|

|

Post by Admin on May 3, 2020 5:31:38 GMT

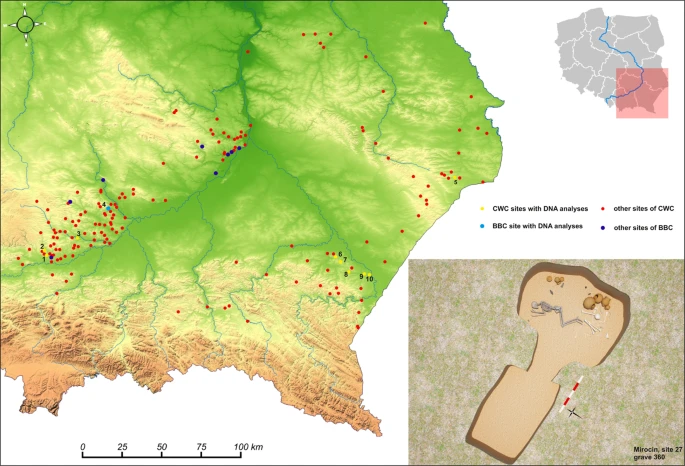

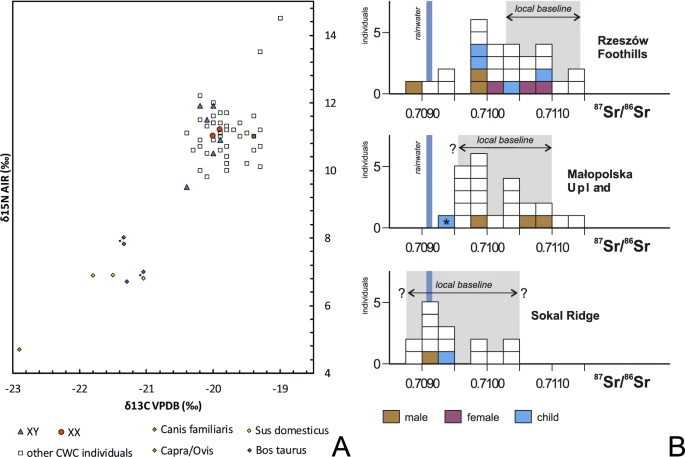

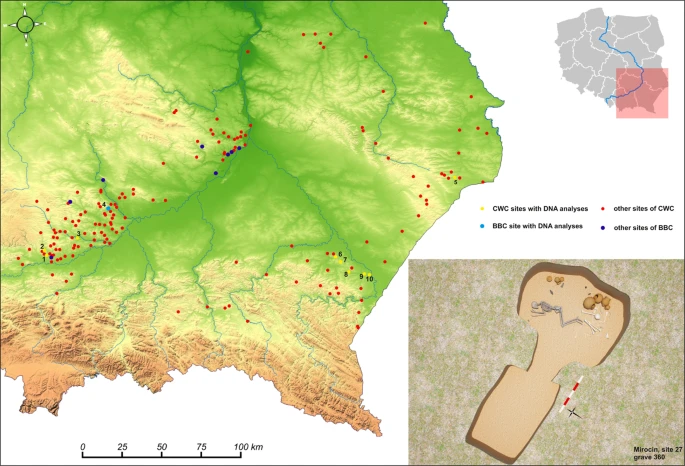

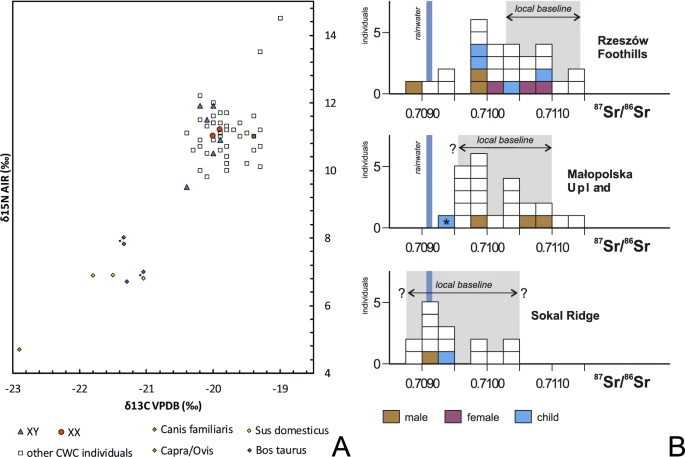

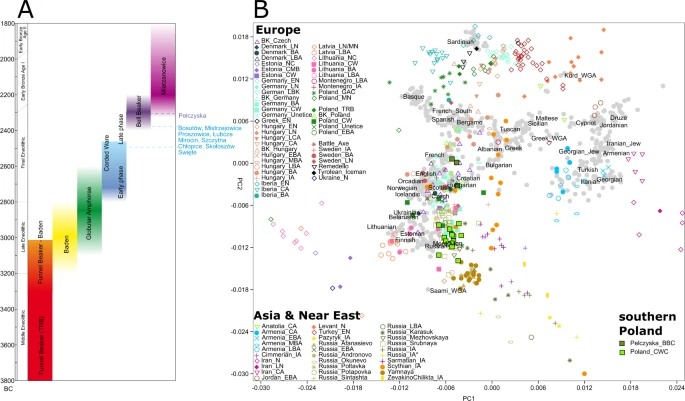

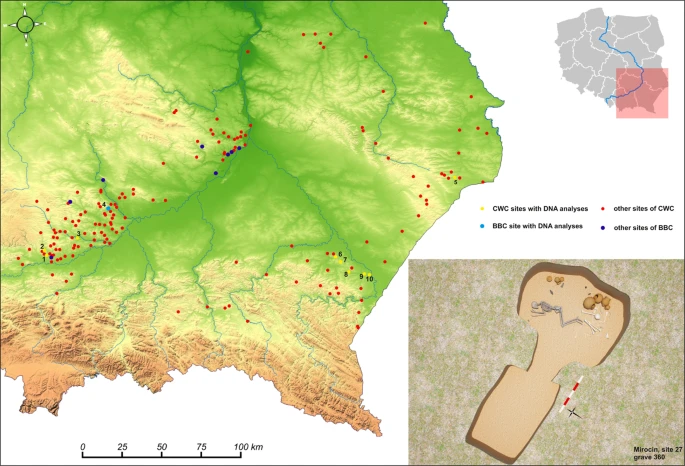

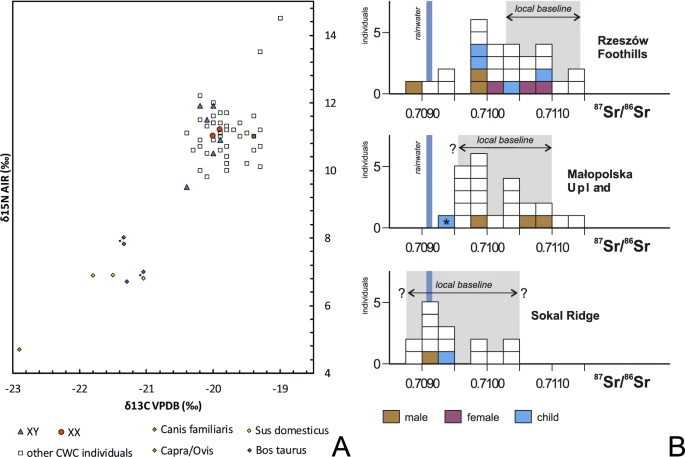

Materials Samples of the petrous portion of the temporal bone were taken from 50 individuals representing the Corded Ware Complex (CWC) and 3 individuals representing the Bell Beaker culture (BBC) buried in graves in south-eastern Poland. We have obtained genetic data from 19 individuals (16 of CWC and 3 of BBC). All examined individuals come from three geographical regions (Fig. 1; Table 1; Table S1): the Rzeszów Foothills (part of the Subcarpathian Region; sites of Szczytna, Chłopice, Mirocin and Święte), the Małopolska Upland (Mistrzejowice, Proszowice, Bosutów, Pełczyska) and the Sokal Ridge (the western part of Volhynian Upland – site of Łubcze) (Supplementary Information – Materials; Figs. S1–S13). All burials are of similar type exhibiting the same funeral rite with some differences concerning grave goods and their radiocarbon dates coincide (Table 1; Supplementary Information - 14 C Dating; Table S2, Fig. S15). The Strontium isotope (Sr) analyses included human enamel samples obtained from 16 individuals who were selected for sampling based on preserved dental enamel and availability of contextual information. Among them were females and males, predominantly of adult and mature individuals, and also children. Enamel was taken from first molars (M1) whenever possible and occasionally from first premolars (P1) (Supplementary Information – Strontium Isotopes; Table S4, Fig. 2). Moreover carbon (δ13Ccoll) and nitrogen (δ15Ncoll) stable isotope analyses were performed for 8 individuals (Supplementary