|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 8, 2015 13:50:31 GMT

The anniversary of the funeral on 30 January 1965, which brought the capital to a standstill and took place a week after his death aged 90 on 24 January, is being marked by scores of events, including a service and wreath laying at the Houses of Parliament, a memorial service at Westminster Abbey, and the rebroadcast by BBC Parliament of the original live coverage.  In a tribute to his most famous predecessor, the prime minister, David Cameron, said: “Half a century after his death, Winston Churchill’s legacy continues to inspire not only the nation whose liberty he saved, but the entire world. His words and his actions reverberate through our national life today.” Churchill was above all a patriot with lessons to teach the world today, the prime minister said, as he laid a wreath at the feet of the statue in the House of Commons lobby. “He knew that Britain was not just a place on the map but a force in the world, with a destiny to shape events and a duty to stand up for freedom. That is why in 1940 – after France had fallen, before America or Russia had entered the war – he said this: ‘Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be free - and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.’ “Churchill was confident that freedom and democracy would win out over barbarism and tyranny in the end... and it did.” He added: “with every affront to freedom in this century, we must remember that courage and resolve in the last century.”  Deputy prime minister Nick Clegg wrote: “In memory of a man who defended our nation, defeated fascism, led the free world and has made generations of his fellow citizens proud to be British,” and Labour leader Ed Miliband’s message read: “With gratitude, respect and admiration for the leadership you showed during Britain’s darkest hour. Our country will always remember the hope you gave and the courage you inspired.” Cameron said ruefully that in one respect at least he would not be following the example of his hero: “The bottles of Pol Roger in Number 10, the practice of taking his cabinet out for lunch at the Savoy Grill. Sadly for my cabinet, that is not quite the current regime.” Churchill’s granddaughter, the author Emma Soames, said the family was touched that he is still so vividly remembered: “To me growing up he was a grandfather, but I came to realise at his death that he was so much more than that. The family are absolutely delighted that his life is being celebrated and his legacy expanded.” In the small hours of 30 January 1965 the great medieval Westminster Hall was finally cleared of the last of an estimated million people, who came to pay their respects as his body lay in state for three days: a brass plaque on the floor marks the spot where his coffin stood. By then the route to St Paul’s was already lined 10-deep with people, many having camped out overnight to secure the best places.  The vessel bears a commemorative plaque, given by the International Churchill Society, inscribed with the words of Richard Dimbleby’s commentary: “And so Havengore sails into history ... not even the Golden Hind had borne so great a man”. Havengore was built on the Thames in 1954, commissioned by the Port of London Authority as a survey vessel, but her elegant lines meant she was used as a flagship on many ceremonial occasions. By the time she was retired and sold in 1995, she was the authority’s longest serving vessel. Lavishly restored in private ownership, she has since joined in many public events including the river pagaents for the Queen’s Diamon Jubilee, and the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 9, 2015 14:27:51 GMT

