|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 14, 2021 4:01:48 GMT

Analyses of sequence data confirm higher levels of Denisovan ancestry in Ayta Magbukon Negritos than in Papuans We explored further our finding of high levels of Denisovan ancestry in some Philippine Negritos; generated, at high coverage (mean depth of ∼37×), whole-genome sequences of five Ayta Magbukon Negritos; and merged these data with the publicly available genome sequence datasets of archaic and modern humans (see STAR Methods).1, 2, 3,23 Following comparative analyses of high-coverage genomes of Australasians, we confirm that the Ayta Magbukon possess the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world (Figures 4A–4C, S6A, and S6B; Data S2A–S2C; see STAR Methods), levels that are 34%–40% higher than that of Australians or Papuans (based on the difference in Denisovan ancestry estimates using f4-ratio statistics; Figure 4B).  Figure 4 Analyses of high-coverage genomes confirm higher levels of Denisovan ancestry in Ayta Magbukon relative to Australopapuans We used the S’ framework15 to identify (high confidence) archaic regions in the genomes of Ayta Magbukon and Papuans (see STAR Methods) and to exclude the potential biases in f4-ratio statistics for estimating the levels of archaic ancestry in populations.26 The average amount of Denisovan sequence per individual in Ayta Magbukon is significantly higher than that of Papuans (51.94 Mb [95% CI: 44.62.66–59.25 Mb] versus 41.96 Mb [95% CI: 39.54–44.37 Mb]; p = 3.7 × 10−3), showing that Ayta Magbukon have at least ∼24% more Denisovan ancestry than in Papuans (Figures 4D and S6C). Moreover, both Ayta Magbukon and Papuans exhibit Denisovan segments that have moderate affinity to the reference Altai Denisovan, a match rate of ∼50% (Figures 5A and 5B). This suggests that the archaic groups introgressing into the Ayta Magbukon and Papuans are likely to be distantly related to the Altai Denisovan of Siberia, consistent with previous observations.15,16  Figure 5 Contour density plots showing the affiliation of S’-detected introgressed segments to the reference archaic genomes The high levels of Denisovan ancestry in Ayta may be due to a recent Denisovan admixture event into this population. This would make the admixture tracts longer and easier to detect, which may conceivably account for the 24% excess Denisovan ancestry relative to Papuans. However, we find that this is not the case, given that the mean tract lengths are similar for the Ayta and Papuans (260 Kb [95% CI: 239–282 Kb] versus 262 Kb [95% CI: 254–271 Kb]; Mann-Whitney test; p = 0.6). Likewise, we do not find a significant difference in the cumulative distributions of Denisovan tracts in Ayta Magbukon and Papuans (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; p = 0.70). Our findings imply that the admixture is of similar age in the two populations, which lends credence to our claim that there is more Denisovan admixture in the Ayta than in Papuans. Tract lengths of Denisovan ancestry have previously been investigated in Papuans and in some Philippine Negrito groups with varying results. Browning et al.15 found no difference in Denisovan tract lengths attributed to the suggested two introgression events into East Asians and Papuans. Similarly, Jacobs et al.16 found no difference in mean Denisovan tract lengths in Papuans but reported a difference in the tract length distribution consistent with two different Denisovan introgressions into Papuans. Wall et al.18 found slightly longer mean tract lengths in an Aeta group (likely the Ayta Mag-antsi and Mag-indi in our dataset) than in Papuans, suggesting separate Denisovan introgression events into Aeta and Papuans. Note, however, that the mean tract lengths found by Wall et al.18 are ∼15 times shorter than those found by Jacobs et al.16 and, in our estimates, at least partly attributed to different inference approaches, making direct comparisons difficult. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 15, 2021 0:00:14 GMT

