Post by Admin on Jun 22, 2020 4:43:44 GMT

Ethnicity, critical care admission and invasive mechanical ventilation

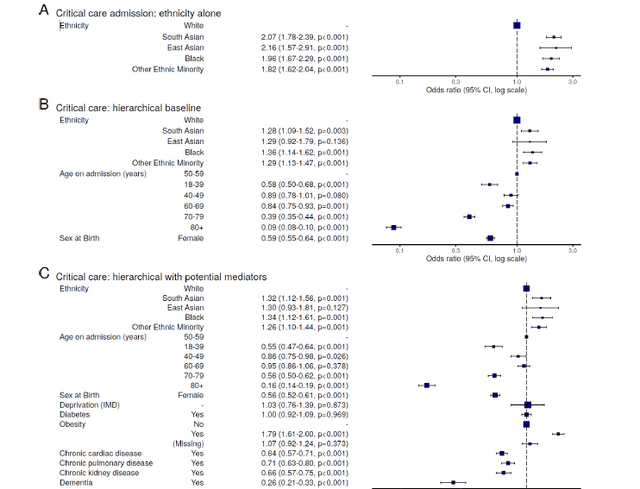

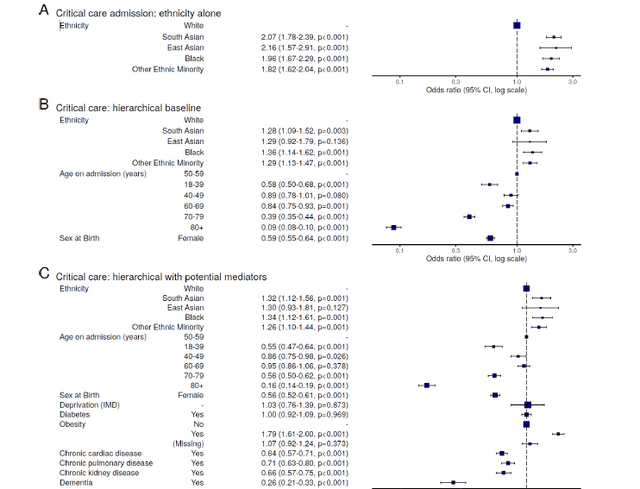

Overall, 4,353 patients (14%) were admitted to a critical care facility (figure 4A). On unadjusted analysis, White individuals (n=3,258, 13%) were less likely to be admitted to critical care than South Asian (293, 21%), East Asian (64, 24%), Black (241, 22%), or Other Ethnic Minority (497, 21%) people.

In models accounting for age, sex, and location (figure 5B), these associations persisted in South Asian (odds ratio 1.28, 95% confidence interval 1.09 to 1.59), Black (1.36, 1.14 to 1.62), and Other Ethnic Minority (1.29, 1.13 to 1.47) (table E3) groups. No meaningful change in these estimates was seen with the sequential introduction of potential mediators including deprivation and comorbidities (diabetes, obesity, chronic cardiac disease, non-asthmatic chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and dementia) (figure

5C).

Similar findings were found in analyses of invasive mechanical ventilation (Figure E2, table E3).

Ethnicity and survival from COVID-19

In analyses not accounting for age and sex differences between ethnic groups, in-hospital mortality occurred more frequently in the White group compared to the Ethnic Minorities (figure 4C, 6A). A sensitivity analysis excluding patients admitted in the most recent four weeks showed the same results (figure 4D).

However, in models accounting for age, sex, and location, evidence of higher mortality was seen in South Asian (hazard ratio 1.19, 1.05 to 1.36), but not East Asian (1.00, 0.74 to 1.35), Black (1.05, 0.91 to 1.21) or Other Ethnic Minority (0.99, 0.89 to 1.10) groups, compared to White group (figure 6B; table E5). No interaction was seen between ethnicity and age nor ethnicity and sex. Similar results were seen in alternative models of competing risks (table E10) and in models replaced in the ten multiple imputation sets (figure E3).

All associated comorbidities were explored as potential mediators of the apparent association between South Asian ethnicity and an increased hazard of death. Comorbidities associated with death in age- and sexadjusted analysis were explored (table E11 to E15). Of these, diabetes (hazard ratio 2.29, 1.99 to 2.62, P < 0.001) and chronic kidney disease (1.66, 1.38 to 2.00, P < 0.001) had strong positive associations with South Asian ethnicity (figure 2).