Information – Stable isotopes – diet; Table S5, Fig. 2A). We investigated patterns in the genetic variation in relation to geographical subgroupings based on archaeological information but also the genetic data in relation to the other results obtained through the stable isotope (Sr) analyses and radiocarbon dating. The groups are listed in Table 1. In short, we first divided individuals based on geographical and archaeological context into four groups (Groups I-IV), and in addition introduce a division based on results from the strontium analyses (Groups Ia, IVa and V): For more details regarding tested groupings and obtained results, see section Grouping individuals according to their provenance (Sr isotopes).  Figure 1 The relief map of south-eastern Poland with marked location of archaeological sites of the CWC and BBC cultures. 1 – Kraków-Mistrzejowice, 2 – Bosutów, 3 – Proszowice, 4 – Pełczyska, 5 – Łubcze, 6 – Mirocin, 7 – Szczytna, 8 – Chłopice, 9 – Skołoszów, 10 – Święte. Reconstruction of niche grave 360 from Mirocin, site 27 (drawn by K. Rosińska-Balik).  Figure 2 (A) Variation in carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions of the bone collagen of humans and animals of the Corded Ware Complex from south-eastern Poland. Individuals with DNA profiles (XX, XY) are indicated. (B) Strontium isotope composition (87Sr/86Sr) of human enamel of the CWC populations from the Rzeszów Foothills, Małopolska Upland and the Sokal Ridge. A child from the BBC grave at Pełczyska is asterisked. Individuals investigated during the present study are coloured. Other isotopic data and local baselines (in grey) are from Belka et al.41, Szczepanek et al.29 and results of unpublished investigations of the authors. The Sr isotope composition of rainwater is indicated. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 3, 2020 20:27:07 GMT

