|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 9, 2021 22:39:03 GMT

One explanation for a connection between the Jōmon and coastal East Asians could be that the Jōmon were not completely isolated from mainland East Asians. By 3900 years ago, the date of the oldest Jōmon nuclear genome sampled (from Funadomari, Figure 1), Austronesians were rapidly expanding into islands in the Pacific (Tsang, 1992; Spriggs, 2011). The main patterns observed both in past mtDNA studies and in recent genome-wide studies of the Jōmon all seem to highlight coastal connections, which may suggest that the Jōmon experienced gene flow with populations deriving from mainland East Asia prior to any contact associated with migration of Mumun immigrants from the Korean peninsula. This is supported by archaeological studies that track artefact commonalities resulting from trade and contact along the coast (Bausch, 2017), some of which date back to the Palaeolithic (Morisaki, 2015). This is logical given that the Jōmon were inveterate deep-sea fishers given their harpoon technology, and scores of dugout canoes have been excavated from archaeological sites (Habu, 2010) — although it is not clear how seaworthy they were.

To address the relationship between population movement and the spread of farming in the Japanese archipelago, Jōmon and Mumun ancestry must be well characterized. Here in this section, we have briefly highlighted some key features of Jōmon ancestry using ancient mtDNA and nuclear genomes. First, Jōmon ancestry diverged fairly early from that of mainland East Asians. Second, they do not show notable connections to currently sampled basal Asians, such as the Tianyuan individual or Hòabìnhians. Third, they share coastal connections with coastal populations in northern and southern East Asia. This suggests that one of the major assumptions about the Jōmon may not be true – that they were genetically isolated since the first Palaeolithic migrations to the Japanese archipelago until the Mumun migration at the end of the Jōmon period. If the Jōmon themselves are already partially admixed, then characterizing increased gene flow from the mainland in populations from the Yayoi or more recent historic periods will be substantially more complex.

Advances that utilize rare alleles or long haplotypes (Lawson & Falush, 2012; Schiffels et al., 2016) are increasing the power of demographic analyses focused on more closely related populations, including in Japan (Takeuchi et al., 2017), but these are still difficult to apply in the realm of ancient DNA where obtaining data with high enough coverage is still rare. Present-day genomes are informative on recent history (Takeuchi et al., 2017) but make it difficult to resolve questions about periods as early as the Yayoi. Ancient genomes directly from the Yayoi are needed to clarify early population movement associated with the spread of farming. Such sampling is just starting, where two nuclear genomes from the Shimo-Motoyama rock shelter site in northwest Kyushu dating to the Terminal Yayoi show evidence of admixture between Jōmon- and mainland East Asian-related ancestry, in a region where populations were thought to be of unadmixed Jōmon-lineage (Shinoda et al., 2019). Characterizing the role admixture played during the Yayoi requires understanding of the features of Jōmon ancestry described above to help us understand how to contextualize these and future data.

The remaining parts of this paper focus on populations in the Yayoi to Nara periods, examining (1) how archaeological shifts indicate a complex role for migration and admixture that was probably region-specific and (2) how similarities in dialect types hint at prehistoric migration of admixed Yayoi populations along the Japan Sea coast, which only stresses the need for more data on ancient Yayoi DNA.

The coastal genetic connections proposed are not directly tied to the farmer/language spread hypothesis because they are found in the Jōmon and thus would be prior to the spread of farming. Instead, they are a cautionary point – to understand farmer/language spread, we need to understand who were the pre-existing populations (the Jōmon). If their ancestry is not as genetically isolated as has been argued, then future studies need to account for that.