Gilbert took on the role of official historian of Churchill in 1968 after Churchill’s son Randolph died. Randolph began the official biography of his father, leading a team of researchers, which included Gilbert beginning in 1962. Randolph and his team wrote two volumes of the biography, and they were disjointed and not very well written. I once asked Gilbert why Randolph’s volumes were so lacking, and he said that Randolph had great ideas but wasn’t disciplined in his execution. Gilbert was, to say the least, more disciplined, and he executed Randolph’s plan very well.  Gilbert took over the effort and completed the final six volumes of the biography, completely transforming the work and greatly elevating the quality. These six books chronicled Churchill’s life in great, well-written detail, offering extensive information in a flowing narrative. This was no mean feat given Churchill’s long and epic life, during which he was involved in virtually every major British domestic and international issue, about which there are thousands of documents and books. The full biography was so thorough and rich in detail that it has served as the jumping-off point for virtually every serious scholarly study of Churchill.  Gilbert condensed the 8-volume biography into a 1,000-page one-volume work, and he continued and expanded upon Randolph’s idea of editing companion volumes of documents that supported the biography, with extremely informative footnotes. The companion volumes are a treasure trove for historians (and it costs a bit of treasure to purchase them). He authored derivative works, such as Churchill and America and Churchill and the Jews, but it was his comprehensive biography and edited volumes of supporting selected documents that are his greatest legacies. Gilbert’s detractors, and they are mostly British, considered him a hagiographer. Of course, his job as official biographer was to unearth facts and present them in a sympathetic light in an appealing narrative, and he accomplished that exceptionally well. He also was criticized for simply presenting and not analyzing his material, and indeed he was more reliable chronicler than a probing scholar. But it was a chronicle for the ages. A caring Jew and ardent Zionist, Gilbert was active in the Soviet Jewry movement during the Cold War, and wrote books about the Holocaust and Jewish and Zionist history. He also produced some excellent atlases on Israeli history and the Israel-Arab conflict. When I first met him about two decades ago, it was in Jerusalem. I recall walking down a street with him once and he was excited to see a plaque on a building he hadn’t noticed before. He loved detail, and Israel. In my limited contact with Gilbert I sensed that it wasn’t always easy