Post by Admin on May 12, 2021 22:50:54 GMT

Fig. 2

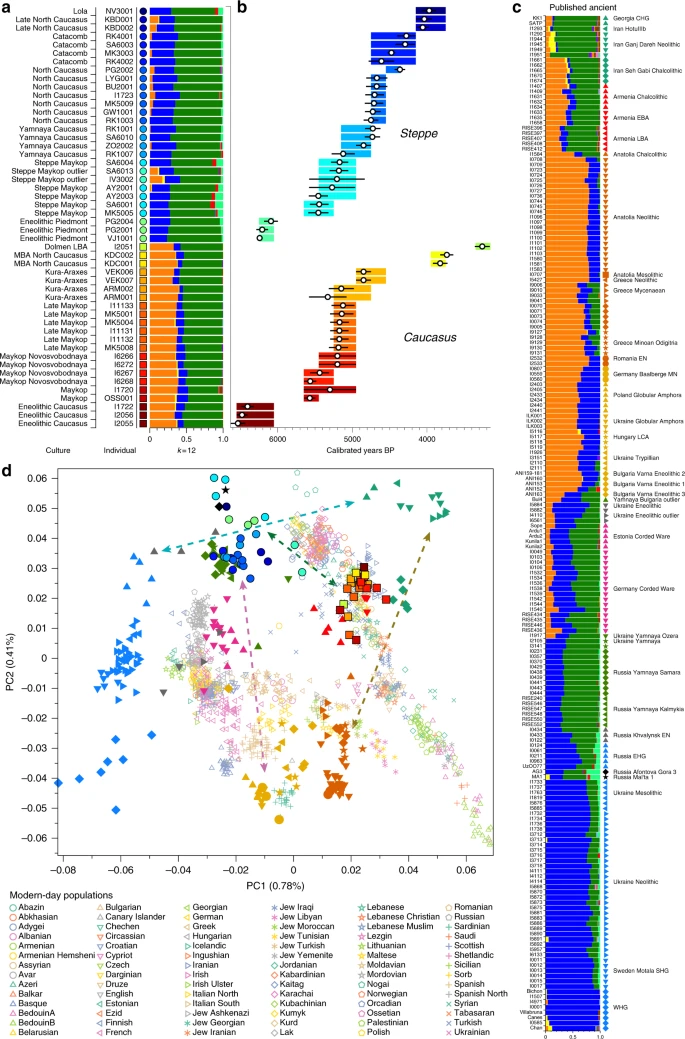

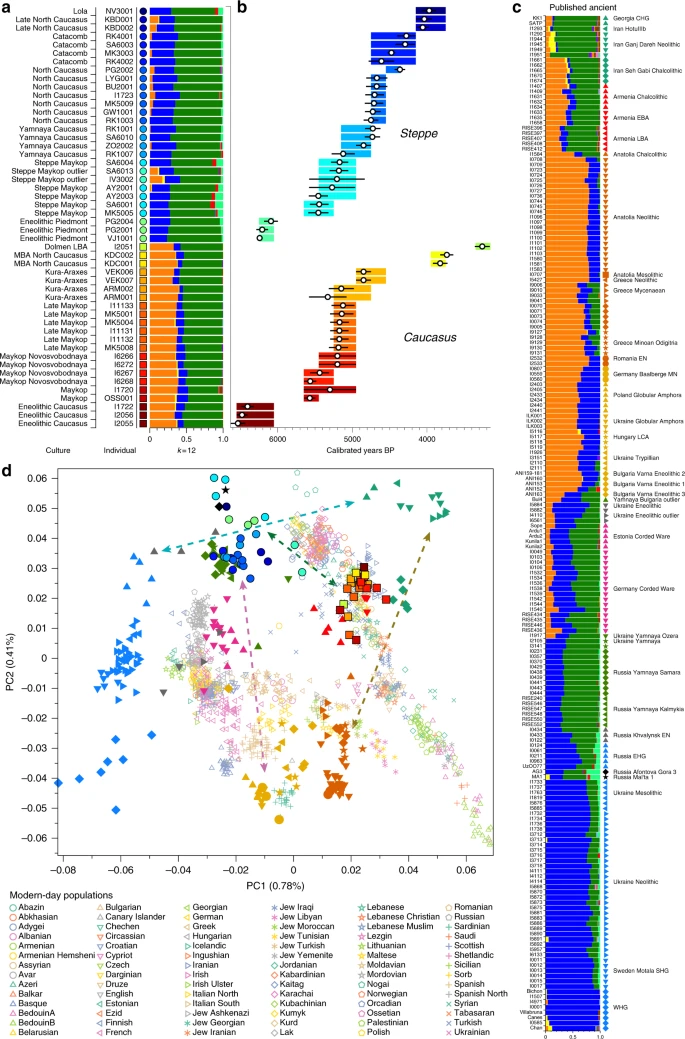

ADMIXTURE and PCA results, and chronological order of ancient Caucasus individuals. a ADMIXTURE results (k = 12) of the newly genotyped individuals (filled symbols with black outlines) sorted by genetic clusters (Steppe and Caucasus) and in chronological order (coloured bars indicate the relative archaeological dates, b white circles the mean calibrated radiocarbon date and the errors bars the 2-sigma range. c ADMIXTURE results of relevant prehistoric individuals mentioned in the text (filled symbols), and d shows these projected onto a PCA of 84 modern-day West Eurasian populations (open symbols). Dashed arrows indicate trajectories of admixture: EHG—CHG (petrol), Yamnaya—Central European MN (pink), Steppe—Caucasus (green), and Iran Neolithic—Anatolian Neolithic (brown)

