|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 22, 2021 20:13:41 GMT

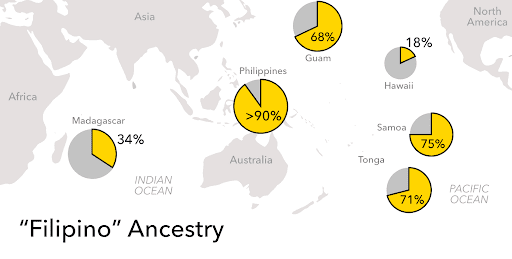

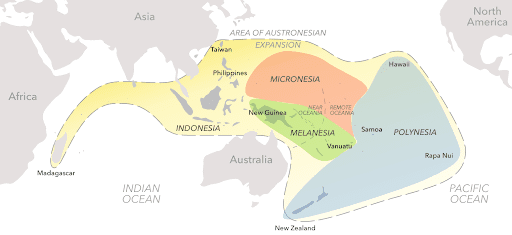

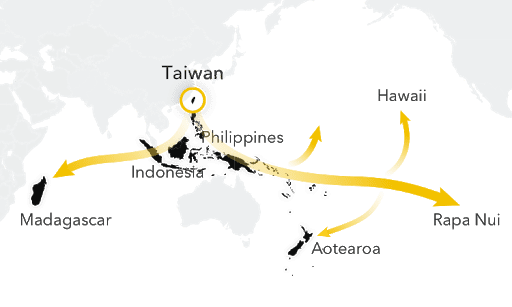

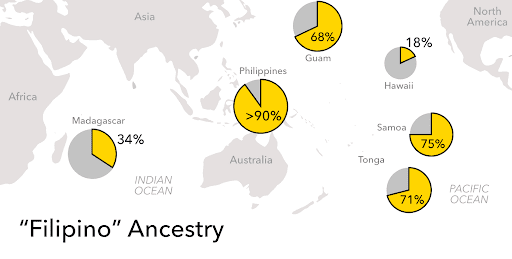

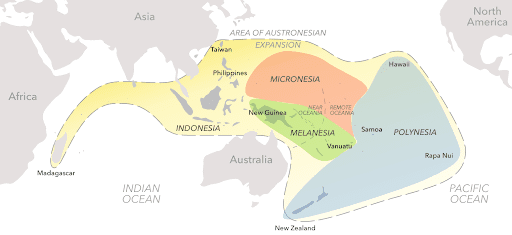

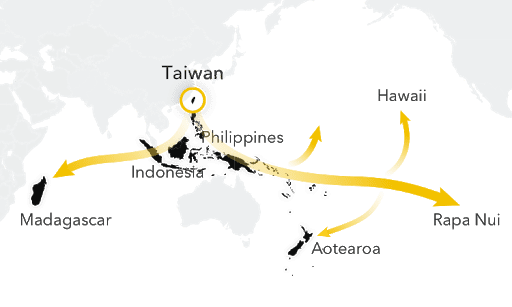

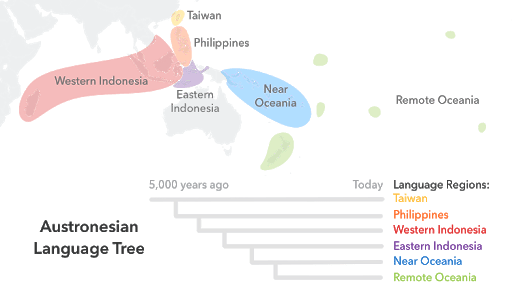

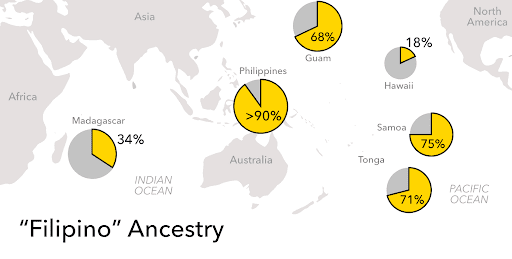

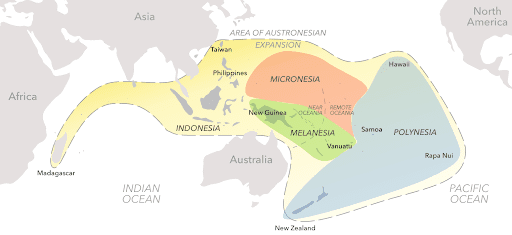

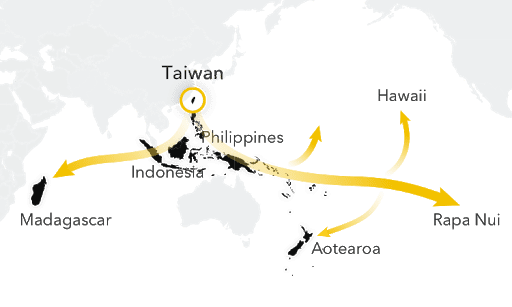

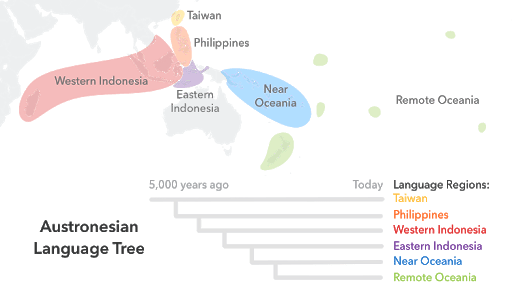

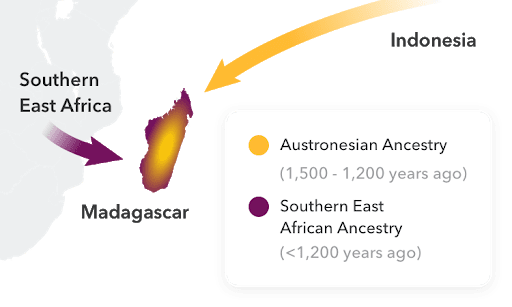

It was true that people with the highest proportion of “Filipino” in their ancestry estimates were actually of Filipino descent (over 90 percent on average), but this so-called “Filipino” ancestry reached an average of 75 percent in customers from Samoa, 71 percent in Tonga, 68 percent in Guam, 18 percent in Hawaii, and even 34 percent among customers from Madagascar, off the southeastern coast of Africa.  Clearly, this update was not just identifying Filipino ancestry, but a shared genetic heritage that was spread across nearly two-thirds of the circumference of the globe. Our ancestry scientists realized right away that this shared ancestry was a reflection of human migration and the major expansion of seafaring people who spoke Austronesian languages that began around 5,000 years ago near Taiwan and spread across a vast part of the world. We renamed the population to “Filipino & Austronesian,” and the population description was updated to shed light on this shared linguistic, genetic, and cultural history.  Here are our favorite stories about the “Austronesian Expansion,” from out-of-this-world navigation techniques to the gut bacteria that hitched a ride across the sea. The Final Frontier Around 5,000 years ago, Austronesians began a millennia-long expansion into the Pacific from Taiwan. They carried their knowledge of navigation and farming more than halfway around the world. They