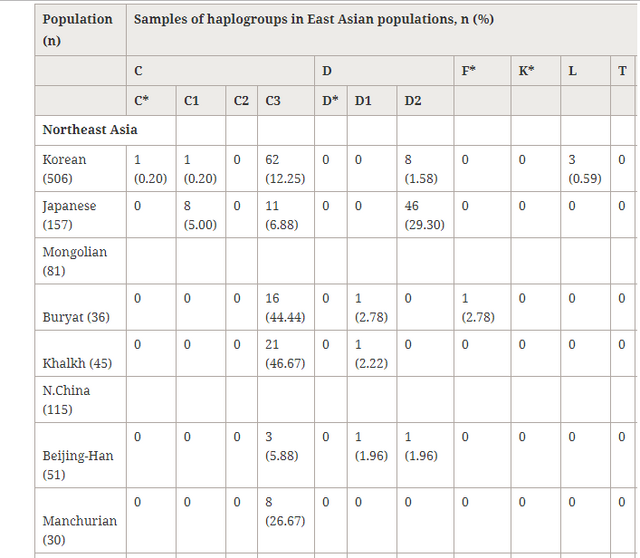

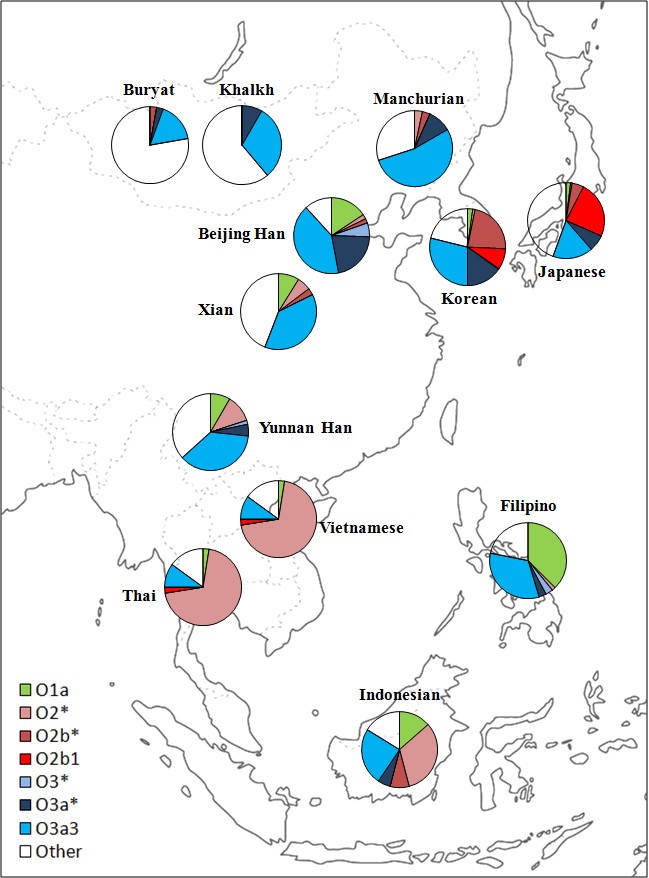

Figure 1 Background Koreans are generally considered a Northeast Asian group, thought to be related to Altaic-language-speaking populations. However, recent findings have indicated that the peopling of Korea might have been more complex, involving dual origins from both southern and northern parts of East Asia. To understand the male lineage history of Korea, more data from informative genetic markers from Korea and its surrounding regions are necessary. In this study, 25 Y-chromosome single nucleotide polymorphism markers and 17 Y-chromosome short tandem repeat (Y-STR) loci were genotyped in 1,108 males from several populations in East Asia. Results In general, we found East Asian populations to be characterized by male haplogroup homogeneity, showing major Y-chromosomal expansions of haplogroup O-M175 lineages. Interestingly, a high frequency (31.4%) of haplogroup O2b-SRY465 (and its sublineage) is characteristic of male Koreans, whereas the haplogroup distribution elsewhere in East Asian populations is patchy. The ages of the haplogroup O2b-SRY465 lineages (~9,900 years) and the pattern of variation within the lineages suggested an ancient origin in a nearby part of northeastern Asia, followed by an expansion in the vicinity of the Korean Peninsula. In addition, the coalescence time (~4,400 years) for the age of haplogroup O2b1-47z, and its Y-STR diversity, suggest that this lineage probably originated in Korea. Further studies with sufficiently large sample sizes to cover the vast East Asian region and using genomewide genotyping