Post by Admin on Mar 18, 2019 18:28:32 GMT

The 3rd millennium bc aDNA evidence

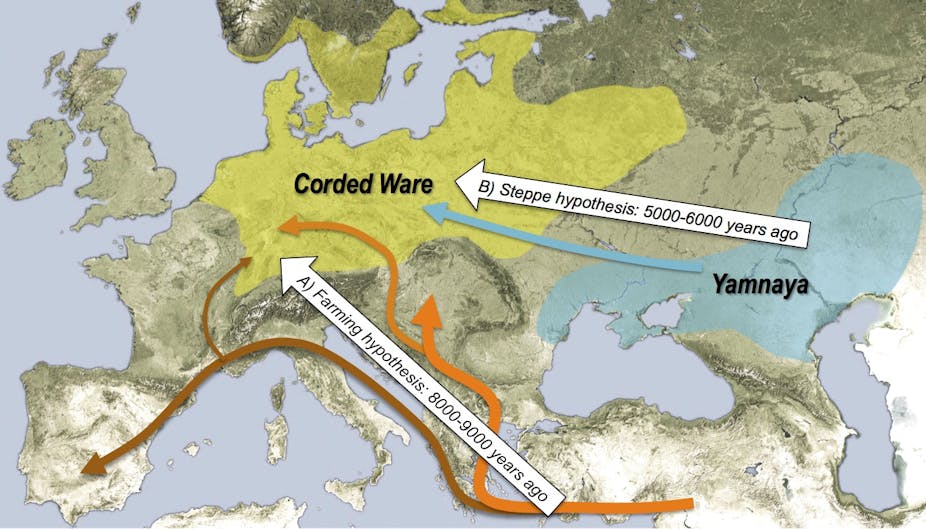

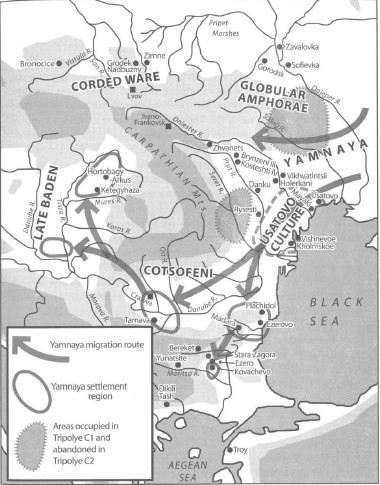

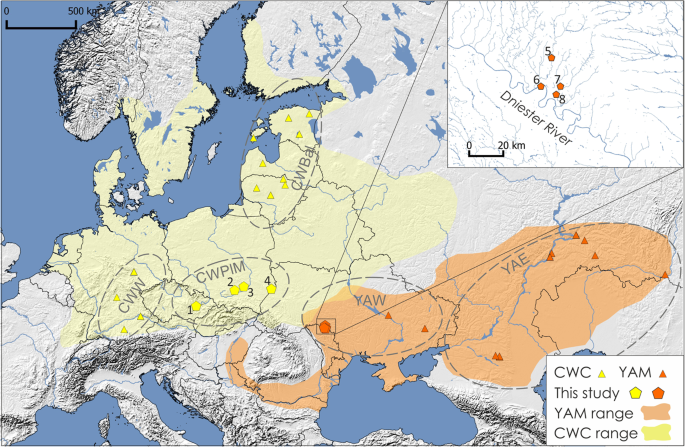

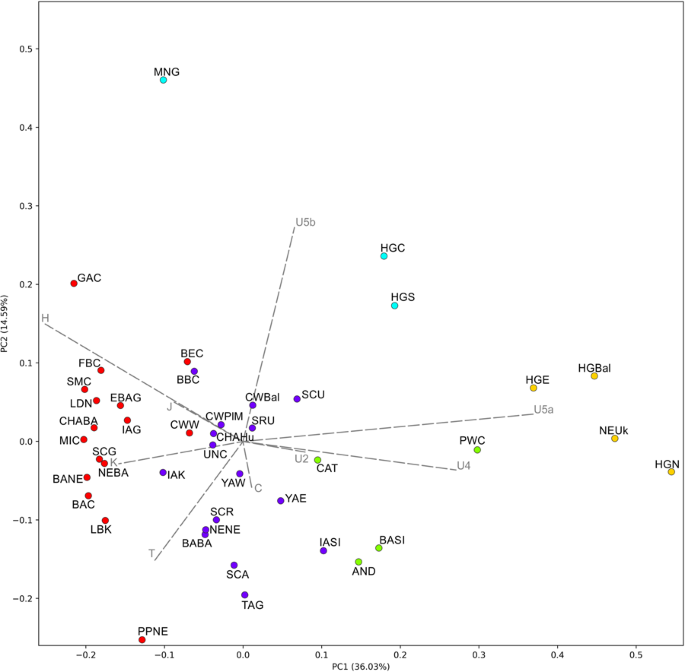

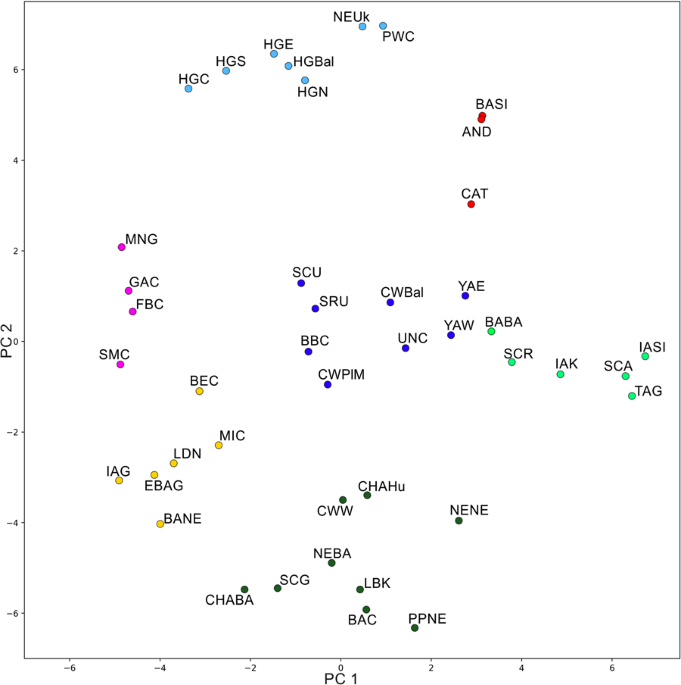

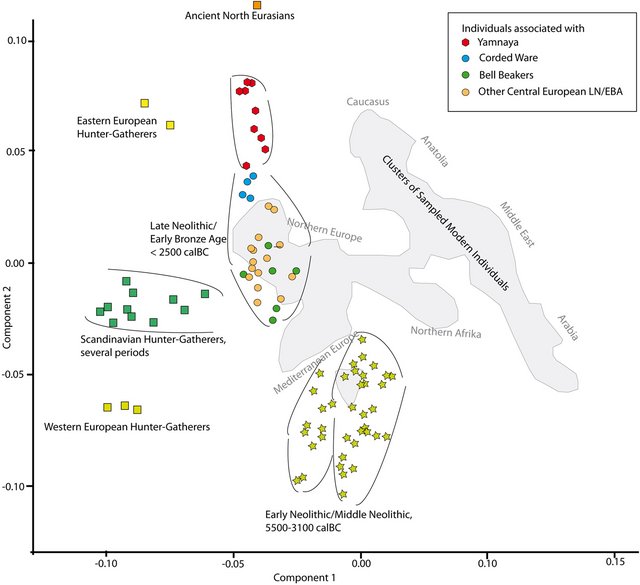

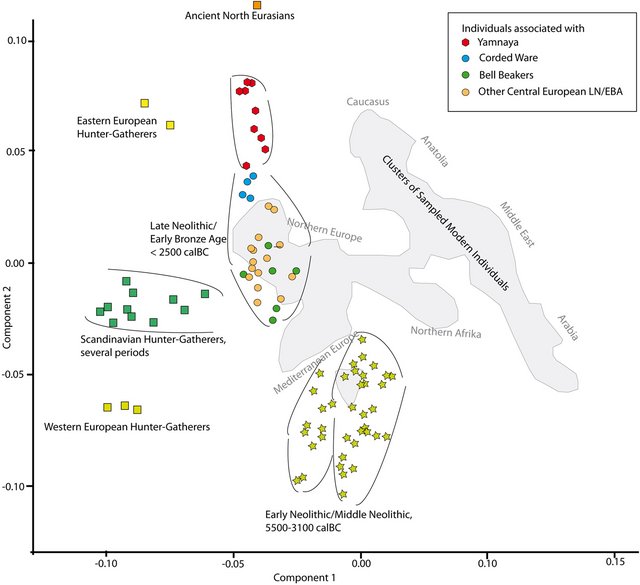

Brandt et al. (2013) already highlighted the significance of third-millennium transformations using mtDNA, pointing to two major events in population dynamics affecting their central German sample, which they identify with genetic influx from the east, connected to the archaeological Corded Ware and Kurgan, or Yamnaya, cultures, and from the West, linked to the archaeological Bell Beakers (Brandt et al., 2013: 261). This immediately seemed convincing, given the geographical location of these archaeological units of classification, the Corded Ware and Yamnaya encompassing central and eastern Europe, the Bell Beakers stretching from Morocco and the Iberian peninsula into central and northern Europe (see Figure 1). Not much later, Lazaridis et al. (2014), Haak et al. (2015), and Allentoft et al. (2015) presented patterns of similarities/distances of nuclear SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) of a constantly growing number of prehistoric individuals from the Palaeolithic to the Early Bronze Age, and convincingly argued that the modern central and northern European gene pool can best be explained when three distinct sources are assumed. These are: 1) the Early Neolithic farmers of Europe; 2) European hunter-gatherers (western European and Scandinavian); and 3) ancient north-Eurasian hunter-gatherers (Lazaridis et al., 2014) or eastern European hunter-gatherers (Haak et al., 2015). These three sources are represented as clusters or isolated instances of samples when they are projected onto the first two axes of a principal component analysis (PCA) of a dataset of 2345 modern western Eurasian individuals (see Figure 2) and ADMIXTURE analysis. Since in the Haak et al. (2015) sample all individuals dating to after 2500 cal bc—starting with four Corded Ware individuals—are clustered separately from the Neolithic individuals dating to before 3000 cal bc, the impact of the third source, the northern Eurasian/eastern European source, must have reached central and northern Europe at that time. However, in line with what Patterson et al. (2012) and Gómez-Sánchez et al. (2014) had previously indicated, these new nuclear SNP studies did not replicate the Brandt et al. (2013) finding of a genetic influx from the Iberian peninsula into central Europe in connection with Bell Beakers. Consequently, they place a new emphasis on migration from the east.

Figure 2. The main similarity patterns indicated by a principal component analysis (PCA) for modern and prehistoric samples as published by Haak et al. (2015), re-drawn from their fig. 2. The most important feature for the third millennium cal bc is the gap between the Early and Middle Neolithic cluster and the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age cluster, closer to the Yamnaya cluster.

The findings of Haak et al. (2015) were replicated, with a constantly growing base of individuals sampled, by Allentoft et al. (2015) and Mathieson et al. (2015). However, when it comes to working out the processes underlying the social, economic, or demographic phenomena that could explain these patterns, all these studies contain issues that require more discussion from an anthropological and archaeological point of view.

To illustrate some of these problems, I shall concentrate on Haak et al. (2015), because they most explicitly spell out their premises and arguments.