|

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 10, 2021 21:25:54 GMT

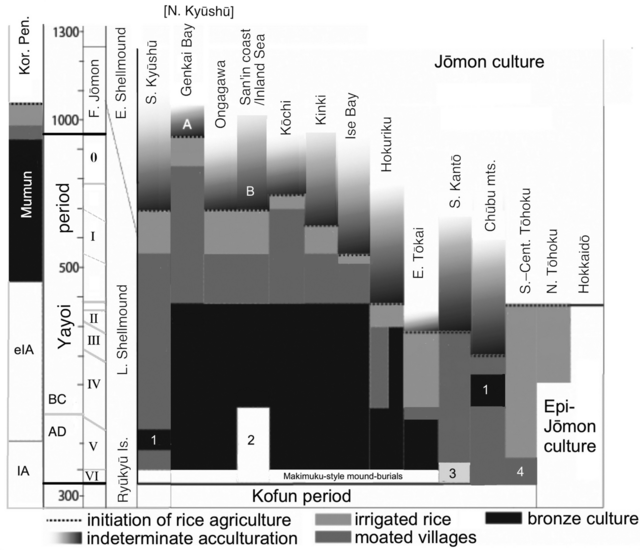

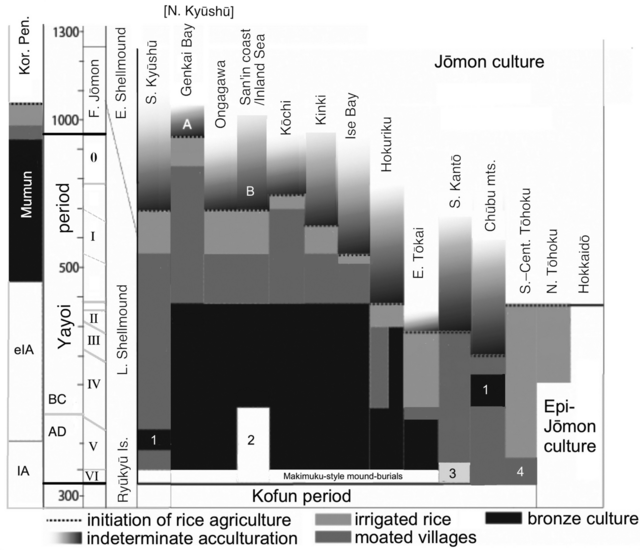

Agricultural transition in Japan In dealing with this problem, first we must define ‘agriculture’. This is not as easy as it appears, since the Jōmon were experienced at plant management, leading to several local domesticated species. Thus, they can be called hunter–gatherer–fisher–horticulturalists. However, the plants that they domesticated or at least managed – soybeans, adzuki, Perilla, sweet chestnuts and Japanese millet (Echinochloa utilis) among others – were not suitable for intensive cultivation as carbohydrate sources to become staples (Crawford, 2011; Barnes, 2015: 111–112, and references therein). Crawford would rather discard the distinction between horticulture and agriculture, preferring to deal with proportionalities in ‘resource production’, which includes not only food but other strategic resources such as lacquer and hemp for fibres. Here, we use ‘agriculture’ to refer to the farming of major starch-grain crops: rice (Oryza sativa) and millets (Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum) in Early Yayoi, with barley and wheat added in later Yayoi. The Jōmon subsistence system was interrupted by the importation of rice and millets from the Korean Peninsula in the Mumun Period, heralding the start of the Yayoi period in the Japanese Islands. The beginnings of rice agriculture in each region of Japan have been meticulously tracked, first from its source on the continent into North Kyushu (Miyamoto, 2017, 2018, 2019) and then eastwards through the archipelago (Fujio, 2004, 2009, 2013, 2014, 2017). Proto-Japanese speaking Mumun migrants (Whitman, 2011) coming into North Kyushu interacted with Jōmon peoples there, creating an initial admixed Yayoi population which then spread throughout the Japanese islands as they occupied new lands for farming. For each region, Fujio has identified a ‘hazy’ period of possible cultivation capped by the clear introduction of rice agriculture (Figure 3); he distinguishes this hazy period, however, from the clear adoption of irrigated rice agriculture and the appearance of the continental cultivation toolkit, moated settlements and moated burials. These elements have been treated as the ‘Yayoi package’ (Mizoguchi, 2013) or ‘Yayoi complex’ (Miyamoto, 2016, 2019). Within most of western Honshu Island, Fujio expects that grain cultivation (rice and particularly millets) preceded the formal package. If we assume that the package was instituted by migrating farmers, the hazy periods and non-irrigated rice-farming periods could represent the gradual conversion of Jōmon-lineage peoples to an agricultural way of life. By 380 BC, however, the ‘Yayoi package’ entailing bronze and iron usage was fully established west of the ‘Waist of Honshu’ (between Wakasa Bay and Ise Bay, Figure 1).  