Post by Admin on Nov 3, 2019 18:34:29 GMT

Historical Japanese emperors belonged to Y-DNA Haplogroup D1b1a2, which is the imperial Y-DNA lineage. Y-DNA haplogroups can be inherited from a father to his son and the old succession rule maintained this Y-DNA lineage for 2,000 years. Haplogroup D originated in East Africa along with Haplogroup E, which descended from the paragroup DE. D-M174 is dominant in Japan, the Andaman Islands, and Tibet, whereas E-M96 is relatively common in Africa and the Middle East.

The subclades of DE continue to confound investigators trying to reconstruct the migration of humans because, while they are common in Africa and East Asia, they are also largely absent between these two regions. As the paragroup DE(xD,E), including DE*, is extremely rare, the majority of DE male lines fall into subclades of either D-CTS3946 or E-M96. D-CTS3946 is suggested to have originated in Africa, though its most widespread subclade, D-M174, likely originated in Asia – the only place where D-M174 is now found. E-M96 is more likely to have originated in East Africa.

Abstract

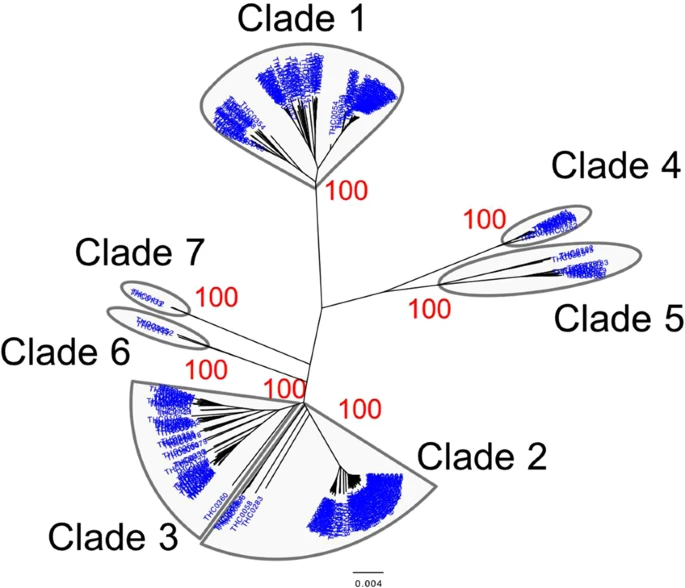

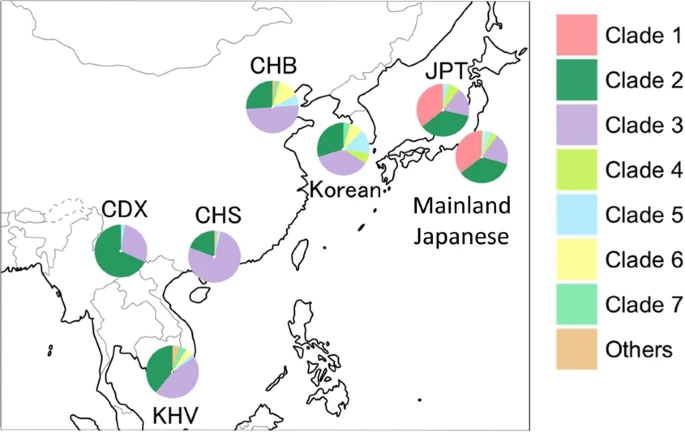

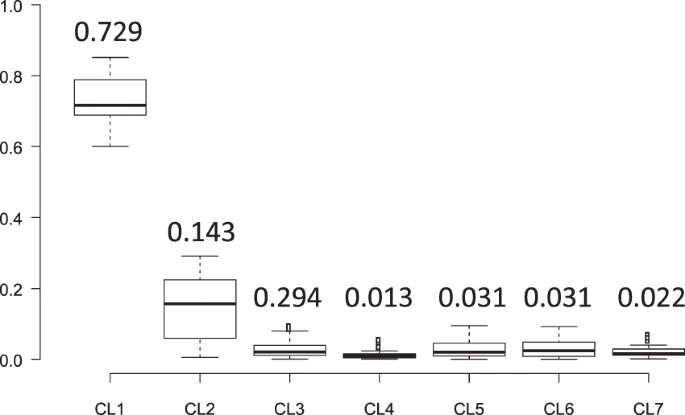

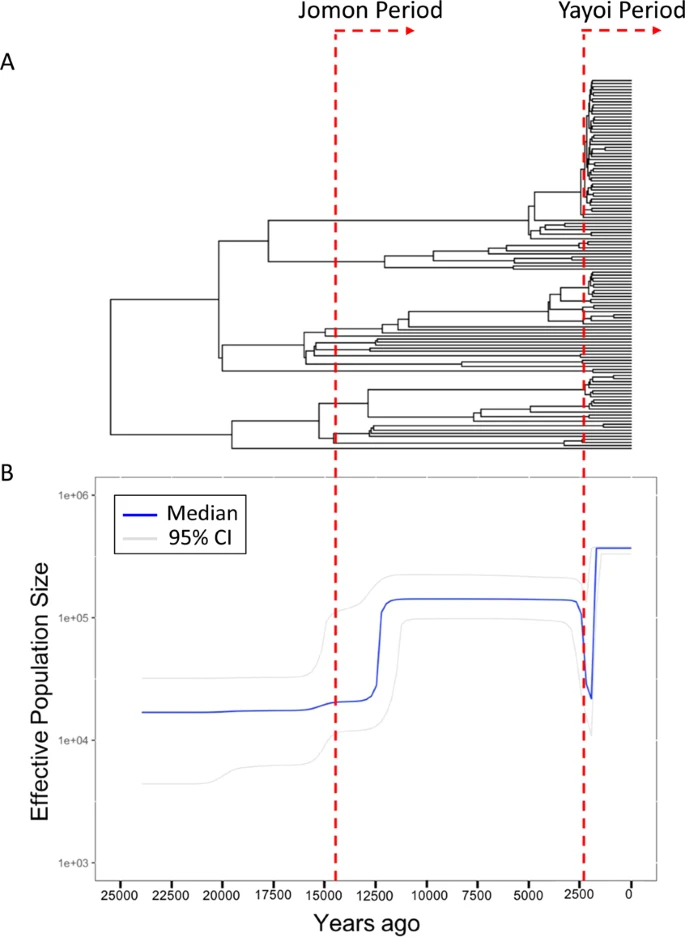

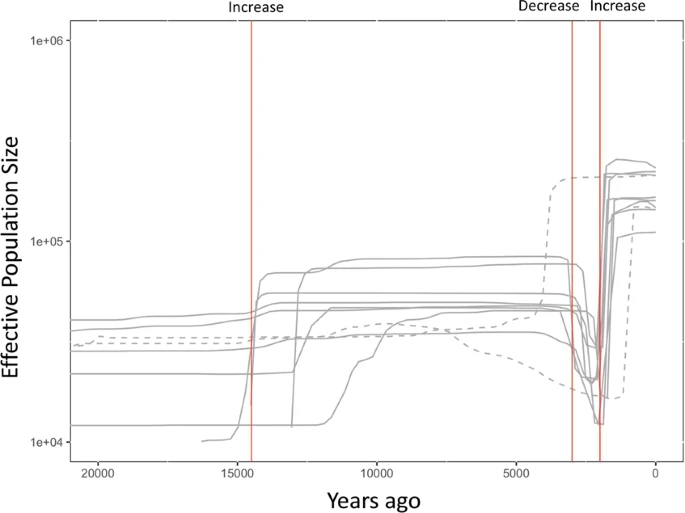

The Jomon and the Yayoi are considered to be the two major ancestral populations of the modern mainland Japanese. The Jomon people, who inhabited mainland Japan, admixed with Yayoi immigrants from the Asian continent. To investigate the population history in the Jomon period (14,500–2,300 years before present [YBP]), we analyzed