The first major issue is that the use of archaeological cultures as indicators of human biological populations has its problems (Clarke, 1968; Shennan, 1989; Wotzka, 1993; Furholt, 2008a). One can argue that such a procedure is acceptable as a heuristic tool to provide some spatial and temporal proximity in a sample of individuals, but there is a real and high danger of reifying these populations—to start treating them as genuine biological and even social groups. This can be seen, for example, in formulations like ‘a new social and economic formation, […] named Corded Ware’ (Allentoft et al., 2015: 168), or ‘a new class of master artisans known as the Sintashta culture emerged in the Urals’ (Allentoft et al., 2015). It is also visible in the following quotation, which interprets and contextualizes the similarity of the genetic profiles shown in Figure 2:

‘The Corded Ware shared elements of material culture with steppe groups such as the Yamnaya, although whether this reflects movements of people has been contentious. Our genetic data provide direct evidence of migration and suggest that it was relatively sudden.’ (Haak et al., 2015: 2)

This illustrates very well some of the main points which distort our archaeological debates on third-millennium social and cultural processes, and these (primarily archaeological) issues are, it seems, adopted into the interdisciplinary approach. A first issue concerns the four individuals from a single cemetery in Esperstedt, central Germany, taken to represent the whole Corded Ware culture; this unit of classification for archaeological features and finds is implicitly treated as if it represented a specific group of people. One can agree that a high degree of genetic similarity in samples that are located 2600 km from each other is an indication for some kind of long-distance movement, but what is being proposed here in decisive terms is a very specific scenario. The Yamnaya, a term referring to a set of specific traits of burial practice and material culture, and the Corded Ware, also referring to particular types of pottery, weapons, tools, and burial practices, are used as if they represent distinct social groups, as becomes clear in the language used: ‘The Corded Ware are genetically closest to the Yamnaya’ (Haak et al., 2015: 2).

The equation of biological groups with archaeological cultures claimed by Kossinna (1911) had already been dismissed by Childe (1929). Moreover, the notion that archaeological cultures could represent even distinct social groups has also been dismissed, as anthropological research has shown that the relationships between material culture and social identities are much more complex (Hodder, 1982; Wotzka, 1997; Hahn, 2005; Brather & Wotzka, 2006). It should not be claimed that there is absolutely no connection between cultures (or better, traits of material culture) and social identities (e.g. Barth, 1982), but anthropology shows us that material culture may be linked to diverse and changing layers of identities, may be actively used for different purposes by social actors, and may have a different and changing impact on social interaction. Additionally, archaeological cultures like the Corded Ware, with a distribution area extending from Switzerland to Russia (see Figure 1) and a considerable variability of things and practices within this area, are highly unlikely to represent a particular social group or population (Furholt, 2014). The same is true for the Bell Beakers (Vander Linden, 2006, 2007a).

The argument that the Corded Ware phenomenon ‘shares elements of material culture with steppe groups, including Yamnaya’ is correct, but should be seen in the light of Corded Ware actually sharing elements of material culture with more or less every contemporary, preceding, or subsequent archaeological unit, be it Funnel Beakers, Pitted Ware, Globular Amphora, Baden, Bell Beakers, Unetice, Mierzanowice, and others (Beran, 1992; Bertemes et al., 2002; Furholt, 2003; Hübner, 2005; Włodarczak, 2006).

Finally, the argument about whether these shared elements of material culture actually reflect movements of people illustrates an underlying (and very common) conceptual problem. What the debates really should address is what specific kinds of movement we are dealing with. All too often this question is reduced to a binary choice between migration and diffusion, as if only these two scenarios were possible. Our conceptions of the movement of people are sorely underdeveloped, which applies as much to those who have favoured migration as an explanatory framework as to those who have opposed it. It is one of the great achievements of studies like Haak et al. (2015) to make clear that we must confront such migration phenomena, but the challenge is to realize that there is no such thing as a migration that would either occur or not occur; instead there is a wide range of processes involving human mobility, which are subsumed under the concept of migration (e.g. Anthony, 1990, 1997; Chapman & Hamerow, 1997; Burmeister, 2000; Prien, 2005; Cabana & Clarke, 2011; Cameron, 2013; Kaiser & Schier, 2013; van Dommelen, 2014; Brettell, 2014) and that of diffusion. In archaeological discussions, migration is all too often seen as a unified and clearly bounded phenomenon—a single-event mass migration—in the same way as the Yamnaya culture is seen as a single social entity, and the Corded Ware culture a different one, and this paradigm of ‘wholeness’ (Greenblatt, 2009) clearly forms the background of the emphasis laid on this specific form of migration.