should provide further insights. Conclusions These findings are consistent with linguistic, archaeological and historical evidence, which suggest that the direct ancestors of Koreans were proto-Koreans who inhabited the northeastern region of China and the Korean Peninsula during the Neolithic (8,000-1,000 BC) and Bronze (1,500-400 BC) Ages. Technitially all the samples were analyzed for 12 Y-SNP markers (M9, M45, M89, M119, M122, M174, M175, M214, P31, SRY465, 47z and RPS4Y) using a previously described protocol [17]. The samples belonging to haplogroups C, D, K, NO, O3 and P were subjected to further typing with an additional 13 Y-SNP markers to designate the subclades: two three-plex, three two-plex and one single-plex SNaPshot assay were developed for these 13 Y-SNP markers (Figure 1). The nomenclature of the haplogroups followed that of the Y Chromosome Consortium [20]. Primers for PCR and single-base extension (SBE) reactions were designed (Primer 3.0 program; frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/, Cambridge, MA, USA) (see Additional file 1, Table S1; see Additional file 2, Table S2). Conditions of the SNaPshot assays were the same as those previously described [17], with the exception of PCR purification; in our assay, the PCR products were purified by adding 2 μl of an exonuclease I-shrimp alkaline phosphatase preparation (Exo-SAP; USB Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA) to 5 μl PCR product.  Table 2 Distribution of Y chromosome haplogroup frequencies in the East Asian populations studied |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Nov 24, 2018 18:09:00 GMT