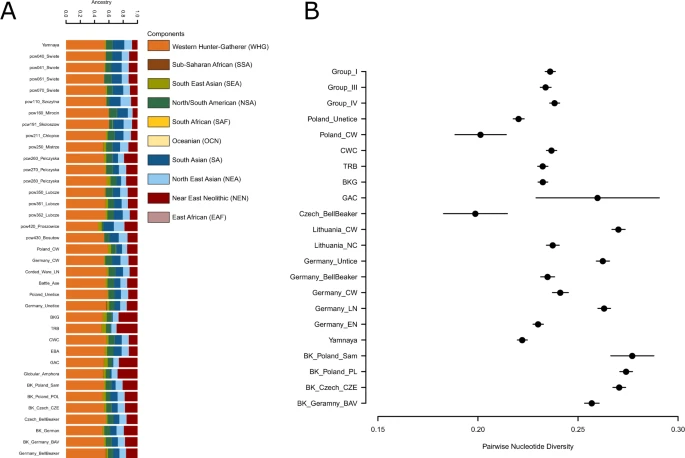

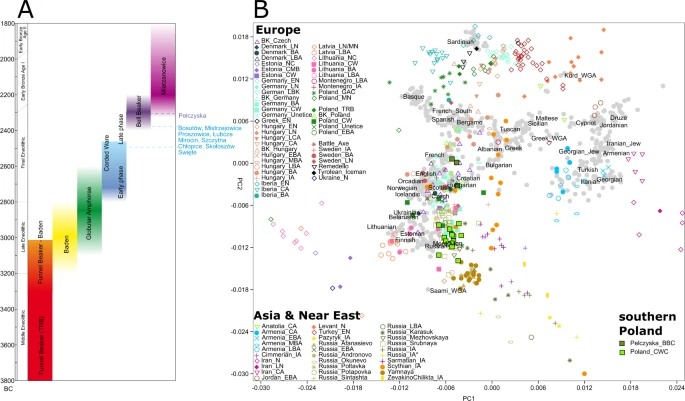

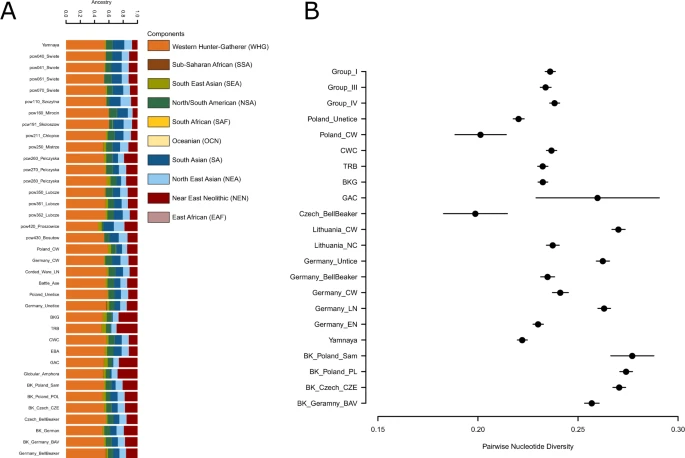

Results We collected bone samples from 53 individuals and produced low to medium coverage whole genome sequence data with coverages ranging between 0.02x to 5.4x for 19 Final Eneolithic/Bronze Age individuals from the ten sites in southern Poland. Ten of 19 sequenced individuals were radiocarbon dated from 3985 ± 35 to 3830 ± 35 BP (Fig. S14, Tables S2, S7). Obtained genetic sequences displayed cytosine deamination patterns characteristic of ancient DNA (Fig. S17)8,30,31,32. Mitochondrial (mtDNA) DNA-based contamination levels were calculated based on private polymorphism characterization (13 individuals with sufficient mtDNA coverage)33, and sequence mapping likelihood estimation34. The obtained contamination estimates varied between 0–3.6% (95% CI of 0–7.3%) and all individuals carried sequences with >90% (>97% in 14 individuals) probability of being authentic (Table S10). Thus, the obtained genomic data were deemed authentic and all sequenced individuals were included in population analyses. All Eneolithic individuals from Poland carried mtDNA lineages of European or West Eurasian origin35 including H (including H2 and H7), HV, I2, J1, K1, T1, T2, U4, and U5 (Table S8). Individuals from Pełczyska exhibited the same mtDNA haplogroups identified at other CWC sites. In contrast to individuals of the Yamnaya complex the CWC and BBC individuals from southern Poland carried I2 and J1 lineages, but lacked the mtDNA haplogroups W and U2, often found in Yamnaya individuals1,10,36. Molecular sex was assigned in all 19 individuals37 of which ten were sub-adults and therefore lacking prior osteological sex assessments. Eight individuals were female (XX) and 11 individuals were male (XY). The Y chromosome haplogroup was assigned in nine males of which all belonged to macrohaplogroup ‘R’ (Table S9). In seven individuals the Y chromosome haplogroup was further narrowed down to lineage R1b-M269 or R-L11 characteristic of Yamnaya and Bell Beaker individuals5,10 and particularly widespread throughout Eurasia since the Bronze Age38. In order to investigate mutual relations between individuals we employed conditional nucleotide diversity estimates which is calculated between all pairs of individuals investigated in this study7 (Table S11). Here an average number of mismatches between pairs of individuals was estimated based on sites in Human Origins dataset and in Yoruban individuals from 1000 Genomes Project (Table S11)39. The results did not reveal strong structuring between sites but highlighted closer relationships between a number of individuals (pcw040-pcw041, pcw061-pcw062 and pcw211-pcw212). Additionally, reduced conditional diversity was observed between an individual from Proszowice (pcw420) and individuals from Święte (pcw062, pcw110) and Skołoszów (pcw191). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) In order to investigate and visualize genetic relations between our Polish Corded Ware individuals and both present-day and ancient populations we performed PCA on the autosomal genomic data (Figs. 3B, S21, S22). The PCA suggests that (a) despite geographical proximity there is a distinct genetic separation between CWC and BBC individuals from Southern Poland. (b) the genetic variation of CWC individuals from southern Poland overlaps with the majority of the published CWC individuals from Germany while the eight published CWC individuals from Poland10,11 show a closer similarity to BBC representatives (Fig. S20) (c) the genetic variation of BBC individuals from southern Poland overlaps with the broad variation of BBC individuals from Central Europe (Czech Republic, Germany, Poland and Hungary) (Fig. S21). Based on the archaeological, geographical and genetic results we further ran tests according to cultural division (two groups: CWC and BBC) and geographical distribution of sites (four groups: Group I-IV) (Table 1).  Figure 3 Admixture In order to trace ancestral whgs of the samples we performed ADMIXTURE analyses between 2 K and 10 K using 10 replicates per run with the total of 214 world-wide modern populations and 485 ancient individuals grouped into 123 populations/individual samples. As expected the Admixture analyses showed that Polish Eneolithic individuals were carriers of three major components: West and North European HG (WHG; orange), Near East Neolithic (NEN; red), blue and green components of Asian origins (SA – South Asian - navy blue; NEA - North East Asian - light blue; SEA – South East Asian - light green and NSA –North/South American – dark green). In that respect, they were similar to earlier published Admixture analyses11 and revealed that individuals from Święte, Szczytna and Mirocin were carriers of larger NEN and SEA