A significant mediation effect (total natural indirect) of diabetes was found (hazard ratio 1.03, 1.02 to 1.04, P < 0.001; table E16) representing 17.8% (8.9 to 65.7, P = 0.009; table E17) of the total effect of South Asian ethnicity on mortality (figure 7). Chronic kidney disease did not contribute significantly beyond the addition of diabetes to the model. Finally, to explore the relationship between age, diabetes and South Asian ethnicity, a Cox model was fitted including a three-way interaction (Figure 7B). The excess mortality was seen only in older South Asian patients. The association between diabetes and mortality was strongest in younger patients, compared with older. The diabetes effect was as strong in white patients, but the

prevalence of diabetes higher in the South Asian group.

As reported in our earlier analysis, extreme elderly age and the presence of comorbidities were associated

with a lower likelihood of critical care admission, suggesting advanced care planning decisions on the ward.4

While this may have disproportionately affected patients in the White group who were significantly older

with more cardiac and respiratory disease, the increased likelihood of critical care admission and IMV in

Ethnic Minorities persisted after adjustment. This may reflect an increased severity of disease in multiple

Ethnic Minority populations, but falling short of significantly increased mortality in many.

Our finding of significantly increased mortality in the South Asian group is in agreement with reports which

found that people from Asian and Black ethnic groups were at increased risk of in-hospital death from

COVID-19, and that this was only partially attributable to pre-existing clinical risk factors or deprivation.8,18,35

We add an important and detailed picture of differences in characteristics of ethnic groups in hospital. The

prevalence of diabetes is also striking at around 40% in South Asian and Black patients and the mediation of

the mortality effect by diabetes is important. This appeared independent of chronic cardiac disease and

chronic kidney disease and is likely to be due to the multitude of other negative health associations carried

by the condition.

What of the increased mortality in South Asian patients left unexplained? Our models did not account well

for wide socioeconomic determinants of outcome, as well as nuance in the comorbidity data. Socioeconomic

inequalities contribute to differential exposure to infection, differential vulnerability following infection, and

differential consequences of infection as well as control measures.36 In other studies, at Local Authority

district level, the districts with a greater proportion of residents from non-White groups experienced higher

COVID19 mortality rates, as did districts with a greater proportion of residents experiencing deprivation

from low income.19 We did not find that deprivation at the level of the hospital was a significant predictor of

time to hospital admission or severity of illness in hospital, however, aggregation of deprivation at hospital

level masks individual socioeconomic effects. Future studies should examine the disaggregated effects

where possible.

Why was excess mortality not apparent among our Black population, as others have reported?8 It seems

unlikely this group are dying disproportionately in community compared with hospital settings, so any true

effect should be visible in our cohort. Given that our study includes 40% of the UK hospitalised population,

selection bias is clearly a possibility. On the other hand, it is possible that the estimates in our study are

correct, given that some population-level reports rely on older census data as the denominator. Our ongoing

work includes linking our dataset widely to better understand the place of the in-hospital stay as part

of the full patient journey.

Overall, 4,353 patients (14%) were admitted to a critical care facility (figure 4A). On unadjusted analysis, White individuals (n=3,258, 13%) were less likely to be admitted to critical care than South Asian (293, 21%), East Asian (64, 24%), Black (241, 22%), or Other Ethnic Minority (497, 21%) people.

In models accounting for age, sex, and location (figure 5B), these associations persisted in South Asian (odds ratio 1.28, 95% confidence interval 1.09 to 1.59), Black (1.36, 1.14 to 1.62), and Other Ethnic Minority (1.29, 1.13 to 1.47) (table E3) groups. No meaningful change in these estimates was seen with the sequential introduction of potential mediators including deprivation and comorbidities (diabetes, obesity, chronic cardiac disease, non-asthmatic chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and dementia) (figure

5C).

Similar findings were found in analyses of invasive mechanical ventilation (Figure E2, table E3).