To back up the claim of a massive and rapid migration, Haak et al. (2015) use an additional argument, namely the high degree of similarity between individuals connected to the Corded Ware and Yamnaya material cultures, seen in the data clusters in the PCA (Figure 2) and in the values achieved by ADMIXTURE analysis, as opposed to the other Late Neolithic and Bronze Age individuals. As the PCA shows, the four individuals assigned to the Corded Ware from Esperstedt are said to be the earliest individuals, and they are additionally placed closest to the ten individuals connected to Yamnaya and furthest away from the Early and Middle Neolithic individuals. Haak et al. (2015) interpret this as consistent with a single migration event and a successive resurgence of the local population, visible in the position of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age individuals closer to the earlier, Early and Middle Neolithic individuals. This interpretation of the patterns seems to overstate the explanatory powers of the PCA. The notion of a generally closer connection of Corded Ware individuals to Yamnaya individuals than the other Late Neolithic samples is much less clear in a different study using different samples connected to Corded Ware (Allentoft et al., 2015). Here, seven individuals with Corded Ware connections from Sweden, Poland, the Baltic, and southern Germany are placed just within the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age cluster, more clearly separated from the Yamnaya cluster (Allentoft et al., 2015: fig. 2). Allentoft et al. write:

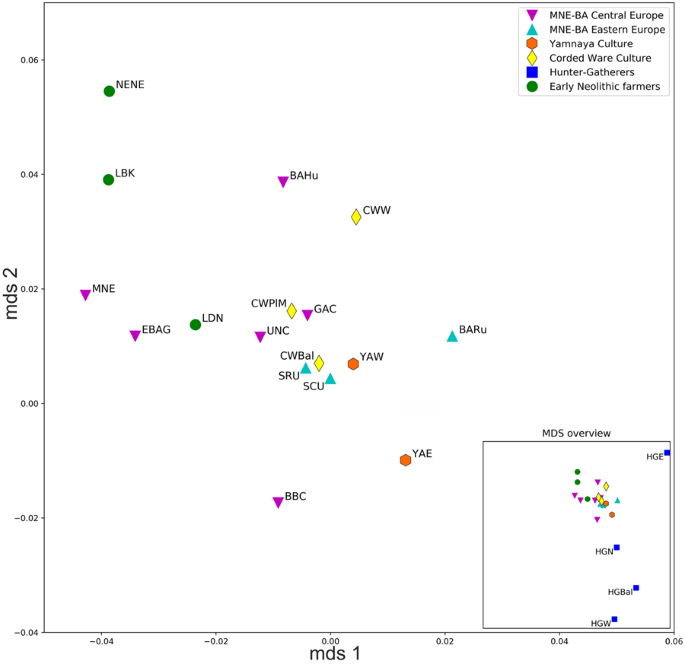

‘Although European Late Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures such as Corded Ware, Bell Beakers, Unetice, and the Scandinavian cultures are genetically very similar to each other [and placed clearly outside the Yamnaya cluster; addition by author], they still display a cline of genetic affinity with Yamnaya, with highest levels in Corded Ware, lowest in Hungary, and central European Bell Beakers being intermediate.’ (Allentoft et al., 2015: 169)

