|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 12, 2019 23:27:58 GMT

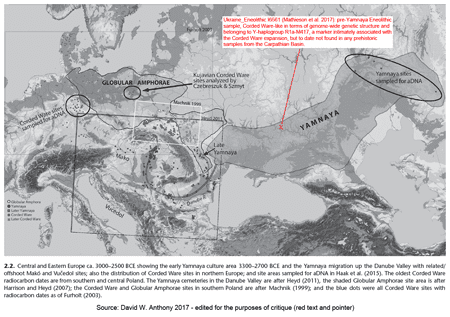

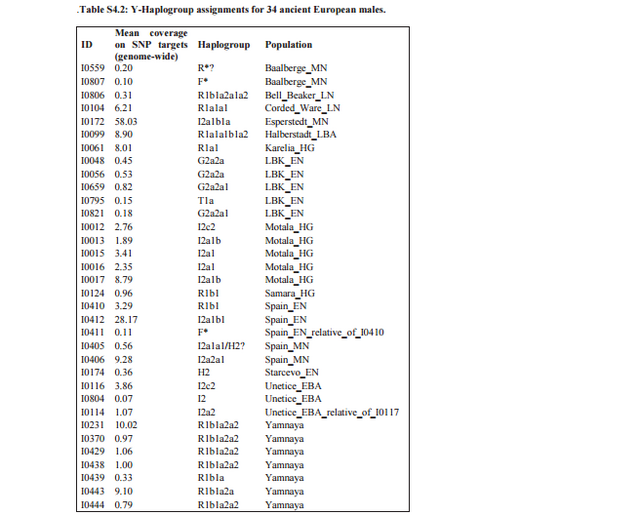

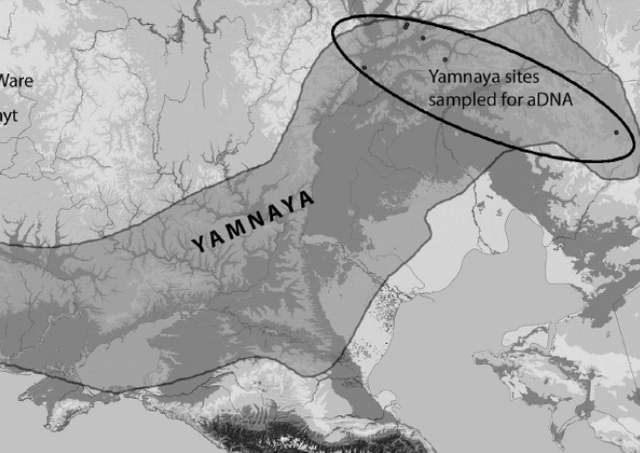

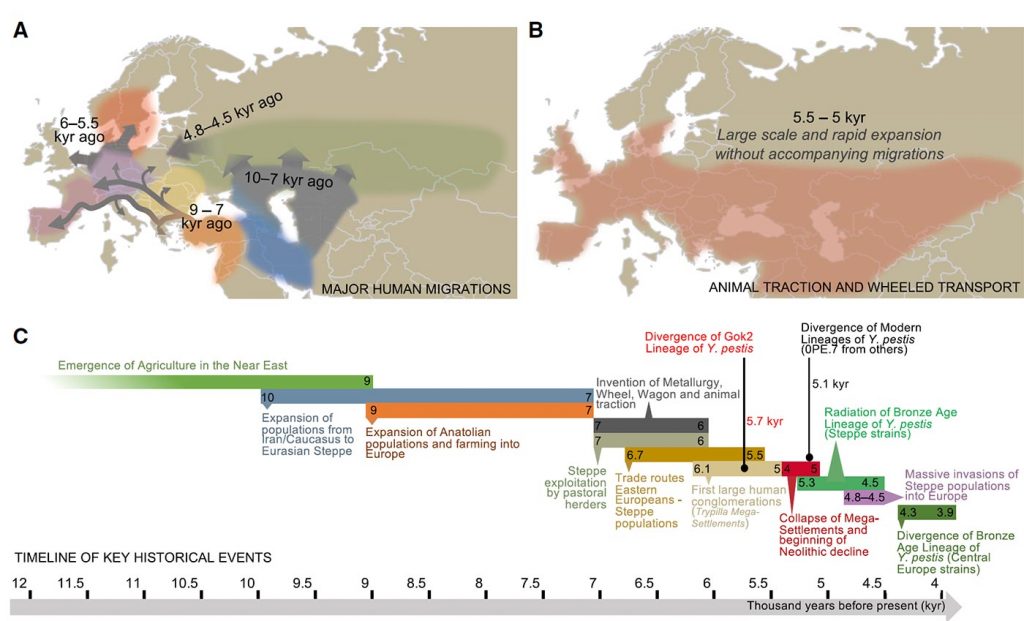

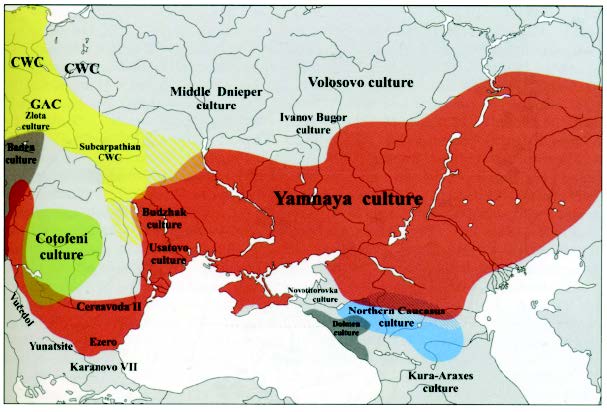

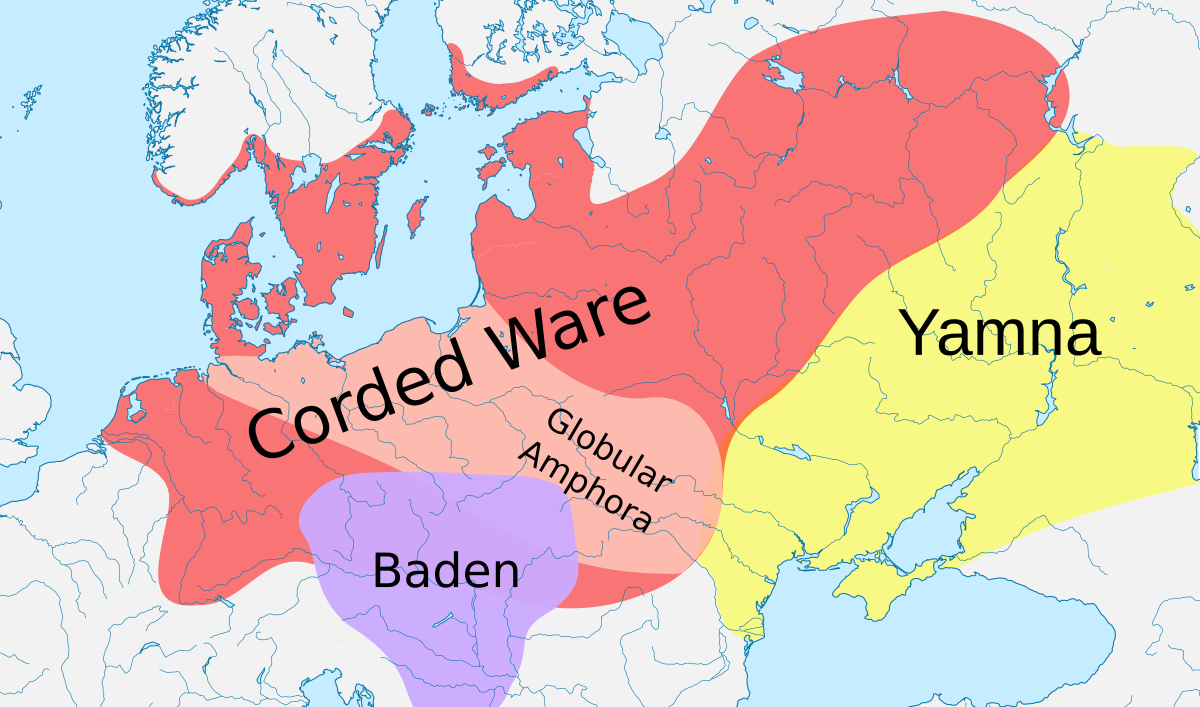

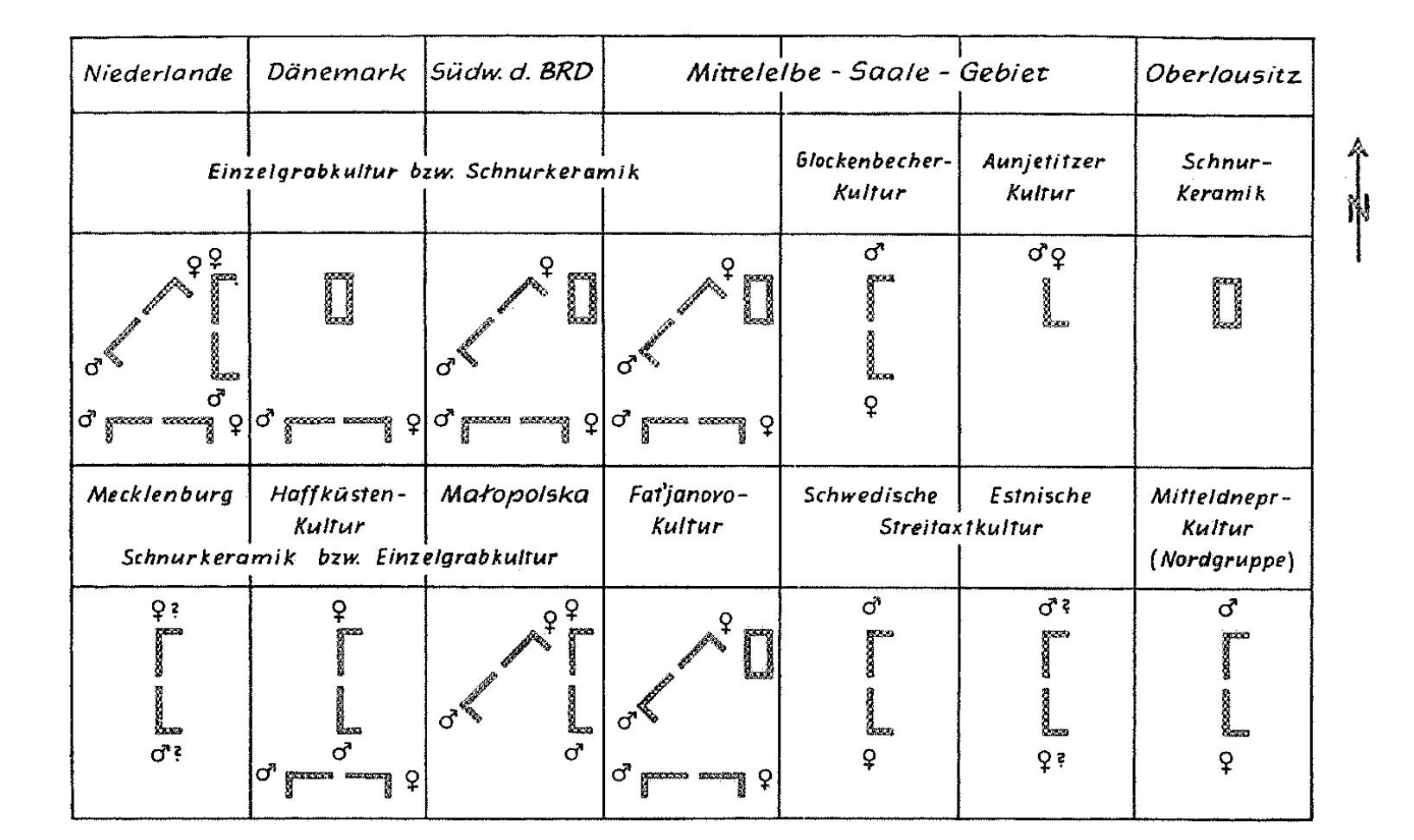

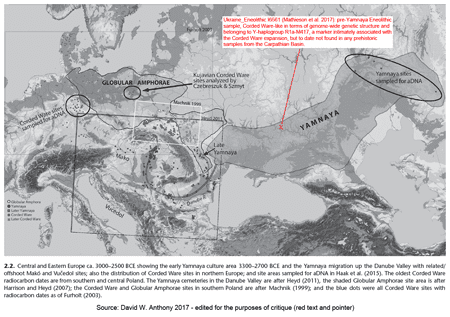

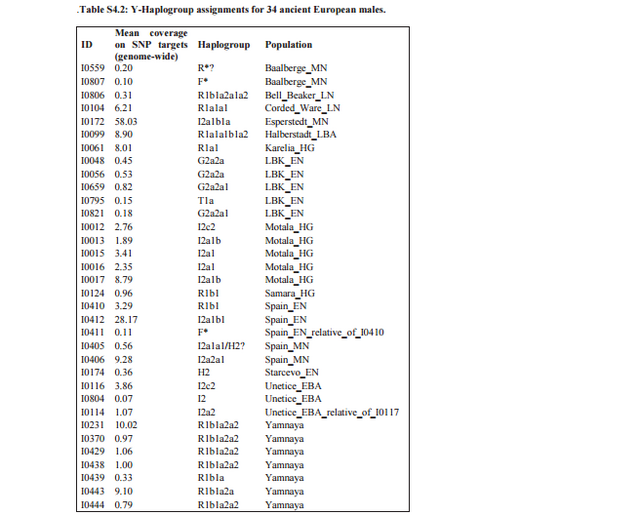

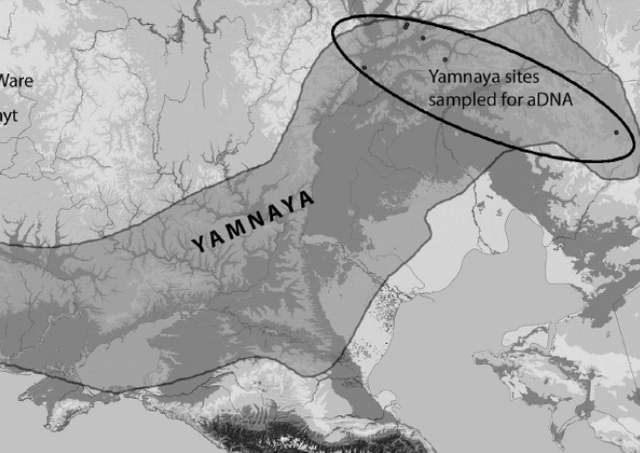

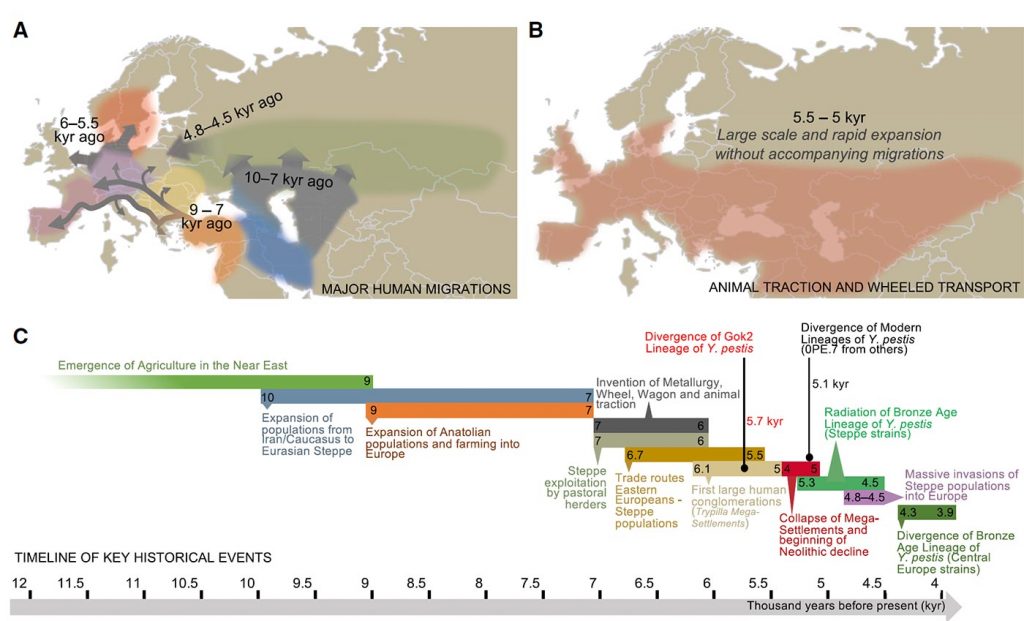

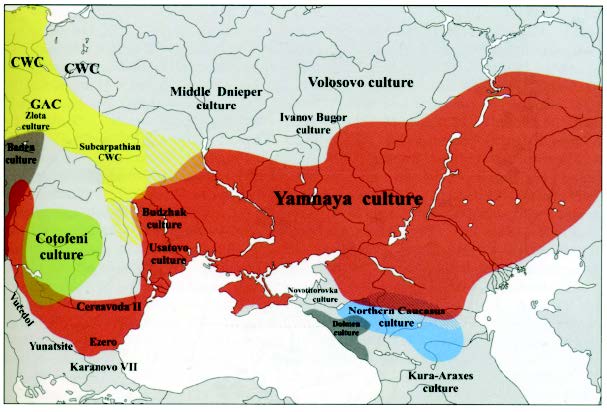

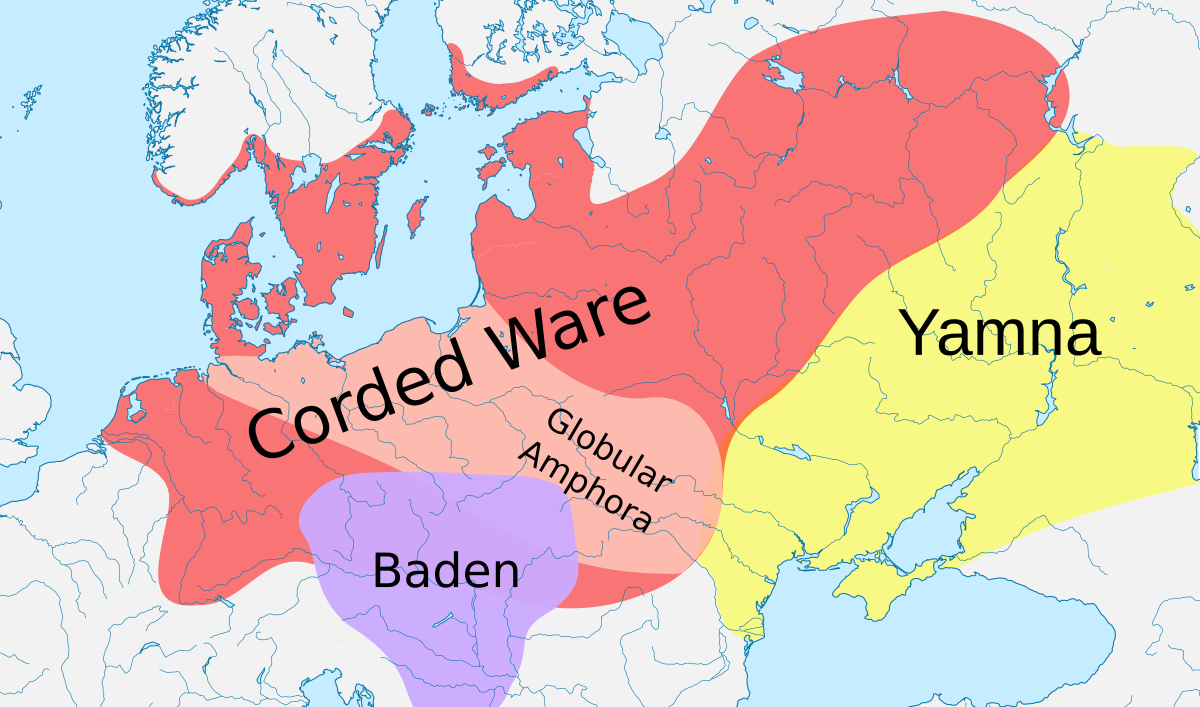

A Yamnaya migration from the steppes up the Danube valley as far as Hungary was already accepted by many archaeologists (Fig. 2.2). Hundreds of Yamnaya-type kurgans and dozens of cemeteries have been recognized by archaeologists in the lower Danube valley, in Bulgaria and Romania; and in the middle Danube valley, in eastern Hungary, with radiocarbon dates that began about 3000–2800 BCE and extended to about 2700–2600 BCE (Ecsedy 1979; Sherratt 1986; Boyadziev 1995; Harrison and Heyd 2007; Heyd 2012; Frînculeasa et al. 2015). The migration stream that created these intrusive cemeteries now can be seen to have continued from eastern Hungary across the Carpathians into southern Poland, where the earliest material traits of the Corded Ware horizon appeared (Furholt 2003). Corded Ware sites appeared in Denmark by 2800–2700 BCE, probably within 100–200 years after the first Yamnaya migrants entered the lower Danube valley. This surprisingly rapid migration introduced genetic traits such as the R1a and R1b Y-chromosome haplogroups and a substantial element of ANE (Ancient North Eurasian) ancestry that remain characteristic of most northern and western Europeans today.  2.2. Central and Eastern Europe ca. 3000–2500 BCE showing the early Yamnaya culture area 3300–2700 BCE and the Yamnaya migration up the Danube Valley The oldest radiocarbon dates from Corded Ware sites occur in southern Poland (upper Vistula) and north-central Poland (Kujavia), and this was seen as the region where the early networking of amphorae styles from Globular Amphorae and axe types from Scandinavia began. The genetic evidence shows a somewhat different picture: the Corded Ware people were largely immigrants whose ancestors came from the steppes (probably immediately from eastern Hungary), but they quickly adopted local material traits in amphorae and axe types that obscured their foreign origins. Middle Neolithic northern European populations composed of admixed WHG/EEF survived but were largely excluded from Corded Ware cemeteries, and from marriage into the Corded Ware population. Even centuries after the initial migration the Corded Ware population at Esperstedt, dated 2500–2400 BCE, still exhibited 70–80% Yamnaya genes, although individual variations in the extent of local admixture were apparent. Intermarriage with the surviving local population was more frequent during the ensuing Bell Beaker period. However, the resurgence is more visible in mtDNA than in Y-DNA (Szécsényi-Nagy et al. 2015), suggesting that men of the older EEF heritage were disadvantaged more than women. Settlements were more permanent before the Corded Ware migration, and remained so among the Globular