expanded through the Philippines and Indonesia all the way to Hawaii in the east and Madagascar in the west. During this expansion, the Austronesians mixed with people they met along their way, including the indigenous Filipinos, Papuans (whose ancestors are thought to have arrived over 50,000 years ago), and Southeast Asian mainlanders. Polynesian culture later emerged from Austronesian societies in Tonga and Samoa. It spread to the equatorial islands of the central Pacific — including French Polynesia — as recently as 1,000 years ago. Soon after, Polynesians settled the far-flung lands of Hawaii, Aotearoa (New Zealand), and Rapa Nui (Easter Island). This late, rapid settlement is thought to explain the remarkable similarities between the cultures and languages of the remote Pacific.  Way-finders Long before the European Age of Exploration, Polynesian voyagers were crossing thousands of miles of uncharted water, settling one uninhabited island after another. Almost all knowledge of traditional Polynesian navigation is lost to time, but their techniques likely included: “Wave-piloting,” which involves sensing the reflections and refractions of ocean swells off of distant islands. Following birds or turtles to land. Spotting island-hugging bioluminescence. Relying on memorized star maps as a guide — a skill highlighted in the 2016 animated film, Moana. Only a handful of Pacific Islanders carry the traditional knowledge of wave piloting, but in 2006, researchers accompanied a Marshallese wave pilot on a journey between islands. To navigate the journey, the wave pilot relied only on his ability to read the ocean swells. In a test of the wave pilot’s skill, the researchers set the ship miles off-course while the navigator slept. But soon after he woke up, the wave pilot had the ship back on course, having correctly interpreted the pattern of waves reflecting off a nearby island.  |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 22, 2021 21:11:58 GMT