Brandt et al. (2013) already highlighted the significance of third-millennium transformations using mtDNA, pointing to two major events in population dynamics affecting their central German sample, which they identify with genetic influx from the east, connected to the archaeological Corded Ware and Kurgan, or Yamnaya, cultures, and from the West, linked to the archaeological Bell Beakers (Brandt et al., 2013: 261). This immediately seemed convincing, given the geographical location of these archaeological units of classification, the Corded Ware and Yamnaya encompassing central and eastern Europe, the Bell Beakers stretching from Morocco and the Iberian peninsula into central and northern Europe (see Figure 1). Not much later, Lazaridis et al. (2014), Haak et al. (2015), and Allentoft et al. (2015) presented patterns of similarities/distances of nuclear SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) of a constantly growing number of prehistoric individuals from the Palaeolithic to the Early Bronze Age, and convincingly argued that the modern central and northern European gene pool can best be explained when three distinct sources are assumed. These are: 1) the Early Neolithic farmers of Europe; 2) European hunter-gatherers (western European and Scandinavian); and 3) ancient north-Eurasian hunter-gatherers (Lazaridis et al., 2014) or eastern European hunter-gatherers (Haak et al., 2015). These three sources are represented as clusters or isolated instances of samples when they are projected onto the first two axes of a principal component analysis (PCA) of a dataset of 2345 modern western Eurasian individuals (see Figure 2) and ADMIXTURE analysis. Since in the Haak et al. (2015) sample all individuals dating to after 2500 cal bc—starting with four Corded Ware individuals—are clustered separately from the Neolithic individuals dating to before 3000 cal bc, the impact of the third source, the northern Eurasian/eastern European source, must have reached central and northern Europe at that time. However, in line with what Patterson et al. (2012) and Gómez-Sánchez et al. (2014) had previously indicated, these new nuclear SNP studies did not replicate the Brandt et al. (2013) finding of a genetic influx from the Iberian peninsula into central Europe in connection with Bell Beakers. Consequently, they place a new emphasis on migration from the east.

Figure 2. The main similarity patterns indicated by a principal component analysis (PCA) for modern and prehistoric samples as published by Haak et al. (2015), re-drawn from their fig. 2. The most important feature for the third millennium cal bc is the gap between the Early and Middle Neolithic cluster and the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age cluster, closer to the Yamnaya cluster.

The findings of Haak et al. (2015) were replicated, with a constantly growing base of individuals sampled, by Allentoft et al. (2015) and Mathieson et al. (2015). However, when it comes to working out the processes underlying the social, economic, or demographic phenomena that could explain these patterns, all these studies contain issues that require more discussion from an anthropological and archaeological point of view.

To illustrate some of these problems, I shall concentrate on Haak et al. (2015), because they most explicitly spell out their premises and arguments.

The first major issue is that the use of archaeological cultures as indicators of human biological populations has its problems (Clarke, 1968; Shennan, 1989; Wotzka, 1993; Furholt, 2008a). One can argue that such a procedure is acceptable as a heuristic tool to provide some spatial and temporal proximity in a sample of individuals, but there is a real and high danger of reifying these populations—to start treating them as genuine biological and even social groups. This can be seen, for example, in formulations like ‘a new social and economic formation, […] named Corded Ware’ (Allentoft et al., 2015: 168), or ‘a new class of master artisans known as the Sintashta culture emerged in the Urals’ (Allentoft et al., 2015). It is also visible in the following quotation, which interprets and contextualizes the similarity of the genetic profiles shown in Figure 2:

‘The Corded Ware shared elements of material culture with steppe groups such as the Yamnaya, although whether this reflects movements of people has been contentious. Our genetic data provide direct evidence of migration and suggest that it was relatively sudden.’ (Haak et al., 2015: 2)

This illustrates very well some of the main points which distort our archaeological debates on third-millennium social and cultural processes, and these (primarily archaeological) issues are, it seems, adopted into the interdisciplinary approach. A first issue concerns the four individuals from a single cemetery in Esperstedt, central Germany, taken to represent the whole Corded Ware culture; this unit of classification for archaeological features and finds is implicitly treated as if it represented a specific group of people. One can agree that a high degree of genetic similarity in samples that are located 2600 km from each other is an indication for some kind of long-distance movement, but what is being proposed here in decisive terms is a very specific scenario. The Yamnaya, a term referring to a set of specific traits of burial practice and material culture, and the Corded Ware, also referring to particular types of pottery, weapons, tools, and burial practices, are used as if they represent distinct social groups, as becomes clear in the language used: ‘The Corded Ware are genetically closest to the Yamnaya’ (Haak et al., 2015: 2).