Figure 3. Regional interfaces of expanding agriculture and Jōmon lifeways through phases I–V of the Yayoi period, set against the Mumun and Iron Age periods of the Korean Peninsula and the Shellmound periods of the Ryūkyū Islands. Source: Fujio (2013), fig. 3, modified by GLB with permission. Key: 1, instances of bronze introduction and then rejection; 2, abandonment of bronze ritual use; 3, use of bronze bells; 4, moated burials but not moated villages. Beyond the Waist of Honshu, the uptake of farming was far more diverse. Current research identifies phases of Jōmon pottery usage during the advent of agriculture in the Kinai, Chūbu central mountains, and Kantō regions where cultivation of dry-field crops also preceded irrigated rice agriculture (Shitara & Takashe, 2014; Shitara & Fujio, 2014, pp. 12–13; Takase, 2014; Barnes, 2019). Thus, some farmers in the Yayoi period might have been neither genetically admixed with Mumun (being Jōmon-lineage) nor Japanese speakers. Rice agriculture was established in Hokuriku and Tōhoku from 380 BC. However, settlements at the northern tip of Honshu failed by 100 BC, with occupants reverting to a hunting and gathering lifestyle. Thus, North Tōhoku is included with Hokkaido in the Epi-Jōmon period, which lasted to 700 AD, but we will refer to Jōmon-lineage people in other parts of Tōhoku also as Epi-Jōmon. According to Figure 3, irrigated rice agriculture was instituted by 380 BC in Hokuriku and 300 BC in South Kantō, but not until 220 BC in Chūbu and 50 BC in eastern Tōkai. Interestingly, it reached North and South Kantō via different routes. The specific ceramic style accompanying the introduction of rice into Gunma Prefecture in northwest Kantō had its origin near the Japan Sea coast in Niigata Prefecture (Baba, 2008). It most likely arrived there through diffusion along the Japan Sea coast from western Honshu, a completely different route from that arriving in Kanagawa Prefecture along the Pacific seaboard. North of the Toné River, the essential elements of the Yayoi ‘package’ are mainly missing until ca. 150 AD (Fujio, 2013). Thus, it is assumed that cultivation techniques for rice and millet in South and Central Tōhoku were previously borrowed by Epi-Jōmon peoples living in this area and the Japanese language was spread by later movements of people in the Kofun period. In the second and third centuries AD, state formation processes began with the widespread adoption of mounded tomb building for those Yayoi elites who had risen to high status within the developing agricultural polities. The succeeding Kofun (‘old tomb’) period (Barnes, 2007) witnessed the establishment of a centralized Yamato state in the fifth-century Kinai region. This was also a century of a second wave of immigration from the Korean Peninsula, stimulated by warfare among Peninsular states. In the fifth and sixth centuries, migrations of elites from western Honshu augmented the Kantō population and introduced equestrian culture. The Nara period began when a national capital, Heijō (Figure 1), was built in today's Nara Prefecture. At this point, however, the Yamato state was limited to the Kinai region, but alliances were made with outlying chieftains in Kyushu and Kantō. By the mid-seventh century these figures were integrated into a court hierarchy that represented an expanded Yamato state. However, this state did not extend further north than Kantō; peoples who occupied the Tōhoku region were beginning to be called emishi in court documents. The Nara state actively pursued military activities to bring this region under court control, although they ultimately failed and the region remained under the rule of prominent emishi. ‘Emishi’ in the Nara period is understood to have been a word that designated people who lived in the north beyond the reach of the state. It was neither an ethnonym nor referred to a way of life but was an administrative term – and so encompassed everyone living beyond state jurisdiction regardless of subsistence, language, or genetic background. We assume that those emishi who practised rice agriculture spoke Japanese, but Ainu place names surviving from Niigata and Fukushima northwards clearly indicate that the Ainu language was being spoken by some emishi (see Hudson, 1994, fig. 1). Historical documents record the need for interpreters at least once during the state expansion into the north (the Emishi Wars 774–811), which ended abruptly with the court abandoning its military campaigns (Friday, 1997); the Epi-Jōmon included among the emishi were very likely speakers of an Ainu-related language, and most linguists view Ainu as a relic Jōmon language. It is clear that evidence of the Ainu language predates the emergence of the Ainu people in historical documents in the seventeenth century (Hudson, 1999). Knowledge of the subsistence system of Tōhoku in the Kofun and Nara periods is not well developed. The Kantō became a prominent horse-breeding area, supplying the Court with horses and cavalry, leading to the development of the medieval samurai (Farris, 1992; Friday, 1997). Further north, Epi-Jōmon, admixed Yayoi descendents and Kofun-period pioneers formed the emishi who opposed the Nara Court's efforts at subjugation. By the ninth century, powerful local warlords from southwestern clans such as the Abe and Kiyohara ruled large territories in the north on behalf of the Heian Court, and finally in the twelfth century, the Northern Fujiwara established their rule over Tōhoku. It is significant that, despite the court origins of this family, the coffins of the first three Northern Fujiwara rulers contained only a little rice and no continental millets, but large quantities of barnyard millet (E. utilis) (Hudson, 1999, p. 76). This suggests that continental-type agriculture was not a prominent feature of Tōhoku farming even into the Medieval period, with barnyard millet harking back to Jōmon horticultural practices. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 11, 2021 4:30:23 GMT

