Post by Admin on Mar 4, 2024 2:15:43 GMT

A key aspect of the observed genome-wide patterns above is that these Jōmon individuals do not share any relationship with sampled ‘basal Asians’. In admixture tests (Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, Moorjani, Luo, Mallick, Rohland, Zhan and Reich2012), two populations that form a clade (e.g. the Jōmon and mainland present-day East Asians) may sometimes share excess ancestry with an outgroup population that potentially indicates partial shared demographic history, probably via a population closely related to the outgroup. However, Jōmon individuals show no excess connection to ‘basal Asians’, including the Southeast Asian Hòabìnhians relative to present-day East Asians, as indicated by the lack of significantly negative values in the Box (Figure 2A).

In particular, comparison of the Southeast Asian Hòabinhians from Laos and Malaysia with mainland East Asians from East Asia and a Jōmon individual (Ikawazu) shows that the East Asians and Jōmon ancestry are equidistant from Hòabìnhian ancestry (Figure 2A), indicating that the Jōmon do not share a special relationship with Hòabìnhians as previously suggested (McColl et al., Reference McColl, Racimo, Vinner, Demeter, Gakuhari, Moreno-Mayar and Willerslev2018). Tests of genetic similarity do not show Hòabìnhians or the Jōmon sharing exceptionally high genetic similarity with each other (Figure S1). Shared ancestry between present-day Japanese and recent Southeast Asians are best explained by a common process – gene flow from mainland East Asia, a phenomenon well-characterized by tests of the Dual Structure model in Japan and by observations of gene flow into Southeast Asia (Kanzawa-Kiriyama et al., Reference Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Kryukov, Jinam, Hosomichi, Saso, Suwa and Saitou2017, Reference Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Jinam, Kawai, Sato, Hosomichi, Tajima and Shinoda2019; Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Cheronet, Mallick, Rohland, Oxenham, Pietrusewsky and Reich2018). In the future, individuals from eastern Eurasia will almost certainly help to clarify how Jōmon ancestry first entered the Japanese archipelago, but the current sampling has not yet shed light on who they might have been.

Connections do exist between the Jōmon and East Asians who live along the coast of East Asia. The first Jōmon mtDNA sequenced in 1989, from the Early Jōmon Urawa-I site in the Kantō region (Figure 1), shared a close relationship to present-day Southeast Asians that suggests common ancestry with Southeast Asians (Horai et al., Reference Horai, Hayasaka, Murayama, Wate, Koike and Nakai1989). This haplogroup, called E1a1a, is prevalent in Austronesian-speaking populations of Taiwan and Southeast Asia who share a closer relationship to East Asians than other Southeast Asians. A ca. 8000-year-old individual sampled from Liang Island off the southeast coast of China in Fujian province also shares this haplogroup (Ko et al., Reference Ko, Chen, Fu, Delfin, Li, Chiu and Ko2014). Study of the Liang Island individual's nuclear genome indicates a close genetic relationship to Austronesians (Yang, MA and Fu, Q unpublished observations). Present-day Austronesians, such as the Ami and Atayal from Taiwan (Mallick et al., Reference Mallick, Li, Lipson, Mathieson, Gymrek, Racimo and Reich2016), share connections with the Ikawazu Jōmon relative to more inland ancient East Asians (Figure 2B and C), potentially indicating admixture between the Jōmon and southern East Asian populations. Comparisons with nuclear genomes from Fujian in southern China show similar connections (Yang, MA and Fu, Q unpublished observations). Thus, rather than Southeast Asian, the primary signal seems to be associated with Austronesians, who derive from an East Asian population associated with southern China.