for him to be a Jew in his position. On the one hand, it was in a sense appropriate, since Jews in Britain and elsewhere were among Churchill’s most consistent supporters and admirers. Churchill was philo-Semitic and grew to become a leading Zionist, which caused him friction with Conservatives and Socialists alike. I recall Gilbert telling me that Randolph Churchill was also philo-Semitic. If memory serves, Gilbert said that Randolph had a penchant for hiring Jews as his researchers, and that he once hired an Indian, figuring he’d hire someone not Jewish for a change, but it turned out that man was Jewish as well! Still, in the half-century that Gilbert worked many in Britain weren’t sympathetic to Jews or Israel, and some were outright hostile to each, and I gathered that Gilbert felt his Jewishness wasn’t always well received. Clearly, Gilbert’s legacy will far outlive his life. We are above all indebted to him for his excellent research and writing about Churchill, making accessible to anyone who cares to read detailed knowledge about the life and achievements of this monumental statesman, which is in itself a significant contribution to history and Western civilization. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Feb 14, 2015 15:25:32 GMT

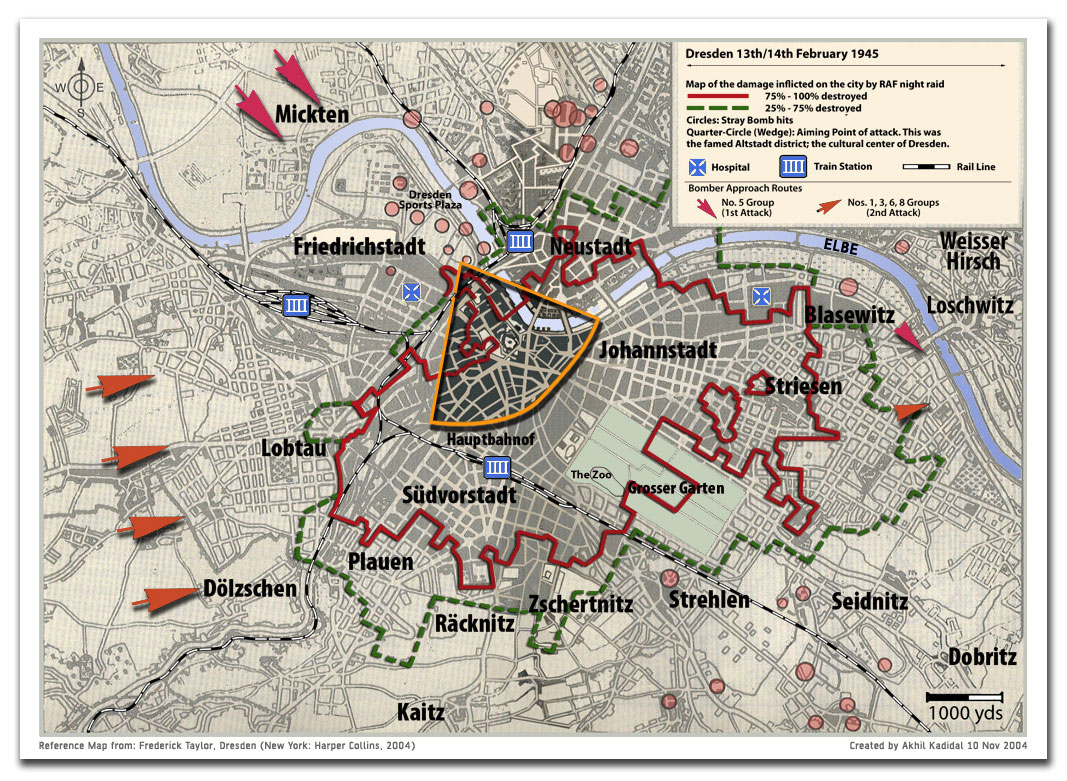

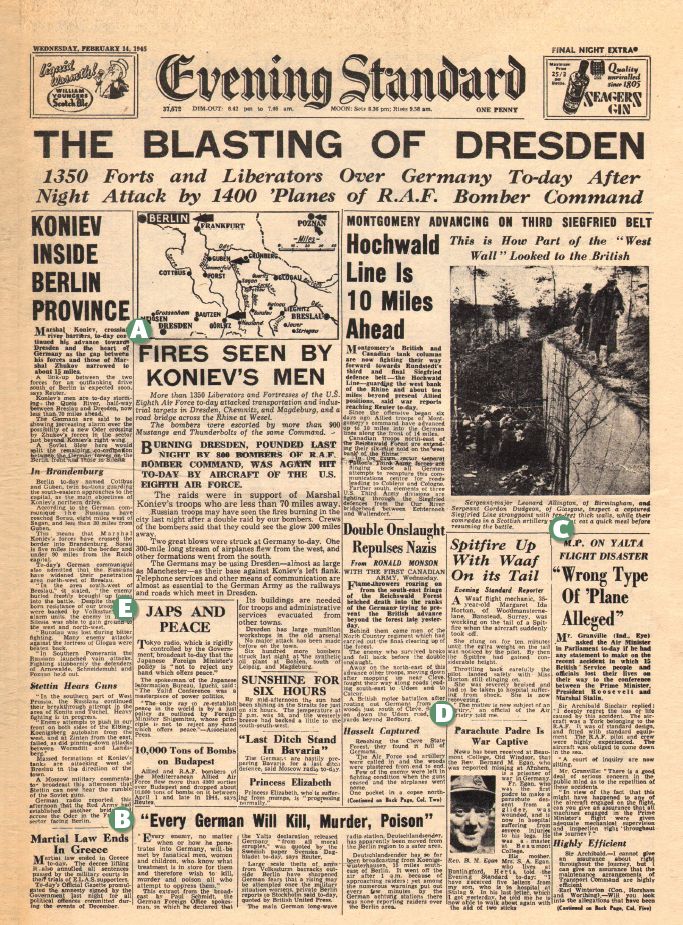

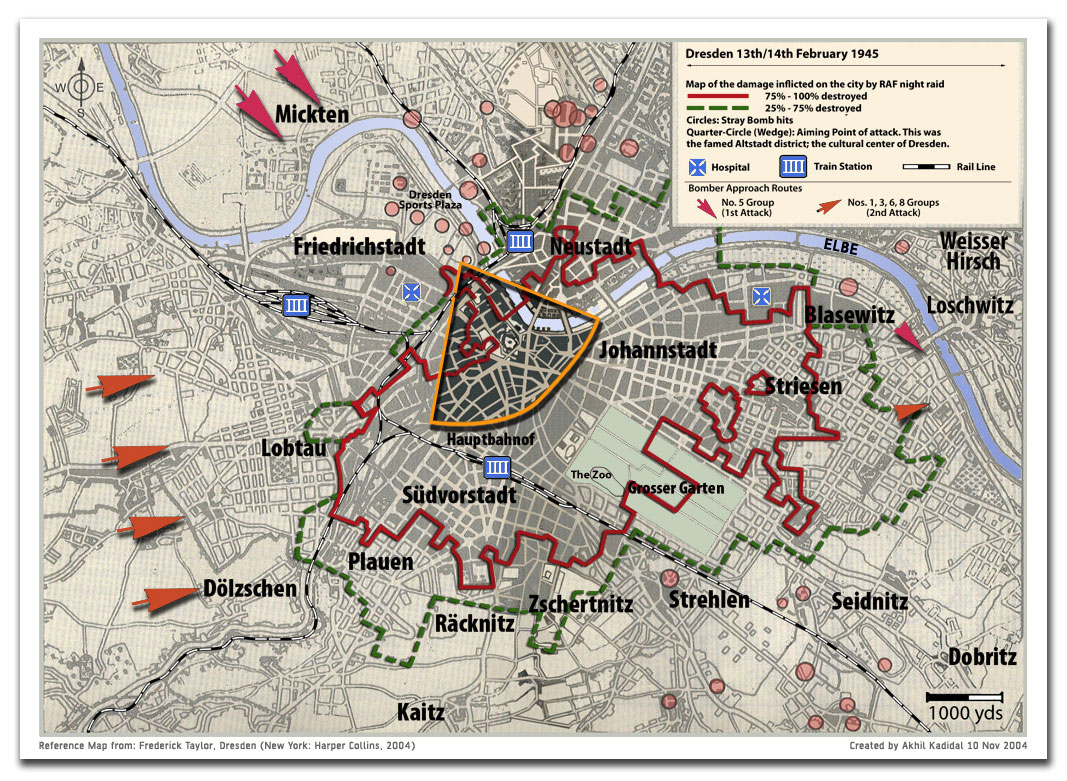

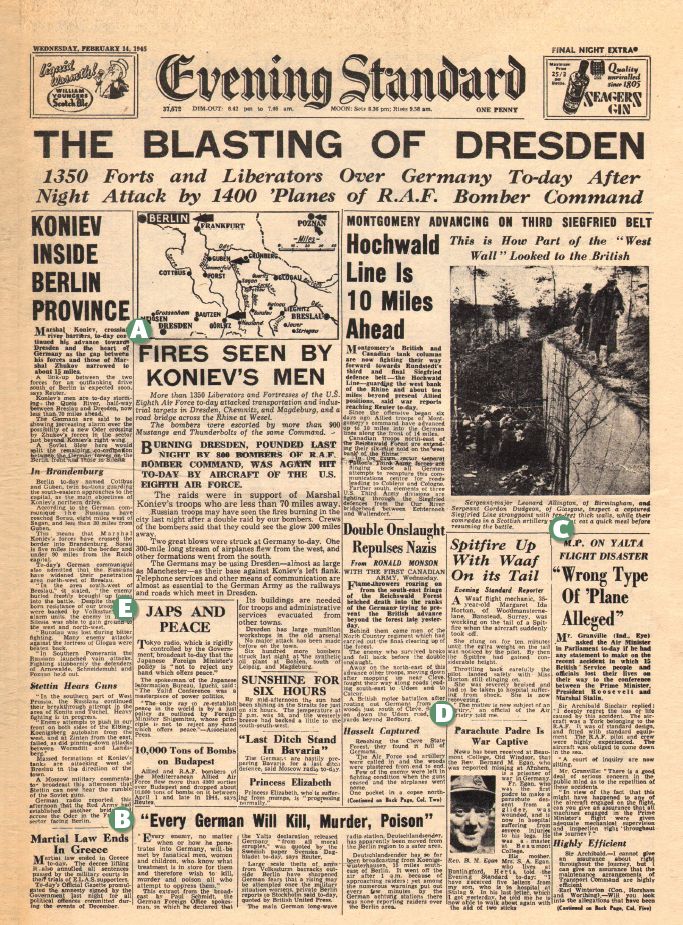

A few weeks before the end of World War Two, Winston Churchill drafted a memorandum to the British Chiefs of Staff: 'It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed ... The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing.' More than half a century later, the strategic bombing campaign continues to nag the national conscience. Some historians go as far as to suggest that by bombing cities the British 'descended to the enemy's level' (John Keegan). This is, of course, an exaggeration. The bombing of Dresden cannot be equalled with the horrors of Auschwitz. Many felt that the Germans deserved to reap the whirlwind they had sown. Yet Bomber Command's policy of targeting residential areas clearly contradicted Chamberlain's pre-war statement in parliament that it was 'against international law to bomb civilians as such and to make deliberate attacks on the civilian population'. How could a nation so proud of its high moral standards drop bombs on women and children? This was the time when Churchill began to think about the need for an 'absolutely devastating exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland.' When on the night of 24 August 1940 the German air force - the Luftwaffe - accidentally and against Hitler's orders - dropped some bombs over London, the British prime minister requested a retaliatory raid on Berlin. Hitler responded by going ahead with the Blitz, and the following months and years saw tit-for-tat raids on each country's cities. At the same time, Britain's air force began to realise that its bombers were not able to find and hit specific war targets such as airfields or armament factories. An investigation revealed that just one in five aircraft was succeeding in dropping its bombs within five miles of its target. Under such circumstances, the bombing offensive could only be effective if it was directed at targets as big as cities.  