whole Y-chromosome sequences of 345 Japanese males living in mainland Japan. A phylogenetic analysis of East Asian Y chromosomes identified a major clade (35.4% of mainland Japanese) consisting of only Japanese Y chromosomes, which seem to have originated from indigenous Jomon people. A Monte Carlo simulation indicated that ~70% of Jomon males had Y chromosomes in this clade. The Bayesian skyline plots of 122 Japanese Y chromosomes in the clade detected a marked decrease followed by a subsequent increase in the male population size from around the end of the Jomon period to the beginning of the Yayoi period (2,300 YBP). The colder climate in the Late to Final Jomon period may have resulted in critical shortages of food for the Jomon people, who were hunter-gatherers, and the rice farming introduced by Yayoi immigrants may have helped the population size of the Jomon people to recover.

Introduction

Archaeological studies have shown that the Japanese prehistory is divided into three periods: the Paleolithic period (older than 14,500 years before present [YBP]), the Jomon period (14,500-2,300 YBP), and the Yayoi period (2,300-1,700 YBP)1. One of the most important events in Japanese history is the transition from subsistence food production activities such as hunting and gathering to farming rice at the beginning of the Yayoi period. The advanced rice farming is thought to have been introduced to mainland Japan (we use the term “mainland Japan” to distinguish Honshu, Shikoku and Kyusyu from Hokkaido and Okinawa in this paper), inhabited by the Jomon people, by the Yayoi immigrants who came from the Asian continent.