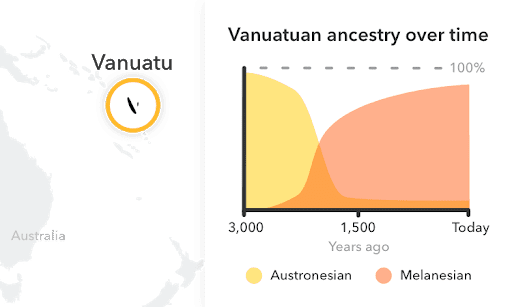

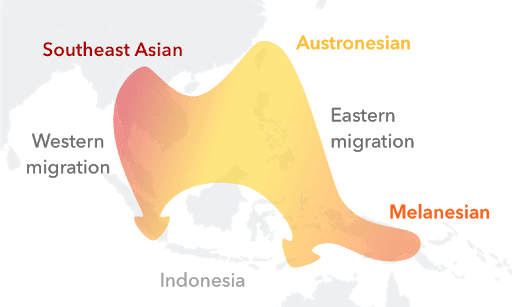

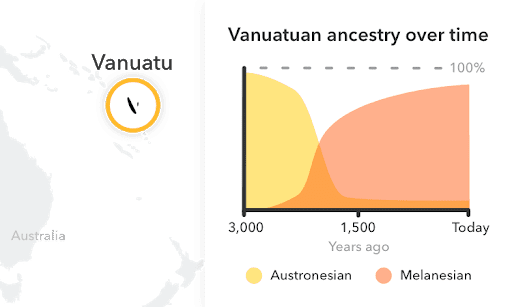

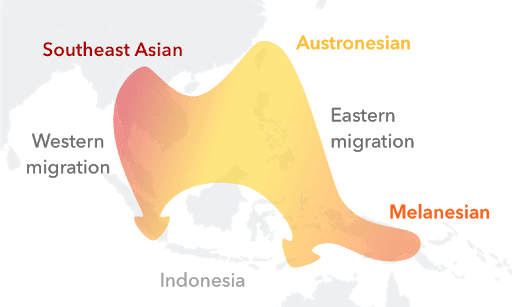

Language on the move Before DNA shed light on the origins of Austronesians, studies of their languages pointed to an Austronesian origin closely related to the indigenous people of Taiwan. A team of scientists in New Zealand built a database of simple words from 400 Austronesian languages, and by focusing on cognates (similar words that mean the same thing), the team was able to build a family tree of Austronesian languages — with indigenous Taiwanese Formosan languages at the root. Branching from there were the languages spoken in the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea, Fiji, and finally, the closely related Polynesian languages, such as Samoan, Maori, Tahitian, and Hawaiian. This language tree mirrors the genetic relationships of a number of other living things found throughout the Pacific — from gut bacteria to paper mulberry plants (used to make barkcloth). Researchers believe these different organisms originated in Taiwan and hitched a ride across the Pacific with the Austronesian voyagers.  Melanesian Exchange The ancestors of Melanesians — the indigenous inhabitants of Near Oceania — reached the islands of the western Pacific much earlier than the Austronesians. They arrived on these islands well over 50,000 years ago. Today this ancestry is common in populations from Papua New Guinea to Fiji, a distance spanning over 2,500 miles. But, the oldest human remains found on Vanuatu (an archipelago between New Guinea and Fiji) and on islands further East aren’t Melanesian. So when did the Melanesians reach Vanuatu and who was there before them? A recent study of ancient human remains from Vanuatu showed that Austronesian settlers first reached Vanuatu around 3,000 years ago. Soon after, people with Melanesian ancestry began to arrive. Today, even though Vanuatuans speak primarily Austronesian languages, they have mostly Melanesian ancestry. It seems that early Melanesian voyagers halted their eastward migration in the Solomon Islands. They only ventured further into the Pacific after a new wave of voyagers — the Austronesians — passed through the region to settle Vanuatu, Tonga, and other remote Pacific islands. Today, almost all populations in the remote Pacific have more than 25 percent Melanesian ancestry. This is despite initial settlement by Austronesians.  Indonesian Melting Pot Indonesia is genetically diverse. This is not particularly surprising for a 3,000-mile-wide nation made up of more than 17,000 islands. Austronesian ancestry is found throughout Indonesia. But where the inhabitants of the large western islands have strong genetic ties to the Southeast Asian mainland, the inhabitants of the islands east of Bali have very little. The most likely scenario is that a western group of Austronesian voyagers mixed with people in southern Vietnam or the Malay Peninsula. This mixed population likely continued on to settle western Indonesia. Eastern Indonesia, on the other hand, is home to people with a combination of primarily Austronesian and Melanesian ancestry. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 22, 2021 21:58:46 GMT