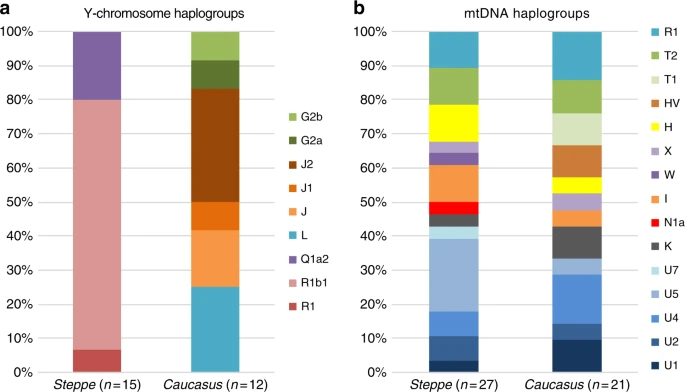

To understand and characterize the genetic variation of Caucasian populations, present-day groups from various geographic, cultural/ethnic and linguistic backgrounds have been analyzed previously24,25,26. Yunusbayev and colleagues described the Caucasus region as an asymmetric semipermeable barrier based on a higher genetic affinity of southern Caucasus groups to Anatolian and near Eastern populations and a genetic discontinuity between these and populations of the North Caucasus and the adjacent Eurasian steppes. While autosomal and mitochondrial DNA data appear relatively homogeneous across the entire Caucasus, the Y-chromosome diversity reveals a deeper genetic structure attesting to several male founder effects, with striking correspondence to geography, ethnic and linguistic groups, and historical events24,25.