Independent Denisovan introgression event into Philippine Negritos The significantly higher level of Denisovan ancestry in Ayta Magbukon relative to Papuans highlights the possibility of an independent Denisovan introgression event in the Philippines among Negritos that is different from the Denisovan introgression event into the ancestors of Australopapuans. This observation is consistent with recent studies suggesting multiple pulses of Denisovan introgression into humans, that Denisovans were probably widespread throughout ISEA, and that Ayta Negritos were likely to have experienced a second Denisovan introgression event.12,15,16,18,27 Hence, we further examined the lines of evidence for an independent Denisovan introgression event into Negritos after the divergence between Negritos and Papuans. First, we find that Negritos possess a Denisovan ancestry that is not associated with the Australasian-related ancestry in Australopapuans (Figure 3A; see STAR Methods). Most Negritos form a clear outlier to the slope that correlates Denisovan ancestry and Australasian-related ancestry in Oceanians and Indonesians (Figure 3A). Second, the substantially higher Denisovan ancestry in Negritos (Figures 3B, 3C, 4A–4D, and S5A–S5O), relative to Papuans, is consistent with a model of an additional Denisovan introgression event into Negritos. Alternatively, it could be caused by a dilution of Denisovan ancestry in Papuans by admixture with populations containing little Denisovan ancestry. However, neither we (Figures S7A–S7L; see STAR Methods) nor previous studies24,28 find evidence for recent gene flow from East Asians or Europeans into highland Papuans. On the contrary, Negritos do display evidence for recent admixture with Cordilleran-related East Asians (who carry very little Denisovan ancestry; Figures 1D, S3A, and S3B). Third, an explicit population topology model using qpGraph, based on a shared Denisovan introgression event into Negritos, Australians, and Papuans, was rejected (Figure 6A; see STAR Methods). This is in contrast to the models fitting a separate Denisovan introgression event into Negritos (Figures 6B and 6C; all f-stats are within 1.18 standard error).  Figure 6 Admixture graph models of Denisovan introgression into Philippine Negritos and Papuans Simulations support two distinct Denisovan lineages introgressing independently into Ayta Negritos and Papuans We performed simulations using the coalescent simulator msprime29 (see STAR Methods) to evaluate whether a null model of shared Denisovan introgression event into the common ancestor of Ayta Negritos and Papuans (Figure 7F) or the alternative models (Alt1, Alt2, Alt3, and Alt4) of multiple Denisovan admixture events (Figures 7K, 7P, 7U, and 7Z) produce patterns of Denisovan ancestry that are consistent with the observed data (Figures 7A–7E), where Ayta Negritos possess higher levels of Denisovan ancestry than Papuans. Alt1 model (Figure 7K) depicts an additional admixture event into Ayta Negritos coming from a distinct and unsampled Denisovan population, after an admixture event in the shared ancestral population of Ayta Negritos and Papuans. Alt2, Alt3, and Alt4 models depict completely separate Denisovan introgression events into the ancestral populations of Ayta Negritos and Papuans happening at different time periods (Alt2 and Alt3; Figures 7P and 7U) or at similar times (Alt 4; Figure 7Z).  Figure 7 Evidence for independent Denisovan introgression event into Philippine Negritos In contrast to a null model of shared Denisovan admixture event, simulations based on a model with a separate Denisovan introgression event into Negritos (Alt1, Alt2, Alt3, and Alt4) produce patterns of Denisovan ancestry that are consistent with the observed data (Figure 7). All alternative models consistently replicate three pieces of empirical evidence: (1) higher level of Denisovan ancestry in Ayta Negritos than in Papuans; (2) higher ratio of Denisovan over Australasian ancestry in Ayta Negritos than in Papuans; and (3) Ayta Negritos falls outside the slope formed by Papuan-related groups when plotting the correlation between Denisovan ancestry and Australasian ancestry (Figure 7). Only Alt4 model, where the timing of the separate Denisovan introgression events into Ayta Negritos and Papuans occurred around the same time, produced similar levels of mean Denisovan tract length in Ayta Negritos and Papuans, a pattern consistent with the empirical data (Figures 7C and 7Ab). Consequently, only the Alt4 model produced qualitative patterns that are consistent with all of the empirical data. Altogether, our simulations provide support for the presence of two separate Denisovan lineages that independently introgressed into the ancestors of Ayta Negritos and Papuans, likely occurring around the same time after the Negrito-Papuan divergence 53 kya (95% CI: 41–64 kya). Upon