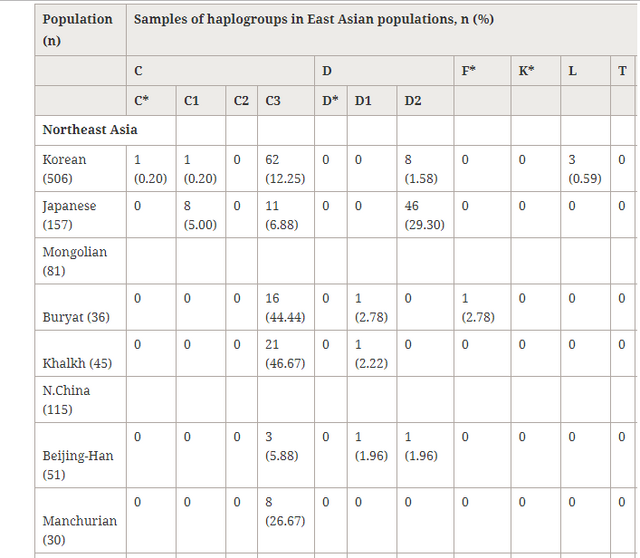

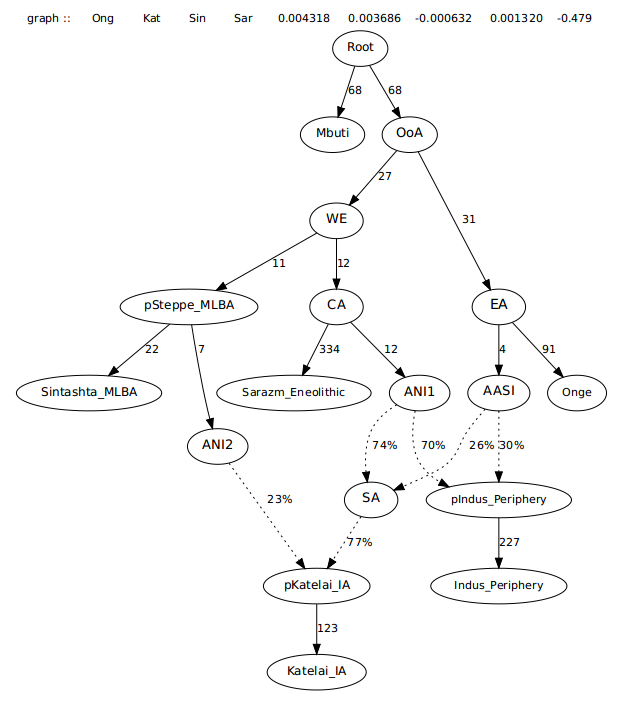

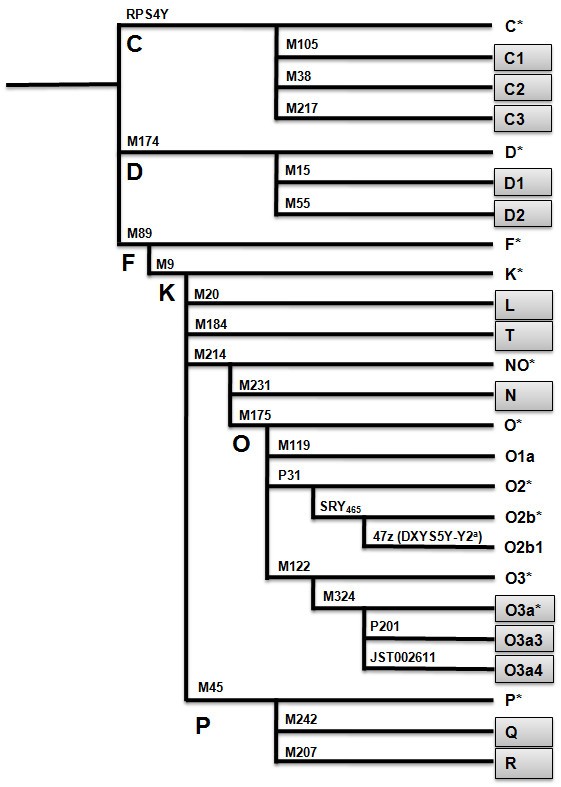

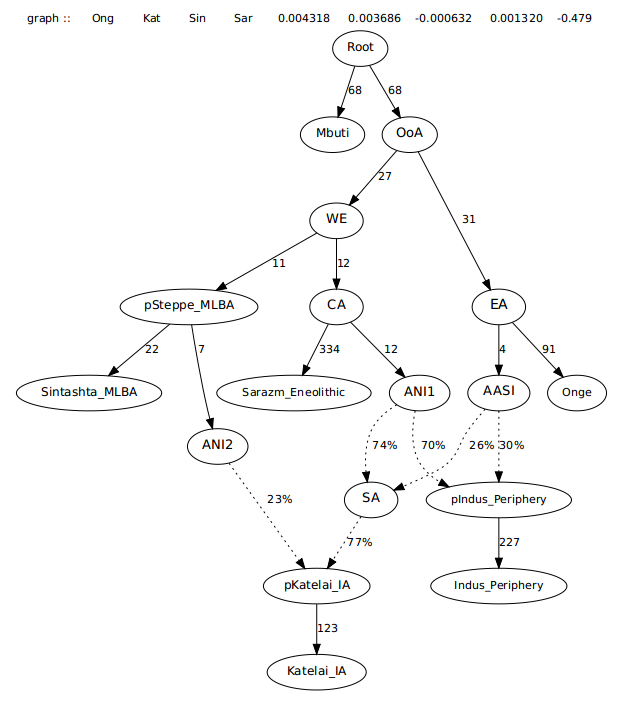

Figure 2 Distribution of Y haplogroup O lineages in East Asia. Circled areas are proportional to haplogroup frequency, and haplogroups are represented by different colors. Based on recent studies of Y-chromosome variation, the East Asian gene pool is almost completely contained within three major Y-chromosome lineages (haplogroups C, D and K) [7, 10]. East Asian populations have major expansions of haplogroup O-M175 lineages (a lineage within K), although there are significant genetic differences in other lineages between the populations [8, 11]. Most Y chromosomes found in the Korean population also belong to haplogroup O-M175 and its sublineages [8, 9]. The Korean population has a high frequency of the haplogroup O3-M122 lineage, which is shared mainly with Chinese and Southeast Asian populations. By contrast, the haplogroup O2b-SRY465 lineages (and its sublineage) are found with high frequency and diversity specifically among modern populations of Japan and Korea [8, 12, 13]. These chromosomes are absent in most populations in China, but they have been detected in some samples of Beijing-Han Chinese, Manchurians, Mongolians and Southeast Siberians [7, 8, 14]. Hammer and Horai [12] hypothesized that the haplogroup O2b-SRY465 and its sublineage, O2b1-47z, might be Yayoi male lineages, which contributed to the contemporary mainland Japanese population via a process of demic diffusion during the Yayoi period from the Korean Peninsula, around 2,300 years ago. Hammer et al.[13] also suggested that the haplogroup O2b1-47z mutation arose on an ancestral O2b-SRY465 chromosome during early phases of the Yayoi migration. This lineage is also distributed sporadically in the Mongol, Manchu and Southeast Siberian populations, and in Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Micronesia [8, 13, 14]. Lin et al.[15] suggested that the O2b1-47z Y chromosome associated with the Y2 allele might have originated from an ancestral population in Henan or the southern parts of Shanxi near the Yellow River in China.  