Amphorae people, who continued to create more localized site-and-cemetery groups in the same landscape with the more mobile immigrants. Afterward, during the Bell Beaker period, when local genetic ancestry rebounded and the population became more admixed, settlements again were more permanent. The Corded Ware culture introduced both a large, steppe-derived population and an unusually mobile form of pastoral economy that was a regional economic anomaly, but nevertheless survived in varying forms for centuries before the regional economic pattern was re-established. A steppe language certainly accompanied this demographic and economic shift. As we have seen above, there are good independent reasons (loans with Uralic and South Caucasian) to think that PIE was spoken in the steppes. It is likely that the steppe language introduced between 3000–2500 BCE was a late (post-Anatolian) form of PIE and survived and evolved into the later northern IE languages. The biggest surprise of the new genetic research was a genetic shift dated to the Late Neolithic in Germany, 3000–2500 BCE, when the Corded Ware horizon spread across most of northern Europe (Fig. 2.2). Childe (1950:133–38) and Gimbutas (1963) speculated that migrants from the steppe Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BCE) might have been the creators of the Corded Ware culture and carried IE languages into Europe from the steppes. Yamnaya was the first steppe culture to take advantage of both wagons (for bulk transport) and horseback riding (for rapid transport), cre-ating a new and more mobile form of pastoralism in the steppes (Anthony 2007:300ff.). But the similarities between Yamnaya and Corded Ware were rather general—single graves under mounds, weapons in the grave, promi-nent gender distinctions in graves—rather than typologically specific, leav-ing open the possibility of a diffusion of ideas rather than people. Recent scholarship suggested that Corded Ware could be regarded as an indigenous northern European development without a necessary external component (Furholt 2003, 2014). However, aDNA from Corded Ware graves provided surprisingly strong evidence supporting the steppe migration theory (Haak et al. 2015; Allentoft et al. 2015).  Four Corded Ware individuals buried at Esperstedt, Germany between 2500–2300 BCE, found in typical Corded Ware graves according to body po-sition and pottery, along with an additional Corded Ware individual buried in an atypical ritual in an older Baalberge monument at Karsdorf, exhib-ited genomes that were a mixture of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) and a previously unseen Near Eastern ancestry most similar to individuals from prehistoric northwestern Iran and the Caucasus. This EHG/Caucasus an-cestry, measured at 390k locations across the whole genome, was very dif-ferent from the local WHG, EEF, or the admixed WHG/EEF Middle Neo-lithic population in western and northern Europe. The new type was very similar to the EHG/Caucasus mixture that characterized nine Yamnaya-culture individuals from six kurgan cemeteries in the Volga-Ural steppes, dated 3200–2800 BCE (Haak et al. 2015), obtained during the Samara Valley Project (Anthony et al. 2005; Anthony et al. 2016). The tested Corded Ware individuals are modeled as having an