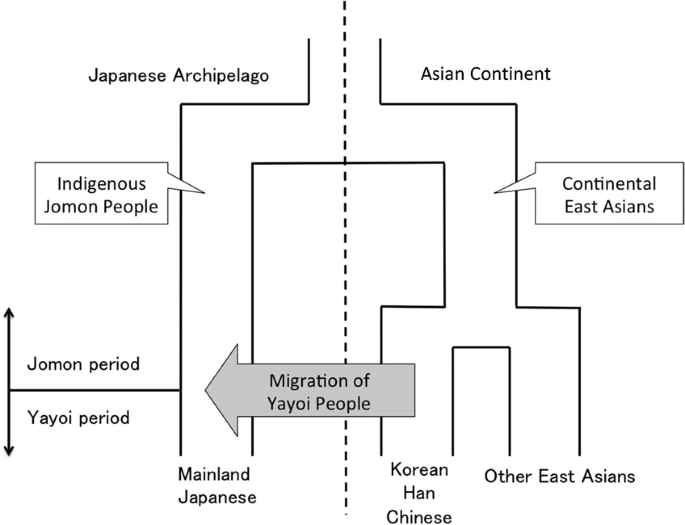

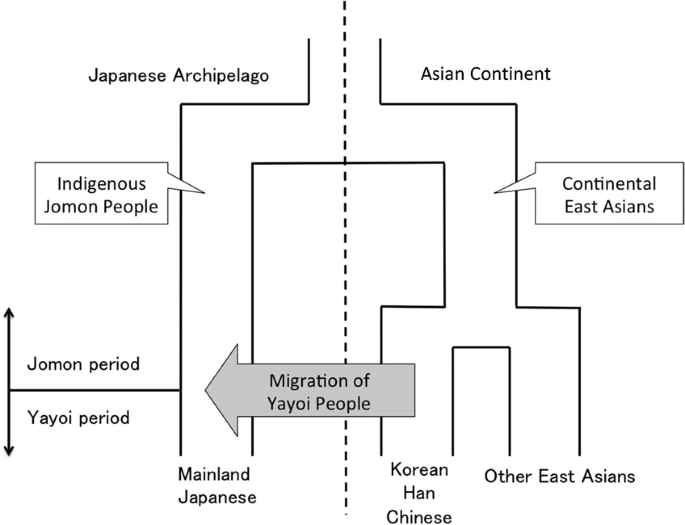

At present there are two minor populations and one major population in the Japanese archipelago: the Ainu who mainly live in Hokkaido (a minor population); the mainland Japanese (the major population); and the Ryukyuan who mainly live in Okinawa (a minor population). The prevailing hypothesis on the origins of the Japanese is “the dual structure model,2” where the present-day Japanese population is formed by an admixture between indigenous Jomon people and Yayoi immigrants who migrated from continental East Asia (Fig. 1). According to this model, modern mainland Japanese should have genomic components derived from both the Jomon people and those originating from the Yayoi immigrants. Genetic studies, using genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data, basically supported the above model3,4,5,6. A recent study of ancient DNA extracted from the remains of Jomon individuals who had lived in mainland Japan (Fukushima Prefecture) 3,000 YBP suggested that (1) the Jomon people were strongly divergent from the current East Asians (Fig. 1), (2) the Ainu people are most closely related to the Jomon people among the three Japanese populations, and (3) ~12% of the genomic components of the modern mainland Japanese were derived from the Jomon people7. Genetically, the mainland Japanese are closely related to Koreans, followed by Han Chinese, and finally by other Continental East Asians3. These findings suggest that a large number of Yayoi immigrants came mainly through the Korean Peninsula to mainland Japan, and the mainland Japanese still retain genomic components from the Jomon people. Thus, there is a possibility that the historical change in the population size of the historic Jomon people, who lived in mainland Japan, could be estimated from genomic data from the modern mainland Japanese.

Figure 1

In the current work, we estimated the change in population size of the Jomon people in the Late to Final Jomon period by using whole Y-chromosome sequences of Japanese males living in mainland Japan. Specifically, we identified a phylogenetic clade (hereinafter called “clade 1”) specific to Japanese Y chromosomes and largely divergent from ones attributable to the continental East Asians. Y chromosomes in clade 1 appeared to be derived from the Jomon people. The population frequency of clade 1 Y chromosomes was estimated to be ~70% in Jomon males. The Bayesian skyline plot (BSP)8 for Y chromosomes in clade 1 allowed us to infer the historical change in population size of the majority of the Jomon people. Our results suggested that the Jomon people underwent a major decrease in population size at the end of the Jomon period, with a recovery occurring soon after the beginning of the Yayoi period.