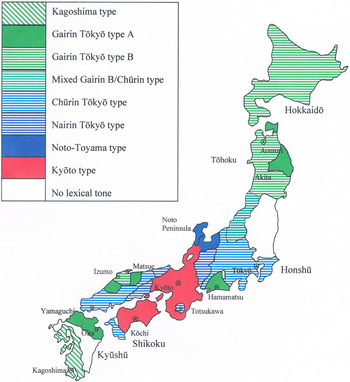

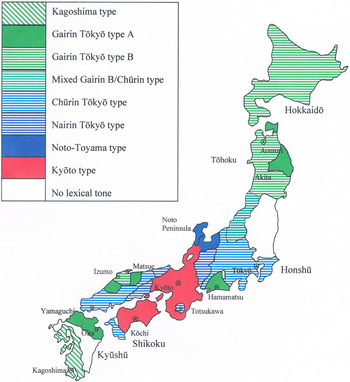

The languages of Japan As in many other areas of the world, migrations in connection with the spread of agriculture in Japan are thought to have led to large-scale replacement of the languages of indigenous hunter–gatherers (Robbeets & Savelyev, 2017). The only remnant today of the many languages of hunter–gatherers that must have been present in Japan in the Jōmon period is formed by Ainu, an (almost) extinct language on the northeastern island of Hokkaidō. The presence of Ainu place names in Honshū, from Niigata and Fukushima Prefectures northwards, indicates that this region too was once an area where an Ainu-related language was spoken. All other languages in the archipelago now belong to the Japanese language family. It is likely that at least initially diversification in the language was low, as is often the case when a group of migrants spreads out over a new territory. Dialect borders that later developed in Japan often follow natural barriers such as mountain ranges that impede communication between neighbouring areas. The best-known dialect border for instance, which divides the dialects up into an eastern Japanese and a western Japanese dialect group based on differences in vocabulary and grammar, follows the Hida and Kiso mountain ranges in central Honshū. Most of these differences, for instance those in grammar, do not go back further than the fourteenth century, and many are linked to linguistic influence radiating out from the old capitals of Nara and Kyōto. Some other dialect borders, on the other hand, may have links to the prehistoric migrations that spread agriculture through the islands. The unexpected dialect type of the northeast An example of such an unexpected dialect distribution is the fact that the phonology and tone system of the Tōhoku dialect resemble those of Izumo, on the Japan Sea coast in the west of Honshū, more than those of the adjacent Kantō region. The tone system of West Kantō, for instance, belongs to the so-called Chūrin or ‘middle circle’ type, in which the division of the words of the language in tone classes is different from that of the Tōhoku region, which has a so-called Gairin or ‘outer circle’ type tone system. These names are derived from the geographical positions of the types relative to each other (Figure 4). An earlier work (De Boer, 2010) analysed the Gairin-type merger pattern of the proto-Japanese tone classes as the result of an innovation that other dialects lacked. As such, a Gairin-type system can develop multiple times independently, as the tonal assimilations that gave rise to the Gairin system are natural (there are, for instance, also two regions with Gairin A tone systems in Kyūshū and Shizuoka), but the agreements between the dialects of Izumo and Tōhoku go deeper.  Figure 4. Map of the Japanese tone systems. Adapted by EdB from Wurm and Hattori (1981): no page number. Within the innovative Gairin type, a further innovation occurred, resulting in a sub-type where high tone shifts away from syllables that contain /i/ or /u/. It can be seen that this type (Gairin B in Figure 4) developed in Izumo in the centre of the region, whereas the older Gairin type (Gairin A) was preserved in the periphery. The Gairin B innovation is also found in the Tōhoku region, except in two areas far removed from the Japan Sea coast. This distribution suggests that the Gairin B innovation was introduced on the Japan Sea coast side, and spread eastward from there. The vowel systems of both Izumo and Tōhoku have centralized /i/ and /u/ and raised /e/ and /o/ so that these vowels are all close together and no longer maximally opposed to each other as they are in other Japanese dialects. In central Izumo and in the Tōhoku region (except for a small area far removed from the Japan Sea coast), this has resulted in mergers between vowels (Figure 5). This geographical distribution, too, suggests that an innovation that originated in Izumo was introduced to the northeast by way of the Japan Sea coast. The East Kantō dialect (Figure S2) takes a somewhat intermediate position between the West Kantō dialect and the Tōhoku dialect. Some centralization of /i/ and /u/ is present, and the fact that the tonal distinctions have disappeared is most likely the result of a mixture of West Kantō (Chūrin) and Tōhoku (Gairin) influences. From other areas in Japan it is known that confusion between adjacent tone systems with different merger patterns of the tone classes can lead to collapse of the system. The northeastern toneless zone includes not only the East Kantō dialect, but also the Pacific side of southern Tōhoku (Figure 4). On the Japan Sea side of southern Tōhoku the reflexes are mixed Chūrin and Gairin B, but the system has not collapsed. What does the opposition between the West Kantō tone and vowel system and the northern Tōhoku tone and vowel system and the intermediate zone between them mean for the way in which the northeast was settled by Japanese-speaking farmers? There are a number of things to consider. Vocabulary can be easily borrowed long distance from other dialects, as long as there is contact (for instance through trade along the coast). Phonology, or the sound structure of a language, on the other hand, usually spreads to adjacent areas, with which there is sustained contact. If it spreads to distant areas, migration is the most likely cause, although it is possible for similarities in phonology between far-flung regions to be the result of parallel independent development, if the innovations are easily repeatable and cross-linguistically common. The similarities between Izumo and Tōhoku (and to a lesser extent the Noto Peninsula) come in shared sets (see Tables S1 and S2; and De Boer, forthcoming), which makes parallel independent development unlikely. It suggests movement of people along the coast in at least two different periods: first from Izumo to the area of the Noto peninsula (present-day Ishikawa and Toyama Prefectures), spreading the set of features listed in Table S1; and later from Izumo to the Tōhoku coast, spreading the set of features listed in Table S2. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Aug 11, 2021 20:56:37 GMT

