Post by Admin on Aug 16, 2023 13:12:38 GMT

Paternal kinship structure among the Bronze Age collective burials

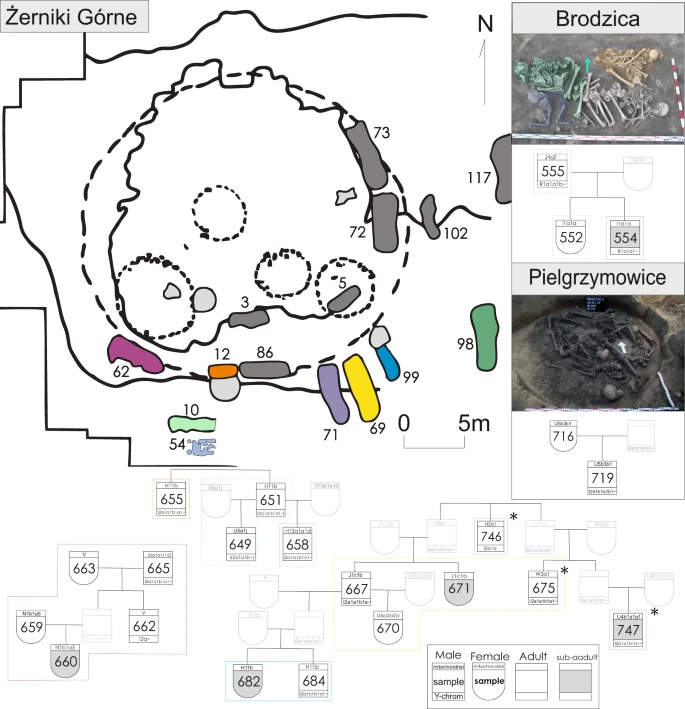

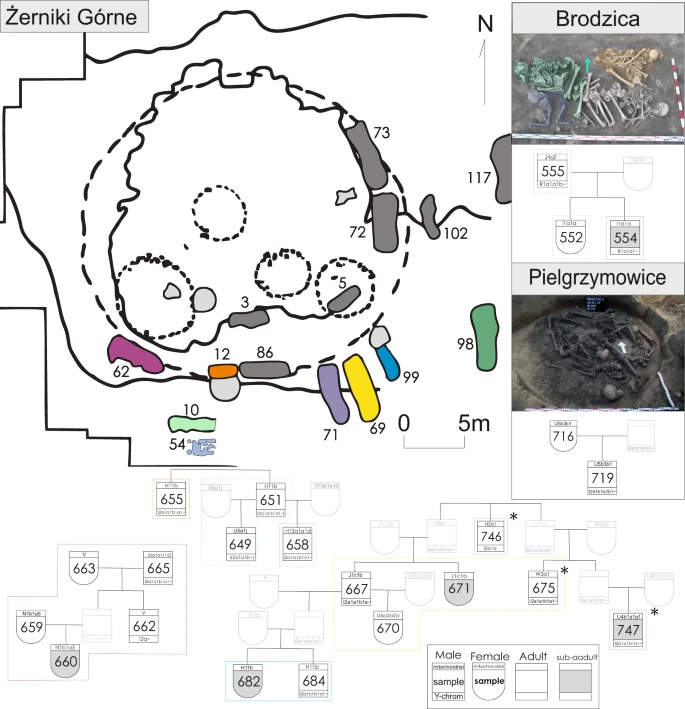

The Trzciniec Cultural Circle stands out from the other Bronze Age populations in East-Central Europe due to the high number of TC and KC-associated individuals buried in collective burials. In this study, we analysed 62 individuals from 12 archaeological sites, 52 of which were buried within structures containing remains of at least two people. In addition, as in the case of two individuals from the Dacharzów site, single graves were often in close proximity to collective burials; for example, beneath the burial mounds constructed over them30. Our data clearly show that MBA collective burials associated with the TCC contained numerous genetically related individuals, with multiple first- and second-degree kinships found within those structures (Supplementary Fig. 5). The largest number of close relationships was detected among individuals from the Żerniki Górne cemetery, which displayed the best overall aDNA preservation. Out of 28 analysed individuals interred in 9 structures, 17 individuals were found to belong to kin groups that, in some cases, had reconstructed pedigrees spanning at least 4 generations (Fig. 3). Interestingly, direct genetic kinship was also found between individuals buried in different, although adjacent, burial chambers. This shows that not only did the graves themselves represent kin groups within the population, but also that the spatial relations of graves within the cemetery represented kin relations. The prevalence of close kinship among adult male descendants compared to adult females suggests that patrilocality was the dominant marriage arrangement. This notion is further supported by higher mitochondrial diversity compared to Y-DNA diversity and larger average genetic distances between females than males. The latter is supported by D statistics that showed that males displayed greater tendency to form a clade with other Żerniki Górne individuals over the general TCC-associated population (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Data 10).