entry of the first modern human migrants into Sunda and Sahul (ancestors of Negritos and Australopapuans), these ancestral Australasian groups likely experienced admixture with deeply divergent Denisovan-related populations scattered all throughout the ISEA and the Oceania region.15,16 Despite the fact that the populations with the highest levels of Denisovan ancestry are found in the regions of ISEA and Near Oceania, no Denisovan fossils have yet been discovered in the area. This may, in part, be limited by the lack of information on the definitive phenotypic characteristics of Denisovans. Most of the available knowledge on Denisovans is based on genomic data from the Altai Denisovans of Siberia.3,10 The only other direct evidence of Denisovans outside of Siberia is from the Baishiya Karst Cave site of the Tibetan Plateau,30,31 where an ancient proteome and an ancient mitochondrial DNA analysis revealed the Xiahe hominin to be phylogenetically affiliated with the Altai Denisovan. This led to the proposition that the other previously discovered archaic humans in the region may in fact be Denisovans, such as, among others, the Xujiayao and Penghu-1 individuals (Figure S1).30,32,33 Additionally, the physical evidence for a previously undescribed hominin in Luzon 67 kya, where present-day Negritos reside,34,35 combined with the genetic evidence presented here, raises the possibility that the suggested Homo luzonensis and Denisovans were likely genetically related, either as distinct forms or possibly belonging to the same group residing on the islands.36,37 Furthermore, it is not entirely impossible that the recently identified new species of archaic hominins in the Indonesian island of Flores, the Homo floresiensis,38 may also be related to Denisovans. Hence, the presence of multiple archaic human remains in the region, together with the genomic evidence presented here and elsewhere,15,16,31,37,39 raises the possibility that the Denisovans comprised deeply structured populations with considerable genetic and phenotypic diversity, enabling them to adapt into a wide variety of environments and thus inhabit a broad geographic range across the Asia-Pacific region.36,37,40,41 This is supported by the genomic data showing that Papuans experienced a distinct Denisovan introgression event as recent as ∼25–30 kya,16,37 which is several millennia after the divergence between Ayta Negritos and Papuans ∼53 kya. Though our interpretation provides a parsimonious explanation for the overlapping presence of archaic human remains and present-day populations with high levels of Denisovan ancestry in ISEA, this is not in line with the current palaeoanthropological analyses of the available fossil data. The definitive phylogenetic relationships between Denisovans, Homo luzonensis, Homo floresiensis, and other archaic hominins in the region still remain to be determined and will likely be resolved with the availability of ancient DNA or ancient proteomic data in the future. Conclusions While we await the discovery and successful extraction of ancient DNA from Denisovans in challenging tropical environments of the ISEA region, a computational genetic approach appears to be the only viable alternative at this stage.7,15,42 This approach was previously shown to be successful in advancing our understanding on how archaic hominins shaped our past and our biology.7,8,40,41 Moreover, as we take full advantage of the available computational tools, we underscore the importance of including underrepresented populations in genomic investigations, such as the Philippine Negritos. Our genomic analysis on Philippine Negritos shed light on an important section of human evolutionary history: the previously unappreciated complex interactions between modern humans and Denisovans in the ISEA region. Here, we have presented evidence for the possible presence of diverse Islander Denisovan populations, who differentially admixed with incoming Australasians across multiple locations and at various points in time. Consequently, this led to variable levels of Denisovan ancestry in the genomes of Philippine Negritos and Papuans. In ISEA, Philippine Negritos later admixed with East Asian migrants who possess little Denisovan ancestry, which subsequently diluted their archaic ancestry. Some groups though, such as the Ayta Magbukon, minimally admixed with the more recent incoming migrants. For this reason, the Ayta Magbukon retained most of their inherited archaic tracts and left them with the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world. Supplemental Information Philippine Ayta possess the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world www.cell.com/cms/10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.022/attachment/99379df4-bf6c-47ff-b900-46b9f673f310/mmc1.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 15, 2021 3:00:08 GMT