O3-M122 was the commonest Chinese Y-chromosome haplogroup found, and its presence in Korea may originate from demic diffusion by way of south-to-north migration [9, 29, 30]. C-RPS4Y was the commonest Mongolian Y-chromosome haplogroup (C3 lineage), and this is shared primarily with populations in northern Asia (including Koreans) [9, 31, 32]. Our network and diversity analyses of C-RPS4Y and O3 may support a southern origin that migrated into East Asia via the southern route [10, 29] (Figure 3, Table 3). Interestingly, our Japanese group seemed to have both C1-M105 and C3-M217 chromosomes, whereas haplogroup C1-M105 was not present in most East Asian populations (except for Koreans), consistent with the previous report of Hammer et al. [13]. Haplogroup D2-M55 was found at high frequency only in Japanese subjects (29.3%), including 1.6% of Koreans, whereas it was absent elsewhere in these East Asian populations, except for the Beijing-Han group. Haplogroup D1-M15 was present at extremely low frequencies in the other East Asian populations. The occurrence of C1 and D2 chromosomes in Korea may be considered concordant with the historical views about the recent connection between the Korean and Japanese populations.  Haplogroup D-M174's migration pattern fits in well with the scenario proposed by Chaubey et al. (2011), which is found at high frequency among populations in Tibet and the Andaman Islands, and at moderate frequencies among indigenous Chinese tribes. Haplogroup D-M55, which is closely associated with the Jomon and Ainu, was born in Japan 38,000-37,000 years before present, around 10,000 years after the split between AASI and AncientPapuan. In our fitted admixture graph, AASI, Onge, and AncientPapuan (a hypothesized ancestral population to modern Papuans, prior to Denisovan admixture) are a clade with respect to Nicobarese, representing the East Eurasian ancestry that plausibly dispersed with the Austroasiatic language expansion, and indigenous Chinese groups. The split between AASI, Onge, AncientPapuan is modeled as nearly a trifurcation. It seems probable that the split between AASI and AncientPapuan occurred prior to modern humans reaching Sahul (the ancient continent uniting Australia and New Guinea). Radiocarbon dating shows this is unlikely to be much more recently than 47,000 years before present (Chaubey et al. 2011). |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Nov 26, 2018 18:07:15 GMT

