Post by Admin on May 11, 2020 22:16:46 GMT

A single tooth is changing how archaeologists think about the history of human evolution.

The tooth, a molar, is one of the last remnants of the earliest modern humans found in Europe, according to two papers published Monday by an international team of archaeologists, who found it among human remains, stone and bone tools, and pendants made from cave bear teeth, in Bulgaria’s labyrinthine Bacho Kiro cave.

“This is much older than anything else that we have found so far from modern humans in Europe,” said Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology at Leipzig in Germany, who led the team.

The molar is the largest surviving bone fragment from a group of very early Homo sapiens that was dated to between 44,000 and 46,000 years ago.

The papers on the discoveries were published in the science journal Nature and in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

They push back the earliest confirmed arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe, and show they somehow shared the land for thousands of years with the heavily-built Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) who were already there.

The finds also resolve a debate about distinctive tools and personal ornaments known as Bachokirian, after the cave.

Similar items made by Neanderthals have been found elsewhere. But the new finds indicate those Neanderthals adopted the new ways of making them from early Homo sapiens.

Evidence from other sites suggests the people at Bacho Kiro cave were part of a “pioneer” wave of Homo sapiens that entered southern and central Europe up to 47,000 years ago from southwest Asia, Hublin said.

Their arrival was up to 8,000 years earlier than a wave of Homo sapiens that eventually spread across western Europe, and replaced the last Neanderthals about 39,000 years ago.

Homo sapiens also replaced other groups of early humans, such as the Denisovans who had populated much of Asia, at around the same time, he said.

Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria

Jean-Jacques Hublin, Nikolay Sirakov, […]Tsenka Tsanova

Abstract

The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition in Europe witnessed the replacement and partial absorption of local Neanderthal populations by Homo sapiens populations of African origin1. However, this process probably varied across regions and its details remain largely unknown. In particular, the duration of chronological overlap between the two groups is much debated, as are the implications of this overlap for the nature of the biological and cultural interactions between Neanderthals and H. sapiens. Here we report the discovery and direct dating of human remains found in association with Initial Upper Palaeolithic artefacts2, from excavations at Bacho Kiro Cave (Bulgaria). Morphological analysis of a tooth and mitochondrial DNA from several hominin bone fragments, identified through proteomic screening, assign these finds to H. sapiens and link the expansion of Initial Upper Palaeolithic technologies with the spread of H. sapiens into the mid-latitudes of Eurasia before 45 thousand years ago3. The excavations yielded a wealth of bone artefacts, including pendants manufactured from cave bear teeth that are reminiscent of those later produced by the last Neanderthals of western Europe4,5,6. These finds are consistent with models based on the arrival of multiple waves of H. sapiens into Europe coming into contact with declining Neanderthal populations7,8.

A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria

Helen Fewlass, Sahra Talamo, Lukas Wacker, Bernd Kromer, Thibaut Tuna, Yoann Fagault, Edouard Bard, Shannon P. McPherron, Vera Aldeias, Raquel Maria, Naomi L. Martisius, Lindsay Paskulin, Zeljko Rezek, Virginie Sinet-Mathiot, Svoboda Sirakova, Geoffrey M. Smith, Rosen Spasov, Frido Welker, Nikolay Sirakov, Tsenka Tsanova & Jean-Jacques Hublin

Abstract

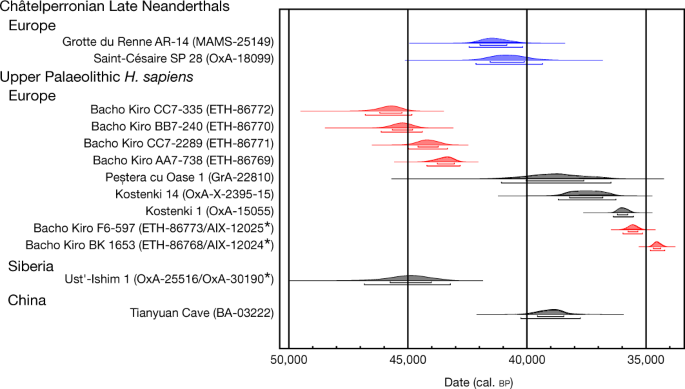

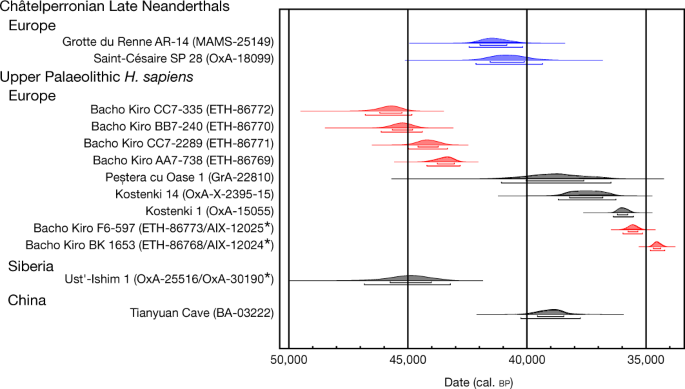

The stratigraphy at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria, spans the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition, including an Initial Upper Palaeolithic (IUP) assemblage argued to represent the earliest arrival of Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens in Europe. We applied the latest techniques in 14C dating to an extensive dataset of newly excavated animal and human bones to produce a robust, high-precision radiocarbon chronology for the site. At the base of the stratigraphy, the Middle Palaeolithic (MP) occupation dates to >51,000 yr BP. A chronological gap of over 3,000 years separates the MP occupation from the occupation of the cave by H. sapiens, which extends to 34,000 cal BP. The extensive IUP assemblage, now associated with directly dated H. sapiens fossils at this site, securely dates to 45,820–43,650 cal BP (95.4% probability), probably beginning from 46,940 cal BP (95.4% probability). The results provide chronological context for the early occupation of Europe by Upper Palaeolithic H. sapiens.