ancestry 79% derived from Yamnaya, 4% from WHG, and 17% from EEF (Haak et al. 2015). Moreover, an in-dependent, even larger study of Corded Ware individuals from Estonia, Poland, and Germany found a similarly high average proportion of Yam-naya ancestry, in this case using as the steppe example aDNA from a group of Yamnaya graves in the North Caucasus steppes, which turned out to be very similar genetically to the Yamnaya from Samara on the middle Volga (Allentoft et al. 2015). The strength of Yamnaya ancestry in all of the tested Corded Ware people is surprising, given that many were late Corded Ware individuals, not first-generation migrants, and they lived 3000 km west of the region from which the Yamnaya aDNA was recovered. In addition, uni-parental markers also changed suddenly as mtDNA haplogroup N1a and Y haplogroup G2a, which had been very common in the EEF agricultural population, were replaced by Y haplogroups R1a and R1b and by a vari-ety of mtDNA haplogroups typical of the steppe Yamnaya population. The uniparental markers show that the migrants included both men and women from the steppes.The Corded Ware individuals were not the only ones to show strong steppe ancestry. Ten Bell Beaker individuals dated 2500–2100 BCE from five cemeteries in Germany and nine Únětice individuals dated 2100–1900 BCE from four cemeteries all showed 50–70% Yamnaya-like ancestry (Haak et al. 2015: S.I. 3), but they also showed a resurgence of ancestry from the WHG and EEF inhabitants. Again, Allentoft et al. (2015) found the same pattern in a separate sample of Bell Beaker and Únětice samples. This more admixed Bell Beaker and Únětice sample was almost indistinguishable ge-netically from many modern Europeans. After the Bell Beaker period, the genetic composition of Europe continued to the present day without an-other demographic discontinuity comparable in scale to the Late Neolithic transition. The steppe-derived languages spoken by the Yamnaya migrants between 3000–2500 BCE, arguably the post-Anatolian variety of Proto-Indo-European with the shared wheel vocabulary, also could have continued to evolve in Europe without another major break. The languages spoken by the local Middle Neolithic population must have declined with the sudden reduction in its size.  A Yamnaya migration from the steppes up the Danube valley as far as Hungary was already accepted by many archaeologists (Fig. 2.2). Hundreds of Yamnaya-type kurgans and dozens of cemeteries have been recognized by archaeologists in the lower Danube valley, in Bulgaria and Romania; and in the middle Danube valley, in eastern Hungary, with radiocarbon dates that began about 3000–2800 BCE and extended to about 2700–2600 BCE (Ecsedy 1979; Sherratt 1986; Boyadziev 1995; Harrison and Heyd 2007; Heyd 2012; Frînculeasa et al. 2015). The migration stream that created these intrusive cemeteries now can be seen to have continued from eastern Hun-gary across the Carpathians into southern Poland, where the earliest ma-terial traits of the Corded Ware horizon appeared (Furholt 2003). Corded Ware sites appeared in Denmark by 2800–2700 BCE, probably within 100–200 years after the first Yamnaya migrants entered the lower Danube valley. This surprisingly rapid migration introduced genetic traits such as the R1a and R1b Y-chromosome