components than the representatives of Yamnaya. Polish CWC individuals also had traces of yet another component which is most prominent in Sub-Saharan and other modern African populations. According to earlier research the component was found to be more evident in Neolithic European populations than those with Steppe ancestry. In terms of differences between groups of individuals it seems that members of Group I carried larger proportion of SA and less of SEA component, while individuals in Groups III and IV had larger SEA and NEN components. This variation is mirrored by variation and component distribution patterns observed in previously published individuals form central European Neolithic (Figs. 4A, S23). Our findings point to variable local admixture patterns between earlier Neolithic populations from southern Poland and incoming Steppe nomads as well as structuring between CWC groups form different parts of present-day Poland.  Figure 4 A pruned visualisation of the admixture run of the whole dataset at K = 10 (Fig. S23). The bar plot shows newly published data from Poland as well as previously published individuals from Poland, Yamnaya, Battle Axe cultures and Corded Ware, Bell Beaker individuals from Germany and Czech Republic (A). Conditional nucleotide diversity in Groups I, II and IV compared to diversity estimates from other closely related population groups (B). f 2-, f 3- and f 4-statistics We tested with outgroup f3-statistics, which ancient population/individuals shared more genetic drift with the ancient samples generated here individually. The different population size between the reference ancient population/individuals and the lack of significant results between closely related individuals and populations make it difficult to extract conclusions from these analyses. Therefore, we grouped our ancient individuals into four groups (groups I-IV) based on the aforementioned geographical distribution of the sites and compared these groups between them and also with the ancient reference individuals and populations. Ancient reference individuals were merged into groups following the same criteria as in the ADMIXTURE analyses. Overall, although non-significant the results suggested a trend where the four groups share more genetic drift with Russia_Afanasievo than with Yamnaya and Groups I, II and III share more genetic drift with Poland_CW than with Russian_Afanasievo (Table S14 & Fig. S20). This pattern was also mirrored by the f2-statistics. To test for structuring in our sample set we performed multiple f4-statistics of a form f4(O, X; A, B) where O is the outgroup (Yoruba), X represent our test Eneolithic individuals divided into groups I-IV, and A & B represent populations tested for admixture. First, we tested for mutual relations between Polish Eneolithic groups from this study. While most of the results were statistically insignificant, we observed that group II was closer to group I & IV to the exclusion of group III (Z > |2|) confirming that Pełczyska would be a distinct population group. We observed that the significant f4 statistics were largely consistent with the grouping pattern on PCA (Table S16). When tested with other published European Neolithic populations we observed similar pattern in Late Eneolithic and Final Eneolithic populations, but not earlier ones, e.g. Globular Amphora. Groups I-IV are genetically closer to Russia_Afanasievo than to Yamnaya individuals (Z > |2.9|) and are also closer to Russia_Afanasievo than to each other (Z > |2.9|). Even when we compare two individuals from the same group, same chronology and same site with Russian Afanasievo with f4-statistics they share significant more genetic drift with Russian Afanasievo than with each other. These results indicate that there might be a bias in f3- and f4-statistics towards Russian Afanasievo. We do not observe this bias in the f2-statistics where individuals within groups are closer to each other than to Russian Afanasievo as expected. Due to low sample size of Afanasievo group (n = 5), which was further reduced by removing RISE507, likely the same as RISE50811 the observed affinity to the Russian Afanasievo should be interpreted with caution. To further investigate our observations and trace any bias that might result from the way reference data was generated, we perform the same f4-statistics calculation with division of Yamnaya dataset into whole-genome sequenced dataset (WGS) and enriched dataset (CP), we only trust the results of F4 stats using WGS Yamnaya data. We find that we still observe similar results to those obtained while using mixed reference dataset albeit with more similarities within WGS generated dataset (Table S16). Selected f4-statistics results are listed in Table S16. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 4, 2020 8:06:53 GMT