Consequently, in February 1942, Bomber Command was instructed to shift the focus onto the 'morale of the enemy civil population'. This new policy came to be called 'area bombing'. The aiming points thereafter, for bombing raids, were no longer military or industrial installations, but a church or other significant spot in the centre of industrial towns. And since fire was found to be the most effective means of destroying a town, the bombers now carried mainly incendiary bombs. Thus, the exigencies of war had rendered the traditional distinction between combatants and non-combatants meaningless. Nearly everybody living in an 'industrial town' was considered to contribute directly or indirectly to the German war effort, and had therefore become a supposedly legitimate target. Moreover, Churchill thought that the bombing of communication centres in eastern Germany might aid the Soviet advance on Berlin. Bomber Command was ordered to attack Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig and other east German cities to 'cause confusion in the evacuation from the east' and 'hamper the movements of troops from the west'. This directive led to the raid on Dresden and marked the erosion of one last moral restriction in the bombing war: the term 'evacuation from the east' did not refer to retreating troops but to the civilian refugees fleeing from the advancing Russians. Although these refugees clearly did not contribute to the German war effort, they were considered legitimate targets simply because the chaos caused by attacks on them might obstruct German troop reinforcements to the Eastern Front. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Apr 2, 2015 13:54:51 GMT

It was while Churchill was in India that he discovered an intense desire to learn history. He “resolved to read history, philosophy, economics, and things like that.” He wrote to his mother Jennie, asking her to send books – mostly history books. He “devoured” Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and Macaulay’s 12-volume History of England. He also read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, Darwin, Malthus, Aristotle, Plato and others. Using his mother’s considerable influence, Churchill arranged to work as a war correspondent for the Pioneer newspaper and the Daily Telegraph. He traveled from Bangalore to Nowshera to join the Malakand Field Force at the front, where it was commanded by General Sir Bindon Blood. “For three years,” Churchill wrote in My Early Life, “the British held the summit of the Malakand Pass and thus had maintained the road from the Swat Valley and across the Swat River by many other valleys to Chitral.” The Malakand Pass was, according to historian Arthur Herman, “a deep cleft in a jagged bowl of mountainous ridges, guarded by a typical British garrison of Sikhs, Punjabis, and Bengal Lancers under the command of white officers.” Muslim Pathan tribes in the Swat Valley had attacked the soldiers holding the Malakand Pass and laid siege to Chakdara, the fort that defended the bridge across the Swat River. This was a direct challenge to British imperial rule. Churchill