haplogroups and a substantial element of ANE (Ancient North Eurasian) ancestry that remain characteristic of most northern and western Europeans today.Furholt (2014) argued convincingly that many of the material traits that define the Corded Ware culture originated in different places and were gradually networked together, so that the homogeneous A phase began after the earliest phase, which exhibited more variety. This suggested to him that the Corded Ware culture evolved from diverse sources locally in north-ern Europe. The oldest radiocarbon dates from Corded Ware sites occur in southern Poland (upper Vistula) and north-central Poland (Kujavia), and this was seen as the region where the early networking of amphorae styles from Globular Amphorae and axe types from Scandinavia began. The ge-netic evidence shows a somewhat different picture: the Corded Ware people were largely immigrants whose ancestors came from the steppes (probably immediately from eastern Hungary), but they quickly adopted local mate-rial traits in amphorae and axe types that obscured their foreign origins.  Middle Neolithic northern European populations composed of admixed WHG/EEF survived but were largely excluded from Corded Ware ceme-teries, and from marriage into the Corded Ware population. Even centuries after the initial migration the Corded Ware population at Esperstedt, dated 2500–2400 BCE, still exhibited 70–80% Yamnaya genes, although individual variations in the extent of local admixture were apparent. Intermarriage with the surviving local population was more frequent during the ensuing Bell Beaker period. However, the resurgence is more visible in mtDNA than in Y-DNA (Szécsényi-Nagy et al. 2015), suggesting that men of the older EEF heritage were disadvantaged more than women. Corded Ware represented a non-local extreme both genetically and economically. A systematic comparison of animal bone, feature, and sherd counts from broadly contemporary Globular Amphorae and Corded Ware sites in Kujavia, Poland (Czebreszuk and Szmyt 2011:251–52) showed that Corded Ware sites exhibited the fewest in all three counts, suggesting greater settlement mobility. Settlements were more permanent before the Corded Ware migration, and remained so among the Globular Amphorae people, who continued to create more localized site-and-cemetery groups in the same landscape with the more mobile immigrants. Afterward, during the Bell Beaker period, when local genetic ancestry rebounded and the population became more admixed, settlements again were more per-manent. The Corded Ware culture introduced both a large, steppe-derived population and an unusually mobile form of pastoral economy that was a regional economic anomaly, but nevertheless survived in varying forms for centuries before the regional economic pattern was re-established. A steppe language certainly accompanied this demographic and economic shift. As we have seen above, there are good independent reasons (loans with Uralic and South Caucasian) to think that PIE was spoken in the steppes. It is likely that the steppe language introduced between 3000–2500 BCE was a late (post-Anatolian) form of PIE and survived and evolved into the later northern IE languages. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 13, 2019 18:08:03 GMT