The tooth, a molar, is one of the last remnants of the earliest modern humans found in Europe, according to two papers published Monday by an international team of archaeologists, who found it among human remains, stone and bone tools, and pendants made from cave bear teeth, in Bulgaria’s labyrinthine Bacho Kiro cave.

“This is much older than anything else that we have found so far from modern humans in Europe,” said Jean-Jacques Hublin, a paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology at Leipzig in Germany, who led the team.

The molar is the largest surviving bone fragment from a group of very early Homo sapiens that was dated to between 44,000 and 46,000 years ago.

The papers on the discoveries were published in the science journal Nature and in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

They push back the earliest confirmed arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe, and show they somehow shared the land for thousands of years with the heavily-built Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) who were already there.

The finds also resolve a debate about distinctive tools and personal ornaments known as Bachokirian, after the cave.

Similar items made by Neanderthals have been found elsewhere. But the new finds indicate those Neanderthals adopted the new ways of making them from early Homo sapiens.

Evidence from other sites suggests the people at Bacho Kiro cave were part of a “pioneer” wave of Homo sapiens that entered southern and central Europe up to 47,000 years ago from southwest Asia, Hublin said.

Their arrival was up to 8,000 years earlier than a wave of Homo sapiens that eventually spread across western Europe, and replaced the last Neanderthals about 39,000 years ago.

Homo sapiens also replaced other groups of early humans, such as the Denisovans who had populated much of Asia, at around the same time, he said.

Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria

Jean-Jacques Hublin, Nikolay Sirakov, […]Tsenka Tsanova

Abstract

The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition in Europe witnessed the replacement and partial absorption of local Neanderthal populations by Homo sapiens populations of African origin1. However, this process probably varied across regions and its details remain largely unknown. In particular, the duration of chronological overlap between the two groups is much debated, as are the implications of this overlap for the nature of the biological and cultural interactions between Neanderthals and H. sapiens. Here we report the discovery and direct dating of human remains found in association with Initial Upper Palaeolithic artefacts2, from excavations at Bacho Kiro Cave (Bulgaria). Morphological analysis of a tooth and mitochondrial DNA from several hominin bone fragments, identified through proteomic screening, assign these finds to H. sapiens and link the expansion of Initial Upper Palaeolithic technologies with the spread of H. sapiens into the mid-latitudes of Eurasia before 45 thousand years ago3. The excavations yielded a wealth of bone artefacts, including pendants manufactured from cave bear teeth that are reminiscent of those later produced by the last Neanderthals of western Europe4,5,6. These finds are consistent with models based on the arrival of multiple waves of H. sapiens into Europe coming into contact with declining Neanderthal populations7,8.

A 14C chronology for the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria

Helen Fewlass, Sahra Talamo, Lukas Wacker, Bernd Kromer, Thibaut Tuna, Yoann Fagault, Edouard Bard, Shannon P. McPherron, Vera Aldeias, Raquel Maria, Naomi L. Martisius, Lindsay Paskulin, Zeljko Rezek, Virginie Sinet-Mathiot, Svoboda Sirakova, Geoffrey M. Smith, Rosen Spasov, Frido Welker, Nikolay Sirakov, Tsenka Tsanova & Jean-Jacques Hublin

Abstract

The stratigraphy at Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria, spans the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic transition, including an Initial Upper Palaeolithic (IUP) assemblage argued to represent the earliest arrival of Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens in Europe. We applied the latest techniques in 14C dating to an extensive dataset of newly excavated animal and human bones to produce a robust, high-precision radiocarbon chronology for the site. At the base of the stratigraphy, the Middle Palaeolithic (MP) occupation dates to >51,000 yr BP. A chronological gap of over 3,000 years separates the MP occupation from the occupation of the cave by H. sapiens, which extends to 34,000 cal BP. The extensive IUP assemblage, now associated with directly dated H. sapiens fossils at this site, securely dates to 45,820–43,650 cal BP (95.4% probability), probably beginning from 46,940 cal BP (95.4% probability). The results provide chronological context for the early occupation of Europe by Upper Palaeolithic H. sapiens.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ad/87/ad873224-ef9b-4b54-9f8b-d471b4609f26/2009-49418-h-heidelbergensis-jgurche_web.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/e3/7f/e37fea5e-d63a-4e07-8032-17e74e539d77/figure-11_web_2.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/0b/ca/0bcae72f-e72d-4bde-be7c-863712b8b68e/msa-stone-tools-and-pigments-white-background_web.jpg)