Izumo in the Late Yayoi period Although Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) is nowadays relatively poor and sparsely populated, this was not always the case. Izumo was one of the most powerful confederacies of the Mid and Late Yayoi periods. It was the great rival of Yamato and the focal point of a wide maritime trade network that included the Japan Sea coast, the Ryūkyūs, Kyushu, Korea and China (Torrance, 2016). Izumo formed alliances with other adjacent regions along the Japan Sea coast; Watanabe (1995) speaks of an ‘Izumo cultural zone’ which he places in the Late Yayoi period. The corner-projected mound burials typical for Izumo in this period are also found on the Noto Peninsula and in Toyama Prefecture, where they stem from 100–250 AD (Maeda, 2007, p. 6). This makes it likely that the presence of the Izumo vowel system on the Noto Peninsula and in Toyama dates back to the Mid to Late Yayoi period, suggested not only by the congruence of burial types (Figure S3) but also the presence of the Izumo-style vowel mergers in Toyama (Figure 5). The Izumo-style tone systems (Gairin A and Gairin B) had apparently not yet developed, as the tone system of the Noto Peninsula does not share these innovations (Figure 4). Some other innovations have occurred in the local tone systems since then, but not the same as those shared by Izumo and Tōhoku. The fact that the Izumo tonal innovations are today present in the northern Tōhoku region, and in a mixed form along the southwestern Tōhoku coast, means that migrations from Izumo to these areas must have taken place after the Gairin B innovations developed. The presence of both Gairin A and Gairin B in the northeast may indicate migrations in different periods. It may also be related to different points of departure from Izumo, as political and economic prominence in Izumo fluctuated historically between the eastern and western parts (Piggott, 1989; Torrance, 2016). The Gairin B tonal innovation is most advanced in western Izumo (Hirako, 2017), meaning that it most likely started there and only gradually spread to eastern Izumo. In the Tōhoku region too, the Gairin B system was most likely present in a smaller area in earlier times. The tone shifts typical of this system continue to spread to adjacent areas: recent fieldwork (Boiko, 2018) has shown that, by now, the Gairin A area on the Shimokita Peninsula has disappeared, and instead, the Gairin B tone shifts have been adopted. Looking for the time of the migrations Exploring the similarity of the Izumo and Tōhoku dialects, it is necessary to examine opportunities for migration of Izumo dialect speakers into the northeast. Although the very first forays of rice farmers from western Japan to the northern tip of Honshū already took place in the Middle Yayoi period, these settlements were later abandoned. The full ‘Yayoi package’ reached the coastal areas of Ishikawa, Toyama and western Niigata as early as 300 BC. It is possible that rice farmers settling along the coast departed from Izumo, but there is no direct evidence for this. Clear evidence of influence from Izumo is more recent: the Izumo-style corner-projected burial mounds in Ishikawa and Toyama date from 100–250 AD. While the full Yayoi ‘package’ appeared briefly in the central mountains (Figure 3: #1, Chūbu district), it also intruded into western Gunma Prefecture at this time. The ceramics accompanying the irrigated-rice culture package derived from the Jōetsu Basin in western Niigata and spread through the river valleys of Nagano Prefecture into western Gunma (Baba, 2008). It is unlikely that the rice farmers who moved inland from western Niigata spoke a dialect with the features typical of Izumo. Linguistic influence from Izumo in the form of migration was not only later, it also may have been initially limited to Ishikawa (i.e. the Noto Peninsula) and Toyama, as Izumo-style mound burials have not been found in Niigata. If there was already some Izumo influence on the dialect of Niigata at the time when rice farmers moved inland to Gunma, it would have been on the vowel system only. The tonal innovations in the Izumo dialect had not yet occurred, judging from the fact that these are not present in the dialects of Ishikawa and Toyama. What applies to the dialect of Niigata also applies to Nagano (Chūbu) and Gunma (West Kantō), which was settled from Niigata, and to Tochigi and Ibaraki (East Kantō), which were all settled overland. If the Tōhoku region was entirely settled overland from these areas, the similarities with the Izumo dialect remain unexplained. Can migration of Izumo dialect speakers into Tōhoku in later periods explain the similarities between the dialects? Piggott (1989) examined the history of Izumo throughout the Late Yayoi and Kofun periods, distinguishing between eastern and western Izumo. Izumo's unique mound-burial culture of Late Yayoi gave way to cultural and political inroads from Kibi to the south and Yamato itself, first into western Izumo. The chieftains of eastern Izumo maintained trade relations with northern Koshi (western Niigata) into the sixth century, but by the 540s the Izumo chieftains had all allied with Yamato (Piggott, 1989, pp. 59–60). Torrance (2016, p. 4), on the other hand, argues that Izumo remained an important and independent presence along the Japan Sea coast, at least until the late sixth or early seventh century. Under the circumstances it is possible that groups from Izumo, avoiding Yamato pressure, would migrate northward along the Japan Sea coast. Diffusion into Tōhoku through mountain basins and over passes could have taken place, but were the numbers enough for linguistic change throughout