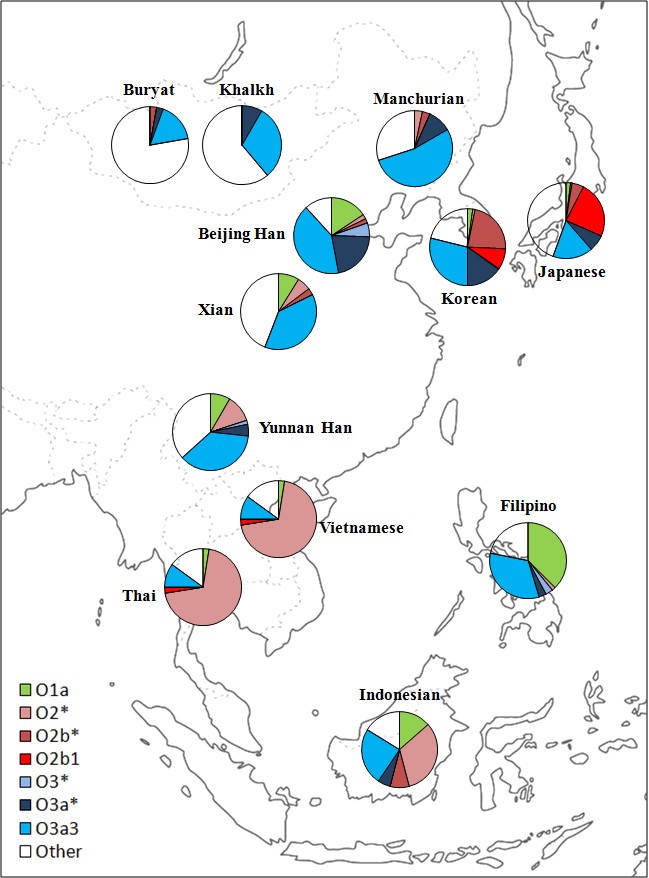

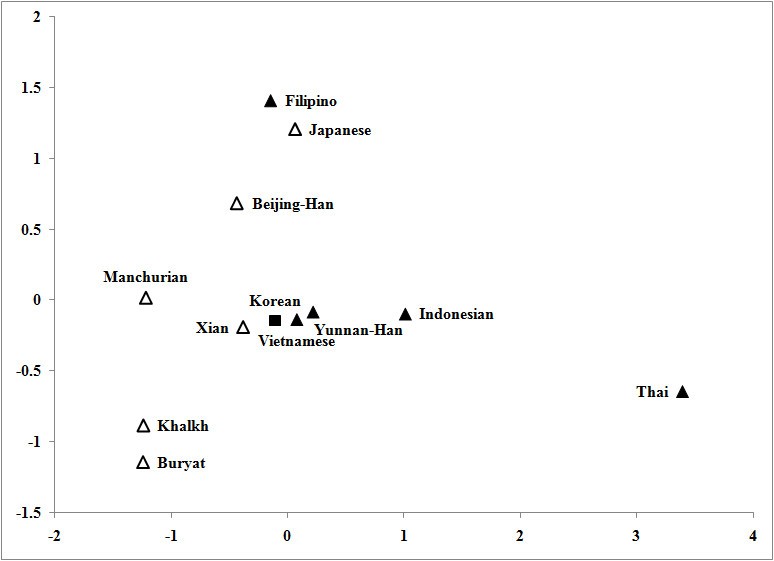

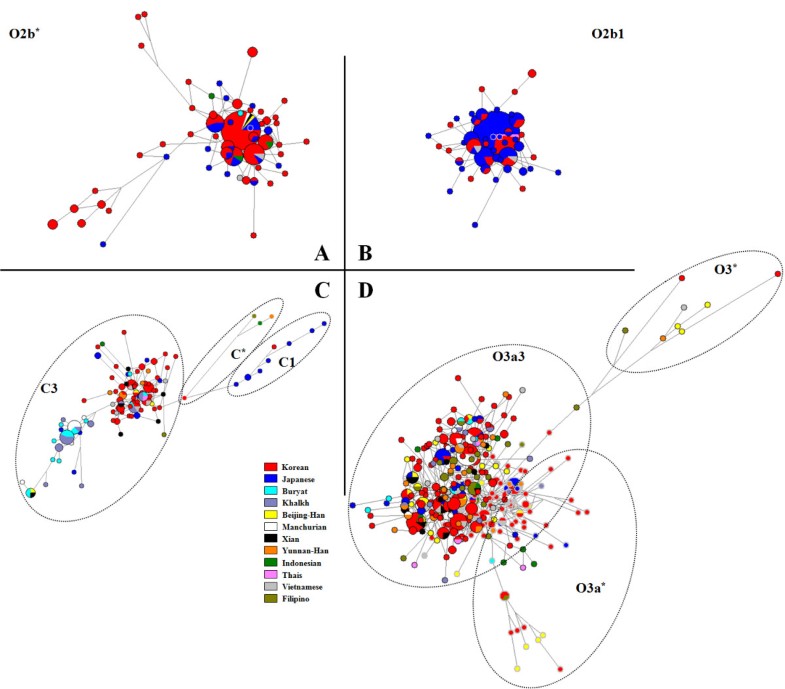

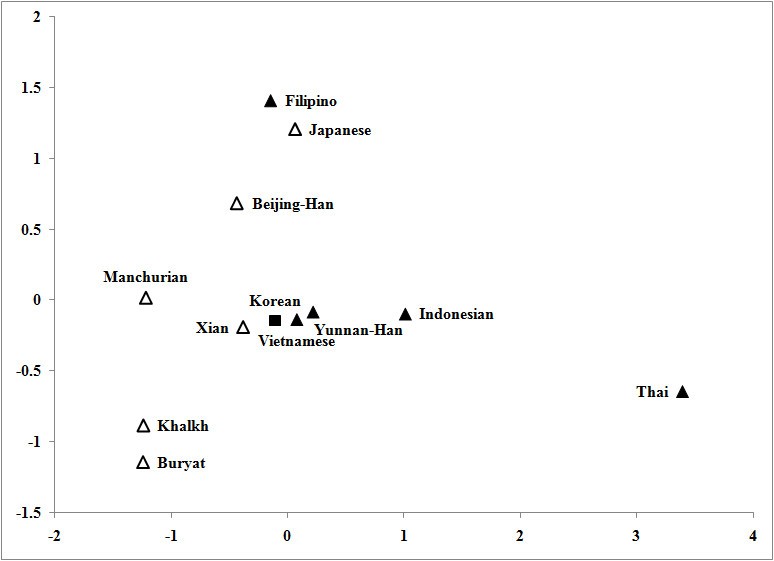

Figure 3 Median-joining network for East Asian Y haplogroup lineages based on the minimum nine Y-chromosome short tandem repeat (Y-STR) haplotypes. (A) Network of haplogroup O2b*; (B) network of haplogroup O2b1; ( C) network of haplogroup C; (D) network of haplogroup O3. Circled areas are proportional to haplotype frequency; lines represent the mutational differences between haplotypes. Haplogroup N-M231 was present in the Korean and Mongolian groups at moderate frequencies, suggesting that the early Korean population may have shared a common origin with Mongolian ethnic groups who inhabited the general area of the Altai Mountains and Lake Baikal regions of southeastern Siberia [1]. The K-M9 defined chromosomes (L, Q and R subtypes) were also found at low frequencies in the Korean group, and these mainly occur in central and south Asia [13, 33]. The presence of these haplogroups in the Korean population implies that the peopling of Korea probably involved multiple events [8, 9]. Based on the result of the MDS plot (Figure 4 and Additional file 4, Table S4), the Korean population contains lineages from both the southern and northern areas of East Asia.  Figure 4 Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot based on F ST distances of 12 populations in East Asia (see Additional file 4, Table S4). Square = Koreans, open triangles = Northeast Asians, closed triangles = Southeast Asians. Age estimates based on our Y-STR data provide further support for the initial expansion of the O2b*-SRY465 in prehistoric Korea, in accordance with the proto-Korean lineages. Based on the Korean demographic and population history, a constant population in three different BATWING models may give the best fit to our data. Thus, time to most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) for the O2b*-SRY465 lineages was 9,900 years, assuming constant population size (Table 6). According to the three different population expansion models, TMRCA within the Korean and Japanese populations and the whole of East Asia ranged from 6,000-10,000 years ago. This date corresponds to the early Neolithic Age in Korea. Therefore, the age of the O2b*-SRY465 and pattern of variation within the lineages suggests a Neolithic proto-Korean founder in a nearby part of northeastern Asia, followed by a population increase in the vicinity of the Korean Peninsula.  