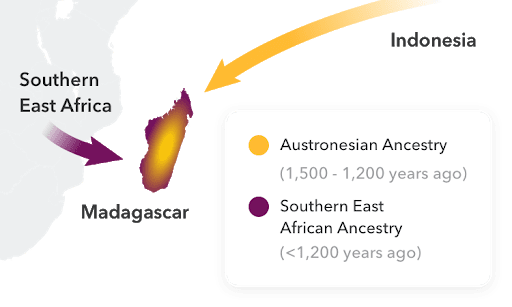

The Malagasy Mystery The Malagasy people of Madagascar speak an Austronesian language, but Madagascar is a world away from Southeast Asia. Malagasy people also have African ancestry. So who reached Madagascar first and where did they come from? Although the African continent is much closer, there is cultural, genetic, archaeological, and linguistic evidence pointing to an initial settlement of Madagascar by Austronesian voyagers between 1,200 and 1,500 years ago. This was followed by the arrival of Bantu speakers from southern East Africa.  Linguistic and genetic studies showed that the Austronesian founders of Madagascar were most closely related to present-day groups living in central and eastern Indonesia (1, 2, 3). These studies also revealed that African ancestry is generally higher in Madagascar’s coastal lowlands. Austronesian ancestry reaches higher levels in the country’s central highlands. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 23, 2021 6:09:01 GMT