Kinship analyses (READ)

In order to check for kinship relations between individuals, we used Relationship Estimation from Ancient DNA (READ) between all pairs of individuals tested40 (Table S12). We identified two pairs of first-degree relatives in Święte (between the male pcw040 and boy pcv041 as well as the female pcw061 and the female pcw062), and a pair of second-degree relatives in Chłopice (the children in pcw211 and pcw212) (Tables S6). In further population based statistical analyses we exclude the individuals with lower coverage genomes from each related pair (i.e. pcw041, pcw062 and pcw212).

Pairwise Nucleotide Diversity

We used pairwise nucleotide diversity to test for differentiation between pairs of individuals, groupings (pcw040/pcw070, pcw260/pcw280 and pcw361/pcw362 representative of Groups I, III and IV respectively) and compared the values with diversity estimated in between pairs of individuals representing various Neolithic cultural groups (Figs. 4, S2). On individual level, we found that pairwise nucleotide diversity is in line with results from READ. In other words, we pickup closer relations between three pairs of individuals which were also found to be related according to READ analyses (pcw04/pcw041, pcw061/pcw062 and pce211/pcw212. On group level, we discovered that nucleotide diversity is similar between the groups and is on par with diversity found in other Eneolithic cultures (Fig. 4B). We do not include Group II as it consists of individual from different sites and could result in artificially inflated diversity estimates.

Functional SNPs

Finally, we selected the seven individuals with best genome coverage (pcw040, pcw061, pcw070, pcw211, pcw361 and pcw362), to test a number of functional SNPs, especially those associated with lactase persistence, eye and hair colour and a number of traits associated with Asian ancestry (Table S17). None of the individuals was a carrier of Asian ancestry alleles nor was any of the individuals lactose tolerant (Table S17). For those individuals who had enough coverage at pigmentation associated SNPs allowing for HirisPlex prediction, they were predicated to have been brown-eyed and dark (brown or black) haired (Table S18).

