Post by Admin on Feb 14, 2024 20:55:35 GMT

Insights into sex bias, biological kinship and marital practices

Studies have shown that in some regions of Europe—like the Iberian Peninsula, Central Europe and Britain—the large-scale gene flow associated with the Eurasian Steppe during the BA resulted in the prevalence of the Y chromosome R1a and R1b haplogroups28 or even involved male-biased admixture33,39,40. For the Aegean, we also estimated a significantly lower WES-ancestry proportion on the X chromosomes of the male individuals compared to most of the autosomes, which is consistent with male-biased admixture (Extended Data Fig. 3). However, only four out of the 30 male individuals dating post-sixteenth century BC (LBA and IA) carry the R1b1a1b Y haplogroup. The remaining—as well as the EBA/MBA ones—attest to the high prevalence of Y haplogroups J and G/G2 (39 and 10 out of 59, respectively; Supplementary Table 2). These were already present in Early Holocene Iran/Caucasus and among Anatolian and European farmers41,42,43,44,45 and very common in the Chalcolithic Anatolia and the Levant as well42,46,47, further highlighting the importance of the contacts between the Aegean and southwest Asian populations since the Early Neolithic.

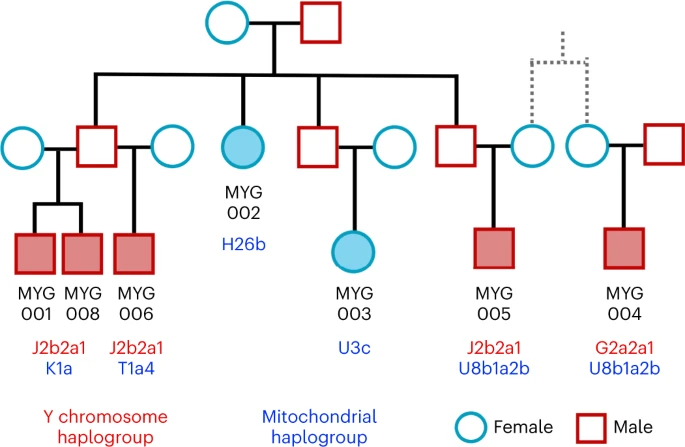

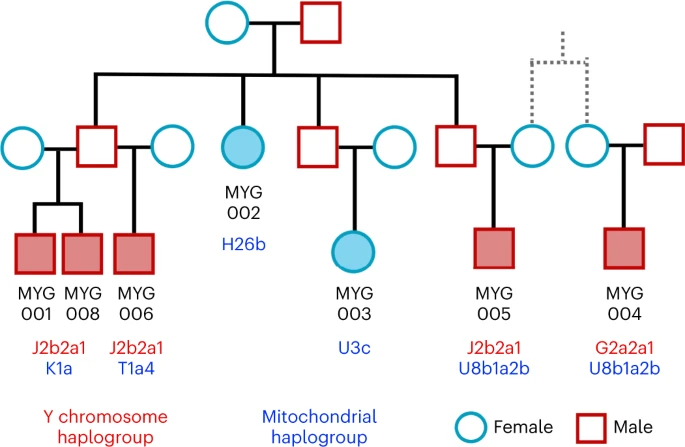

Biological relatedness and its representation in prehistoric collective burials has been poorly understood in the Aegean. Here, we present the first evidence for representation of biologically kin groups from a collective intramural infant grave dating to the LBA—a type of burial which existed since the Neolithic Aegean but became more common since the MBA48,49. Located within the Mycenaean (LBA) settlement in Mygdalia, a small cist grave was the primary inhumation of at least eight perinatal infants and one of the six child burials under the houses of the settlement (Supplementary Note 1). By estimating the degree of relatedness among seven of these infants (Methods; Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 3) and assigning the uniparental haplogroups (Supplementary Table 2), the relationship of the infants could be resolved in a single extended family tree whereby the six infants were the children and grandchildren of one couple (Fig. 5). The seventh individual (MYG004) was not a direct offspring of this family but related to MYG005 in the third degree through the maternal line, plausibly as first cousins.

Fig. 5: Reconstruction of the family tree for the infants from the burial in Mygdalia (MYG; solid colour shapes).