Fig. 3: The kinship structure of the Middle Bronze Age populations from East-Central Europe.

The proposed pedigrees of detected kin groups from Bronze Age cemeteries associated with the Trzciniec culture, asterisk (*) marks instances where more than one interpretation of the detected kinship is possible. The colours correspond to either the collective burials on the plan of the site in which the individuals were interred (in the case of Żerniki Górne) or the skeletal remains within collective burials. The burial photographs were reprinted with permission from Wiley from Juras, A. et al. Mitochondrial genomes from Bronze Age Poland reveal genetic continuity from the Late Neolithic and additional genetic affinities with the steppe populations. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 172, 176–188 (2020); © 2020 Wiley Periodicals, Inc All Rights Reserved.

However, not all analysed individuals within the same collective grave were genetically related. This finding could reflect the inability to sample all individuals or the inability to characterise them due to insufficient DNA preservation. Moreover, those without detectable kinship in the cemetery were mostly females (2 males and 9 females without detectable kin at Żerniki Górne), which further supports the notion of patrilocality. In some cases, such as Pielgrzymowice grave no. 9, the burial pit/chamber was used for an extended period43 and possibly spanning multiple generations; therefore, detecting multiple first- and second-degree kinships was less likely. That said, two out of five analysed individuals shared first-degree kinship and were likely a mother and her adult son. The collective grave at the Brodzica site seems to contain the remains of a nuclear family, and a sufficient amount of data was available for three out of the four individuals, all of whom were related. These individuals most likely represent a father with his two children. The fourth individual, interpreted as an adult women (although the remains did not yield enough nuclear data for kinship analysis), was found to belong to the same mitochondrial haplogroup as the two children28 and thus could potentially be their mother or an additional sibling. The MBA population associated with the TC appeared to be slightly less diverse than its EBA predecessors, according to within-group pairwise f3 statistics used for diversity estimation. This result was not driven by sites with multiple related individuals, as a similar f3 distances distribution was found in pairs of individuals from different sites (Supplementary Fig. 4C).

The idea that collective burials represent patrilineal kin groups is in accordance with previous observations of earlier Neolithic populations in Europe31,33,34,35. The prevalence of collective kin-based burials was interrupted by the arrival of steppe pastoralists in the turn of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, leading to the development of more individualised societies, such as those associated with the BBC and CWC. The practice of collective burials never disappeared completely as collective burials occurred throughout the EBA30; these graves have been shown to contain the remains of kin groups44. We identified one such example at the Hrebenne cemetery and another possibly at the Zubowice site (although the low single-nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] overlap makes this estimation uncertain); both of these collective graves were associated with the MC. The scale of this phenomenon in the TC is, however, much more similar to what was present in Neolithic societies and could be interpreted as a proof of the re-emergence of older traditions.

Patrilocal social structure and male-dominated migrations have been linked with populations and events associated with steppe pastoralists and their descendants15,45,46. Hunter-gatherer societies, on the other hand, are commonly thought to have been much more fluid in their postmarital residence preferences, with the majority of modern and historic hunter-gatherer groups displaying bilateral practices47. Due to the scarcity of samples, we could not assess the postmarital residence preferred by ancient European hunter-gatherers. On the other hand, recent data obtained on Middle Neolithic farmers from Western and Central Europe show that collective burials in these populations usually comprised related individuals of patrilocal descent31,33,48, supporting the notion that those populations or their descendants also played a role in the events that resulted in the genetic shift in the MBA.

The results presented here indicate that EBA people in East-Central Europe buried in the MC, IC and SC contexts were most likely the direct descendants of preceding populations associated with the CWC. In addition, the MBA populations were dominated by patrilocal lineages of apparent hunter-gatherer origin, practising burial customs that, while displaying some elements associated with steppe pastoralists, were most analogous to those practised in the Middle and Late Neolithic cultures, predating the arrival of steppe pastoralists into Central Europe. We conclude that after the introduction of steppe ancestry into European populations, hunter-gatherers and farmers remained genetically distinct in some regions and influenced later demographic and cultural processes, as seen in the genetic composition of MBA populations.