Grouping individuals according to their provenance (Sr isotopes)

Local and nonlocal individuals

According to 87Sr/86Sr values some of individuals buried at sites in the Rzeszów Foothills are non-locals with signatures below 0.710341 (Fig. 2B). While the dietary patterns of those individuals are consistent with CWC background, the archaeological and isotopic data indicate that their place of provenience (e.g. where they spent their childhood) could have been partly the Sokal Ridge or Ukraine. Using these data, and to test possible relations between the groupings of individuals we performed FST analyses using popstats42 between: A) the four groups as used for analyses in this paper (Groups I-IV); B) new grouping of four in which individuals from the Rzeszów Foothills were divided into local and non-local individuals, and where the latter were combined with individuals buried at sites in the Sokal Ridge (Group Ia, Group II-III and Group IVa); C) finally, we repeated the analyses by dividing the whole dataset into five groups (Group Ia, Group II-V), where group V consisted only of non-local individuals from the Rzeszów Foothills. We tested all possible groupings using SNP panels merged both with Human Origins and 1000 Genomes Project (Fig. S19). We find that inclusion of non-local individuals from Rzeszów Foothills in Group I makes the distance between that and the other groups lesser (Fig. S19A) than when the individuals are included in the alternative Group IVa (Fig. S19B). The general pattern of genetic distance remains the same and the results are reproducible between the two reference datasets used (Human Origins and 1000 Genome Project). When the dataset was divided into five groups (with individuals from Rzeszów Foothills divided into local and non-local group) we indeed observed that non-local individuals from Rzeszów Foothills are closest to individuals from the Sokal Ridge and both present very similar patterns in relation to other groups (Fig. S19C). However, since we detect no evidence of Group V constituting a uniform well-defined subgroup based on nucleotide diversity tests (Fig. S18) we find that grouping A, based on geography and archaeological context is most relevant for downstream genetic analyses and is thus used across different analyses.

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 5, 2020 6:00:57 GMT

Discussion

All individuals studied here are associated to burials of the CWC and BBC complexes. Based on the geographic location and the strontium isotope analysis we identified four different territorial sub groups, and based on the genetics we identified at least two different groups within our sample set. The mtDNA and the Y-chromosome data provide a slightly different picture of the genetic variation in the region contrasting earlier studies of individuals from corresponding archaeological contexts from other regions of Central Europe. In contrast to observations by Juras et al.12 we did not find mitochondrial lineages specifically linked to Yamnaya pastoralists, instead most of mtDNA lineages found in our sample may be associated with European Neolithic farming groups as is the case for the Western Corded Ware sample in the earlier study12. Our results would indicate a stronger continuity with earlier Neolithic populations than previously observed. In other words, our study detected traces of an evident “incorporation” of local individuals into the migrating groups. However, the funerary rituals seem to have been affected in limited extent as the burials exhibit the typical CWC pattern in all cases examined. The Y chromosome haplogroup lineage R1b-M269 or R-L11 are characteristic of Yamnaya and Bell Beaker individuals5,10 and they were particularly widespread throughout Eurasia in the Bronze Age and thereafter38. Curiously, the haplogroup is uncommon among other published Corded Ware Complex individuals from Europe (Germany, Poland, Bohemia, Estonia, Lithuania)6 and is associated with the later Bell Beaker communities5. We see the inclusion of the Yamnaya genetic signals but again in a different manner than what has been shown in adjacent regions. These results indicate a higher level of CWC continuity with earlier Neolithic individuals than those previously studied. The result also shows that the CWC groups exhibit an influence of the Steppe world, i.e. in the individuals with specific Y chromosome. Later the influence of the BBC communities was stronger.

The PCA revealed that despite geographical proximity there is a distinct genetic separation between CWC and BBC individuals from southern Poland. The genetic variation of CWC individuals from southern Poland overlaps with the majority of previously published CWC individuals from Germany while the eight published CWC individuals from the Polish lowland10,11 more closely resemble BBC individuals (Fig. S21). This fact is not unexpected if we consider the CWC communities in Polish lowlands as representatives of north-western parts of the CWC world called as the Single-Grave culture (see supplementary information). The genetic variation of BBC individuals from south-eastern Poland overlaps with the broad variation of BBC individuals from Central Europe (Bohemia, Moravia, Germany, south-western Poland and Hungary) (Fig. S22) which corresponds well with archaeological data. The results are in line with Admixture analyses. To determine whether the structuring can be detected on even more regional level we divided our sample into regional subgroups to test their relations.

