|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 23, 2019 18:42:53 GMT

By analyzing ancient mitochondrial genomes, we show that people from the eastern and western Corded Ware culture were genetically differentiated. Individuals associated with the eastern Corded Ware culture (from present day Poland and the Czech Republic) shared close maternal genetic affinity with individuals associated with the Yamnaya horizon while the genetic differentiation between individuals associated with the western Corded Ware culture (from present-day Germany) and the Yamnaya horizon was more extensive. This decreasing cline of steppe related ancestry from east to west likely reflect the direction of the steppe migration. It also indicates that more people with steppe-related ancestry, likely both females and males, contributed to the formation of the population associated with the eastern Corded Ware culture. Similarly, closer genetic affinity to populations associated with Yamnaya horizon can be observed in Baltic Corded Ware groups, which confirms earlier indications of a direct migrations from the steppe not only to the west but also to the north, into the eastern Baltic region18,19,55. The mitochondrial data further suggests that with increased distance from the source populations of the steppe, the contribution of local people increase, which is seen as an increase of maternal lineages of Neolithic farmer ancestry in individuals associated with the western Corded Ware culture.  Among the analyzed samples, we identified two Catacomb culture-associated individuals (poz220 and poz221) belonging to hg X4. They are the first ancient individuals assigned to this particular lineage. Haplogroup X4 is rare among present day populations and has been found only in one individual each from Central Europe, Balkans, Anatolia and Armenia56,57. Moreover, we have reported mtDNA haplotypes that might be associated with the migration from the steppe and point to genetic continuity in the north Pontic region from Bronze Age until the Iron Age. These haplotypes were assigned to hgs U5, U4, U2 and W3. MtDNA hgs U5a and U4, identified in this study among Yamnaya, Late Eneolithic and Corded Ware culture-associated individuals, have previously been found in high frequencies among northern and eastern hunter-gatherers19,23,28,55,58,59. Moreover, they appeared in the north Pontic region in populations associated with Mesolithic (hg U5a)45, Eneolithic (Post-Stog) (hg U4)24, Yamnaya (hgs U5, U5a)24, Catacomb (hgs U5 and U5a)24 and Iron Age Scythians (hg U5a)60, suggesting genetic continuity of these particular mtDNA lineages in the Pontic region from, at least, the Bronze Age. Hgs U5a and U4-carrying populations were also present in the eastern steppe, along with individuals from the Yamnaya culture from Samara region14,17, the Srubnaya23 and the Andronovo from Russia14. Interestingly, hg U4c1 found in the Yamnaya individual (poz224) has so-far been found only in two Bell Beaker- associated individuals61 and one Late Bronze Age individual from Armenia14, which might suggest a steppe origin for hg U4c1. A steppe origin can possibly also be assigned to hg U4a2f, found in one individual (poz282) but not reported in any other ancient populations to date, and to U5a1- the ancestral lineage of U5a1b, reported for individual poz232, which was identified not only in Corded Ware culture-associated population from central and eastern Europe55,61 but also in representatives of Catacomb culture from the north Pontic region24, Yamnaya from Bulgaria and Russia17,46, Srubnaya23 and Andronovo62-associated groups. Hg U2e, reported for Late Eneolithic individual (poz090), was also identified in western Corded Ware culture-associated individual23 and in succeeding Sintashta14, Potapovka and Andronovo23 groups, suggesting possible genetic continuity of U2e1 in the western part of the north Pontic region.  Hgs W3a1 and W3a1a, found in two Yamnaya individuals from this study (poz208 and poz222), were also identified in Yamnaya-associated individuals from the Russia Samara region17 and later in Únětice and Bell Beaker groups from Germany61,63, supporting the idea of an eastern European steppe origin of these haplotypes and their contribution to the Yamnaya migration toward the central Europe. The W3a1 lineage was not identified in Neolithic times and, thus, we assume that it appeared in the steppe region for the first time during the Bronze Age. Notably, hgs W1 and W5, which predate the Bronze Age in Europe, were found only in individuals associated with the early Neolithic farmers from Starčevo in Hungary (hg W5)64, early Neolithic farmers from Anatolia (hg W1-T119C)23, and from the Schöningen group (hg W1c)61 and Globular Amphora culture from Poland (hg W5)45. This study is the first to present mitochondrial genome data from the population associated with Corded Ware culture from the south-eastern part of present-day Poland. As this area is geographically close to the steppe region, it provides us with a better picture of the early steppe migration between 3,000 and 2,500 BC. Although our results indicate a contribution of females as well as males to the formation of populations associated with eastern Corded Ware culture, more detailed studies of X chromosome data are needed to clearly resolve female and male migrations, especially between the western Pontic steppe and the eastern part of the North European Plain. Conclusions Ancient mitochondrial genome data from the western Pontic region and, for the first time, from the south-eastern part of present day Poland, show close genetic affinities between populations associated with the eastern Corded Ware culture and the Yamnaya horizon. This indicates that females had also participated in the migration from the steppe. Furthermore, greater mtDNA differentiation between populations associated with the western Corded Ware culture and the Yamnaya horizon points to an increased contribution of individuals with a maternal Neolithic farmer ancestry with increasing geographic distance from the steppe region, forming the population associated with the western Corded Ware culture. Among the analyzed samples, we identified, for the first time in ancient populations, two Catacomb culture-associated individuals belonging to the now-rare mtDNA hg X4. Scientific Reportsvolume 8, Article number: 11603 (2018) |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 8, 2019 18:18:23 GMT

