Post by Admin on May 24, 2021 3:39:50 GMT

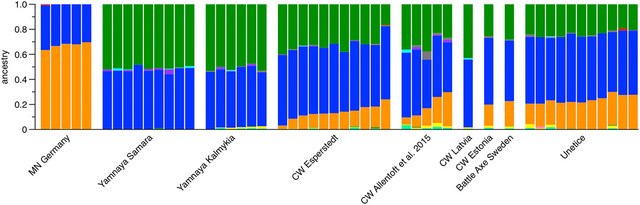

Figure 1. ADMIXTURE plot of select ancient individuals (data from Allentoft et al., 2015; Haak et al., 2015; Mathieson et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2017). CW = Corded Ware; MN = Middle Neolithic.

As Furholt continues his argument, much of his subsequent debate revolves around the term ‘migration’ and (as opposed to) ‘gene flow’ as, for example, when he writes, ‘The argument of Haak et al. (2015) rests on the assumption that the Corded Ware represents a single distinct population and that one would need evidence of Yamnaya affinity in an earlier archaeological culture to make a case for a continuous gene flow. This model seems to exclude the possibility that such a continuous gene flow could take place within the Corded Ware, which lasts for up to 800 years’ (p. 8); and, additionally, ‘the real issue here is that the authors do not make explicit what they mean by the term migration. The suggestion that continuous gene flow would be something different from migration is not consistent with the archaeological debates on the matter’ (p. 8).

I agree that there is no clear definition of migration in our manuscript, which, as the author admits, remains an elusive term. However, the model proposed in Haak et al. is based on the possibility of distinguishing between migration and continuous gene flow, wherein the latter becomes somewhat easier to demarcate. Under the assumption of continuous gene flow between the east (here, the north Pontic steppe) and the west (here, central Europe), we would not expect such a clear distinction between the genetic profiles of both. Instead, we would expect to see a gradient of shared ancestry in which the respective proportions would be maximized on one side (here ‘Early Farmer’ ancestry in the west and ‘Iranian Neolithic’ ancestry in the east), minimized in the opposite direction, but present nonetheless. However, this is not the case, as seen from individuals that span the time frame 8000-3000 bp. Ancestry profiles remain exclusive until the time of the Corded Ware.

Of note, new data from Globular Amphorae-associated individuals from Poland and the Ukraine show no steppe ancestry, that is, they very closely resemble the Middle Neolithic farmers in Figure 1 (Mathieson et al., 2017, available on biorxiv: biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/05/09/135616), which is intriguing given the geographical proximity and contemporaneity with Yamnaya individuals. Likewise, as also seen in Figure 1, one individual associated with the Corded Ware in the Baltic region lacks ‘farmer-ancestry’ (CW Latvia from Jones et al., 2017) and, thus, resembles the steppe ancestry profile of Yamnaya individuals.

Both observations narrow down the remaining time window for the expansion of steppe ancestry into central Europe to a few hundred years at best or perhaps five to ten generations. Given that we do not observe the signal of continuous gene flow over longer time periods (where the formation of steppe ancestry 5000–6000 years ago would pose a time constraint), we were inclined to call this process ‘migration’. Given the time window between the Globular Amphorae individuals with no ancestry and the earliest Corded Ware individuals with very large proportions, this process is still considered ‘rapid’ in biological terms and ‘massive’ in comparison.

As a further consideration, Furholt argues that, ‘this interpretation of the patterns seems to overstate the explanatory powers of the PCA. The notion of a generally closer connection of Corded Ware individuals to Yamnaya individuals than the other Late Neolithic samples is much less clear in a different study using different samples connected to Corded Ware (Allentoft et al., 2015)’ (p. 8). PCA and ADMIXTURE are qualitative methods that are used to characterize the ancestry profiles of prehistoric individuals. All observations from PCA and ADMIXTURE are backed by formal statistics (f- and D-statistic, etc.), which are quantitative methods and which were described in detail in the respective papers. As such, formal admixture tests were carried out to explain the genetic profiles of Corded Ware-associated individuals and the likely source populations (e.g. Haak et al., 2015: Supplementary Information 7, page 75 onwards and Supplementary Information 9, page 101 onwards). The observed ancestry components as well as the positioning of Corded Ware individuals in principal component space are reliable and remain stable in all subsequent studies, which include these datapoints (e.g. Günther & Jakobsson, 2016; Jones et al., 2017; Mittnik et al. 2017, biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/03/03/113241; Saag et al., 2017).

Finally, I would like to address Furholt's statement that ‘for example, in their Supplementary Information 2, Haak et al. (2015) demonstrate that three individuals connected to the Pitted Ware culture in Sweden (taken from Skoglund et al., 2012) are clearly under that eastern genetic influence’ (p. 10). Supplementary Information 2 describes the mitochondrial DNA data. Individuals associated with the Pitted Ware show high proportions of mtDNA U4 and U5 lineages (~74%), which are very common among all Holocene hunter-gatherer individuals reported so far. This mtDNA profile thus equates to the blue component of the autosomal data and not to ‘steppe ancestry’ per se.