According to f4-statistics on individual level CWC individuals from south-eastern Poland are equally different to published CWC and Yamnaya individuals, while the three Pełczyska individuals tend to select German, Estonian, Lithuanian and Polish western CWC to the exclusion of Yamnaya (Table S16). This however is not the case for CWC individuals from the Kuyavia region published by Fernandes11. CWC (but not BBC) from south-eastern Poland tends to pick Yamnaya over CWC from Kuyavia region. Our results emphasize the different impacts the Yamnaya migration event had on different populations across Europe, i.e. the genetic legacy that the Yamnaya process left varies greatly between regions and cultures.

We obtained statistically significant values for group II being closer to group I & IV to the exclusion of group III confirming that BBC Pełczyska are a distinct population group. This suggests structuring not only within the Eneolithic in southern Poland but also between groups representing the same (Archaeological) cultural horizon. Compared to the Early and Middle Neolithic samples it seems that the CWC groups I, II and IV are equally distant from the Yamnaya pastoralists and from most of the earlier published Corded Ware groups from Estonia, Germany, Lithuania and central Poland (Table S16). The south-eastern Polish CWC individuals are significantly more closely related to Yamnaya than to CWC individuals from the Polish lowland supporting the differentiation between various CWC groups from Central Europe. This is in coincidence with archaeological finds that show differences between lowlands and uplands materials of CWC23. Bell Beaker individuals from Pełczyska mostly favour German, Polish (lowland) and Estonian CWC as well as German and Czech Bell Beaker populations over Steppe ancestors (Table S16). Interestingly, in contrast to CWC individuals from south-eastern Poland (Group I, II and IV), they share significantly closer affinity to Neolithic Iberian, Italian, Hungarian, Swedish, Polish TRB and Brześć Kujawski group populations (and nonsignificant but positive affinity to Polish Globular Amphora) than Yamnaya, pointing to possible continuity between this group and earlier populations. The genetic specificity of the population associated with this process shows similarity to the features of the BBC complex in Central Europe dated ca. 150-200 years later5.

Building on the idea that the CWC complex identity is founded on the type of burial rituals performed, the study of graves and the double burials in particular can be illuminating for interpretations of the local social structures of the CWC groups regarding possible kinship structures. Positive results were obtained from 3 double graves, all containing individuals of the same sex. Kinship was observed in the graves from Chłopice grave 11 (pcw211 and pcw212) and from Święte, grave 408 (pcw061 and pcw062). The former burial represented a second-degree kinship while the latter was a first degree one. The two young boys buried in the double grave from Łubcze (pcw361 and pcw362) were not closely related according our READ analysis. However, their similar Y chromosome haplogroup (Haplogroup R1b1a1a2a1a) leaves room for a possible shared ancestry on the male linage. In Chłopice both young females died and were buried at the same time but the cause of their death could not be established. Skeletons from Łubcze were too badly preserved to provide information on time or cause of death. Interestingly in Święte (grave 408), the younger female (pcw061) probably had died earlier than the older one (pcw062) as her remains probably were exhumed from another place and added to the grave with the older female. The niche construction made “revisits” and secondary depositions possible, however this practice was part of an uncommon funeral rite in which the kinship between the two females might have had relevance. Interestingly, these closely related females spent their childhood in different places as according to strontium isotopes analysis pcw061 was a non-local and pcw62 – a local individual in the area. The observations are particularly surprising and significant considering the CWC burial customs and also social organisation. They show that in some cases close relatives were buried together in spite of different time of death. Closely related individuals were also found in graves 40 A (pcw040) and 43 (pcw041) in Święte, although not placed in a double grave they had been placed in burials in close proximity of each other. Both individuals were non-locals. The first-degree kinship identified here most likely is the father and his son, as they both have the same radiocarbon date. The close proximity of the graves indicate that kinship was an important part of the society and may have been manifested even in the funeral customs of the Corded Ware Complex communities.

