Post by Admin on Dec 12, 2019 18:32:10 GMT

INTRODUCTION

Full language is unique to and universal in humans, where it is universally transmitted by vocal speech. Animals do communicate in various ways, including with vocal calls, but the structural complexity, flexibility, and integration of speech and language in humans are vastly greater than anything found in other species. Understanding the gulf between the human and animal systems and specifically how the modern human system, language, emerged evolutionarily through extinct hominins from the lesser systems of our hominid ancestors has been called the hardest problem in science (1). Our aim in this article is to present both a schematic history and the state of the art in research on vocal communication of nonhuman primates to better illuminate the emergence of human speech—a limited but crucial component of the broader topic of language emergence—by using a comparison of phylogeny and ontogeny and to add a contribution that has only recently become possible.

The study of speech evolution is necessarily multidisciplinary, involving at a minimum paleoanthropology, primatology, and speech science, itself already a conglomeration of phonetics, anatomy, acoustics, human development, and more. The long process of interweaving these typically independent disciplines over such a complex research problem to build a consensus will inevitably entail controversy as well as progress, but analyzing scientific controversies before they are resolved allows us to observe “science in action” (2): how practicing researchers collect data, develop hypotheses, advance interpretations, and commit to them before theories reach a general consensus. The nature and history of that interweaving is the foundation of this article. We hope that readers will find it instructive to reflect on the paths and processes involved.

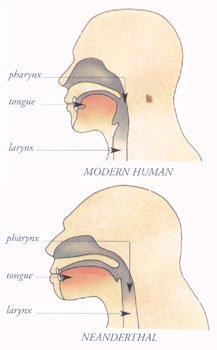

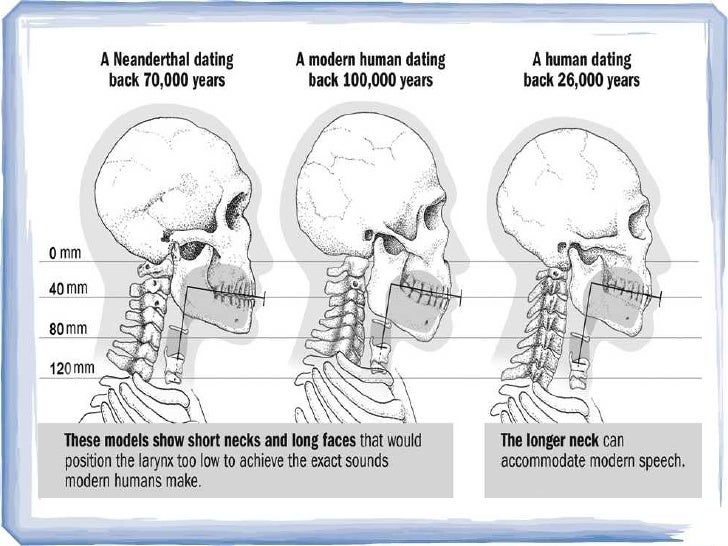

Specifically, in the “The development of research in speech evolution and the LDT” section, we present the beginnings of speech evolution research with the laryngeal descent theory (LDT), which very strongly affected the nature of research on this topic with its claim that only modern humans could produce fully contrasting vowel qualities. In the “LD is not uniquely human: Ethology, primatology, bioacoustics, and primate and animal communication” section, we discuss how ethology and primatology addressed primate communication within the LDT framework yet progressively accumulated evidence incompatible with LDT. In the “Vowel qualities can contrast without a low larynx: Fundamentals of speech acoustics” section, we explain the major elements of articulatory and acoustic analysis of speech production and show how they strongly imply that laryngeal descent (LD) is not required to produce contrasting vowels. In the “Uniform tubes cannot explain primate vocalizations: The acoustic capacities of nonhuman primates” section, we present a large amount of data on nonhuman primate vocalizations, showing that they do involve contrasting vowel qualities. Last, in the “Lessons learned from the LD controversy” section, we analyze the lessons learned and some new overall perspectives on the problem of speech emergence.