Overall, I welcome this opportunity of interaction and open discussion. It is important that archaeologists shed a critical light on the recent findings of archaeogenetics in order to put these into a balanced and well-contextualized perspective. Likewise, I am grateful for the opportunity to clarify a few technical aspects of our genetic work, which might relativize some of Furholt's arguments.

As Furholt continues his argument, much of his subsequent debate revolves around the term ‘migration’ and (as opposed to) ‘gene flow’ as, for example, when he writes, ‘The argument of Haak et al. (2015) rests on the assumption that the Corded Ware represents a single distinct population and that one would need evidence of Yamnaya affinity in an earlier archaeological culture to make a case for a continuous gene flow. This model seems to exclude the possibility that such a continuous gene flow could take place within the Corded Ware, which lasts for up to 800 years’ (p. 8); and, additionally, ‘the real issue here is that the authors do not make explicit what they mean by the term migration. The suggestion that continuous gene flow would be something different from migration is not consistent with the archaeological debates on the matter’ (p. 8).

I agree that there is no clear definition of migration in our manuscript, which, as the author admits, remains an elusive term. However, the model proposed in Haak et al. is based on the possibility of distinguishing between migration and continuous gene flow, wherein the latter becomes somewhat easier to demarcate. Under the assumption of continuous gene flow between the east (here, the north Pontic steppe) and the west (here, central Europe), we would not expect such a clear distinction between the genetic profiles of both. Instead, we would expect to see a gradient of shared ancestry in which the respective proportions would be maximized on one side (here ‘Early Farmer’ ancestry in the west and ‘Iranian Neolithic’ ancestry in the east), minimized in the opposite direction, but present nonetheless. However, this is not the case, as seen from individuals that span the time frame 8000-3000 bp. Ancestry profiles remain exclusive until the time of the Corded Ware.

Of note, new data from Globular Amphorae-associated individuals from Poland and the Ukraine show no steppe ancestry, that is, they very closely resemble the Middle Neolithic farmers in Figure 1 (Mathieson et al., 2017, available on biorxiv: biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/05/09/135616), which is intriguing given the geographical proximity and contemporaneity with Yamnaya individuals. Likewise, as also seen in Figure 1, one individual associated with the Corded Ware in the Baltic region lacks ‘farmer-ancestry’ (CW Latvia from Jones et al., 2017) and, thus, resembles the steppe ancestry profile of Yamnaya individuals.

Both observations narrow down the remaining time window for the expansion of steppe ancestry into central Europe to a few hundred years at best or perhaps five to ten generations. Given that we do not observe the signal of continuous gene flow over longer time periods (where the formation of steppe ancestry 5000–6000 years ago would pose a time constraint), we were inclined to call this process ‘migration’. Given the time window between the Globular Amphorae individuals with no ancestry and the earliest Corded Ware individuals with very large proportions, this process is still considered ‘rapid’ in biological terms and ‘massive’ in comparison.

As a further consideration, Furholt argues that, ‘this interpretation of the patterns seems to overstate the explanatory powers of the PCA. The notion of a generally closer connection of Corded Ware individuals to Yamnaya individuals than the other Late Neolithic samples is much less clear in a different study using different samples connected to Corded Ware (Allentoft et al., 2015)’ (p. 8). PCA and ADMIXTURE are qualitative methods that are used to characterize the ancestry profiles of prehistoric individuals. All observations from PCA and ADMIXTURE are backed by formal statistics (f- and D-statistic, etc.), which are quantitative methods and which were described in detail in the respective papers. As such, formal admixture tests were carried out to explain the genetic profiles of Corded Ware-associated individuals and the likely source populations (e.g. Haak et al., 2015: Supplementary Information 7, page 75 onwards and Supplementary Information 9, page 101 onwards). The observed ancestry components as well as the positioning of Corded Ware individuals in principal component space are reliable and remain stable in all subsequent studies, which include these datapoints (e.g. Günther & Jakobsson, 2016; Jones et al., 2017; Mittnik et al. 2017, biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/03/03/113241; Saag et al., 2017).

Finally, I would like to address Furholt's statement that ‘for example, in their Supplementary Information 2, Haak et al. (2015) demonstrate that three individuals connected to the Pitted Ware culture in Sweden (taken from Skoglund et al., 2012) are clearly under that eastern genetic influence’ (p. 10). Supplementary Information 2 describes the mitochondrial DNA data. Individuals associated with the Pitted Ware show high proportions of mtDNA U4 and U5 lineages (~74%), which are very common among all Holocene hunter-gatherer individuals reported so far. This mtDNA profile thus equates to the blue component of the autosomal data and not to ‘steppe ancestry’ per se.

Overall, I welcome this opportunity of interaction and open discussion. It is important that archaeologists shed a critical light on the recent findings of archaeogenetics in order to put these into a balanced and well-contextualized perspective. Likewise, I am grateful for the opportunity to clarify a few technical aspects of our genetic work, which might relativize some of Furholt's arguments.