With recent results from ancient DNA research showing an extensive incoming gene flow into Europe shortly after 3000 BC (Allentoft et al. 2015; Haak et al. 2015), we are finally in a position where migrations can be documented rather than debated as an element in the formation of the Corded Ware Culture. This has lifted an interpretative burden from archaeology in much the same way as did 14C dating when it was introduced. The new ‘freedom’ can instead be invested in properly theorising and interpreting local processes of migration, integration and consolidation, which represent an underdeveloped field of research. By integrating recent results from genetics, stable isotopes, archaeology and historical linguistics, this will in turn allow us to formulate better-founded models for the interaction of intruding and settled groups and the formation of a new material culture, and consequently better models for language dispersal and language change.  Re-theorising migrations The evidence from the recent studies of ancient DNA documenting human migrations into temperate Europe during the early third millennium BC can be summarised as follows: There was a widespread process of genetic admixture, leading to a reduction of Neolithic DNA in temperate Europe and the dramatic increase of a new genomic component that was only marginally present in Central Europe prior to 3000 BC (Allentoft et al. 2015; Haak et al. 2015; Cassidy et al. 2016). Although the details of this admixture event can and will be debated for years to come (Vander Linden 2016), it remains beyond question that the observed change in the gene pool must have involved the migration of people. Moreover, the apparent abruptness with which this change occurred suggests that it was a large-scale migration event, rather than a slow periodic gene flow across many centuries.  The Yamnaya people from the Pontic-Caspian steppe are the best-known proxy for this incoming gene flow. The exact source could have been another, yet unsampled, group of people, but, in that case, they must have been very closely related genetically to Yamnaya. What facilitated this major demographic event remains open to speculation, but the late fourth millennium BC was a period of widespread technological innovation, which also introduced long-distance travel. This horizon could thus have formed a prelude to the Yamnaya migrations, opening up new corridors of cultural transmission on which subsequent developments depended (Johannsen & Laursen 2010; Hansen 2011, 2014). Moreover, a decline in Neolithic activity around 3000 BC (Hinz et al. 2012; Shennan et al. 2013) could indicate a crisis in Neolithic societies, thereby allowing space for incoming migrants. In that light, the recent documentation of an early form of plague, widespread from Siberia to the Baltic in the early third millennium BC, could play a key role in explaining this genetic changeover (Rasmussen et al. 2015). These extensive demographic changes led to the formation of a new social and economic order in large parts of temperate Europe, resulting in the formation of the Corded Ware Culture. As evident from, for example, western Jutland (Andersen 1993; Kristiansen 2007), Corded Ware people burned down forests on a massive scale, thereby creating open, steppe-like grazing lands for their herds. A more gradual opening of the landscape is also found in other regions (Doppler et al. 2015), while subsistence seems to have been a variable mix of cultivation, husbandry and some hunting and gathering (Müller et al. 2009).  The Corded Ware Culture elected the battle-axe as the most prominent male symbol, and created new types of pottery. Among the Yamnaya cultures, the tradition of pottery-making was weakly developed. Being a pastoral, mobile economy, they instead employed containers made of leather, wood and bast, and woven vessels could have been used as well, just as they used mats and other lightweight materials that were easy to transport in their wagons (Shishlina 2008: 60, fig. 54). The Corded Ware Culture had widely shared similarities in burial rituals over vast distances (Furholt 2014: fig. 7), and had strong affinities to the Yamnaya burial rituals known from the steppe. The tens of thousands of small, single-grave barrows in Northern Europe were aligned in rows across the landscape, in a similar way to the practice on the steppe. They formed visible lines of communication in these vast open environments (Hübner 2005; Bourgeois 2013). The unifying element between Yamnaya and Corded Ware is the burial ritual of a single inhumation under a barrow, even though there are minor differences in grave goods and the positioning of the body. Burial rituals are among the most fundamental social institutions in any society, as they relate to the transmission of property and power at death, to cosmology and religion, and, in the case of settlements, to the way households are organised. We can therefore formulate this as an axiom: A strong relationship exists between burial ritual and social and religious institutions, because a burial is the institutionalised occasion for the transmission of property and power, and the renewal of social and economic ties (Oestigaard & Goldhahn 2006). A radical change in burial rites therefore signals a similar change in beliefs and institutions. If such a change occurs rapidly without transition it signals a transformation of society, often under strong external influence, possibly a migration (to be supported also by settlement change and economic change). This does not rule out the effects of internal contradictions, which, however, often go hand in hand with external forces of change. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 14, 2019 17:51:21 GMT