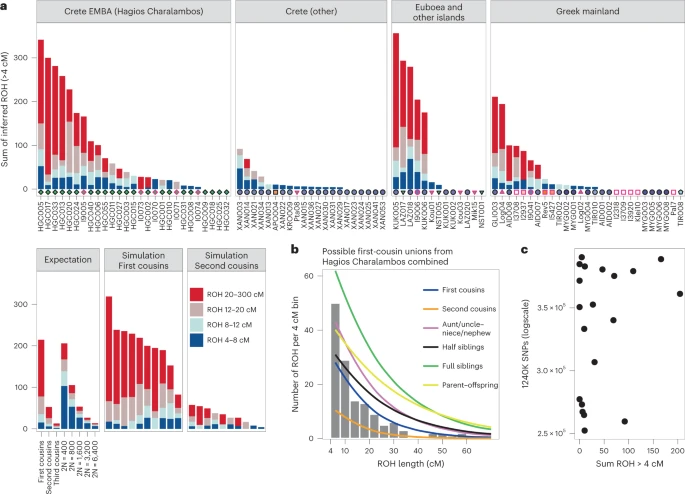

Additional evidence of biological relatedness comes from Aidonia, where pairs of first- to third-degree relatives were determined among individuals buried within the three chamber tombs and the ossuary of Hagios Charalambos at the Lasithi plateau (Supplementary Note 1 and Extended Data Fig. 4). The individuals studied from Hagios Charalambos represent a secondary deposition of intermingled skeletons but were all unearthed from a particular section of the cave (Supplementary Note 1). Besides some pairs of close relatives (first to second degree), many pairs represent distant relatives. In addition to this high frequency of distant genetic relatedness, we also report extraordinarily high levels of consanguinity (~50% of the 27 individuals) estimated from the runs of homozygosity (ROH) by performing hapROH on the genotyping data50 (Fig. 6a; Methods). The individual ROH histograms matched more with the expectations for parents being related to the degree of first cousins, half-siblings and aunt/uncle–nephew/niece (Extended Data Fig. 5). However, given the stochastic nature of genetic recombination and the often-compromised coverage of ancient samples, one individual’s genome might only noisily match the expectations. Therefore, we combined the possible first-cousins unions cases and the cumulative histogram this produced favoured the parental relationship of first cousins against other scenarios (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 6). Coupling the evidence for frequent distant relatives and cousin–cousin unions suggests that those individuals formed a small endogamous community that regularly practiced first-cousin intermarriages.

Studies have shown that in some regions of Europe—like the Iberian Peninsula, Central Europe and Britain—the large-scale gene flow associated with the Eurasian Steppe during the BA resulted in the prevalence of the Y chromosome R1a and R1b haplogroups28 or even involved male-biased admixture33,39,40. For the Aegean, we also estimated a significantly lower WES-ancestry proportion on the X chromosomes of the male individuals compared to most of the autosomes, which is consistent with male-biased admixture (Extended Data Fig. 3). However, only four out of the 30 male individuals dating post-sixteenth century BC (LBA and IA) carry the R1b1a1b Y haplogroup. The remaining—as well as the EBA/MBA ones—attest to the high prevalence of Y haplogroups J and G/G2 (39 and 10 out of 59, respectively; Supplementary Table 2). These were already present in Early Holocene Iran/Caucasus and among Anatolian and European farmers41,42,43,44,45 and very common in the Chalcolithic Anatolia and the Levant as well42,46,47, further highlighting the importance of the contacts between the Aegean and southwest Asian populations since the Early Neolithic.

Biological relatedness and its representation in prehistoric collective burials has been poorly understood in the Aegean. Here, we present the first evidence for representation of biologically kin groups from a collective intramural infant grave dating to the LBA—a type of burial which existed since the Neolithic Aegean but became more common since the MBA48,49. Located within the Mycenaean (LBA) settlement in Mygdalia, a small cist grave was the primary inhumation of at least eight perinatal infants and one of the six child burials under the houses of the settlement (Supplementary Note 1). By estimating the degree of relatedness among seven of these infants (Methods; Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 3) and assigning the uniparental haplogroups (Supplementary Table 2), the relationship of the infants could be resolved in a single extended family tree whereby the six infants were the children and grandchildren of one couple (Fig. 5). The seventh individual (MYG004) was not a direct offspring of this family but related to MYG005 in the third degree through the maternal line, plausibly as first cousins.

Fig. 5: Reconstruction of the family tree for the infants from the burial in Mygdalia (MYG; solid colour shapes).

Additional evidence of biological relatedness comes from Aidonia, where pairs of first- to third-degree relatives were determined among individuals buried within the three chamber tombs and the ossuary of Hagios Charalambos at the Lasithi plateau (Supplementary Note 1 and Extended Data Fig. 4). The individuals studied from Hagios Charalambos represent a secondary deposition of intermingled skeletons but were all unearthed from a particular section of the cave (Supplementary Note 1). Besides some pairs of close relatives (first to second degree), many pairs represent distant relatives. In addition to this high frequency of distant genetic relatedness, we also report extraordinarily high levels of consanguinity (~50% of the 27 individuals) estimated from the runs of homozygosity (ROH) by performing hapROH on the genotyping data50 (Fig. 6a; Methods). The individual ROH histograms matched more with the expectations for parents being related to the degree of first cousins, half-siblings and aunt/uncle–nephew/niece (Extended Data Fig. 5). However, given the stochastic nature of genetic recombination and the often-compromised coverage of ancient samples, one individual’s genome might only noisily match the expectations. Therefore, we combined the possible first-cousins unions cases and the cumulative histogram this produced favoured the parental relationship of first cousins against other scenarios (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 6). Coupling the evidence for frequent distant relatives and cousin–cousin unions suggests that those individuals formed a small endogamous community that regularly practiced first-cousin intermarriages.