Interestingly, the O2b1-47z sublineage seems to have diverged about 4,400 years ago (Table 6) rather than in the Yayoi period, consistent with a previous estimate of 4,000 years ago [13]. Therefore, the present data support the possibility of an ancient Korean origin of O2b1-47z, rather than a Japanese origin [13]. Although O2b1-47z is at its highest haplogroup frequency in the Japanese population, the Y-STR data reveal more diversity of O2b1-47z haplotypes in Koreans, as shown by the mean number of pairwise differences and allele size variation ratio (Table 5), supporting an origin of the O2b1-47z mutation in prehistoric Korea. The Japanese samples studied here were derived from Kyushu, Shikoku and southern Honshu (the region closest to Korea), implying that the high frequency of the O2b1 lineage in Japan may be explained by genetic drift [12, 16]. This finding is concordant with a previous report of Nonaka et al.[36], showing less diversity in Japan than in Korea (Table 5). TMRCA of O2b1-47z, and a star-cluster pattern in this study (Figure 3) and a previous study [13], all suggest the possible association of O2b1-47z with the peopling of Korea. However, because most of the Japanese O2b*-SRY465 and O2b1-47z samples were also in the core (or close to) of the cluster (Figure 3), it cannot exclude the possibility that the Japanese and the Koreans derive from the same proto-population outside of Korea (carrying these lineages) at roughly the same time. Thus, further studies of sufficient sampling in the vast East Asian region and genomewide genotyping should provide further insights. Investigative Genetics20112:10 |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 4, 2019 20:04:43 GMT

The "Horserider Thesis" and the Origins of Japan The 'horse-rider theory' is a controversial proposal that Japan was conquered around the 4th or 5th century CE by a culture from northern Asia to whom the horse was especially important. Although archaeological evidence and genetics point to a close relationship between Japan and East Asia, especially Korea, during that period, the idea that a full military takeover ever occurred is deemed unlikely by most historians. The exact relations between the young states of the region remain unclear, and the issue is further clouded by nationalist agendas and a persistent projection of modern concepts of statehood and nationality on geographical areas which at that time would not