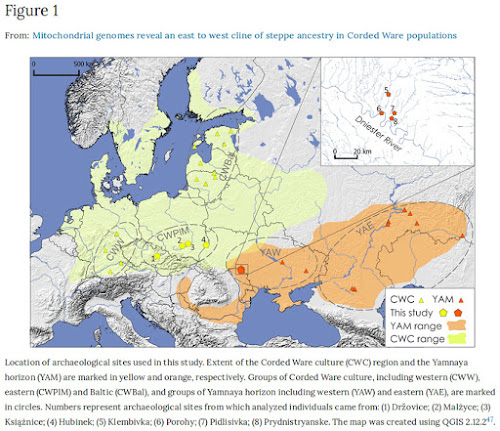

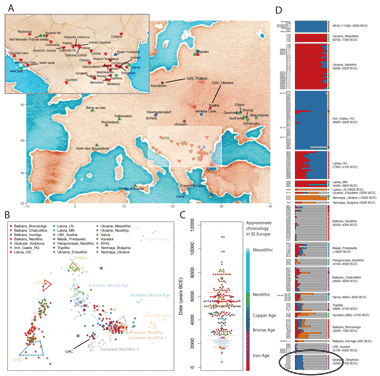

The third millennium BCE was a period of major cultural and demographic changes in Europe that signaled the beginning of the Bronze Age. People from the Pontic steppe expanded westward, leading to the formation of the Corded Ware complex and transforming the genetic landscape of Europe. At the time, the Globular Amphora culture (3300–2700 BCE) existed over large parts of Central and Eastern Europe, but little is known about their interaction with neighboring Corded Ware groups and steppe societies. Here we present a detailed study of a Late Neolithic mass grave from southern Poland belonging to the Globular Amphora culture and containing the remains of 15 men, women, and children, all killed by blows to the head. We sequenced their genomes to between 1.1- and 3.9-fold coverage and performed kinship analyses that demonstrate that the individuals belonged to a large extended family. The bodies had been carefully laid out according to kin relationships by someone who evidently knew the deceased. From a population genetic viewpoint, the people from Koszyce are clearly distinct from neighboring Corded Ware groups because of their lack of steppe-related ancestry. Although the reason for the massacre is unknown, it is possible that it was connected with the expansion of Corded Ware groups, which may have resulted in competition for resources and violent conflict. Together with the archaeological evidence, these analyses provide an unprecedented level of insight into the kinship structure and social behavior of a Late Neolithic community.  In 2011, archaeological excavations near the village of Koszyce in southern Poland uncovered a ca. 5,000-y-old mass grave (Fig. 1) associated with the Globular Amphora culture and containing the remains of 15 men, women, and children who had been killed, but carefully buried with rich grave goods (1). Closer study of the skeletons (2) revealed that the individuals had all been killed by blows to the head, possibly during a raid on their settlement. To shed light on this Late Neolithic community and the events that unfolded at Koszyce 5,000 y ago, we sequenced their genomes to between 1.1- and 3.9-fold coverage (Table 1) and performed genome-wide analyses to explore their genetic ancestry and kinship relations. In addition, we obtained 16 radiocarbon dates (SI Appendix, section 4 and Dataset S1) to narrow down the date of the massacre to 2880–2776 BCE (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). We also provide a detailed description of the injuries (SI Appendix, section 3), and strontium isotope measurements of dental enamel provide information on mobility and residence patterns (SI Appendix, section 5). Together, the analyses enable us to draw up a remarkably detailed picture of this Late Neolithic community, including their genetic ancestry, physical appearance, kinship structure, and social organization.  Fig. 1. The mass grave at Koszyce, southern Poland. (A) Photograph of the 15 skeletons and grave goods buried at Koszyce site 3 (reproduced with permission from ref. 2). (B) Map of Poland showing the location of Koszyce and four other Globular Amphora/Złota group sites included in this study. To investigate their genetic ancestry, we merged the 15 Koszyce genomes with the Human Origins data set (3), as well as 168 previously published ancient genomes (Dataset S6). In addition, we included genome-wide data for nine individuals from four contemporary, neighboring sites in southern Poland belonging to the Globular Amphora culture and its Złota group variant that we sequenced to between 0.2- and 1-fold coverage (Dataset S3). We then performed a principal component analysis and found that all 24 Globular Amphora/Złota group individuals clustered with other previously sequenced Globular Amphora individuals (4, 5) and other Neolithic groups (Fig. 2A). This confirms earlier suggestions that the Globular Amphora people belonged to the Neolithic gene pool of Europe, as typified by early Anatolian farmers (4, 5).  Fig. 2. Genetic affinities of the Koszyce individuals and other GAC groups (here including Złota) analyzed in this study. (A) Principal component analysis of previously published and newly sequenced ancient individuals. Ancient genomes were projected onto modern reference populations, shown in gray. (B) Ancestry proportions based on supervised ADMIXTURE analysis (K = 3), specifying Western hunter-gatherers, Anatolian Neolithic farmers, and early Bronze Age steppe populations as ancestral source populations. LP, Late Paleolithic; M, Mesolithic; EN, Early Neolithic; MN, Middle Neolithic; LN, Late Neolithic; EBA, Early Bronze Age; PWC, Pitted Ware culture; TRB, Trichterbecherkultur/Funnelbeaker culture; LBK, Linearbandkeramik/Linear Pottery culture; GAC, Globular Amphora culture; Złota, Złota culture. To further investigate the ancestry of the Globular Amphora individuals, we performed a supervised ADMIXTURE (6) analysis, specifying typical western European hunter-gatherers (Loschbour), early Neolithic Anatolian farmers (Barcın), and early Bronze Age steppe populations (Yamnaya) as ancestral source populations (Fig. 2B). The results indicate that the Globular Amphora/Złota group individuals harbor ca. 30% western hunter-gatherer and 70% Neolithic farmer ancestry, but lack steppe ancestry. To formally test different admixture models and estimate mixture proportions, we then used qpAdm (7) and find that the Polish Globular Amphora/Złota group individuals can be modeled as a mix of western European hunter-gatherer (17%) and Anatolian Neolithic farmer (83%) ancestry (SI Appendix, Table S2), mirroring the results of previous studies (4, 5). |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 9, 2019 17:50:30 GMT