The Trzciniec Cultural Circle stands out from the other Bronze Age populations in East-Central Europe due to the high number of TC and KC-associated individuals buried in collective burials. In this study, we analysed 62 individuals from 12 archaeological sites, 52 of which were buried within structures containing remains of at least two people. In addition, as in the case of two individuals from the Dacharzów site, single graves were often in close proximity to collective burials; for example, beneath the burial mounds constructed over them30. Our data clearly show that MBA collective burials associated with the TCC contained numerous genetically related individuals, with multiple first- and second-degree kinships found within those structures (Supplementary Fig. 5). The largest number of close relationships was detected among individuals from the Żerniki Górne cemetery, which displayed the best overall aDNA preservation. Out of 28 analysed individuals interred in 9 structures, 17 individuals were found to belong to kin groups that, in some cases, had reconstructed pedigrees spanning at least 4 generations (Fig. 3). Interestingly, direct genetic kinship was also found between individuals buried in different, although adjacent, burial chambers. This shows that not only did the graves themselves represent kin groups within the population, but also that the spatial relations of graves within the cemetery represented kin relations. The prevalence of close kinship among adult male descendants compared to adult females suggests that patrilocality was the dominant marriage arrangement. This notion is further supported by higher mitochondrial diversity compared to Y-DNA diversity and larger average genetic distances between females than males. The latter is supported by D statistics that showed that males displayed greater tendency to form a clade with other Żerniki Górne individuals over the general TCC-associated population (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Data 10).

Fig. 3: The kinship structure of the Middle Bronze Age populations from East-Central Europe.

The proposed pedigrees of detected kin groups from Bronze Age cemeteries associated with the Trzciniec culture, asterisk (*) marks instances where more than one interpretation of the detected kinship is possible. The colours correspond to either the collective burials on the plan of the site in which the individuals were interred (in the case of Żerniki Górne) or the skeletal remains within collective burials. The burial photographs were reprinted with permission from Wiley from Juras, A. et al. Mitochondrial genomes from Bronze Age Poland reveal genetic continuity from the Late Neolithic and additional genetic affinities with the steppe populations. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 172, 176–188 (2020); © 2020 Wiley Periodicals, Inc All Rights Reserved.

However, not all analysed individuals within the same collective grave were genetically related. This finding could reflect the inability to sample all individuals or the inability to characterise them due to insufficient DNA preservation. Moreover, those without detectable kinship in the cemetery were mostly females (2 males and 9 females without detectable kin at Żerniki Górne), which further supports the notion of patrilocality. In some cases, such as Pielgrzymowice grave no. 9, the burial pit/chamber was used for an extended period43 and possibly spanning multiple generations; therefore, detecting multiple first- and second-degree kinships was less likely. That said, two out of five analysed individuals shared first-degree kinship and were likely a mother and her adult son. The collective grave at the Brodzica site seems to contain the remains of a nuclear family, and a sufficient amount of data was available for three out of the four individuals, all of whom were related. These individuals most likely represent a father with his two children. The fourth individual, interpreted as an adult women (although the remains did not yield enough nuclear data for kinship analysis), was found to belong to the same mitochondrial haplogroup as the two children28 and thus could potentially be their mother or an additional sibling. The MBA population associated with the TC appeared to be slightly less diverse than its EBA predecessors, according to within-group pairwise f3 statistics used for diversity estimation. This result was not driven by sites with multiple related individuals, as a similar f3 distances distribution was found in pairs of individuals from different sites (Supplementary Fig. 4C).

The idea that collective burials represent patrilineal kin groups is in accordance with previous observations of earlier Neolithic populations in Europe31,33,34,35. The prevalence of collective kin-based burials was interrupted by the arrival of steppe pastoralists in the turn of the Neolithic and Bronze Age, leading to the development of more individualised societies, such as those associated with the BBC and CWC. The practice of collective burials never disappeared completely as collective burials occurred throughout the EBA30; these graves have been shown to contain the remains of kin groups44. We identified one such example at the Hrebenne cemetery and another possibly at the Zubowice site (although the low single-nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] overlap makes this estimation uncertain); both of these collective graves were associated with the MC. The scale of this phenomenon in the TC is, however, much more similar to what was present in Neolithic societies and could be interpreted as a proof of the re-emergence of older traditions.

Patrilocal social structure and male-dominated migrations have been linked with populations and events associated with steppe pastoralists and their descendants15,45,46. Hunter-gatherer societies, on the other hand, are commonly thought to have been much more fluid in their postmarital residence preferences, with the majority of modern and historic hunter-gatherer groups displaying bilateral practices47. Due to the scarcity of samples, we could not assess the postmarital residence preferred by ancient European hunter-gatherers. On the other hand, recent data obtained on Middle Neolithic farmers from Western and Central Europe show that collective burials in these populations usually comprised related individuals of patrilocal descent31,33,48, supporting the notion that those populations or their descendants also played a role in the events that resulted in the genetic shift in the MBA.

The results presented here indicate that EBA people in East-Central Europe buried in the MC, IC and SC contexts were most likely the direct descendants of preceding populations associated with the CWC. In addition, the MBA populations were dominated by patrilocal lineages of apparent hunter-gatherer origin, practising burial customs that, while displaying some elements associated with steppe pastoralists, were most analogous to those practised in the Middle and Late Neolithic cultures, predating the arrival of steppe pastoralists into Central Europe. We conclude that after the introduction of steppe ancestry into European populations, hunter-gatherers and farmers remained genetically distinct in some regions and influenced later demographic and cultural processes, as seen in the genetic composition of MBA populations.