Conclusion

Social processes in prehistory are hard to identify let alone interpret. Using ancient DNA and genomic analysis we can detect several levels of structuring and population dynamics within the CWC complex as well as between the CWC and BBC cultures present in Eneolithic south-eastern Poland. By evaluating the admixture between groups, the impact of earlier known demographic events like the Steppe expansions can be detected in our CWC individuals. Not surprisingly we also discover strong connections to the population in Central Germany and the CWC subpopulation living on the German lowlands. These ties are not new but they might indicate an interesting southern affiliation that has not been as clear in other previously studied samples from Poland. Furthermore, we detect less association between CWC groups from the Kuyavia region and southern Poland revealing fine scale routes of the spread of CWC traditions. The most unusual signal identified is the one between the CWC and the Afanasievo complex. This genetic incorporation from a Steppe population further east than the Yamnaya culture, is novel for these parts and suggests a CWC population structure and history more complex than previously thought. Although, our results should be treated with caution due to not just low number of samples, but the appearance of the same signal in individuals that predate steppe expansions, and are geographically more widespread. Our findings are in alignment with recent archaeological reviews suggesting lesser impact of Yamnaya event than estimated in earlier genomic studies (e.g.16,17). The CWC ancestry exhibits links both to common mtDNA linages of the initial Neolithic but also to those assimilating and replaced by the Yamnaya pastoralists. Moving further forward in time we detect genetic reminiscence of south-eastern CWC in BBC gene pool. This region was an important social area in the 3rd Millennium BCE, a true prehistoric melting pot of human groups with different origin, which may have witnessed emergence of typical BBC genomics almost 200 years earlier than in other parts of Europe5.

By using strontium isotopes, we can detect locals and non-locals in our material, which can shed light on how different subgroups within the CWC interacted. Using these characterisations as a foundation allows for deeper look into kinship amongst the buried individuals. The identification of three different types of kinship amongst the individuals studied and especially in the context of an unusual burial customs expands our understanding of rituals and traditions underlying the social structures of the CWC complex.

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 21, 2021 19:17:56 GMT

In 2015 Massive migration from the steppe In 2015 Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe and Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia were published. These two papers were game-changers. They established that the Yamnaya pastoralists of the Pontic steppe contributed a substantial proportion of ancestry to modern Europeans (later, the same was found to be the case in Indians and other Asians). As I’ve been reading and thinking about the expansion of Indo-Europeans ~3000 BC for my Substack series on the steppe, I have come to the conclusion that the populations sampled in these two papers were actually marginal to the primary expansion. The first thing to note is that the Yamnaya samples were R1b, but of a haplogroup distinctive from that of the R1b common in Western Europe, and brought by the Bell Beakers. The Yamnaya R1b is the same as that in the Afanesievo culture of western Mongolia though. The early Corded Ware tended to be R1a. How to resolve this issue? On my podcast about Indo-Europeans with David Anthony, he posits that the elite during the early period was R1b, but that later on R1a (and Bell Beaker R1b) came to the fore due to social convulsions. Perhaps. I think the other option, that there’s unsampled paternal diversity, is more plausible. I labeled where the 2015 Yamnaya were sampled from. It seems like they’re on the eastern end of the Yamnaya range. Anthony in The Horse, The Wheel, and Language, seems to lean toward the position that these eastern Yamnaya were culturally more significant than the less nomadic western Yamnaya. That’s fine, but I think it was the western Yamnaya that were the precursors to the Bell Beaker and Corded Ware. In my conversation with Nick Patterson he mentions that the Reich lab has detected Corded Ware who descend from the Yamnaya samples genealogically. How to square this with what I’m saying above? The people of the Yamnaya horizon were patrilineal and exogamous. If Corded Ware men took Neolithic wives, they almost certainly took Yamnaya wives. The western and eastern Yamnaya may have had different paternal lineages, and even been different ethnolinguistically, but still shared similar gods and folkways so that intermarriage occurred. Their autosomal genome was very similar because exchanging wives across these patrilineal kindreds was common and prevent whole-genome distinctiveness from building up. It needs to be noted that it turns out direct descendants of the Yamnaya R1b variant are present in Eastern Europe and the steppe to this day. A Russian group has found Yamnaya R1b in Crimean Tatars, and this lineage is also found in Chuvash: labs.icb.ufmg.br/lbem/pdf/Balanovsky2017HGlowlandAsia.pdf. Basically, the eastern Yamnaya ancestry has been sloshing around the steppe for thousands of years. After 2000 BC they were absorbed into Indo-Iranians, but their far eastern outliers, the Afanesievo maintained some cultural continuity in the form of the Tocharian languages. Finally, an issue in regards to time depth. The R1a division between Asian and European variants seems to date to 3500 BC. The paper above suggests that the division between Yamnaya R1b and Bell Beaker R1b dates to 4000 BC. The Yamnaya horizon people underwent a cultural revolution in the century or so prior to 3000 BC. But, they have differentiated already. On Clubhouse, I was talking to Jack V. of the Ancient Greece Decoded podcast, and he has a hard time believing that Indo-European diversified around 3000 BC. He says he can already read and understand Mycenanaen Greek from 1500 BC. I put “Yamnaya”, “Corded Ware” and “Bell Beakers” in quotes. This isn’t what they called themselves. We’ll never know their ethnolinguistic divisions. They were probably part of a broad array of related peoples, more united by lifestyle and religion than language. Note: the main issue I wonder about is the new samples that the Reich lab has and what they know. |

|