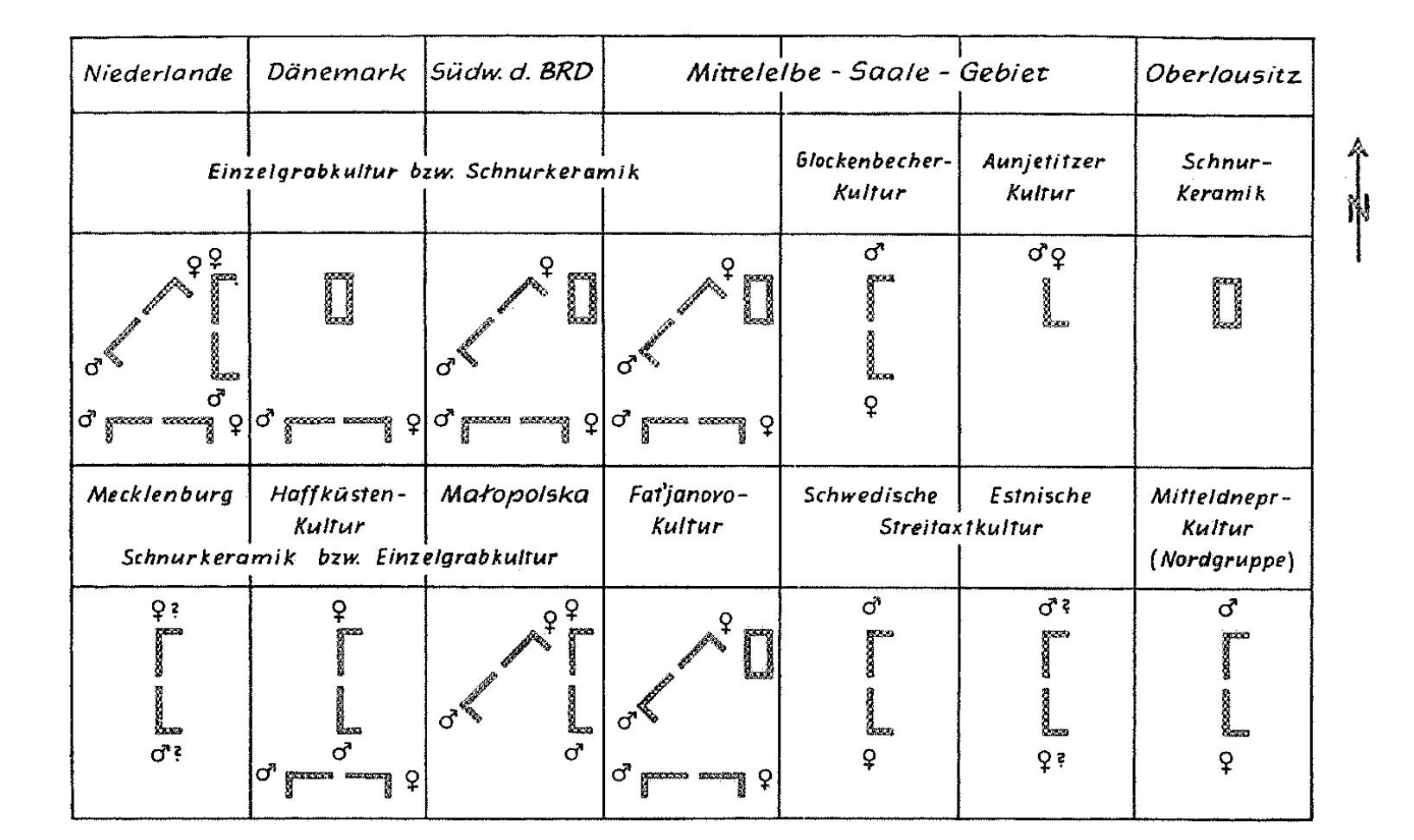

5 Correspondence analysis of amphorae from the Złota-graveyards reveals that there is no typological break between Globular Amphorae and Corded Ware Amphorae. The formation of the Yamnaya and Corded Ware Cultures Given that widespread migrations from the Caspian-Pontic steppe now constitute a key element in any plausible explanation of the Corded Ware phenomenon, we need to focus attention on how it unfolded locally in order to understand processes of demographic and cultural dominance. But we also need to understand the economic and social system of the Yamnaya culture from which it originated, and which flourished and expanded from around 3000 BC (Anthony 2007). First, it should be noted that the Yamnaya cultures of the Pontic and Caspian steppe represented the first development of a fully pastoral economy that exploited different ecological niches during small-scale seasonal movements of people and animals between summer and winter grazing. Its economy and variability has been analysed in detail by Natalia Shishlina in a classic work (Shishlina 2008). This variability is also reflected in diet (Shishlina et al. 2012). The period after 3000 BC saw a more humid climate that favoured grassland productivity, and thus the new pastoral economy experienced a rapid demographic expansion that included eastern Central Europe: Bulgaria, Hungary and Transylvania, and Northern Europe soon afterwards (Harrison & Heyd 2007; Heyd 2011; Gerling et al. 2012; Horváth et al. 2013; Kaiser & Winger 2015). Herds consisted of cattle, sheep and horse, and the mobile lifestyle within small territories was supported by the use of wagons as mobile homes. Only a few stable settlements are known, but from burial pits, we find extensive use of thick plant mats and felt covers; the same materials were probably in use for dwellings. Light-framework dwellings could easily be assembled and disassembled and transported on pack animals. The economy was based on meat and dairy products, as well as fish (reflected in high 15N values), and seeds from wild plants were collected and used in soup with meat (Schulting & Richards 2016). No agriculture is documented, but to the west, some cereal cultivation was practised (Pashkevych 2012). Extensive exchange systems linked different groups together and secured access to products outside the pastoral economy, such as metal. The healthy diet meant that life expectancy was fairly high, with many individuals living to 50–60 years old. We can also observe a selection for lactose tolerance and for height (Mathieson et al. 2015). Barrows were aligned in groups forming lines in the landscape to mark seasonal routes. Similar arrangements are found in Northern Europe, suggesting a shared perception and use of landscapes among Single Grave populations from Holland to western Jutland (Hübner 2005; Bourgeois 2013).  Secondly, we should observe that Corded Ware Cultures co-existed with late Neolithic cultures for shorter or longer periods across much of Central and Northern Europe. In Denmark, there were late Funnel Beaker communities in the Danish islands (Iversen 2015); in other parts of Northern Europe they were often in close proximity, such as the Globular Amphora Culture in Poland (Szmyt 1999). What we observe, therefore, in the archaeological record is a gradual process of acculturation and integration, which meant that after 2400 BC, the former strict cultural boundaries were gradually dissolved and a new, shared material culture appeared, represented first and foremost in Denmark by flint daggers, and in Central Europe by early Únetiče metal daggers. Bell Beaker groups had by now also emerged on the scene, introducing metallurgy, and they further complicated the mix of cultures and people. In burial rituals, however, old megalithic traditions still had an impact, as seen in a revival of stone cist burial in some regions. It was only on the advent of the Middle Bronze Age that cultural homogenisation prevailed. Thus, it took nearly 1000 years before all regions in Northern and Central Europe had adopted a shared social and cultural outlook that in all probability also included shared languages. With the help of strontium isotopic analysis and ancient DNA we can now reconstruct in some detail the social processes behind the observable archaeological changes. At the Corded Ware cemetery of Eulau, the application of strontium isotopic tracing, ancient DNA and archaeology has allowed a full reconstruction of a singular family massacre and its local background (Haak et al. 2008; Meyer et al. 2009; Muhl et al. 2010). Four multiple burials contained single families of father, mother and children in various combinations, and it could be demonstrated that the mothers were of non-local origin, most probably originating in the Harz Mountains 50–60km north of the settlement. The arrows that had killed the families confirmed this, as they belonged to another Neolithic culture: the Schönfeld, which was located in this area and practised cremation, a burial custom different to that of the Corded Ware Culture (compare Muhl et al. 2010: 44, 125). Contacts between the two are also illustrated by the occurrence of Schönfeld pottery in Corded Ware graves in the Halle-Saale region (Furholt 2003). Other Neolithic groups in the region, such as the Bernburg Culture, practised collective burials of multiple family groups, as demonstrated by genetics, again being distinctively different from the Corded Ware practice of individual burials (Meyer et al. 2012). We observe two things: that Corded Ware males practised exogamy, perhaps marriage by abduction, which provides a possible explanation for the killing. The question is: was this a unique case, or did it reflect a more widespread marriage practice, as suggested by Schönfeld pottery in Corded Ware burials?  The female diet was more similar to previous Neolithic diets, while in Corded Ware as a whole there is a shift towards higher δ15N values, suggestive of a shift in diet and/or in cultivation practices. There may be several different explanations for this shift, such as intense forms of cultivation, higher reliance on freshwater fish, or on animal versus vegetable protein, or a greater reliance on milk and milk products. The latter is supported by a widespread opening-up of landscapes in some regions for grazing animals (Andersen 1993, 1995; Doppler et al. 2015; Dietre et al. 2016). The analysis comprises 60 individuals and covers the period from the early Corded Ware to the mature and late Corded Ware; in other words, from 2900/2800–2300 BC. Among the burials from the earliest, colonising phase at Tiefbrunn, we find a multiple burial of three individuals: one older male with a hammer-headed pin of steppe type, a young adult male and a female child, around four years old. mtDNA haplogroups were different for all three, indicating that they were not related on the maternal side (Allentoft et al. 2015). Sr isotope ratios suggest that the older man was non-local, while the younger man and the child may have been locals. The skulls of all three individuals exhibited signs of severe trauma and they had probably suffered violent deaths, which again demonstrates that the newcomers were not always welcomed peacefully. There is a similar early burial from the Kujawy region in Poland, of an elderly male of non-local origin, who also had a hammer-headed pin showing steppe influence (Pospieszny et al. 2015). Analysis of ancient DNA from the Tiefbrunn multiple burial showed a high percentage of Yamnaya steppe DNA. The larger, consolidated cemeteries from Bergrheinfeld and Lauda-Königshofen are from the middle phase of the Corded Ware Culture (2600–2500 BC), and here the practice of exogamy was well established over a longer period of time. We cannot know where the non-local women were from, but as their diet looked more ‘Neolithic’, we may assume that they originated in late Neolithic cultures still residing on the higher elevations in the region. Exogamy is a clever, and perhaps necessary, policy if new migrating groups are mainly constituted by males. This is a probable scenario for an expanding pastoral economy, and is supported by archaeological data from the early horizon of the Single Grave/Corded Ware Culture in Jutland, where 90 per cent of all burials belonged to males (Hübner 2005: 632–33, fig. 454). It gains further support from later historical sources from India to the Baltic and Ireland (Falk 1986; Kershaw 2000). They describe, as a typical feature of these societies, the formation of warrior youth bands consisting of boys from 12–13 up to 18–19 years of age, when they were ready to enter the ranks of fully grown warriors. Such youthful war-bands were led by a senior male, and they were often named ‘Black Youth’ or given names of dogs and wolves as part of their initiation rituals. The nature of this institution was recently summarised as follows: In the Indo-European past, the boys first moved into the category of the (armed) youths and then, as members of the war-band of unmarried and landless young men, engaged in predatory wolf-like behaviour on the edges of ordinary society, living off hunting and raiding with their older trainers/models. Then about the age of twenty they entered into the tribe proper as adults (Petrosyan 2011: 345). The activities of the young war-bands were seasonal; during the rest of the year they lived within their households and communities, perhaps engaged in herding animals and other forms of farm labour. Such bands were mainly made up of younger sons, as inheritance was restricted to the oldest son. Thus, they formed a dynamic force that could be employed in pioneer migrations (Sergent 2003). Archaeological evidence of this institution has been documented in the Russian steppe from the Bronze Age onwards (Pike-Tay & Anthony 2016; Brown & Anthony in press).  Figure 1. Model of the social processes of exogamy transforming Yamnaya to Corded Ware Culture, and its subsequent migration as Corded Ware Culture leading to further adaptations and transformations. There is additional evidence to support the idea that males dominated the initial Yamnaya migrations and the formation of the early Corded Ware Culture: in burials from the earliest horizon, often with males, as in Tiefbrunn and Kujawy, there was no typical Corded Ware material culture. This was followed shortly afterwards by the deposit of A-type battle-axes in male burials, but there was as yet no pottery (Furholt 2014: 6, fig. 3). Corded Ware pottery appeared later in Northern Europe, and we may suggest that this did not happen until women with ceramic skills married into this culture and started to copy wooden, leather and woven containers in clay. This process began in the early phase both south and north of the Carpathians (Ivanova 2013; Frînculeasa et al. 2015). Some confirmation of such material transformations is found in a uniquely preserved find of the typical flat bowl with short feet made of wood (Muhl et al. 2010: 47), well suited for turning milk into yogurt or similar dairy products overnight. Its pottery version became a shared type throughout the Corded Ware Culture, and later the Bell Beaker Culture. We may also note that pastoral economies historically tend to dominate agrarian economies, as they are both more mobile and more warlike in their behaviour. Such a pattern of economic and social dominance, reflected in taking wives from farming cultures while sending young males in organised war-bands to settle in new territories, would explain both the genetic and linguistic dominance of the Yamnaya steppe migrations, the results of which we can observe to this day. Figure 1 summarises these transformative processes in a model. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 15, 2019 5:26:46 GMT