Tōhoku? The mixed nature (and collapse) of the tone systems in south and central Tōhoku suggest that there was some influence but not enough to determine the dialect. The linguistic influence in northern Tōhoku, however, was much stronger. Hudson (2017) mentions that until the fifth century the pottery types of the northern Tōhoku region and Hokkaidō were identical. From the fifth to the seventh centuries, however, this pottery type starts to disappear from northern Tōhoku, and is from then on restricted to Hokkaidō only. This development has been taken to mean that the Epi-Jōmon population among the emishi who, from the evidence of place-names, must have spoken an Ainu-related language, moved away from northern Honshū into Hokkaidō in that period. According to Matsumoto (2018, p. 158), after the late fifth century there are no traces of habitation in the northern Tōhoku for about a century, after which a new population arrives in the late sixth century. The new arrivals were archeologically indistinguishable from Kofun cultures elsewhere in Japan (Matsumoto, 2018, p. 159). If the people arriving in the late sixth century were from Izumo, then northern Tōhoku would have been sparsely populated at that time, as the Epi-Jōmon population had for a large part moved away. That means that the new population could rapidly spread out over the entire area, which would explain why the Izumo-style tone system was preserved well there, in contrast to the situation in south and central Tōhoku. In south and central Tōhoku there was interference not only from other dialects but most likely also from languages of the local Epi-Jomon population, who were no longer hunter–gatherers but settled farmers by then. The relatively low internal diversity of the Tōhoku dialects may be attributed to the overall later spread of Japanese to the northeast compared with other areas of mainland Japan (Inoue, 1992). Migration of people from Izumo to the northeast may even have left a genetic trace. Saitō (2017, p. 127) uses a principal component analysis (PCA), in which nuclear DNA from modern Tōhoku individuals is compared with nuclear DNA from modern Ainu, Ryūkyūan and mainland Japanese individuals (Figure S4). A PCA simplifies complex datasets, creating summaries that emphasize the components explaining the maximum amount of variance. In population genetics, this method is often a quick and useful tool to examine population relationships, as the maximum amount of variance is often attributed to shared population history. However, it is not a formal test of shared ancestry. Saitō concludes that, in contrast to Ryūkyūans, the Tōhoku population has very low traces of Ainu-related ancestry, which was used as a proxy for Jōmon-related ancestry. He also includes a PCA showing the position of Izumo individuals relative to Okinawan and Kantō individuals (Saitō, 2017, p. 155), and he remarks upon the fact that these individuals occupy the same relative position as the Tōhoku individuals (Figure S4), namely they are to the lower right of the average Mainland Japanese individual. It is better to be cautious in drawing conclusions until more detailed comparisons from different areas of Japan are available, but the initial results are definitely interesting in light of the dialectal similarities between Izumo and the Tōhoku region. Concluding remarks Confronted with the Yayoi farmers and their new mode of subsistence, the different ethnic groups that were already present in Japan could react in different ways: assimilation and adoption of the new techniques, specialization in products with which to trade with the new farming populations, resistance or withdrawal. The available options differed per region and per period, influencing the way in which the Japanese language spread. The present-day dialect distribution in northern Honshū suggests that a considerable part of the early historic emishi population were speakers of an Izumo-type dialect. There certainly will have been Epi-Jomon people speaking an Ainu-related language among the emishi ranks, but what seems clear is that the Izumo-type dialect of Tōhoku must have already had a strong foothold in the northeast before the period of the Emishi Wars of the late eighth century. That dialect is proposed to have spread either with the introduction of rice agriculture by admixed Yayoi peoples in Mid to Late Yayoi, or in the expansion of the mounded tomb culture in the Kofun period. This study has highlighted a strong need to bring Japanese scholarship on the history and archaeology of Tōhoku into consideration with the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. The complexity of population movements in this area is illustrated by Hakomori (2013). Also needed is ancient DNA sequencing at fine temporal and geographic scales. With increasingly sophisticated techniques for quantifying genetic admixtures (cf. Chikhi, Nichols, Barbujani, & Beaumont, 2002; Dupanloup, Bertorelle, Chikhi, & Barbujani, 2004; Wollstein & Lao 2015), maybe Yayoi- to Nara-period skeletal material from the Kantō and Tōhoku regions will enlighten us on the interactions between indigenous peoples and migrants in the spread of agriculture to the northeast. The deep ancestry associated with the Jōmon will aid in highlighting changing proportions of different types of Asian-related ancestry in these different regions, although it behooves us to be alert to Jōmon continental interaction prior to the Yayoi period. Supplementary Material The supplementary material for this article can be found at doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2020.7. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Sept 18, 2021 22:14:57 GMT