wrote to his brother Jack on August 31, 1897, that “The frontier is a scene of great trouble and excitement. Practically all the fierce wild warlike tribes of Afghan stock . . . are in revolt.” He believed that “the time of offensive measures is now at hand. It is impossible,” he wrote, “for the British Government to be content with repelling an injury – it must be avenged. Churchill was clearly excited about the impending battle and his participation in it. He wrote to his mother on September 5, 1897, that “At the first opportunity I am to be put on the strength of this force – which will give me a medal if I come through.” He continued, “As to the fighting, we march tomorrow, and before the week is out, there will be a battle – probably the biggest yet fought on the frontier this year.” He brashly yet prophetically told his mother that he had “faith in my star – that is that I am intended to do something in the world.”  Churchill was frequently at the front and under enemy fire. On one occasion, after other officers fell in battle, he commanded a company of Punjab infantry. According to William Manchester, “[t]here can be no doubt that he was remarkably brave, at times even rash.” In a letter he told his mother that he rode on his pony along a skirmish line while other soldiers sought cover on the ground. His commanding officers lauded his courage and bravery. “The war in the mountains of the North-West Frontier,” wrote Churchill biographer Carlo D’Este, “was fierce and without quarter.” In one letter, Churchill described the fighting. “The tribesman,” he wrote, “torture the wounded & mutilate the dead. The troops never spare a man who falls into their hands – whether he be wounded or not . . . The picture is a terrible one.” In one instance of reprisals, Churchill wrote, “we proceeded systematically, village by village, and we destroyed the houses, filled up the wells, blew down the towers, cut down the shady trees, burned the crops and broke the reservoirs in punitive devastation.” In one of his dispatches that appeared in the Daily Telegraph on November 6, 1897, Churchill eloquently explained the situation faced by Britain on the North-West Frontier: The rising of 1897 is the most successful attempt hitherto made to combine the frontier tribes. It will not be the last.. . . The simultaneous revolt of distant tribes is an evidence of secret workings. . . Civilization is face to face with militant Mohammedanism. When we reflect on the moral and material forces arrayed, there need be no fear of the ultimate issue, but the longer the policy of half-measures is adhered to the more distant the end of the struggle will be. An interference more galling than complete control, a timidity more rash than reckless, a clemency more cruel than the utmost severity, mark our present dealings with the frontier tribes. To terminate this sorry state of affairs it is necessary to carry a recognized and admitted policy to its logical and inevitable conclusion; to obtain the Gilgit-Chitral-Jellalabad-Kandahar frontier, and reduce to law and order everything South of that line. Churchill returned to Bangalore and garrison duty, and used the time to write his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, which