have existed. The 'horse-rider theory' (kiba minzoku setsu) was proposed by the historian Egami Namio in 1948 CE to explain the cultural and political development of Japan in the 4th and 5th century CE. Namio suggested that 'horse-riders', or more accurately, members of a culture originally from North Asia and then present in mainland Asia and the Korean peninsula for whom the horse was especially important, had travelled to Japan and spread their ideas and culture. The resulting conquest of the indigenous tribes in Japan led to a more unified country and what would become known as the Yamato state. Namio pointed to the archaeological evidence of large numbers of horse trappings discovered within Japanese tombs of the later Kofun Period (c. 250-538 CE) and their absence in the earlier part of the period as support for his theory.  A significant Korean influence on Japanese culture is attested by both archaeological and genetic evidence, which points to a migration of both people and ideas in the period in question. The Japanese Imperial family did mix with a Korean bloodline prior to the 7th century CE and the presence of an influential clan with Korean heritage, the Soga, is noted in the historical record. In addition, from the 4th century CE, friendly relations were established with the Korean state of Baekje (Paekche), which was firmly established by the late 3rd century CE and lasted until the conquest by its neighbour the Silla Kingdom in the mid-7th century CE. Baekje culture was exported abroad, especially via teachers, scholars, and artists travelling to Japan, and with them went Chinese culture such as classic Confucian texts but also elements of Korean-wide culture, for example, the court titles which closely resembled the bone rank system of the Silla kingdom or the wooden buildings constructed there by Korean architects and the large burial mounds of the period which are similar to those in Korea. The Japanese state, then known as Wa, also sent a 30,000-man army to aid the deposed Baekje rulers, but this was wiped out by a joint Silla-Tang naval force on the Paekchon (modern Kum) River c. 660 CE. In addition to these activities, the 4th and 5th century CE saw diplomatic missions and trading between Japan and China, further highlighting that the presence of continental cultural practices and goods in Japan does not necessarily mean they came via conquering invaders. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jan 5, 2019 18:14:14 GMT