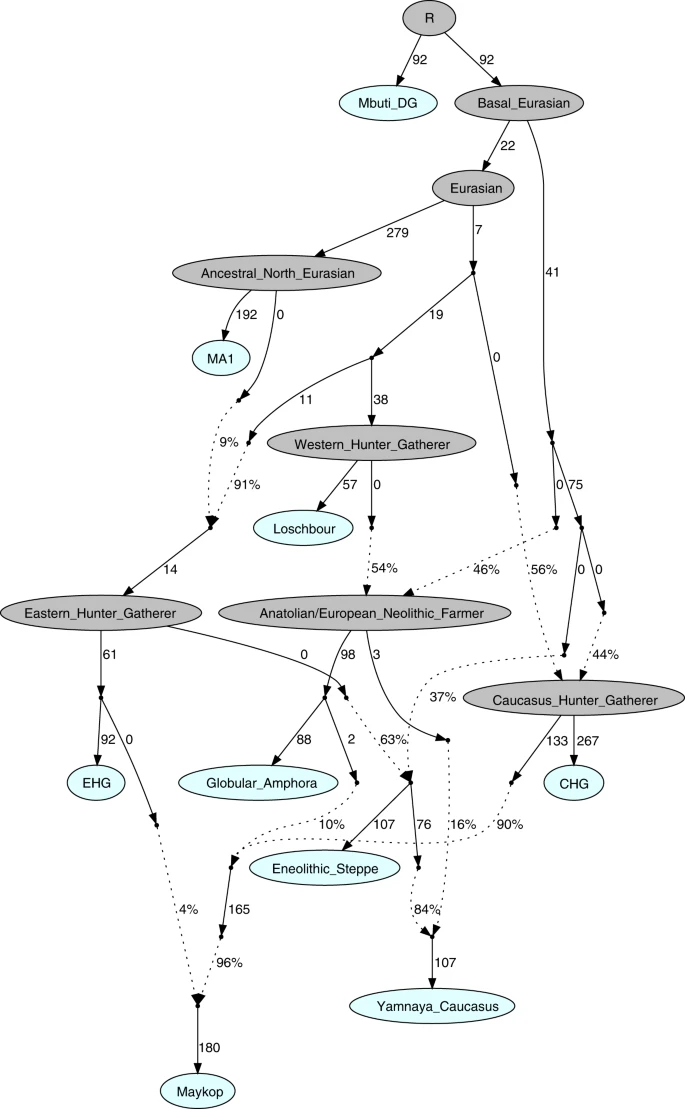

In our study, we aimed to investigate when and how the genetic patterns observed today were formed and test whether they have been present since prehistoric times by generating time-stamped human genome-wide data. We were also interested in characterizing the role of the Caucasus as a conduit for gene-flow in the past and in shaping the cultural and genetic makeup of the wider region (Supplementary Note 1). This has important implications for understanding the means by which Europe, the Eurasian steppe zone, and the earliest urban centres in the Near East were connected6. We aimed to genetically characterise individuals from cultural complexes such as the Maykop and Kura-Araxes and assessing the amount of gene flow in the Caucasus during times when the exploitation of resources of the steppe environment intensified, since this was potentially triggered by the cultural and technological innovations of the Late Chalcolithic and EBA around 4000–3000 BCE5 (Supplementary Note 2). Finally, since the spread of steppe ancestry into central Europe and the eastern steppes during the early 3rd millennium BCE was a striking migratory event in human prehistory18,19, we also retraced the formation of the steppe ancestry profile and tested for influences from neighbouring farming groups to the west or early urbanization centres further south.