Ethnolinguistic Background of Philippine Negritos

All Philippine Negritos speak a language that is classified under the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) branch of the Austronesian language family. To date, there are ∼30 self-identified Negrito groups who speak a distinct MP language. Many of these languages are classified as severely endangered, while some, such as those of Iraya Agta, Dicamay Agta, and Villa Viciosa Agta, have already been declared extinct. In addition, the majority of these languages are classified as a first order branch within their respective subfamilies, indicating long periods of isolation among Negrito groups. This isolation likely brought about wide-ranging innovations into their languages, thereby distinguishing it from the other languages of neighboring non-Negritos.

In this study, we have included a total of 25 MP-speaking Negrito populations (Figure 1A), who following direct consultation with the respective cultural communities, are labeled in accordance with the group’s own preference to be called themselves. Most of the group names are based on the retention of a reflex of the proto-MP word ∗ʔa(R)ta, which refers to ‘Negrito person’19. The variations in their group names are alterations in the reflex of the medial consonant proto-MP ∗R, for instance the group names of Arta, Agta, Ayta, Alta, and Atta. Other group names are based on locations, such as Dupaningan and Dumagat, where both words retain the initial du as an old locative specifier. Dupaningan comes from the word dupaneng ‘other side or opposite side of the mountain’ and the locative nominalizing suffix -an. Dumagat is an endonym for the Negrito group that lives along the Umiray River, such as the Dumagat Agta of General Nakar in this study. The word Dumagat is derived from the locative specifier du ‘from’ and the place called magat ‘Magat River’, hence Dumagat would refer to the people ‘from Magat river’, indicating local historical migrations which may pertain to the origins of Dumagats from the Magat River basin.

The subsistence patterns of Philippine Negritos that we visited have increasingly shifted toward a mixed foraging and farming and/or urbanized lifestyle. Some engage in local trades and/or in seasonal contractual labor. Of all the Negrito groups we visited, only some individuals from the Agta Maddela and Agta Casiguran cultural communities retained a predominant hunting and gathering way of subsistence. This is consistent with previous observations, where in a span of four decades69, the combination of forest degradation, expansion of agricultural lands, increased accessibility brought about by rapidly expanding infrastructure development, and the inroads of modernized lifestyle have significantly affected the cultural practices of Negritos away from their traditional nomadic hunter-gathering mode of living.

Aside from the change in subsistence patterns, the religious practices of Philippine Negritos have also largely shifted in the advent of increasing development and urbanization, where Christian missionaries gradually extended their reach into the formerly inaccessible areas of Negrito cultural communities. Despite being Christianized, most Negritos still retain some traditional or animistic features in their belief system.

In this study, we grouped the Negrito populations based on their geographic location and the genetic clusters observed following PCA and Admixture analysis (see STAR Methods). The Philippine Negritos are classified into Northern Negritos of Luzon and Southern Negritos outside of Luzon. Additionally, Northern Negritos are classified into Northeast Luzon Negritos, Central Luzon Negritos, Southern Luzon Negritos, and Southeast Luzon Negritos.

Northeast Luzon Negritos

The Northeast Luzon Negritos include Negrito populations found in Cagayan, Isabela, and Quirino provinces of the Cagayan Valley region and the northeast section of Aurora province. The Northeast Luzon Negritos in this study are represented by the cultural communities of Agta Labin of Lal-lo, Cagayan; Agta Dupaningan of Palaui Island, Cagayan; Atta Rizal (also known as Agta Rizal or Atta Faire) of Rizal, Cagayan; Agta Casiguran of Casiguran, Aurora and Nagtipunan, Quirino; Agta Maddela of Maddela, Quirino; and Arta of Nagtipunan, Quirino. Northern Alta cultural communities, who found in Baler, Diteki and San Luis, Aurora, are not included in this study.

Central Luzon Negritos

The Central Luzon Negritos are the Negrito cultural communities of Bataan, Zambales, Pampanga and Tarlac provinces of the Central Luzon region. They are collectively referred to as the Ayta (or Aeta) Negritos, and speak a MP language that is classified under the Sambalic group. The five Ayta cultural communities included this study are the Ayta Ambala, Ayta Magbukon, Ayta Sambal, Ayta Mag-antsi, and Ayta Mag-indi. Ayta Ambala and Ayta Magbukon cultural communities are found in the province of Bataan. Outside of Bataan are the Ayta Sambal cultural communities in Botolan and Cabagan, Zambales; Ayta Mag-indi cultural communities in Floridablanca and Porac, Pampanga and in San Marcelino, Zambales; and Ayta Mag-antsi cultural communities in various towns of Tarlac, Zambales, and Pampanga. The Ayta group included in a recent genomic study18 likely involved the Ayta Mag-antsi and Ayta Mag-indi cultural communities of Pampanga and Tarlac provinces. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive genome-wide investigation of the Ayta Magbukon and Ayta Ambala ethnic groups.

Southern Luzon Negritos

The Southern Luzon Negritos include the Negrito populations residing in the Quezon and Rizal provinces of the Southern Luzon region. The Dumagat Agta of General Nakar, Quezon, Remontado Agta of Tanay, Rizal, and the Southern Alta of General Tinio, Nueva Ecija comprise the Southern Luzon Negritos represented in this study.