Kinship and Consanguinity. Analyses of ancient genomes can provide detailed information on the kinship structures and social organization of past communities (8⇓–10). At Koszyce, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis revealed the presence of six different maternal lineages, whereas analysis of the nonrecombining region of the Y chromosome showed that all males carried the same Y chromosome haplotype: I2a-L801 (Table 1). We then estimated genomic runs of homozygosity (ROH) and found that the Koszyce individuals were not particularly inbred. Although a slightly larger section of the Koszyce genomes is contained within ROH compared with typical modern European populations (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), this signal is mainly driven by an increased fraction of short ROH (<2 Mb), which is indicative of ancestral restrictions in population size rather than recent inbreeding. On the basis of genome-wide patterns of allelic identity-by-state (IBS), we computed kinship coefficients between all pairs of individuals and applied established cutoff values for possible kinship categories (Materials and Methods). We find that the Koszyce burial represents a large extended family connected via several first- and second-degree relationships (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S9).  Fig. 3. Kinship. (A) Artistic reconstruction of the Koszyce mass burial based partly on phenotypic traits inferred from the ancient genomes (reconstruction by Michał Podsiadło); (B) Schematic representation of the burial and pedigree plots showing kinship relations between the Koszyce individuals inferred from genetic data. (C) kinship network based on kinship coefficients inferred from IBS scores for pairs of Koszyce individuals showing first- and second-degree relationships. Kinship coefficients and R scores are reported in Dataset S7 and plotted in SI Appendix, Fig. S9. Overall, we identified four nuclear families in the grave, which are for the most part represented by mothers and their children (Fig. 3). Closely related kin were buried next to each other: a mother was buried cradling her child, and siblings were placed side by side. Evidently, these individuals were buried by people who knew them well and who carefully placed them in the grave according to familial relationships. For example, individual 14, the oldest individual in the grave, was buried close to her two sons (individuals 5 and 15), whereas individual 8, a 30–35-y-old woman, was buried with her teenage daughter (individual 9) and 5-y-old son (individual 13). Using genome-wide patterns of IBS, we were also able to reconstruct more complex relationships: individuals 5, 10, 11, and 15 all appear to be brothers, and yet they do not have the same mother (individual 14 is the mother of individuals 5 and 15, but not 10 and 11), suggesting that they might be half-brothers. However, all four of them share the same mitochondrial DNA haplotype, suggesting that their mothers might also have been related. Interestingly, the older males/fathers are mostly missing from the grave, suggesting that it might have been them who buried their kin. The only father present in the grave is individual 10, whose partner and son are placed together opposite him in the grave. In addition, there is a young boy (individual 7), aged 2–2.5 y, whose parents are not in the grave, but he is placed next to other individuals to whom he is closely related through various second-degree relationships. Finally, there is individual 3, an adult female, who does not seem to be genetically related to anyone in the group. However, her position in the grave close to individual 4, a young man, suggests that she may have been as close to him in life as she was in death. These biological data and burial arrangements show that the social relationships held to be most significant in these societies were identical with genetic and reproductive relationships. However, they also demonstrate that nuclear families were nested in larger, extended family groups, either permanently or for parts of the year.  Social Organization, Residence Patterns, and Subsistence Strategies. The presence of unrelated females and related males in the grave is interesting because it suggests that the community at Koszyce was organized along patrilineal lines of descent, adding to the mounting evidence that this was the dominant form of social organization among Late Neolithic communities in Central Europe (11, 12). Usually, patrilineal forms of social organization go hand in hand with female exogamy (i.e., the practice of women marrying outside their social group). Indeed, several studies (11, 12) have shown that patrilocal residence patterns and female exogamy prevailed in several parts of Central Europe during the Late Neolithic. At Koszyce, there is no clear difference in enamel 87Sr/86Sr ratios between males and females (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) that would suggest that the females are nonlocal. However, the high diversity of mtDNA lineages, combined with the presence of only a single Y chromosome lineage, is certainly consistent with a patrilocal residence system. Social organization is most often aligned with settlement and subsistence patterns, and several studies (13⇓–15) suggest that Globular Amphora communities and other related groups specialized in animal husbandry, often with a main focus on cattle, and that they moved around the landscape to seek new pastures for their animals at different times of the year (see SI Appendix, section 1 for a more detailed discussion). This form of mobility is likely to have included fission-fusion dynamics in which a larger social unit, similar to the extended family, would split up into smaller groups, perhaps nuclear families, for certain purposes and parts of the year (16). This dynamic could explain the relatively high variation we observe in the 87Sr/86Sr isotope signatures at Koszyce. Similar to strongly patrilineal modes of social organization, such pastoral economic strategies have often been linked to Corded Ware groups that introduced steppe genetic ancestry into Europe (7, 17), and the two (social organization and economic strategy) are probably linked: Pastoral ways of life involve a high level of mobility within vaguely defined territories and with the groups’ main economic capital, their animal herds, exposed across the landscape, and thus harbor a significant potential for conflict with neighboring groups. One ethnographically known cultural response to this situation is to adopt an aggressive strategy toward competing groups in which male dominance, including patrilineal kin alliance, and warrior-like values prevail (18). Although we cannot be certain that the people at Koszyce shared these values, we show that they were organized around patrilineal descent groups, demonstrating that this form of social organization was already present in communities before the expansion of the Corded Ware complex in Central and Eastern Europe (13, 14). Intergroup Conflict and Violence. All individuals buried in the mass grave at Koszyce exhibit extensive evidence of perimortem injuries (SI Appendix, section 3). The most common injuries are cranial fractures (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), which indicate that the individuals were killed by blows to the head. Overall, the nature of the injuries and the near absence of so-called parry fractures (i.e., injuries sustained to the upper limbs) suggest that the individuals were captured and executed, rather than killed in hand-to-hand combat. The evidence for violence at Koszyce fits within a wider pattern of extensive, frequent violence during specific stages in European prehistory (19). Evidence from the Neolithic indicates that lethal violence and massacres prevailed during periods of population pressure, competition over resources, and/or the expansion of new groups into already-occupied territories (20, 21), a pattern also observed in well-known cases from the New World (22). Neolithic cases of intergroup violence appear to fall into one of two categories, either targeting whole communities (11, 20) or aimed specifically at males from competing groups (21). The former strategy presumably aims at eradicating a competing group from a given territory, whereas in the latter case, it may be assumed that the women and/or children are taken as captives, a practice that is well documented ethnographically and historically for prestate societies (23). Although alternative scenarios (e.g., ritualistic violence or familicide) cannot be ruled out, it seems most plausible that the massacre at Koszyce falls in the former category. The fact that most adult males of the group are missing from the grave most likely reflects that they were away (or fled) when the raid occurred, leaving the remaining group vulnerable. Although it is impossible to identify the culprits of the massacre that took place at Koszyce around 2880–2776 BCE, it is interesting to note that it occurred right around the time when the Corded Ware complex started to spread rapidly across large parts of Central Europe, and it seems plausible that the group from Koszyce fell victim to some violent intergroup conflict related to the territorial expansion of Corded Ware groups or another competing group in the area. If the general interaction between Globular Amphora people and neighboring, steppe-related cultures (including early Corded Ware) was primarily hostile, it would explain why Globular Amphora individuals carry no steppe ancestry and, in part, why Europe experienced such a dramatic reduction in Neolithic genomic ancestry at this time (7, 17). PNAS first published May 6, 2019 |