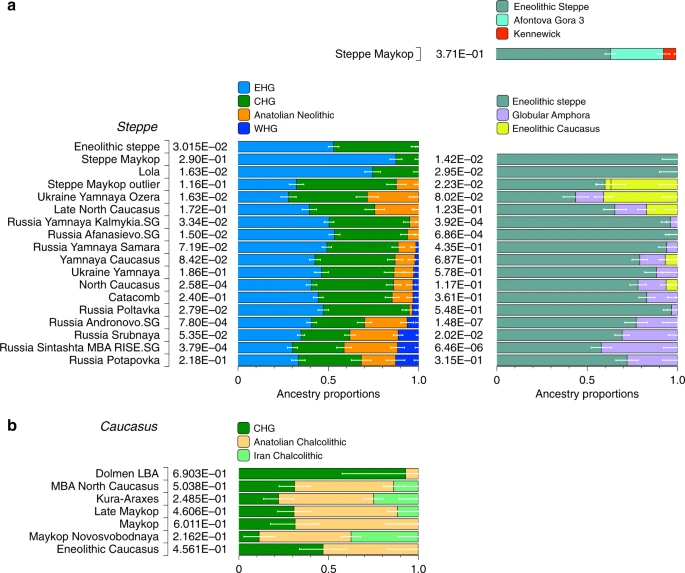

Here we show that individuals from our Caucasian time transect form two distinct genetic clusters that were stable over 3000 years and correspond with eco-geographic zones of the steppe and mountain regions. This finding is different from the situation today, where the Caucasus mountains separate northern from southern Caucasus populations. However, during the early BA we also observe subtle gene flow from the Caucasus as well as the eastern European farming groups into the steppe region, which predates the massive expansion of the steppe pastoralists that followed in the 3rd millennium BCE18,19.

ADMIXTURE and PCA results, and chronological order of ancient Caucasus individuals. a ADMIXTURE results (k = 12) of the newly genotyped individuals (filled symbols with black outlines) sorted by genetic clusters (Steppe and Caucasus) and in chronological order (coloured bars indicate the relative archaeological dates, b white circles the mean calibrated radiocarbon date and the errors bars the 2-sigma range. c ADMIXTURE results of relevant prehistoric individuals mentioned in the text (filled symbols), and d shows these projected onto a PCA of 84 modern-day West Eurasian populations (open symbols). Dashed arrows indicate trajectories of admixture: EHG—CHG (petrol), Yamnaya—Central European MN (pink), Steppe—Caucasus (green), and Iran Neolithic—Anatolian Neolithic (brown)

To understand and characterize the genetic variation of Caucasian populations, present-day groups from various geographic, cultural/ethnic and linguistic backgrounds have been analyzed previously24,25,26. Yunusbayev and colleagues described the Caucasus region as an asymmetric semipermeable barrier based on a higher genetic affinity of southern Caucasus groups to Anatolian and near Eastern populations and a genetic discontinuity between these and populations of the North Caucasus and the adjacent Eurasian steppes. While autosomal and mitochondrial DNA data appear relatively homogeneous across the entire Caucasus, the Y-chromosome diversity reveals a deeper genetic structure attesting to several male founder effects, with striking correspondence to geography, ethnic and linguistic groups, and historical events24,25.

In our study, we aimed to investigate when and how the genetic patterns observed today were formed and test whether they have been present since prehistoric times by generating time-stamped human genome-wide data. We were also interested in characterizing the role of the Caucasus as a conduit for gene-flow in the past and in shaping the cultural and genetic makeup of the wider region (Supplementary Note 1). This has important implications for understanding the means by which Europe, the Eurasian steppe zone, and the earliest urban centres in the Near East were connected6. We aimed to genetically characterise individuals from cultural complexes such as the Maykop and Kura-Araxes and assessing the amount of gene flow in the Caucasus during times when the exploitation of resources of the steppe environment intensified, since this was potentially triggered by the cultural and technological innovations of the Late Chalcolithic and EBA around 4000–3000 BCE5 (Supplementary Note 2). Finally, since the spread of steppe ancestry into central Europe and the eastern steppes during the early 3rd millennium BCE was a striking migratory event in human prehistory18,19, we also retraced the formation of the steppe ancestry profile and tested for influences from neighbouring farming groups to the west or early urbanization centres further south.

Here we show that individuals from our Caucasian time transect form two distinct genetic clusters that were stable over 3000 years and correspond with eco-geographic zones of the steppe and mountain regions. This finding is different from the situation today, where the Caucasus mountains separate northern from southern Caucasus populations. However, during the early BA we also observe subtle gene flow from the Caucasus as well as the eastern European farming groups into the steppe region, which predates the massive expansion of the steppe pastoralists that followed in the 3rd millennium BCE18,19.