Southeast Luzon Negritos

The Southeast Luzon Negritos include the Negrito populations of the Bicol region and the Lopez municipality of Quezon province. In this study, the Southeast Luzon Negritos are represented by the cultural communities of Agta Lopez from Lopez, Quezon; Agta Manide from Jose Panganiban, Camarines Norte; Agta Isarog from Ocampo, Camarines Sur; Agta Iriga from Iriga City, Camarines Sur; Agta Iraya from Buhi, Camarines Sur; Agta Matnog from Matnog, Sorsogon; and Agta Bulusan from Bulusan, Sorsogon.

Phenotypically, Agta Bulusan and Agta Matnog appear more similar to the neighboring non-Negrito populations. These observations are supported by our f statistical, qpAdm, and Admixture analyses, where both groups display minimal Negrito and Denisovan ancestry. The levels of Negrito ancestry in both Agta Matnog and Agta Bulusan are similar to the levels found in neighboring non-Negrito Waray and Bicolano ethnic groups.

Southern Negritos

Southern Negritos are self-identified Negrito groups who inhabit the islands south of Luzon, such as the Batak of Palawan, the Ati of Panay and Negros Islands, and the Mamanwa of Mindanao. The Ati group in this study are represented by the cultural communities of Nagpana, Iloilo and Marikudo, Negros Occidental; while the Mamanwa and Batak are represented by the cultural communities of Lake Mainit, Surigao del Norte and Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, respectively.

Geologic Context of the Philippines and the rest of ISEA

The Philippines is an archipelago of 7,641 islands situated in the region of Island Southeast Asia (ISEA). Most of the Philippine Islands lie within the Philippine mobile plate, a complex section that is positioned between the tectonic boundaries of the Eurasian plate and the Philippine Sea plate. In contrast to the presence of dynamic seismic activity and volcanism at the plate margins of the Philippine mobile belt, the southwest section of the Philippines is more stable. This section includes the island of Palawan and those of the Sulu Archipelago. The Palawan micro-block and the Sulu micro-block form part of the northeast protrusions of the largely aseismic Sunda block.

In the course of past glacial cycles, the geography of the Philippines and the rest of ISEA has been modified by regional and global processes. Tectonic changes at the active plate margins, where the Philippine Islands lie, play some role in regional modifications. On a global scale, climate fluctuations influenced the magnitude of glaciation at the extreme latitudes, serving as the main factor determining the rise and fall of sea levels and the associated submergence or exposure of low-lying sections of landmasses70,71. The changes in sea levels, with a magnitude of up to 100-150 m, have their greatest impact on shallow continental shelves such as the large landmass of Sundaland72. These dramatic changes can influence the migration and settlement patterns of human populations, causing isolation and differentiation, bottleneck, or expansion.