|

|

|

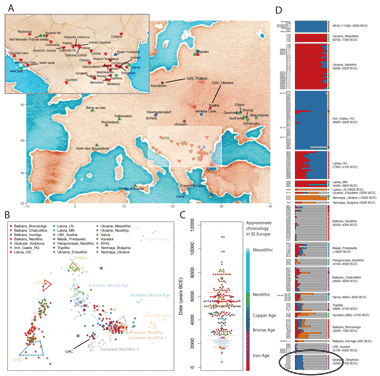

Post by Admin on Jun 3, 2019 18:27:55 GMT

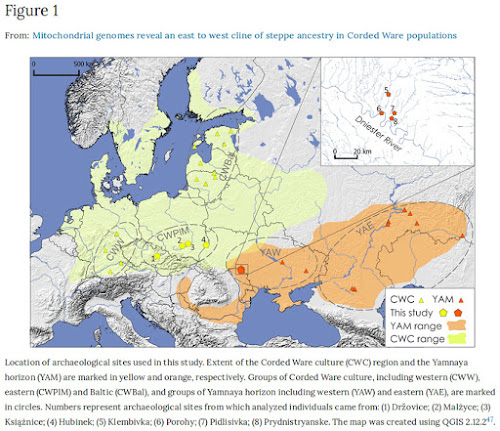

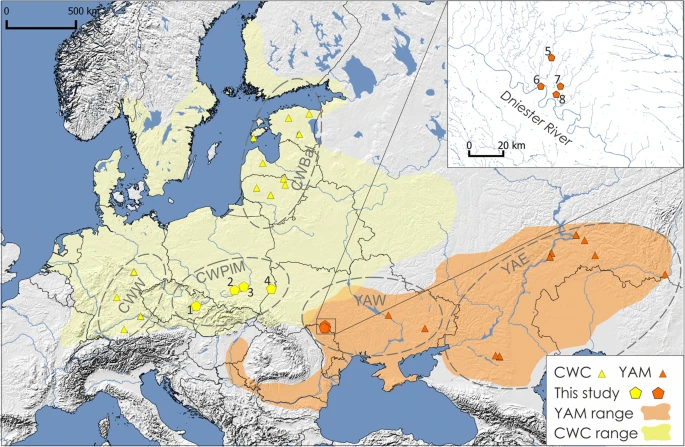

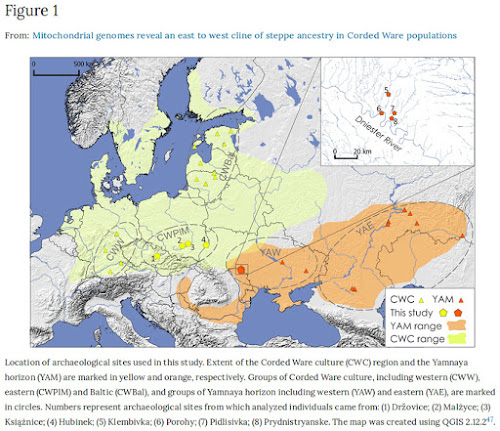

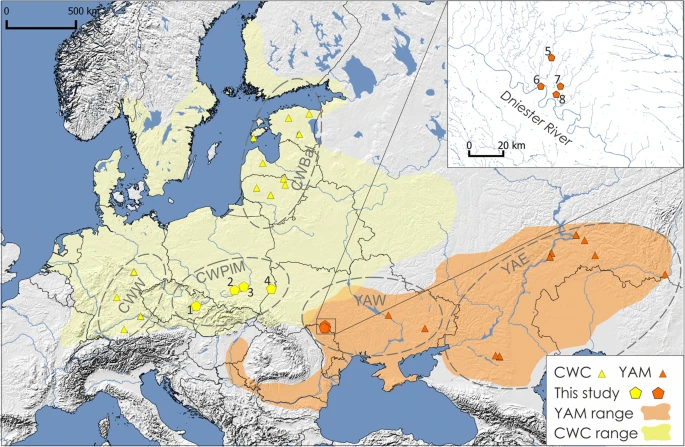

The forest-steppe north-western Pontic region of the middle Dniester and Prut interfluve was a place of contact and exchange routes between human populations inhabiting the drainages of the Black and Baltic Seas from around 4,000 to 2,000 BC1. During this time, the region was occupied by forest-steppe populations attributed to the Eneolithic (3350–3200 BC)1 and the succeeding Bronze Age groups associated with the Yamnaya - Pit Grave (dated to 3,100/3,050–2,800 BC)2, the Catacomb (2,600–2,200 BC), the Babyno (2,200–1,700/1,600 BC) and the Noua (1,600–1,200/1,100 BC) cultures3,4. Although there were cultural differences between these populations, they all shared a similar nomadic lifestyle, pastoral economy and barrow burial rituals5. Some of the rounded burial mounds founded by Eneolithic people were reused by the succeeding cultural entities of the Early Bronze Age1, while other kurgans shared a mix of characteristics from both the Late Eneolithic and the Early Bronze Age funeral rites1,4. According to some researchers6,7,8,9, the Yamnaya culture originated in the Volga-Ural interfluve and spread across the Pontic-Caspian steppe between 3,300–2,800 BC. This cultural expansion led to the development of a less homogenous group of cultural entities belonging to the so-called Yamnaya Cultural-Historical Area/Unity10,11, hereafter reffered to as ‘the Yamnaya horizon’12. People associated with the eastern Yamnaya culture spread across the steppe to the east of Don River. With no settlements identified in this area, they were thought to be more mobile because of their supposed nomadic profile of economy stimulated by environmental conditions of Kuban – North Caspian steppes13. On the other hand, Yamnaya settlements were found more frequently in the forest-steppe Pontic regions, to the west of Don River, probably due to favorable environmental conditions12.  Figure 1 Location of archaeological sites used in this study. Extent of the Corded Ware culture (CWC) region and the Yamnaya horizon (YAM) are marked in yellow and orange, respectively. Groups of Corded Ware culture, including western (CWW), eastern (CWPlM) and Baltic (CWBal), and groups of Yamnaya horizon including western (YAW) and eastern (YAE), are marked in circles. Numbers represent archaeological sites from which analyzed individuals came from: (1) Držovice; (2) Malżyce; (3) Książnice; (4) Hubinek; (5) Klembivka; (6) Porohy; (7) Pidlisivka; (8) Prydnistryanske. The map was created using QGIS 2.12.247. One of the most widely debated issues, which emerged in connection to studies on the Yamnaya horizon, was the relationship between the people associated with the Yamnaya and the Central European final Neolithic cultures, in particular the Corded Ware culture (dated to 2800–2300 BC)14. Archaeological records point to some similarities between the Corded Ware culture and the steppe, including shared practices such as the barrow structures and burial rituals2. Adoption of a herding economy based on mobility through the use of wagons and horses, was also proposed as a common trait associated with both the Yamnaya and Corded Ware cultures12. These observations led some researchers to suggest a possible Yamnaya migration toward the Baltic drainage basin15 or a massive westward expansion of the steppe pastoralist people, representing the “barrow culture”, into the North European Plain12,16. However, specific burial customs of the Yamnaya people, such as the scarcity of grave goods, the presence of ochre, and the building of specific wooden roof or floor structures, generated opposing arguments emphasizing