was published in 1898. Churchill began this book with a vivid description of the geography of the battlefield. “The Malakand,” he wrote, “is like a great cup, of which the rim is broken into numerous clefts, and jagged points.” The Malakand Pass was the deepest cleft. Guarding the pass was a fort, Chakdara, which overlooked a “broad graded road [that] runs like a ribbon across the plain.” The road crosses a mountain pass then “leads to the fortified bridge across the [Swat] river.” “Without this road,” Churchill explained, “there would have been no Malakand Camps, no fighting, no Malakand Field Force, no story. It is the road to Chitral.” British governments, with the exception of Lord Rosebery’s, had since 1876, he wrote, followed a “forward policy” on the North-West Frontier, and that meant holding Chitral.  He described the conflict as “the great tribal upheaval of 1897,” and attributed its cause to a Mohammedan jihad against the infidel. “The mine was fired,” he wrote. “The flame ran along the ground. The explosion burst forth in all directions.” In late July 1897, the Malakand Camp was repeatedly assaulted by the enemy along the two roads that accessed the camp. After heavy fighting and considerable losses on both sides, the tribesmen realized that the Malakand Camp could not be taken. “Thus,” wrote Churchill, “the long and persistent attack on the British frontier station of Malakand, languished and ceased.” The enemy now laid siege to Chakdara fort. Churchill noted that India’s Governor-General in Council determined to come to the relief of the besieged fort and ordered General Sir Bindon Blood to form the Malakand Field Force for that purpose. Blood’s troops reached the Malakand on August 1st, and the next day went into action and successfully relieved the siege of the fort. Then, Churchill wrote, “[t]he 11th Bengal Lancers, forming a line across the plain, began a merciless pursuit up the valley.” “No quarter was asked or given,” Churchill noted, “and every tribesman caught was speared or cut down at once.” Commenting on the scene of carnage, Churchill memorably wrote: “The spectator who may gaze unmoved on the bloodshed of the battle, must avert his eyes from the horrors of the pursuit, unless, indeed, joining in it himself, he flings all scruples to the winds, and indulges to the full those deep-seated instincts of savagery, over which civilization has but cast a veil of doubtful thickness. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Apr 11, 2015 14:47:53 GMT

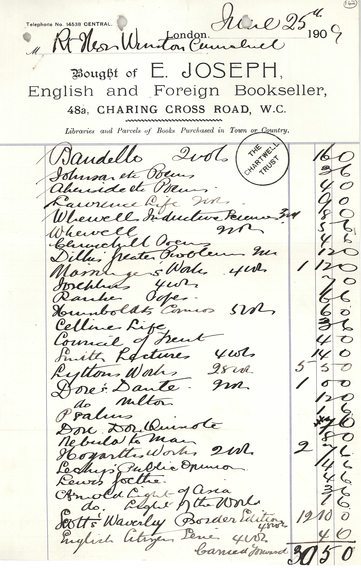

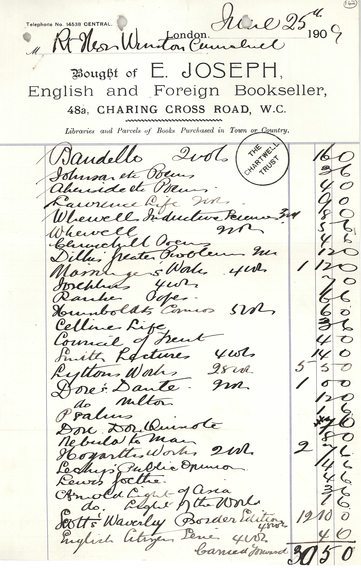

Tomorrow is the 32nd Birthday of Chartwell Booksellers, my small, independent bookstore in midtown Manhattan devoted to the writings of Winston Churchill. For thirty-two years, people (well, a few) have been asking me: 'Why a Churchill bookshop in New York City? Shouldn't you be in London?' And, for thirty-two years, I have been answering: 'No. Churchill is actually more popular here.'  