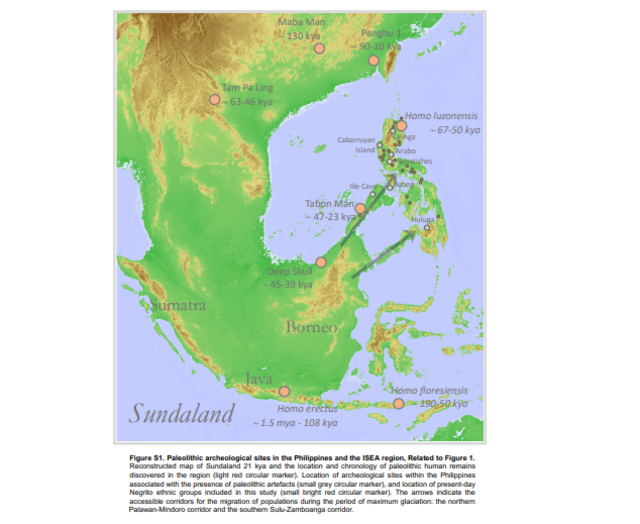

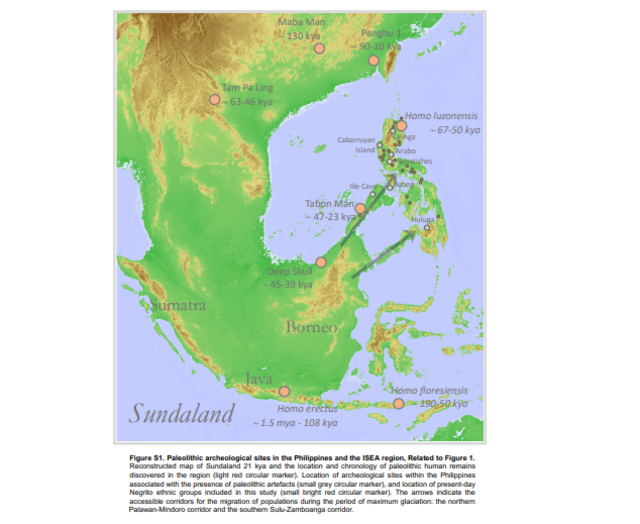

The location of past shorelines and the area extent of exposed landmasses was reconstructed using the information from earth rheology parameters that are appropriate for ISEA region, ocean-floor bathymetry using the GEBCO 30 ̋ global gridded data (https://www.gebco.net/data_and_products/), and inferred models of glaciation from 140 kya to the present73. For instance, the lower sea levels throughout the last glacial period have left the shallow continental shelves of the Sunda Block largely exposed11 (Figure S1): the Malay peninsula is interconnected with the present-day major islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo, forming one large biogeographical region of Sundaland. Gaining access to the Philippines from Sundaland only requires minimal water crossings, as narrow as ∼3 km during the last glacial maximum ∼21 kya. From northeast Borneo, the accessible pathways are either via the Palawan-Mindoro corridor or the Sulu Archipelago-Zamboanga Peninsula corridor. Given the recent period of deglaciation and the concomitant rise in sea levels, the more tractable pathway starting ∼14.5 kya is via the southern passage of the Sibutu-Basilan Ridge.

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 15, 2021 21:14:40 GMT

Paleolithic Archeology of the Philippines and the Surrounds The earliest evidence of hominin activity in the Philippines is currently located in the province of in northern Luzon74. The site was dated to ∼700 kya, and is characterized by an assemblage of in situ megafaunal fossils and lithic artifacts. A disarticulated skeleton of a local Rhinoceros species was shown to have evident cutmarks, which were attributed to anthropogenic butchery. Other archeological sites, though with limited stratigraphic information, occur throughout the Philippines; these include rockshelters, caves, and open sites containing stone artifacts (Figure S1). Likely Paleolithic sites include Arubo, Cabarruyan Island, Novaliches, Ille Cave, Bubog rockshelter, and Huluga75,76. The only Upper Paleolithic fossilized remains of Homo sapiens that have been recovered so far in the Philippines are the osteological materials from the Tabon cave site complex of Palawan Island77. Using Uranium-series (U-series) dating, three sets of human remains were directly dated to 16.5 kya, 31 kya, and 47 kya78. More recently, a third metatarsal hominin bone was recovered from the Callao Cave of Cagayan province, and was U-series dated to 67 kya34. A more comprehensive analysis of the twelve additional hominin elements from the same site revealed a combination of ancestral and derived morphological characteristics. The combination of these traits were not found in any known species of Homo, and hence was designated as a new species of Homo luzonensis35.  Outside of the Philippines, the Deep Skull from Niah Cave, Sarawak, Borneo is the oldest fossil of an anatomically modern human in ISEA79. The Deep Skull was dated to 45–39 kya based on direct U-series dating of the cranial bone and radiocarbon dating of charcoal from nearby sediments. The majority of other Paleolithic human remains discovered in the ISEA region are classified as archaic hominins. In the island of Java, several excavations from the 1890’s to the earlier part of the 20th century put forward the early discoveries of the Java Man, Ngandong Man, Mojorkerto child, and Sangiran 2 individual; all of which were recently characterized as having features belonging to the Homo erectus species80, 81, 82, 83 and dated to as recent as 108 kya84. In 2003, a 1.1 m-tall individual was discovered at Liang Bua on the island of Flores, Indonesia38, which was also defined as a new species of archaic hominins, coined as the Homo floresiensis. The skeletal remains of Homo floresiensis are dated to 50–100 kya, while the artifacts accompanying the skeletal remains are dated to 50–190 kya85, 86, 87. No fossilized remains of Denisovans was as of yet found in ISEA and Near Oceania. This is despite the fact that the region are inhabited by ethnic groups possessing the highest levels of Denisovan ancestry. Aside from the Altai Denisovan of Siberia, the only other direct evidence on the presence of Denisovans is the Xiahe individual from the Tibetan Plateau30,31. Our current knowledge on Denisovans is largely based on the high-coverage genomic data of Altai Denisovan from Siberia. Given the scant material that were established as definitively Denisovans, we presently carry limited information on the general physical features and phenotypic variability of Denisovans. We are not certain though whether some previously discovered archaic humans in the Asia-Pacific region may in fact be Denisovans or Denisovan-related. These fossilized remains contain some features that were either characterized as archaic or a combination of archaic and modern, which include, among others, the Dali, Maba, Xujiayao and Penghu-1 individuals30,32,33,88 (Figure S1). Moreover, it is not entirely impossible that the recently identified new species of archaic hominins in the ISEA region such as the Homo floresiensis of western Indonesia38 and Homo luzonensis of northern Philippines35, may also be Denisovans or Denisovan-related. To date, no ancient autosomal DNA material has been successfully extracted from any of these archaic fossils discovered outside of Siberia. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 16, 2021 4:19:50 GMT