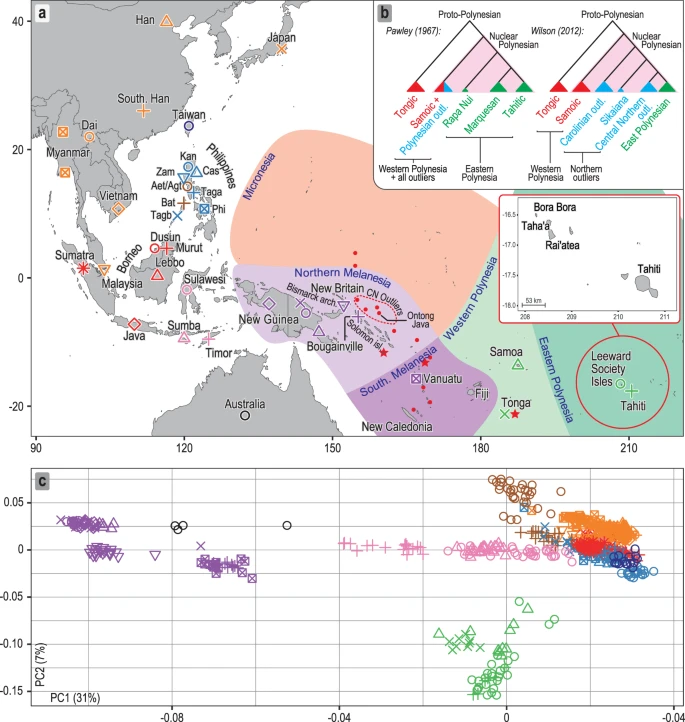

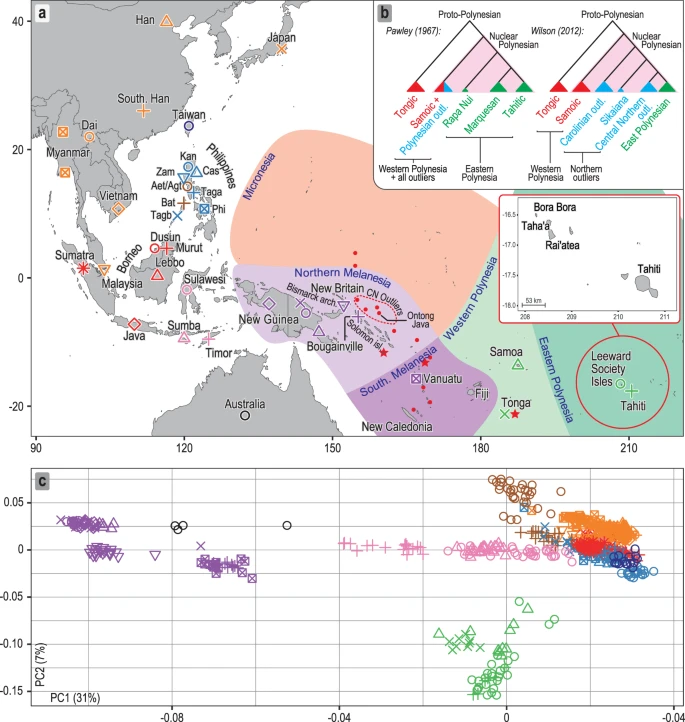

Investigating the origins of eastern Polynesians using genome-wide data from the Leeward Society Isles Georgi Hudjashov, Phillip Endicott, Helen Post, Nano Nagle, Simon Y. W. Ho, Daniel J. Lawson, Maere Reidla, Monika Karmin, Siiri Rootsi, Ene Metspalu, Lauri Saag, Richard Villems, Murray P. Cox, R. John Mitchell, Ralph L. Garcia-Bertrand, Mait Metspalu & Rene J. Herrera Scientific Reports volume 8, Article number: 1823 (2018) Abstract The debate concerning the origin of the Polynesian speaking peoples has been recently reinvigorated by genetic evidence for secondary migrations to western Polynesia from the New Guinea region during the 2nd millennium BP. Using genome-wide autosomal data from the Leeward Society Islands, the ancient cultural hub of eastern Polynesia, we find that the inhabitants’ genomes also demonstrate evidence of this episode of admixture, dating to 1,700–1,200 BP. This supports a late settlement chronology for eastern Polynesia, commencing ~1,000 BP, after the internal differentiation of Polynesian society. More than 70% of the autosomal ancestry of Leeward Society Islanders derives from Island Southeast Asia with the lowland populations of the Philippines as the single largest potential source. These long-distance migrants into Polynesia experienced additional admixture with northern Melanesians prior to the secondary migrations of the 2nd millennium BP. Moreover, the genetic diversity of mtDNA and Y chromosome lineages in the Leeward Society Islands is consistent with linguistic evidence for settlement of eastern Polynesia proceeding from the central northern Polynesian outliers in the Solomon Islands. These results stress the complex demographic history of the Leeward Society Islands and challenge phylogenetic models of cultural evolution predicated on eastern Polynesia being settled from Samoa. Introduction The cultural and linguistic unity of the islands and atolls of the central Pacific was first documented in detail by Johann Reinhold Forster, a naturalist on James Cook’s second voyage of discovery to the Pacific (1772–1775). He suggested that the similarity of the languages spoken there, now known as Polynesian, reflected a comparatively shallow time-depth since their dispersal1. Forster’s seminal comparative study of Austronesian languages identified the lowland region of the Philippines in Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) as the ultimate source for the Polynesian languages and proposed a long-distance migration from there by the ancestors of today’s Polynesian speakers. This appeared to be the only explanation for the striking difference in phenotype that he observed between the peoples of the central Pacific and those of the intervening region, which is now known as Melanesia. Herein, the terms Melanesia and Micronesia are used in their geographical sense. We use the term Polynesia to include all islands and atolls whose inhabitants speak Polynesian languages, including 23 found throughout Melanesia and Micronesia, referred to as outlier Polynesia (Fig. 1a). Figure 1  Sampling locations and overview of genomic diversity. (a) Sources of population data used in the present study. The Philippine group names are abbreviated as follows: Aet (Aeta); Agt (Agta); Bat (Batak); Cas (Casiguran); Kan (Kankanaey); Taga (Tagalog); Tagb (Tagbanua); Zam (Zambales); and Phi (Philippines, incorporating all other groups from this region). Colours indicate regional affiliation of populations used for analysis of autosomal DNA: orange – mainland Southeast Asia and East Asia; dark blue – Taiwan; brown – Philippines Aeta, Agta and Batak negritos; light blue – Philippines non-negritos; red – western Indonesia; pink – eastern Indonesia; purple – northern Melanesia and New Guinea; black – Australia; green –Polynesia. The usage of populations varies with the type of analysis employed (Supplementary Table S1). Inset map shows the three populations from the Leeward Society Isles, and Tahiti, the major island in the Windward Society Isles. The red circles within Micronesia and Melanesia represent 20 of the atolls and islands referred to collectively as outlier Polynesia. The red stars denote the three additional Polynesian outlier populations (Rennell and Bellona, Tikopia), which together with Tonga, were used in analysis of ancient admixture by Skoglund, et al.25. Detailed sample information is given in Supplementary Table S1. The map was created using R v. 3.4.1 (R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, www.R-project.org/), and packages ‘maps’ v. 3.2.