He was half American; half-New Yorker, in fact. Churchill's mother, Jennie, was born in Brooklyn, the daughter of a New York financier, Leonard Jerome, who built and lost several large fortunes here, and for a time was the principal owner of The New York Times. Winston Churchill was always extremely proud of the impure American strain in his otherwise aristocratic British lineage (as descended from the first Duke of Marlborough). It lent him, he was certain, a dimension of independence.  Churchill's long political career, filled with missteps, restarts and renewals is, for better and worse, more widely recollected in England. Our view of him in the U.S. is more narrowly adoring: He saved western civilization with his stewardship during World War II and did so as a strikingly memorable character, with his cigars, his siren suits, his singular speeches and his glowering gaze. It seems safe to say that the British view of Churchill is more colored -- I would say unfairly -- by perceived catastrophes throughout his (perceived) checkered career. These, in fact, were often ruthlessly manufactured or exaggerated by powerful enemies within his own Conservative party, and within the Labor party; a party that Churchill viewed as a tool of Communism during its early existence and fought fiercely.  Winston Churchill loved bookstores. I can't say how George W. feels about them. The Churchill Archives at Churchill College, Cambridge, possesses virtually every invoice relating to Churchill's book purchases over more than fifty years. They are voluminous. On December 4, 1900, twenty-six-year-old Winston Churchill paid his first bookstore bill -- going back to December 1897, in the amount of seventeen pounds-seventeen shillings-and-sixpence -- to his father's favorite bookseller, the esteemed James Bain. He also made a series of new purchases at this time, including copies of Rawlinson's History of Herodotus, Morley's Walpole, and Newman's Apologia. His acquisitions from Bain over the next two years would include two sets of his father's speeches and a copy of H. G. Wells's The Time Machine. It would appear that Churchill's final peacetime book purchase before the onset of World War II was from (the blessedly still extant today) Hatchards of Picadilly, in February 1939: two copies of The Bible as Literature, a fascinating choice when one considers the impending influence of the bible as literature in the syntax of Churchill's great speeches of the war.  One could compose a marvelous history of London bookselling merely by reconstructing the history of all those shops that Churchill frequented. I would love to do this myself one day. But I feel I have more pressing business just now. Winston Churchill built a substantial library over the course of his life, a library that his son Randolph dispersed quickly once Churchill's life had ended. (The bookplate pictured at the top of this story was created by Randolph, according to Sir Martin Gilbert, and slapped into every one of Churchill's books after he was gone.)  No inventory of Churchill's library exists, to my knowledge. Using the invoices preserved in the Churchill Archives, I am hoping to reconstruct the full contents of that library -- on paper, at first. If anyone out there would then like the actual books -- an all-out reconstitution of Winston Churchill's library, book by book -- well, please do get in touch with me. I am around most weekdays, 10-6, at Chartwell Booksellers. |

|