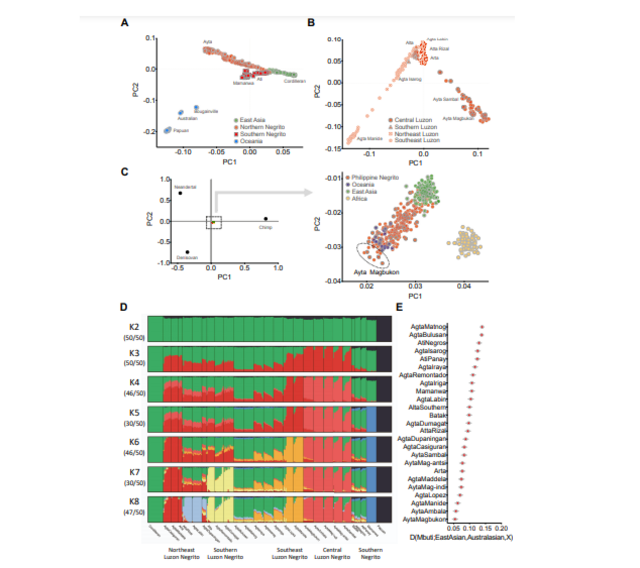

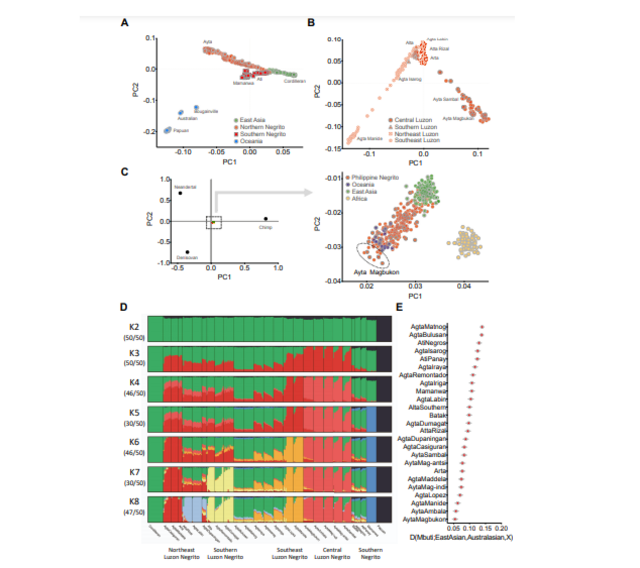

Admixture Analysis To determine the overall population structure of Philippine Negritos, we performed an unsupervised clustering method implemented in ADMIXTURE20 (Figure S2D). We included in the analysis all Philippine Negrito ethnic groups, and limited the number of individuals to 10 per population. In addition, we included 15 Cordillerans and 15 Papuans to serve as the least admixed reference for East Asians and Australasians, respectively. We ran a total of 50 iterations for each of the 8 clusters using the default settings. Common modes of replicates were identified using CLUMPP62, and the major mode for each K cluster was plotted using Pong v1.463.  Figure S2. Genetic affinities and clusters of Philippine Negrito ethnic groups, Related to Figure 1. Principal Component analysis (PCA) restricted to Australasians and East Asians (A), and to Northern Negritos of the Philippines (B). PCA applying the least square equations projection (C); modern humans are projected onto the first two principal components defined by the Altai Denisovan, Altai Neandertal, and chimpanzee. All modern humans lie at the center of the plot, and an inset panel to the right shows Ayta Magbukon to lie at the edge defined by Denisovan ancestry. Admixture analysis of Philippine Negritos (D) together with the reference populations representing the least admixed East Asian or Australasian, Cordillerans and Papuans, respectively. The analysis was ran for 50 iterations, and for each K, the common modes of replicates were identified using CLUMPP. The major mode for each K was then plotted using Pong v1.4. Detection of East Asian-related ancestry in all Philippine Negritos using the test D(Mbuti;EastAsian,Australasian,X), with Cordilleran Balangao as the surrogate for the least admixed East Asian and Papuan as the surrogate for the least admixed Australasian (E) Assuming two clusters (K2), the populations are split into black and green components, representing the Australasian and East Asian clusters, where the Papuans represent the least admixed Australasian and the Cordillerans represent the least admixed East Asian (Figure S2D). The Philippine Negritos acquire their own cluster at K3, which is represented by the red component. The Ayta of Central Luzon represent the least admixed Philippine Negritos. From K4 to K8, the Philippine Negritos are further split into the geographic clusters, with the appearance of Central Luzon Negrito cluster at K4 ((light red component, best represented by Ayta Magbukon and Ayta Ambala), the Southern Negrito cluster at K5 (blue component, best represented by the Mamanwa), the Southeast Luzon Negrito cluster at K6 (red component, best represented by the Agta Manide and Agta