the significant differences between the Corded Ware and steppe cultures2. Recent ancient DNA (aDNA) studies suggest that the large-scale migration of steppe populations associated with the Yamnaya horizon contributed to the formation of the final Neolithic central European populations14,17,18. Moreover, people associated with the Yamnaya horizon have been shown to be an admixed population with ancestry from Eastern hunter-gatherers and Caucasus hunter-gatherers14,17,19,20. Ancient DNA data indicate that the Neolithic populations from Central Europe already had the ‘Caucasus’ genetic component from the eastern steppes around 2,500 BC. Presence of this genetic component was used as an argument for the expansion of people from the Pontic-Caspian region into the central Europe14,17. X chromosome sequence data suggest that it was primarily males who participated in these migrations21,22 and contributed to the formation of the people associated with the Corded Ware culture14,17. Based on the X chromosome data obtained mainly from western Corded Ware-associated individuals, it was estimated that, for every female, ~4–15 males migrated from the steppe21. Subsequently, the Yamnaya genetic component spread across Bronze Age Europe and West Asia14.

Sample ID Region Archaeol. site Archaeol. culture Age of samples Molecular sex MtDNA genome coverage MtDNA haplogroup

poz090 Ukraine Pidlisivka Late Eneolithic 3350–3200 BC XY 6x U2e1a1

poz094 Ukraine Pidlisivka Babyno 2200–1700/1600 BC XX 194x J2b1a

poz211 Ukraine Klembivka Late Eneolithic 2898–2761 BC XY 11x U5a2b

poz213 Ukraine Klembivka Babyno 2117–1950 BC XX 32x J1c2m

poz214 Ukraine Klembivka Late Eneolithic 2863–2630 BC XY 58x H2a1

poz356 Ukraine Klembivka Babyno 1880–1771 BC XX 40x H1e

poz220 Ukraine Prydnistryanske Catacomb 2834–2499 BC XY 27x X4

poz221 Ukraine Prydnistryanske Catacomb 2548–2348 BC XY 114x X4

poz222 Ukraine Prydnistryanske Yamnaya 3023–2911 BC XY 15.6x W3a1

poz225 Ukraine Prydnistryanske Yamnaya 2858–2621 BC n.a. 73x U5a1i1

poz224 Ukraine Prydnistryanske Yamnaya 2847–2574 BC n.a. 97.5x U4c1

poz208 Ukraine Porohy Yamnaya 2882–2698 BC n.a. 42x W3a1a

poz287 Poland Książnice Corded Ware 2400–2300 BC XX 28x H6a

poz286 Poland Książnice Corded Ware 2400–2300 BC XX 19x H15a1

poz256 Moravia Držovice Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC n.a. 71x U4b1a1a

poz257 Moravia Držovice Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC XX 64x I4a

poz235 Poland Hubinek Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC n.a. 5.4x H2a2

poz279 Poland Malżyce Corded Ware 2454–2236 BC n.a. 12x W5b

poz280 Poland Malżyce Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC n.a. 57x W5b

poz281 Poland Malżyce Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC n.a 79x T2e

poz282 Poland Malżyce Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC n.a. 36x U4a2f

poz234 Poland Hubinek Corded Ware 2800–2300 BC n.a. 39x H1e

poz232 Poland Hubinek Corded Ware 3025–2898 BC n.a. 11x U5a1b

Table 1 Description of analyzed individuals. Although questions concerning the migrations of nomadic people have been addressed by a number of studies19,23,24, the contribution of mitochondrial lineages associated with the Yamnaya horizon to the formation of people associated with the Corded Ware culture from the eastern part of the North European Plain, especially from the region of modern Poland, remains contentious. To investigate the maternal relationship between these two groups, we generated complete mitochondrial genomes from the representatives of Late Eneolithic and Early Bronze Age populations from the north-western Pontic region, including Yamnaya groups and individuals associated with the Corded Ware culture from the eastern part of the North European Plain. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jun 4, 2019 18:06:15 GMT