More generally, our intent is to fully examine the current state of knowledge about the evolutionary roots of human vowel production. Here, we will not enter into the vigorous and important debates on other aspects of language evolution, including syntax, lexicon, gesture, and neurolinguistics, nor do we address other crucial aspects of speech, such as consonants, phonological representations, syllabic organization, speech perception, or neuromuscular control. At least two reasons justify our tight focus on vowel production: First, vowels are the core of speech production and are required to effectively transmit consonantal acoustics, which together enable a phonologically encoded lexicon, which is then subject to syntax. Thus, vowel production enjoys logical primacy, because no other aspect of spoken language has any utility until the articulatory ability to produce vowels is established. Second, LDT’s claim that only fully modern humans can produce contrasting vowels has been argued as restricting all aspects of language emergence to the past 200,000 years, thus bolstering claims of the flowering of full human language within the past 100,000 to 70,000 years (3). If LDT is refuted, and contrasting vowel qualities were available earlier, that opens for reexamination the time frames for emergence of all subsequent aspects of language. Thus, in our view, these questions of vowel production are not trivial, but foundational, for the field of language evolution.

Full language is unique to and universal in humans, where it is universally transmitted by vocal speech. Animals do communicate in various ways, including with vocal calls, but the structural complexity, flexibility, and integration of speech and language in humans are vastly greater than anything found in other species. Understanding the gulf between the human and animal systems and specifically how the modern human system, language, emerged evolutionarily through extinct hominins from the lesser systems of our hominid ancestors has been called the hardest problem in science (1). Our aim in this article is to present both a schematic history and the state of the art in research on vocal communication of nonhuman primates to better illuminate the emergence of human speech—a limited but crucial component of the broader topic of language emergence—by using a comparison of phylogeny and ontogeny and to add a contribution that has only recently become possible.

The study of speech evolution is necessarily multidisciplinary, involving at a minimum paleoanthropology, primatology, and speech science, itself already a conglomeration of phonetics, anatomy, acoustics, human development, and more. The long process of interweaving these typically independent disciplines over such a complex research problem to build a consensus will inevitably entail controversy as well as progress, but analyzing scientific controversies before they are resolved allows us to observe “science in action” (2): how practicing researchers collect data, develop hypotheses, advance interpretations, and commit to them before theories reach a general consensus. The nature and history of that interweaving is the foundation of this article. We hope that readers will find it instructive to reflect on the paths and processes involved.

Specifically, in the “The development of research in speech evolution and the LDT” section, we present the beginnings of speech evolution research with the laryngeal descent theory (LDT), which very strongly affected the nature of research on this topic with its claim that only modern humans could produce fully contrasting vowel qualities. In the “LD is not uniquely human: Ethology, primatology, bioacoustics, and primate and animal communication” section, we discuss how ethology and primatology addressed primate communication within the LDT framework yet progressively accumulated evidence incompatible with LDT. In the “Vowel qualities can contrast without a low larynx: Fundamentals of speech acoustics” section, we explain the major elements of articulatory and acoustic analysis of speech production and show how they strongly imply that laryngeal descent (LD) is not required to produce contrasting vowels. In the “Uniform tubes cannot explain primate vocalizations: The acoustic capacities of nonhuman primates” section, we present a large amount of data on nonhuman primate vocalizations, showing that they do involve contrasting vowel qualities. Last, in the “Lessons learned from the LD controversy” section, we analyze the lessons learned and some new overall perspectives on the problem of speech emergence.

More generally, our intent is to fully examine the current state of knowledge about the evolutionary roots of human vowel production. Here, we will not enter into the vigorous and important debates on other aspects of language evolution, including syntax, lexicon, gesture, and neurolinguistics, nor do we address other crucial aspects of speech, such as consonants, phonological representations, syllabic organization, speech perception, or neuromuscular control. At least two reasons justify our tight focus on vowel production: First, vowels are the core of speech production and are required to effectively transmit consonantal acoustics, which together enable a phonologically encoded lexicon, which is then subject to syntax. Thus, vowel production enjoys logical primacy, because no other aspect of spoken language has any utility until the articulatory ability to produce vowels is established. Second, LDT’s claim that only fully modern humans can produce contrasting vowels has been argued as restricting all aspects of language emergence to the past 200,000 years, thus bolstering claims of the flowering of full human language within the past 100,000 to 70,000 years (3). If LDT is refuted, and contrasting vowel qualities were available earlier, that opens for reexamination the time frames for emergence of all subsequent aspects of language. Thus, in our view, these questions of vowel production are not trivial, but foundational, for the field of language evolution.