Lopez), the Southern Luzon Negrito cluster at K7 (yellow component, best represented by the Alta, Agta Dumagat, and Agta Remontado), and the Northeast Luzon Negrito clusters at K8 (red component represented by the Agta Maddela, Agta Casiguran and Arta and light blue component represented by Agta Labin and Atta Rizal). Our analysis reveal at least five distinct population of Philippine Negritos, based on the high support at K = 8 where we find 47 consistent results out of 50 iterations. At K = 8, the Northeast Luzon Negritos are even further subdivided into two clusters, making the total number of distinct Negrito clusters up to six. East Asian-related Admixture in Negritos To determine the presence of East Asian admixture among Philippine Negritos, we implemented the test D(Mbuti;EastAsian,Papuan,X); with Balangao Cordilleran utilized as a surrogate for the least admixed East Asian source (Figure S2E). We find that all Philippine Negritos display varied levels of gene flow from East Asians, with Ayta Magbukon presenting as the least admixed. To estimate the levels of East Asian and Australasian-related ancestries in Negritos, we implemented the qpAdm22 tool of Admixtools v5.0 software package. We first prepared a new dataset with reference ancient samples, by merging Phil_1KGP_SGDP_1.92M dataset with published ancient DNA data to produce the Phil_1KGP_SGDP_Ancient_1.92M dataset, which was then haploidized and filtered to keep transversion sites only, producing the Phil_1KGP_SGDP_Ancient_Transv_317K dataset with 317,220 SNPs. The ‘left’ populations include Balangao Cordilleran of the Philippines as the surrogate for the least admixed East Asian source and Papuan as the surrogate for the least admixed Australasian source. The outgroup or ‘right’ populations include Juhoansi, Mbuti, Mota, Loschbour, Anzick1, Ust’Ishim, Sumiduouro8, and Karitiana. Overall, there is a wide variation in the magnitude of admixture with East Asians. For instance, Ayta Magbukon and Ayta Ambala presented as the least admixed Negrito populations, with an East Asian-related ancestry of only ∼10%–30% (Figure 1D). On the other hand, both Agta Bulusan and Agta Matnog have the highest levels of admixture, possessing ∼79%–85% East Asian-related ancestry. To estimate the date of admixture, we utilized MALDER91, which applies a weighted linkage disequilibrium (LD) statistic-based method and allows detection of multiple admixture events. Philippine non-Negritos, Amis, Atayal, mainland East Asians, and Australopapuans were set as putative source populations, while all Philippine Negrito groups were set as target populations. The mean date of admixture between Negritos and East Asians among all ethnic groups within the Philippines was estimated to ∼2,281 years (95% CI: 2,083 – 2,523 years). |

|