Two recent palaeogenetic studies have identified a movement of Yamnaya peoples from the Eurasian steppe to Central Europe in the third millennium BC. Their findings are reminiscent of Gustaf Kossinna's equation of ethnic identification with archaeological culture. Rather than a single genetic transmission from Yamnaya to the Central European Corded Ware Culture, there is considerable evidence for centuries of connections and interactions across the continent, as far as Iberia. The author concludes that although genetics has much to offer archaeology, there is also much to be learned in the other direction. This article should be read in conjunction with that by Kristiansen et al. (2017), also in this issue. Language dispersal and the formation of Proto-Germanic in northern Europe These local processes of social integration between intruding Yamnaya/Corded Ware populations and remnant Neolithic populations can be applied to language dispersal. We should expect that the transformation from Proto-Indo-European to Pre-Proto Germanic would reveal the same kind of hybridisation between an earlier Neolithic language of the Funnel Beaker Culture, and the incoming Proto-Indo-European language. This is precisely what recent linguistic research has been able to demonstrate (Kroonen & Iversen in press). In their study on the formation of Proto-Germanic in Northern Europe, Kroonen and Iversen document a bundle of linguistic terms of non-Indo-European origin linked to agriculture that were adopted by Indo-European-speaking groups who were not fully fledged farmers. The most plausible, and perhaps the only possible, context for this to have happened would be the introduction of Proto-Germanic by the intruding Yamnaya groups. Archaeologically, this adoption can be understood from their interaction over several hundred years with late Funnel Beaker groups still residing in eastern Jutland and on the Danish islands, where they maintained a largely agricultural economy. From this we can conclude that terms linked to farming, and the cultivation of many important crops, were missing among the early Yamnaya/Corded Ware groups, who may well have acquired cereals (barley) mainly for the purpose of producing and consuming beer (Klassen 2005). In addition, we learn that the Neolithic language of the Funnel Beaker Culture was in all probability non-Indo-European. This process of language interaction is illustrated by the model in Figure 2. It illustrates that different Indo-European language branches were in contact with one and the same Neolithic tongue throughout Europe.  Figure 2. Schematic representation of how different Indo-European branches have absorbed words (circles) from a lost Neolithic language or language group (dark fill) in the reconstructed European linguistic setting of the third millennium BC, possibly involving one or more hunter-gatherer languages (light fill) (after Kroonen & Iversen in press). The new data conforms well to the reconstructed lexicon of Proto-Indo-European (Mallory & Adams 2006), which provides important clues that the subsistence strategy of early Indo-European-speaking societies was based on animal husbandry. It includes, for instance, terms related to dairy and wool production, horse breeding and wagon technology. Words for crops and land cultivation, however, have proved to be far more difficult to reconstruct. These results from historical linguistics are supported by similar evidence from archaeology (Andersen 1995; Kristiansen 2007). With the recent study by Kroonen and Iversen (in press), we can now demonstrate how social and economic interaction with existing Neolithic societies also had a corresponding linguistic imprint. This should not surprise us, as similar results are well documented from the interaction of Yamnaya societies with their northern Uralic-speaking neighbours (Parpola & Koskallio 2007). From this we may conclude that Funnel Beaker societies spoke a non-Indo-European language, and thus another pillar in support of the Anatolian hypothesis of farming/language dispersal (Renfrew 1987) has fallen. When the whole complex of wagon terminology is taken into account, i.e. ‘wheel’, ‘axle’, ‘nave’, ‘thill’, ‘yoke’, ‘hame’ (Anthony & Ringe 2015: tab. 1, fig. 1), the idea that all of those terms arose independently in the daughter languages seems extremely unlikely. When we add the evidence from ancient DNA, and the additional evidence from recent linguistic work discussed above, the Anatolian hypothesis must be considered largely falsified. Those Indo-European languages that later came to dominate in western Eurasia were those originating in the migrations from the Russian steppe during the third millennium BC. This integrated model of cultural, linguistic and genetic change explains the formation of Corded Ware Cultures as a result of local adaptations and of interaction between migrant Yamnaya populations and indigenous Neolithic cultures. The social institution of exogamy provided an integrating mechanism, despite sometimes hostile relations between intruding Corded Ware groups and residing Neolithic groups; the burials at Eulau are the most prominent example of this. Burial rituals also reveal a major difference in property relations and thus social organisation between existing Neolithic groups and intruding Yamnaya/Corded Ware groups. Both Yamnaya and Corded Ware groups shared individual burials under small family mounds, reflecting the transmission among individual families of animals and other property between generations. In contrast to this, the collective, megalithic or similar type burials of Neolithic groups reflected collective, clan-like shared ownership of property, animals and land. This collision of ideologies was played out gradually, with the Corded Ware political economy and interlinked cosmology as the winner once we enter the Bronze Age. Some influences from the Neolithic past, however, remained in both language and social organisation. This new historical interpretation rests on relatively solid ground, and represents a return to a more dramatic past than the prevailing model of cultural and technological transmissions. Some may not like it for its resemblance to an older paradigm of migrations as a primary cause of cultural change, as represented by Gustav Kossinna and Gordon Childe (Kristiansen 1998: 7–24), but we are now in a position to unravel the complexities behind the historical processes in much detail, and thus avoid the simplistic models of the past. Through this we realise that peaceful interaction and intermarriage between culturally and genetically different groups formed the day-to-day foundations of social life, interspersed with episodes of conflict. In the long term, however, the Corded Ware social formation had the potential to dominate, not least when supported by the migrations of related Bell Beaker groups. Together, their social and demographic force would finally create the foundations for the rise of the Bronze Age. We are only beginning to understand these processes, however, and much new evidence can be expected that will add detail and refine our models, while retaining the big picture. Antiquity Volume 91 Issue 356 |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 17, 2019 18:32:45 GMT