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/package=maps) and ‘mapdata’ v. 2.2-6 (https://cran.r-project.org/package=mapdata). (b) Inset at top right shows two alternative reconstructed sub-groupings of Polynesian languages discussed in the text. The critical differences are the position of the East Polynesian languages relative to the rest of nuclear Polynesian, and their relationship to the Central Northern Outlier languages. In the sub-grouping according to Pawley31 all the Polynesian Outlier languages group within Samoic implying an early separation of Proto-East Polynesian from the rest of the Nuclear Polynesian languages. In the alternative sub-grouping proposed by Wilson32 the Central Northern Outlier languages group with the languages of East Polynesia, within a larger clade containing the other Northern Outlier languages. (c) Principal components analysis of genome-wide SNP diversity in 639 individuals populations shown in panel A; axes are scaled by the proportion of variance described by the corresponding principal component. Separating the demographic histories of Polynesia and Melanesia became difficult to sustain with developments in archaeology during the second half of the 20th century. These established that the settlement of southern Melanesia (Santa Cruz, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Fiji) and western Polynesia (Tonga, Samoa, Niue and Futuna) is marked by the same archaeological horizon, known as the Lapita Cultural Complex (LCC). The LCC first appears in northern Melanesia (the Bismarck Archipelago, Bougainville, and the Solomon Islands main chain) ~3,450–3,250 BP, and quickly spread into southern Melanesia ~3,200–3,000 BP, reaching Tonga and Samoa ~2,900 BP2,3,4. At the same time, the study of comparative linguistics has shown that the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian phylum of languages, of which Polynesian is a member, is spoken throughout most of Melanesia and parts of coastal New Guinea, and appears to be a recent intrusion from ISEA5. So while there is considerable overlap between the distributions of the LCC and the Oceanic languages, there remains a phenotypic divide between southern Melanesia and western Polynesia, which is observed between Fiji and Tonga6,7. A central theme in this debate is the extent to which the development of the LCC involved local people in the Bismarck Archipelago of northern Melanesia8,9,10. An alternative is that the LCC represents the arrival of a largely pre-formed cultural package carried by speakers of proto-Oceanic languages from Taiwan, via the Philippines, in ISEA11. Hypotheses are placed on a continuum from a dendritic, radiating, phylogenetic model of cultural evolution that relies on the relative isolation of populations12, to one based on complex ongoing biological and cultural interaction between groups, leading to reticulated networks of genes and culture9. A compromise position has been promoted by the recognition of a Lapita homeland in the Bismarck Archipelago10, together with evidence that the genomes of contemporary Polynesians contain 20–30% ancestry typical of northern Melanesia and New Guinea13,14. This posits a period of limited cultural and genetic admixture involving migrants from ISEA during the early LCC phase in northern Melanesia ~3,450–3,250 BP15. Polynesian society then developed in relative isolation following the pioneering settlement of Tonga and Samoa ~2,900 BP1. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 23, 2021 20:52:02 GMT

Genetic evidence for this intermediate model is provided by the presence of members of Y chromosome haplogroup (hg) C2a-M208, together with its daughter lineage C2a1-P33, among Polynesian speakers16,17. This is seen as a proxy for male-mediated admixture from northern Melanesian and New Guinean sources into the gene pool of migrants from ISEA during the formative period of the LCC in the Bismarck Archipelago, prior to the settlement of southern Melanesia and western Polynesia13,18. In contrast, the near fixation in Polynesian speaking groups of the mitochondrial lineage B4a1a1 is seen as evidence of a predominantly ISEA maternal heritage13,19. Subsequent research, however, has shown that B4a1a1 is widespread throughout northern Melanesia20, including regions that show no evidence of autosomal admixture with people from ISEA21. Alternatively, therefore, hg B4a1a1 might also have been present in northern Melanesia before the emergence of the LCC22,23. Similar ambiguity now exists over the origins of paternal lineage C2a-M208, due to its presence in ISEA24 and rather low overall frequencies in the Bismarck Archipelago and coastal New Guinea17.