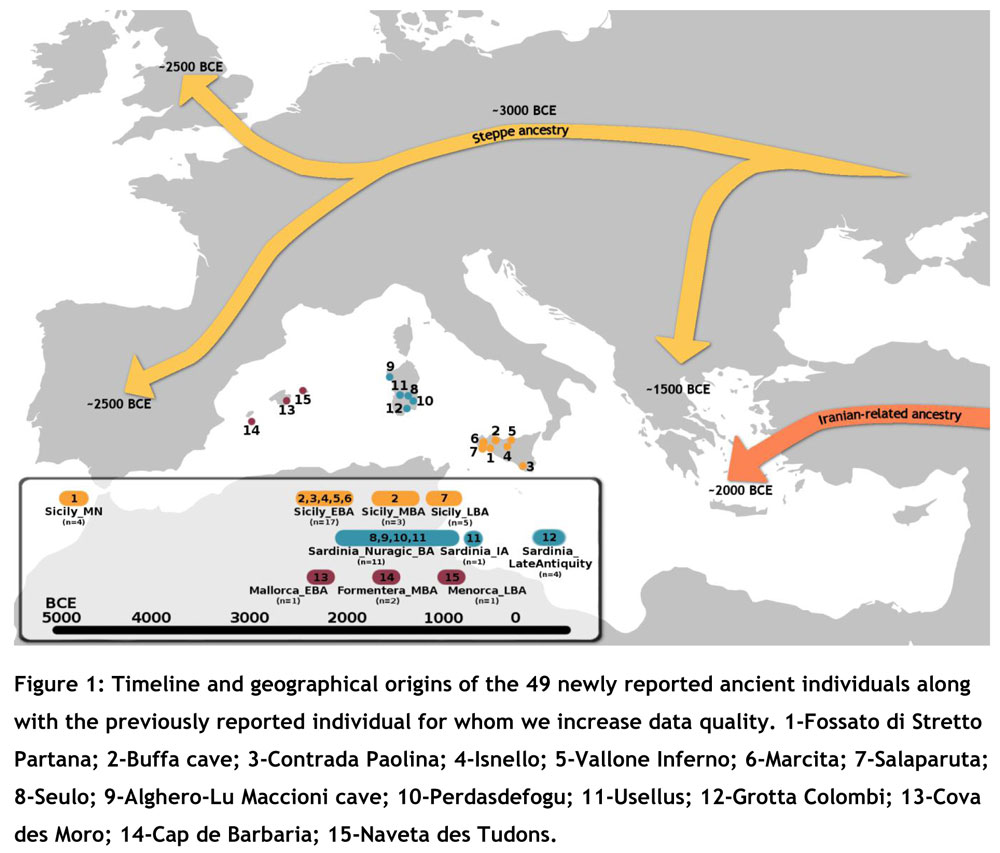

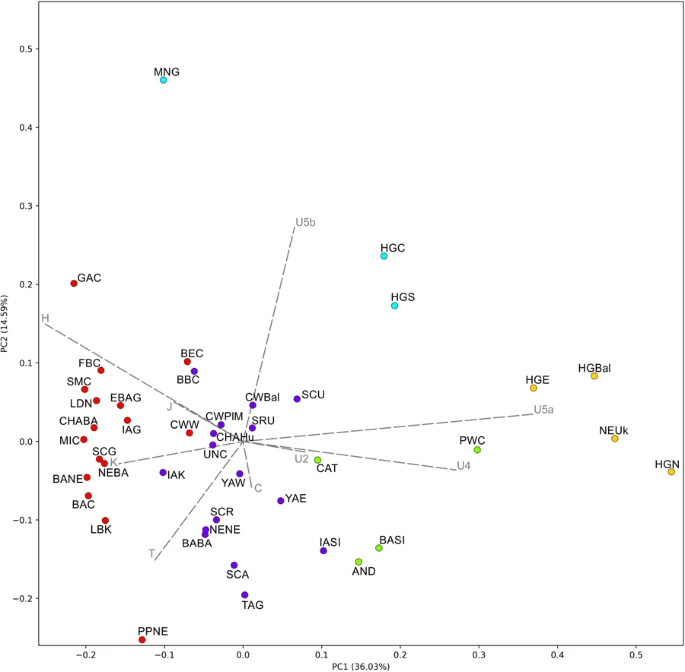

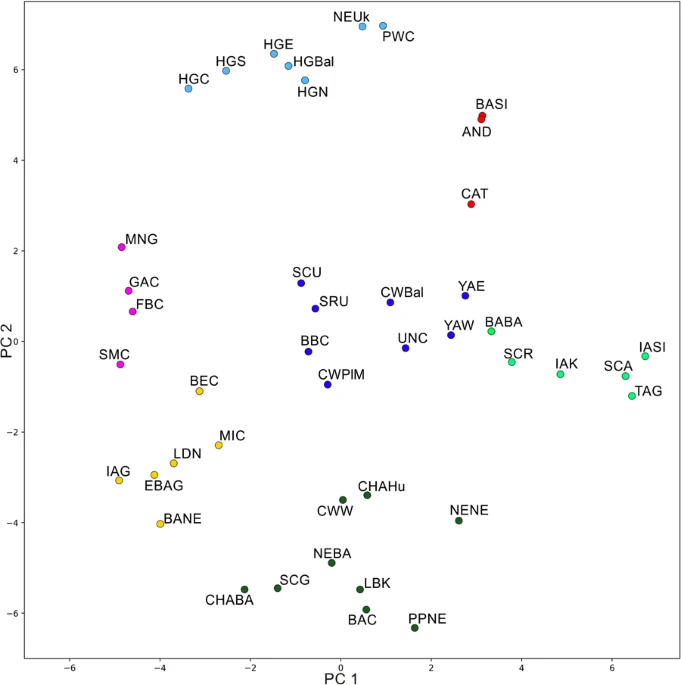

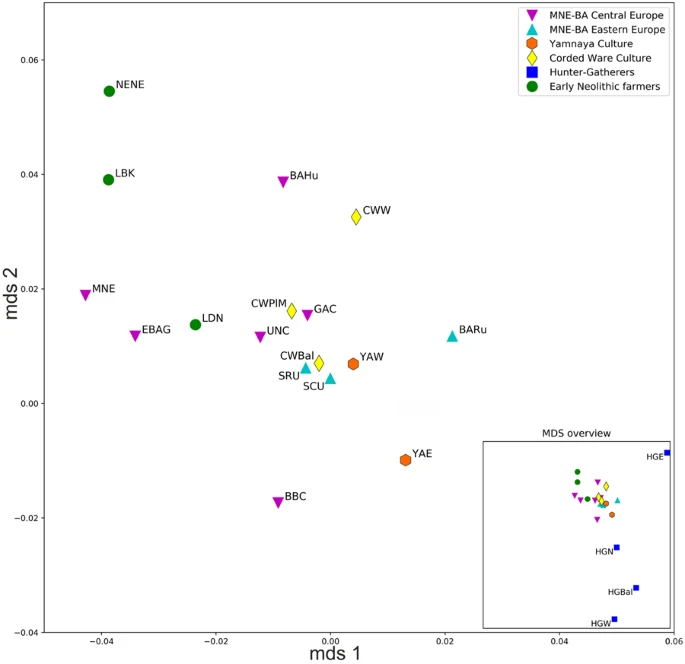

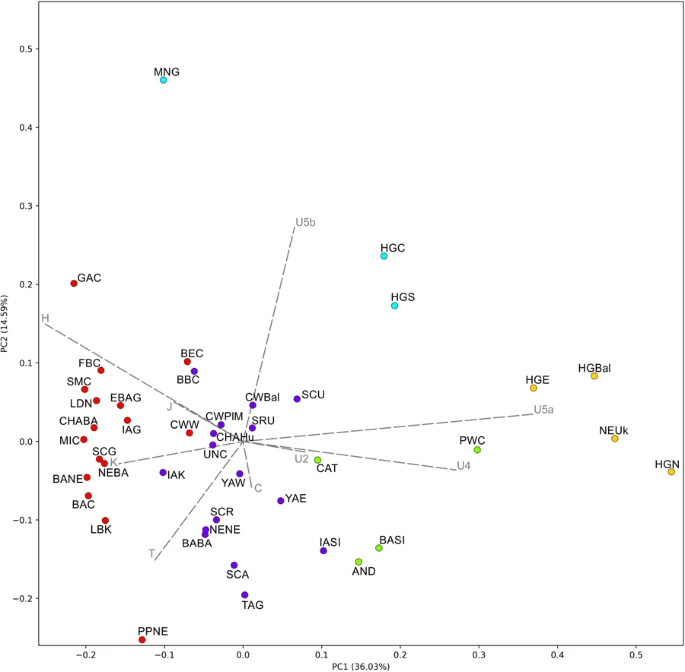

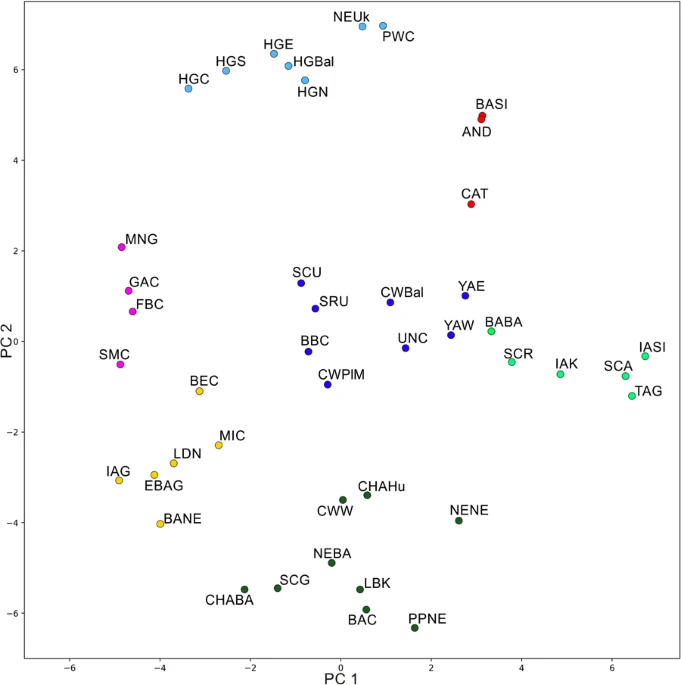

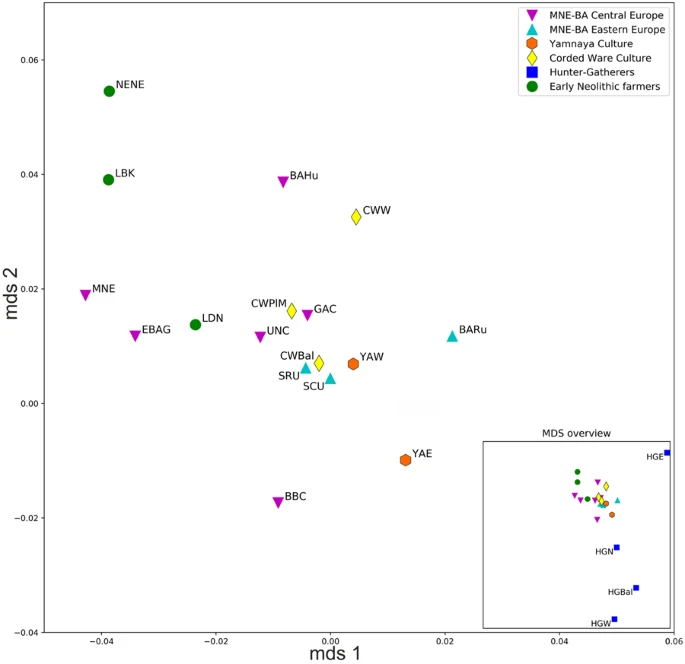

Ancient mitochondrial genomes Out of the 45 analyzed samples, we successfully obtained 23 mtDNA genomes, belonging to individuals associated with the Corded Ware culture (N = 11), and with the Late Eneolithic (N = 3) and Bronze Age (N = 9) from western Pontic region (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Eleven of the mtDNA genomes were retrieved from the Illumina shotgun screening data with the depth-of-coverage (DoC) ranging between ca. 5.4× to 64×. The remaining twelve mtDNA genomes were retrieved from the hybridization capture enrichment followed by PGM Ion Torrent sequencing, and yielded DoC ranging between 11× to 194×. Nucleotide misincorporation patterns assessed using MapDamage showed characteristic aDNA damage involving C-T and G-A transitions at the 5′ and 3′ ends of DNA fragments, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S26). Schmutzi estimations conducted for each individual showed low levels of contaminations (1–3%) (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, we found no contamination in the extraction blanks and PCR negative controls. The mitochondrial DNA data are deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MH176332, MH176333, MH17635-MH176355. In general, the individuals associated with the Corded Ware culture and the Yamnaya horizon were assigned to mtDNA lineages common among modern-day west Eurasian groups (hgs H, I, J, T, U2, U4, U5, W, X). Individuals associated with the Eneolithic and Yamnaya cultures were assigned to hgs U2e1a1, U5a2b, H2a1 and U5a1i1, U4c1, W3a1, W3a1a, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Other Bronze Age individuals from the western Pontic region belonged to hg X4 (two individuals associated with Catacomb culture) and J2b1a, J1c2m, H1e (three individuals associated with Babyno culture). Individuals associated with the Corded Ware culture were assigned to hgs H (H6a, H15a1, H2a2, H1e), U4 (U4b1a1a, U4a2f), W5b, U5a1b, I4a and T2e (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Genetic distances between ancient populations The PCA results described 