The cultural landscapes of prehistoric Europe in the third millennium cal bc have traditionally been classified in archaeological discourse in terms of extraordinarily large cultural units, including those of the Bell Beaker, Corded Ware, Yamnaya, or Globular Amphora cultures (Figure 1), which are thought to represent comparably uniform sets of material culture (Szmyt, 1999; Anthony, 2007; Harrison & Heyd, 2007; Vander Linden, 2006, 2007a; Shishlina, 2008; Furholt, 2014). These successive iterations of archaeological cultures were attributed in the early days of the discipline to wholesale migrations of prehistoric peoples (Kossinna, 1910; Childe, 1925; Glob, 1945). Since the 1970s, shifts in cultural groups have been refashioned as reflecting changes in social and economic systems (Kruk, 1973; Sherratt, 1981; Damm, 1991; Müller, 2001; Raetzel-Fabian 2001; Hübner, 2005; Kadrow 2008), as ideological packages and spheres of interaction (Shennan, 1976), or as referring to distinct marriage or elite networks, or less concretely defined interaction networks (Czebreszuk & Szmyt, 1998; Czebreszuk, 2002; Strahm, 2002; Furholt, 2003; Vander Linden, 2007a). Lately, more sophisticated migration models have emerged (Kristiansen, 1989, 2015; Anthony, 1990, 2007; Prescott, 2013; Prescott & Glørstad, 2015), which have most recently been reinforced by the new aDNA studies.  Figure 1. Simplified map showing the extent of the most important archaeological units of classification in the third millennium cal bc in Europe discussed in this text. Although these new aDNA data are overwhelmingly convincing, the interpretational frameworks associated with them require more discussion. In a critique of the traditional culture-historical approach, two major achievements in how the linkages between material culture and socio-cultural entities are conceptualized should be highlighted. The first broke the assumption that shared cultural material could be equated with a single culture group (best expressed in relation to Beakers and Corded Ware in Clarke, 1968 and Shennan, 1976). The second breakthrough came with the realization that the variability and multiplicity of social phenomena and agencies that constructed those seemingly homogenous material cultural groups were in fact underscored by diverse approaches to subsistence, settlement patterns, social practices, and ritual expressions (see Furholt, 2014). How far these two achievements have truly been accepted in the mainstream discourse of European archaeology is, however, open to question. An inclination to equate archaeological classification units (e.g. archaeological cultures) with distinct social phenomena (e.g. a population, an identity or ethnic group, a network, an ideology) and a tendency to view such social phenomena as clearly bounded and internally homogeneous remain widespread, even dominant, features in considerations of European prehistory (as discussed in Furholt, 2014). I argue that the renewed emphasis on migration as an explanatory framework, as it is expressed in the recent publications of aDNA studies, promotes an approach to the archaeological material that neglects these two central achievements. The ‘aDNA Revolution’ ‘The four successive genetic shifts highlight the biological cohesiveness of archaeological cultures such as the LBK [Linearbandkeramik], FBC [Funnel Beaker], CWC [Corded Ware], and BBC [Bell beaker] cultures …’. (Brandt et al., 2013: 261) ‘Our results support a view of European prehistory punctuated by two major migrations: first, the arrival of the first farmers during the Early Neolithic from the Near East, and second, the arrival of Yamnaya pastoralists during the Late Neolithic from the steppe.’ (Haak et al., 2015: 4)  Our picture of human population dynamics during the third millennium cal bc has changed dramatically in recent years with the explosion of aDNA research (Brandt et al., 2013; Lazaridis et al., 2014; Allentoft et al., 2015; Haak et al., 2015; Mathieson et al., 2015) indicating that the third millennium was a period of profound demographic change. These works have squarely placed the question of prehistoric mobility and migration back on the table and sparked lively discussions among archaeologists (e.g. Bánffy et al., 2012; Müller, 2013; Hofmann, 2014; Sjögren et al., 2016; Vander Linden, 2016). One matter of debate is that these aDNA publications link specific archaeological cultures to biological populations. For example, Haak et al. (2015) assert that a massive migration of a larger group of people from the area of the Yamnaya culture (located in present-day Russia and Ukraine) into central Europe led to the transformation of the latter region through the addition of steppe-related pastoralist ways of life to the traditional agricultural communities of central Europe. Among these were elements of a pastoral economy, distinct mortuary practices involving individual burials under small barrows emphasizing gender differences, and the new social role of male warriors, as expressed in burial customs connected to Corded Ware (Anthony, 2007; Kristiansen, 2015). Additionally, Haak et al. (2015) and Allentoft et al. (2015) suggest that the hypothesis that at least some Indo-European languages had originated in the steppes is supported by the new data. This is not the place to discuss the Indo-European issue (but see, for example, Prescott, 2013; Heggarty, 2014a, 2014b; Vander Linden, 2016). Here, I want to concentrate on the relationship between social processes and the molecular biological data and the tensions arising from the differential perspectives of archaeological and biological research. The articles mentioned above provide exciting new insights into prehistoric demographic processes that were previously undetectable by traditional archaeological approaches, but there remains an imbalance in the elaboration of molecular biological work and statistical inferences on the one hand, and social theory applied to interpret these results in the context of prehistoric social and cultural phenomena on the other. Such an imbalance seems to be a widespread pattern and source of tension between the genetic and the archaeological perspective. Already, in the context of the use of modern mtDNA studies for the understanding of prehistoric processes (Ammermann & Cavalli-Sforza, 1984; Renfrew & Boyle, 2000), Bandelt et al. (2003) criticize the weakness of the concept of population in general, and specifically how populations are constructed in these studies, where they are more or less equated which modern nation states. They also criticize the use of simplistic assumptions used to model population history (‘models of random-mating populations of constant sizes’), which speaks of ‘an insufficient attention to the resources of other disciplines’, a kind of positivism with which the data are used, and a lack of any archaeologically or anthropologically informed theory to take into account social and cultural factors that are known to influence population history (Bandelt et al., 2003: 103).  It seems that the problems pointed out by Bandelt et al. have persisted into the newer aDNA studies; indeed, they very much reflect the main issues discussed, especially the problematic definition of populations, and the simplification of assumptions and concepts about social groups and processes through a lack of engagement with archaeological and anthropological theory. The early articles (for example Bramanti et al., 2009; Haak et al., 2010) that used prehistoric mtDNA found a marked and stunning discontinuity between European hunter-gatherers and Early Neolithic individuals. These studies were, however, also criticized for constructing a hunter-gatherer population where individuals were scattered in space and time (e.g. Bánffy et al., 2012). Although overwhelming genetic evidence has made the case for the introduction of Neolithic ways of life into Europe being associated with a substantial demographic influx (see e.g. Hofmann, 2014), the underlying block-like concepts of hunter-gatherers vs farmers and the monolithic use of terms like migration vs diffusion actually obscures the Neolithisation process in all its complexity and diversity (as has been suggested, for example, by Schade & Schade-Lindig, 2010; Bickle & Whittle, 2013; Thomas, 2013; Hoffmann, 2014). The same simplifications are also applied in studies on the third millennium, and there they become even more problematic because of the more complicated situation regarding archaeological classification in this period. It should be stressed that the imbalance between the perspective of the natural sciences and the anthropological view described here is in part also due to conceptual problems within the archaeological discourse. The reification of classification units, the construction of homogeneous and clearly bounded cultural groups, the lack of elaboration in the conceptualization of migration as a social process can be, and have been, issues raised against archaeological research on the third millennium (e.g. by Kristiansen, 1989; Shennan, 1989; Anthony, 1990; Roberts & Vander Linden, 2011; Furholt, 2014), where they nevertheless persist as dominant frameworks of reference. |

|