An important advance in this debate is the recovery of ancient genomic DNA from LCC contexts on Vanuatu (~2,900 BP) (n = 3) and post-Lapita Tonga (~2,500 BP) (n = 1), since the results indicate people with close to 100% ancestry related to an ISEA heritage25. These data show that some settlers of the LCC period appear to have transited northern Melanesia and New Guinea from ISEA without receiving any significant amounts of genetic admixture. A second major finding is that the 20–30% ancestry originating from northern Melanesia and New Guinea, detected in contemporary genomes from the eastern fringe of southern Melanesia and western Polynesia, appears to have arrived during the 2nd millennium BP (1,900–1,200 BP). This result is consistent with post-LCC movements of people into southern Melanesia and western Polynesia, in a process of polygenesis, being responsible for the differences in phenotype observed between the two regions6.

The potential significance of this proposed post-LCC migration for the phylogenetic approach to cultural evolution cannot be overstated. This is because the model is based on an Ancestral Polynesian Society (APS) developing in a western Polynesian homeland during the mid 3rd millennium BP, followed by a rapid settlement of eastern Polynesia ~2,200 BP12. The settlement of eastern Polynesia, however, has witnessed significant reductions in the earliest secure radiometric dates in recent years. These currently stand at ~950 BP and come from Rai’atea in the Leeward Society Isles26,27, thereby excluding the original calibration for the model and subsequent revisions to it28. The archaeology for the phylogenetic model can also be challenged because the evidence post 2,500 BP suggests isolation of Tonga and Samoa, rather than the interaction invoked for the development of Proto-Polynesian language29. By ~950 BP, society in western Polynesia was differentiated, both culturally and linguistically, indicating that, if this late chronology is accurate, the source population for eastern Polynesia was likely a regional group rather than the hypothetical APS29,30.

A central component of the original phylogenetic model is the long-standing sub-grouping of the Polynesian languages. The initial divergence of Nuclear Polynesian from the Tongic languages is followed by a second-order split, between Proto-East Polynesian (Rapa Nui, Marquesan and Tahitic) and the rest of the Nuclear Polynesian languages (Samoic and all the Polynesian outlier languages)31 (Fig. 1b, left-hand tree). This sub-grouping recognizes the separation of Tongic and Samoic but is difficult to reconcile with a settlement of eastern Polynesia commencing ~950 BP, since it necessitates the second-order split, involving Proto-East Polynesian, to occur up to ~1,200 years earlier. An alternative linguistic sub-grouping that places the East Polynesian languages together with those of the central northern outliers (east coast of the northern Solomon Islands) provides a potential solution for the apparent discordance between archaeology and language32,33 (Fig. 1b, right-hand tree). This also challenges the orthodoxy within Polynesian studies that eastern Polynesia was settled directly from Samoa11,12,28. For Kirch and Green28, Samoa is ancient Hawa’iki, the cradle of Polynesian culture. In contrast, for Wilson32 Hawa’iki represents the ancient name for the Leeward Society Isles, which are referred to as the cultural and spiritual hub of eastern Polynesia in oral histories of the region, from where other islands and atolls were settled34.

The Leeward Society Isles, therefore, are of central importance to understanding the reasons for these conflicting signals from archaeology and language. If the ancestors of the Leeward Society Islanders experienced the same episode of ancient admixture as people in western Polynesia and outlier Polynesia during the mid 2nd millennium BP25, this would support the late settlement chronology. In this study, we report the first genomic data from Bora Bora, Rai’atea and Taha’a, three of the Leeward Society Isles. We use the analysis of genotype and haplotype data to ascertain whether the signals of admixture present in these eastern Polynesian populations are similar to those from western and outlier Polynesia and identify potential donors to the ancestors of the Leeward Society Islanders. Further insights into the demographic history of eastern Polynesia is provided by the first deep re-sequencing of Polynesian Y chromosomes, complemented by high-resolution genotyping of key paternal and maternal lineages from the Leeward Society Isles and New Zealand.

|

|