The subclades of DE continue to confound investigators trying to reconstruct the migration of humans because, while they are common in Africa and East Asia, they are also largely absent between these two regions. As the paragroup DE(xD,E), including DE*, is extremely rare, the majority of DE male lines fall into subclades of either D-CTS3946 or E-M96. D-CTS3946 is suggested to have originated in Africa, though its most widespread subclade, D-M174, likely originated in Asia – the only place where D-M174 is now found. E-M96 is more likely to have originated in East Africa.

Abstract

The Jomon and the Yayoi are considered to be the two major ancestral populations of the modern mainland Japanese. The Jomon people, who inhabited mainland Japan, admixed with Yayoi immigrants from the Asian continent. To investigate the population history in the Jomon period (14,500–2,300 years before present [YBP]), we analyzed whole Y-chromosome sequences of 345 Japanese males living in mainland Japan. A phylogenetic analysis of East Asian Y chromosomes identified a major clade (35.4% of mainland Japanese) consisting of only Japanese Y chromosomes, which seem to have originated from indigenous Jomon people. A Monte Carlo simulation indicated that ~70% of Jomon males had Y chromosomes in this clade. The Bayesian skyline plots of 122 Japanese Y chromosomes in the clade detected a marked decrease followed by a subsequent increase in the male population size from around the end of the Jomon period to the beginning of the Yayoi period (2,300 YBP). The colder climate in the Late to Final Jomon period may have resulted in critical shortages of food for the Jomon people, who were hunter-gatherers, and the rice farming introduced by Yayoi immigrants may have helped the population size of the Jomon people to recover.

Introduction

Archaeological studies have shown that the Japanese prehistory is divided into three periods: the Paleolithic period (older than 14,500 years before present [YBP]), the Jomon period (14,500-2,300 YBP), and the Yayoi period (2,300-1,700 YBP)1. One of the most important events in Japanese history is the transition from subsistence food production activities such as hunting and gathering to farming rice at the beginning of the Yayoi period. The advanced rice farming is thought to have been introduced to mainland Japan (we use the term “mainland Japan” to distinguish Honshu, Shikoku and Kyusyu from Hokkaido and Okinawa in this paper), inhabited by the Jomon people, by the Yayoi immigrants who came from the Asian continent.

At present there are two minor populations and one major population in the Japanese archipelago: the Ainu who mainly live in Hokkaido (a minor population); the mainland Japanese (the major population); and the Ryukyuan who mainly live in Okinawa (a minor population). The prevailing hypothesis on the origins of the Japanese is “the dual structure model,2” where the present-day Japanese population is formed by an admixture between indigenous Jomon people and Yayoi immigrants who migrated from continental East Asia (Fig. 1). According to this model, modern mainland Japanese should have genomic components derived from both the Jomon people and those originating from the Yayoi immigrants. Genetic studies, using genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data, basically supported the above model3,4,5,6. A recent study of ancient DNA extracted from the remains of Jomon individuals who had lived in mainland Japan (Fukushima Prefecture) 3,000 YBP suggested that (1) the Jomon people were strongly divergent from the current East Asians (Fig. 1), (2) the Ainu people are most closely related to the Jomon people among the three Japanese populations, and (3) ~12% of the genomic components of the modern mainland Japanese were derived from the Jomon people7. Genetically, the mainland Japanese are closely related to Koreans, followed by Han Chinese, and finally by other Continental East Asians3. These findings suggest that a large number of Yayoi immigrants came mainly through the Korean Peninsula to mainland Japan, and the mainland Japanese still retain genomic components from the Jomon people. Thus, there is a possibility that the historical change in the population size of the historic Jomon people, who lived in mainland Japan, could be estimated from genomic data from the modern mainland Japanese.

Figure 1

In the current work, we estimated the change in population size of the Jomon people in the Late to Final Jomon period by using whole Y-chromosome sequences of Japanese males living in mainland Japan. Specifically, we identified a phylogenetic clade (hereinafter called “clade 1”) specific to Japanese Y chromosomes and largely divergent from ones attributable to the continental East Asians. Y chromosomes in clade 1 appeared to be derived from the Jomon people. The population frequency of clade 1 Y chromosomes was estimated to be ~70% in Jomon males. The Bayesian skyline plot (BSP)8 for Y chromosomes in clade 1 allowed us to infer the historical change in population size of the majority of the Jomon people. Our results suggested that the Jomon people underwent a major decrease in population size at the end of the Jomon period, with a recovery occurring soon after the beginning of the Yayoi period.