That a Korean force actually invaded and conquered Japan so that it became no more than a vassal state is quite a different matter, then, from a cultural interaction between neighbouring states. It seems unlikely a conquest did actually occur, and some sources, including the Japanese c. 720 CE Nihon Shoki (Chronicle of Japan), controversially suggest the reverse and that Japan had established a colony in southern Korea in part of the Gaya (Kaya) confederation. This is now largely considered a tall tale by the Yamato court in order to increase its prestige as the reality is it lacked both the political and military where-with-all to carry out such a conquest. There was certainly an influx of Korean manufactured goods, weapons, and raw materials such as iron from Gaya but there is a notable absence of any new and distinct culture which one might expect to see following a military conquest. The historian M. J. Seth offers this plausible alternative explanation to a military invasion:  More likely, the peoples on both sides of the Korean Straits were related and interacted with each other. Evidence suggests that between 300 BCE and 300 CE large numbers of people migrated from the Korean peninsula to the Japanese archipelago, where they introduced rice culture, bronze and iron working, and other technologies. Thus rather than the existence of Korean and Japanese peoples there was a continuum of peoples and cultures. The Wa of western Japan, for example, may have lived on both sides of the Korean Straits, and they appeared to have close links with Kaya. It is even possible that the Wa and Kaya were the same ethnic group. The fact that Japanese and Korean political evolution followed similar patterns is too striking to be coincidental. (31-32) There was certainly an influx of Korean manufactured goods, weapons, and raw materials such as iron from Gaya but there is a notable absence of any new and distinct culture which one might expect to see following a military conquest. The historian M. J. Seth offers this plausible alternative explanation to a military invasion: More likely, the peoples on both sides of the Korean Straits were related and interacted with each other. Evidence suggests that between 300 BCE and 300 CE large numbers of people migrated from the Korean peninsula to the Japanese archipelago, where they introduced rice culture, bronze and iron working, and other technologies. Thus rather than the existence of Korean and Japanese peoples there was a continuum of peoples and cultures. The Wa of western Japan, for example, may have lived on both sides of the Korean Straits, and they appeared to have close links with Kaya. It is even possible that the Wa and Kaya were the same ethnic group. The fact that Japanese and Korean political evolution followed similar patterns is too striking to be coincidental. (31-32)  Japanese historians have traditionally sought to counter the 'horse-rider theory', and it has never been widely accepted in that country. Indeed, when Japan invaded Korea at the end of the 19th century CE, the government claimed that it was merely retaking possession of its former colony mentioned in the Nihon Shoki. More serious arguments against Namio’s theory have since developed and these include problems with and manipulation of the chronology to match an invasion with the dating of tombs and relevant artefacts, an incomplete consideration of all the archaeological evidence, the false assumption that tombs show a clear and distinct break between the period with or without horse paraphernalia and other continental goods in them, and an assumption that an agricultural society and/or ruling elite would not adopt the cultural practices and luxury goods of foreign peoples without military conquest. Korean historians and others have countered these arguments, insisting that a sudden cultural change is possible to identify in the archaeological and historical records and that the gradual nature of the change in tomb finds, tomb architecture, and political elites is greatly exaggerated. Some argue that linguistics and mythology both point to a mixing of the two cultures of Korea and Japan. Still others point to significant climate change which eventually resulted in a period of extended droughts around 400 CE and which motivated peoples to seek conditions more favourable to agriculture in the Japanese archipelago. No one, though, has as yet been able to provide direct evidence of how this transferral of culture occurred if not by peaceful means. |

|