Ethnicity and survival from COVID-19

In analyses not accounting for age and sex differences between ethnic groups, in-hospital mortality occurred more frequently in the White group compared to the Ethnic Minorities (figure 4C, 6A). A sensitivity analysis excluding patients admitted in the most recent four weeks showed the same results (figure 4D).

However, in models accounting for age, sex, and location, evidence of higher mortality was seen in South Asian (hazard ratio 1.19, 1.05 to 1.36), but not East Asian (1.00, 0.74 to 1.35), Black (1.05, 0.91 to 1.21) or Other Ethnic Minority (0.99, 0.89 to 1.10) groups, compared to White group (figure 6B; table E5). No interaction was seen between ethnicity and age nor ethnicity and sex. Similar results were seen in alternative models of competing risks (table E10) and in models replaced in the ten multiple imputation sets (figure E3).

All associated comorbidities were explored as potential mediators of the apparent association between South Asian ethnicity and an increased hazard of death. Comorbidities associated with death in age- and sexadjusted analysis were explored (table E11 to E15). Of these, diabetes (hazard ratio 2.29, 1.99 to 2.62, P < 0.001) and chronic kidney disease (1.66, 1.38 to 2.00, P < 0.001) had strong positive associations with South Asian ethnicity (figure 2).

A significant mediation effect (total natural indirect) of diabetes was found (hazard ratio 1.03, 1.02 to 1.04, P < 0.001; table E16) representing 17.8% (8.9 to 65.7, P = 0.009; table E17) of the total effect of South Asian ethnicity on mortality (figure 7). Chronic kidney disease did not contribute significantly beyond the addition of diabetes to the model. Finally, to explore the relationship between age, diabetes and South Asian ethnicity, a Cox model was fitted including a three-way interaction (Figure 7B). The excess mortality was seen only in older South Asian patients. The association between diabetes and mortality was strongest in younger patients, compared with older. The diabetes effect was as strong in white patients, but the

prevalence of diabetes higher in the South Asian group.

As reported in our earlier analysis, extreme elderly age and the presence of comorbidities were associated

with a lower likelihood of critical care admission, suggesting advanced care planning decisions on the ward.4

While this may have disproportionately affected patients in the White group who were significantly older

with more cardiac and respiratory disease, the increased likelihood of critical care admission and IMV in

Ethnic Minorities persisted after adjustment. This may reflect an increased severity of disease in multiple

Ethnic Minority populations, but falling short of significantly increased mortality in many.

Our finding of significantly increased mortality in the South Asian group is in agreement with reports which

found that people from Asian and Black ethnic groups were at increased risk of in-hospital death from

COVID-19, and that this was only partially attributable to pre-existing clinical risk factors or deprivation.8,18,35

We add an important and detailed picture of differences in characteristics of ethnic groups in hospital. The

prevalence of diabetes is also striking at around 40% in South Asian and Black patients and the mediation of

the mortality effect by diabetes is important. This appeared independent of chronic cardiac disease and

chronic kidney disease and is likely to be due to the multitude of other negative health associations carried

by the condition.

What of the increased mortality in South Asian patients left unexplained? Our models did not account well

for wide socioeconomic determinants of outcome, as well as nuance in the comorbidity data. Socioeconomic

inequalities contribute to differential exposure to infection, differential vulnerability following infection, and

differential consequences of infection as well as control measures.36 In other studies, at Local Authority

district level, the districts with a greater proportion of residents from non-White groups experienced higher

COVID19 mortality rates, as did districts with a greater proportion of residents experiencing deprivation

from low income.19 We did not find that deprivation at the level of the hospital was a significant predictor of

time to hospital admission or severity of illness in hospital, however, aggregation of deprivation at hospital

level masks individual socioeconomic effects. Future studies should examine the disaggregated effects

where possible.

Why was excess mortality not apparent among our Black population, as others have reported?8 It seems

unlikely this group are dying disproportionately in community compared with hospital settings, so any true

effect should be visible in our cohort. Given that our study includes 40% of the UK hospitalised population,

selection bias is clearly a possibility. On the other hand, it is possible that the estimates in our study are

correct, given that some population-level reports rely on older census data as the denominator. Our ongoing

work includes linking our dataset widely to better understand the place of the in-hospital stay as part

of the full patient journey.