50.62% of the variability and were combined with the k-means clustering (with the k value of 5 as the best representation of the data, at the average silhouette of 0.2608) (Figs 2 and S27). Based on these results individuals associated with the western and eastern Yamnaya horizon (YAE and YAW in Fig. 2) were grouped within a cluster consisting of populations from central Eurasia and Europe (blue cluster) including people associated with eastern Corded Ware culture (CWPlM) and Baltic Corded Ware culture (CWBal). This cluster did not contain any populations linked with early Neolithic farmers (red), or hunter-gatherers (green and yellow). On the other hand, k-means clustering linked the western Corded Ware culture-associated population (CWW) with Near East and Neolithic farmer ancestry groups from western and central Europe.  Figure 2 The k-means clustering on t-SNE results was consistent with the PCA results, although the approach to dimension reduction of the t-SNE algorithm is completely different than that of the PCA. Scatterplot of populations colored according to the k-means k = 7 (average silhouette 0.5158) (Fig. 3) represented the main components of European genetic ancestry. Individuals associated with western Corded Ware culture (CWW in Fig. 3) clustered with the early Neolithic Farmer ancestry group (dark green), while people associated with CWPlM from this study and CWBal showed greater affinity to the eastern European cluster (dark blue) which included mostly steppe populations associated with the Yamnaya horizon, Srubnaya, and western Scythians. Another clearly defined cluster was the central-western Asia group (red) with Andronovo, Catacomb and Siberian populations. Iron Age central Asia cluster (light green) consisted mostly of Altai and Russian Scythians and populations from Siberia and Kazakhstan. The strong hunter-gatherer ancestry cluster (light blue) included the hunter-gatherers and Neolithic populations with major hunter-gatherers component associated with the Neolithic Ukraine and the Scandinavian Pitted Ware culture. The last two clusters comprised of populations linked with the post-Linear Pottery culture from central Europe and other Middle and Late Neolithic groups from Europe (yellow and purple).  