The equation of biological groups with archaeological cultures claimed by Kossinna (1911) had already been dismissed by Childe (1929). Moreover, the notion that archaeological cultures could represent even distinct social groups has also been dismissed, as anthropological research has shown that the relationships between material culture and social identities are much more complex (Hodder, 1982; Wotzka, 1997; Hahn, 2005; Brather & Wotzka, 2006). It should not be claimed that there is absolutely no connection between cultures (or better, traits of material culture) and social identities (e.g. Barth, 1982), but anthropology shows us that material culture may be linked to diverse and changing layers of identities, may be actively used for different purposes by social actors, and may have a different and changing impact on social interaction. Additionally, archaeological cultures like the Corded Ware, with a distribution area extending from Switzerland to Russia (see Figure 1) and a considerable variability of things and practices within this area, are highly unlikely to represent a particular social group or population (Furholt, 2014). The same is true for the Bell Beakers (Vander Linden, 2006, 2007a).

The argument that the Corded Ware phenomenon ‘shares elements of material culture with steppe groups, including Yamnaya’ is correct, but should be seen in the light of Corded Ware actually sharing elements of material culture with more or less every contemporary, preceding, or subsequent archaeological unit, be it Funnel Beakers, Pitted Ware, Globular Amphora, Baden, Bell Beakers, Unetice, Mierzanowice, and others (Beran, 1992; Bertemes et al., 2002; Furholt, 2003; Hübner, 2005; Włodarczak, 2006).

Finally, the argument about whether these shared elements of material culture actually reflect movements of people illustrates an underlying (and very common) conceptual problem. What the debates really should address is what specific kinds of movement we are dealing with. All too often this question is reduced to a binary choice between migration and diffusion, as if only these two scenarios were possible. Our conceptions of the movement of people are sorely underdeveloped, which applies as much to those who have favoured migration as an explanatory framework as to those who have opposed it. It is one of the great achievements of studies like Haak et al. (2015) to make clear that we must confront such migration phenomena, but the challenge is to realize that there is no such thing as a migration that would either occur or not occur; instead there is a wide range of processes involving human mobility, which are subsumed under the concept of migration (e.g. Anthony, 1990, 1997; Chapman & Hamerow, 1997; Burmeister, 2000; Prien, 2005; Cabana & Clarke, 2011; Cameron, 2013; Kaiser & Schier, 2013; van Dommelen, 2014; Brettell, 2014) and that of diffusion. In archaeological discussions, migration is all too often seen as a unified and clearly bounded phenomenon—a single-event mass migration—in the same way as the Yamnaya culture is seen as a single social entity, and the Corded Ware culture a different one, and this paradigm of ‘wholeness’ (Greenblatt, 2009) clearly forms the background of the emphasis laid on this specific form of migration.

To back up the claim of a massive and rapid migration, Haak et al. (2015) use an additional argument, namely the high degree of similarity between individuals connected to the Corded Ware and Yamnaya material cultures, seen in the data clusters in the PCA (Figure 2) and in the values achieved by ADMIXTURE analysis, as opposed to the other Late Neolithic and Bronze Age individuals. As the PCA shows, the four individuals assigned to the Corded Ware from Esperstedt are said to be the earliest individuals, and they are additionally placed closest to the ten individuals connected to Yamnaya and furthest away from the Early and Middle Neolithic individuals. Haak et al. (2015) interpret this as consistent with a single migration event and a successive resurgence of the local population, visible in the position of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age individuals closer to the earlier, Early and Middle Neolithic individuals. This interpretation of the patterns seems to overstate the explanatory powers of the PCA. The notion of a generally closer connection of Corded Ware individuals to Yamnaya individuals than the other Late Neolithic samples is much less clear in a different study using different samples connected to Corded Ware (Allentoft et al., 2015). Here, seven individuals with Corded Ware connections from Sweden, Poland, the Baltic, and southern Germany are placed just within the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age cluster, more clearly separated from the Yamnaya cluster (Allentoft et al., 2015: fig. 2). Allentoft et al. write:

‘Although European Late Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures such as Corded Ware, Bell Beakers, Unetice, and the Scandinavian cultures are genetically very similar to each other [and placed clearly outside the Yamnaya cluster; addition by author], they still display a cline of genetic affinity with Yamnaya, with highest levels in Corded Ware, lowest in Hungary, and central European Bell Beakers being intermediate.’ (Allentoft et al., 2015: 169)