An ancient DNA analysis reaching back thousands of years has provided a more detailed view of the ancestral groups contributing to present-day populations in Japan, uncovering genetic signals from three historical populations spanning pre- and post-agricultural periods.

"[O]ur study provides a detailed look into the changing genomic profile of the people who lived in the Japanese archipelago, both before and after agricultural and technologically driven population movements ended thousands of years of isolation from the rest of the continent," the study's authors, from research centers in Ireland and Japan, wrote.

For their analysis, published in Science Advances on Friday, the investigators sequenced the genomes of a dozen ancient samples from Japan, stretching back some 8,000 years, including representatives from pre-farming populations and populations present after agriculture was introduced.

When they analyzed the sequences in combination with five published genomes representing ancient individuals from an Indigenous Jomon hunter-gatherer-fisher population and a Yayoi farming population, they saw not only Jomon and Yayoi ancestry but also additional East Asian ancestry that arrived in the so-called Kofun period within the past 1,700 years.

The genetic features appeared to coincide with significant cultural changes in the region, the team pointed out. While pottery artifacts linked to the Jomon period have been detected as far back as 16,500 years ago, for example, wet rice paddy-based agriculture has been traced back some 3,000 years to the start of the Yayoi period. On the other hand, the Kofun period has been linked to an imperial state, with additional technological advances and a central political system.

"We now know that the ancestors derived from each of the foraging, agrarian, and state-formation phases made a significant contribution to the formation of Japanese populations today," co-senior author Shigeki Nakagome, a researcher at Trinity College Dublin, said in a statement. "In short, we have an entirely new tripartite model of Japanese genomic origins — instead of the dual-ancestry model that has been held for a significant time."

The investigators started by screening 14 ancient bone or tooth samples at six archeological sites in western and central regions of Japan, ultimately subjecting 12 samples to shotgun sequencing, including nine samples from the initial, early, middle, and late Jomon period and three Kofun period samples. The genomes were analyzed alongside published genomes for two Yayoi representatives dated at 2,000 years old and three individuals from late stages of the Jomon period.

The team's nuclear genome and mitochondrial haplogroup analyses highlighted the three ancestral groups contributing to the populations in Japan, while offering clues to the origins of groups migrating into the area. In particular, the Yayoi population that introduced wet rice agriculture showed genetic ties to Korea and other parts of northeast Asia, whereas the Kofun period was marked by new East Asian ancestry.

Based on admixture patterns, the authors found that agricultural populations in the Yayoi period carried both Jomon ancestry and ancestry from northeast Asia, whereas all three ancestry groups were represented in the genomes of the Kofun individuals and in today's Japanese.

"Our data provide evidence of a tri-ancestry structure for present-day Japanese populations, refining the established dual-structure model of admixed Jomon and Yayoi origins," the authors reported, adding that "ancestors characterizing each of the Jomon, Yayoi, and Kofun cultures made a significant contribution to the formation of Japanese populations today."

|

|