Figure 3 Pairwise mtDNA-based FST54 values (Supplementary Table S4), visualized on MDS using the raw non-linearized FST (stress value = 0.099) (Fig. 4), also supported the PCA results and indicated that western and eastern Yamnaya horizon groups (YAW and YAE) were closer to people associated with the eastern Corded Ware culture (CWPlM) (FST = 0.00; FST = 0.01, respectively; both p > 0.05) and Baltic Corded Ware culture (CWBal) (FST = 0.00; FST = 0.00, respectively; both p > 0.05), than to populations associated with the western Corded Ware culture (CWW) (FST = 0.047 and FST = 0.059, respectively; both statistically significant p < 0.05). Western and eastern Yamnaya horizon groups also showed close genetic affinity to the Iron Age western Scythians (SCU) (FST = 0.0022 and FST = 0.006, respectively, both p > 0.05). The most distant populations to the Yamnaya horizon groups were western hunter-gatherers (HGW) (FST = 0.23 and FST = 0.15, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Table S4).  Figure 4 The FST-based MDS reflected the general European population history in the post-LGM period as the three highest FST scores were detected between western hunter-gatherers (HGW) and people associated with Linear Pottery culture (LBK) (FST = 0.33, p < 0.001), between eastern hunter-gatherers (HGE) and Baltic hunter-gatherers (HGBal) (FST = 0.35, p < 0.05), and between western (HGW) and eastern hunter-gatherers (HGE) (FST = 0.36, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S4). The Yamnaya horizon groups (YAE and YAW) were placed centrally between northern hunter-gatherers (HGN) and Neolithic farmers (LDN), in direct proximity to the Bronze and Iron Age populations from Eastern Europe (SCU, BARu, SRU) and close to individuals associated with eastern and Baltic Corded Ware culture (Fig. 4). We investigated the within- and between-group variability using an AMOVA analysis. Concentrating on the eastern and western Corded Ware groups, we found the best variability distribution when the individuals associated with the western Corded Ware culture (CWW in Supplementary Table S5) were grouped together with the Middle Neolithic/Bronze Age Central Europe groups, while individuals associated with the eastern and Baltic Corded Ware culture (CWPlM, CWBal), and Yamnaya horizon groups (YAW and YAE) clustered together with the eastern Europe populations (from the Middle Neolithic-Bronze Age) (4.68% of variability among groups, 3.04% among populations within groups). |

|