Siberian connections, particularly in Hokkaido, have also been a recurring theme of Jōmon-related genetic studies. Several of the mtDNA haplogroups prevalent in the Japanese and Jōmon but rare in mainland East Asians, especially G1b, can be found in southeastern Siberians, highlighting potential contacts along the coast in northern East Asia as well (Sato et al., Reference Sato, Amano, Ono, Ishida, Kodera, Matsumara and Masuda2009; Adachi et al., Reference Adachi, Shinoda, Umetsu, Kitano, Matsumura, Fujiyama and Tanaka2011). Pre-modern Ainu show similar mtDNA haplogroups to populations in the Lower Amur region of Siberia and populations belonging to the early historic Okhotsk culture of Hokkaido (600–1200 AD) (Adachi, Kakuda, Takahashi, Kanzawa-Kiriyama, & Shinoda, Reference Adachi, Kakuda, Takahashi, Kanzawa-Kiriyama and Shinoda2018). Studies of nuclear DNA from Early Neolithic populations in the Primorye region of Russia highlight that the Jōmon are an outgroup to all mainland East Asians, including these more northern populations in Siberia (Sikora et al., Reference Sikora, Pitulko, Sousa, Allentoft, Vinner, Rasmussen and Willerslev2019; de Barros Damgaard et al., Reference de Barros Damgaard, Martiniano, Kamm, Moreno-Mayar, Kroonen, Peyrot and Willerslev2018). In the same comparisons set up for coastal southern East Asians above, it can be shown that ancient and present-day coastal northern mainland East Asians dating up to 7700 years ago share connections with the Ikawazu Jōmon relative to more inland East Asians (Figure 2B, C). Ancient northern Siberian ancestry prevalent during the Palaeolithic notable for both its closer relationship with European-related rather than Asian-related ancestry and its impact on Native American ancestry (Raghavan et al., Reference Raghavan, Skoglund, Graf, Metspalu, Albrechtsen, Moltke and Willerslev2014; Sikora et al., Reference Sikora, Pitulko, Sousa, Allentoft, Vinner, Rasmussen and Willerslev2019) is not found in mainland East Asians or the Jōmon, which emphasizes that the connections are specific to coastal mainland East Asians and the Jōmon.

One explanation for a connection between the Jōmon and coastal East Asians could be that the Jōmon were not completely isolated from mainland East Asians. By 3900 years ago, the date of the oldest Jōmon nuclear genome sampled (from Funadomari, Figure 1), Austronesians were rapidly expanding into islands in the Pacific (Tsang, Reference Tsang1992; Spriggs, Reference Spriggs2011). The main patterns observed both in past mtDNA studies and in recent genome-wide studies of the Jōmon all seem to highlight coastal connections, which may suggest that the Jōmon experienced gene flow with populations deriving from mainland East Asia prior to any contact associated with migration of Mumun immigrants from the Korean peninsula. This is supported by archaeological studies that track artefact commonalities resulting from trade and contact along the coast (Bausch, Reference Bausch and Hodos2017), some of which date back to the Palaeolithic (Morisaki, Reference Morisaki, Kaifu, Izuho, Goebel, Sato and Ono2015). This is logical given that the Jōmon were inveterate deep-sea fishers given their harpoon technology, and scores of dugout canoes have been excavated from archaeological sites (Habu, Reference Habu, Anderson, Barrett and Boyle2010) — although it is not clear how seaworthy they were.

To address the relationship between population movement and the spread of farming in the Japanese archipelago, Jōmon and Mumun ancestry must be well characterized. Here in this section, we have briefly highlighted some key features of Jōmon ancestry using ancient mtDNA and nuclear genomes. First, Jōmon ancestry diverged fairly early from that of mainland East Asians. Second, they do not show notable connections to currently sampled basal Asians, such as the Tianyuan individual or Hòabìnhians. Third, they share coastal connections with coastal populations in northern and southern East Asia. This suggests that one of the major assumptions about the Jōmon may not be true – that they were genetically isolated since the first Palaeolithic migrations to the Japanese archipelago until the Mumun migration at the end of the Jōmon period. If the Jōmon themselves are already partially admixed, then characterizing increased gene flow from the mainland in populations from the Yayoi or more recent historic periods will be substantially more complex.

Advances that utilize rare alleles or long haplotypes (Lawson & Falush, Reference Lawson and Falush2012; Schiffels et al., Reference Schiffels, Haak, Paajanen, Llamas, Popescu, Loe and Durbin2016) are increasing the power of demographic analyses focused on more closely related populations, including in Japan (Takeuchi et al., Reference Takeuchi, Katsuya, Kimura, Nabika, Isomura, Ohkubo and Kato2017), but these are still difficult to apply in the realm of ancient DNA where obtaining data with high enough coverage is still rare. Present-day genomes are informative on recent history (Takeuchi et al., Reference Takeuchi, Katsuya, Kimura, Nabika, Isomura, Ohkubo and Kato2017) but make it difficult to resolve questions about periods as early as the Yayoi. Ancient genomes directly from the Yayoi are needed to clarify early population movement associated with the spread of farming. Such sampling is just starting, where two nuclear genomes from the Shimo-Motoyama rock shelter site in northwest Kyushu dating to the Terminal Yayoi show evidence of admixture between Jōmon- and mainland East Asian-related ancestry, in a region where populations were thought to be of unadmixed Jōmon-lineage (Shinoda et al., Reference Shinoda, Kamisawa, Kakuda and Adachi2019). Characterizing the role admixture played during the Yayoi requires understanding of the features of Jōmon ancestry described above to help us understand how to contextualize these and future data.

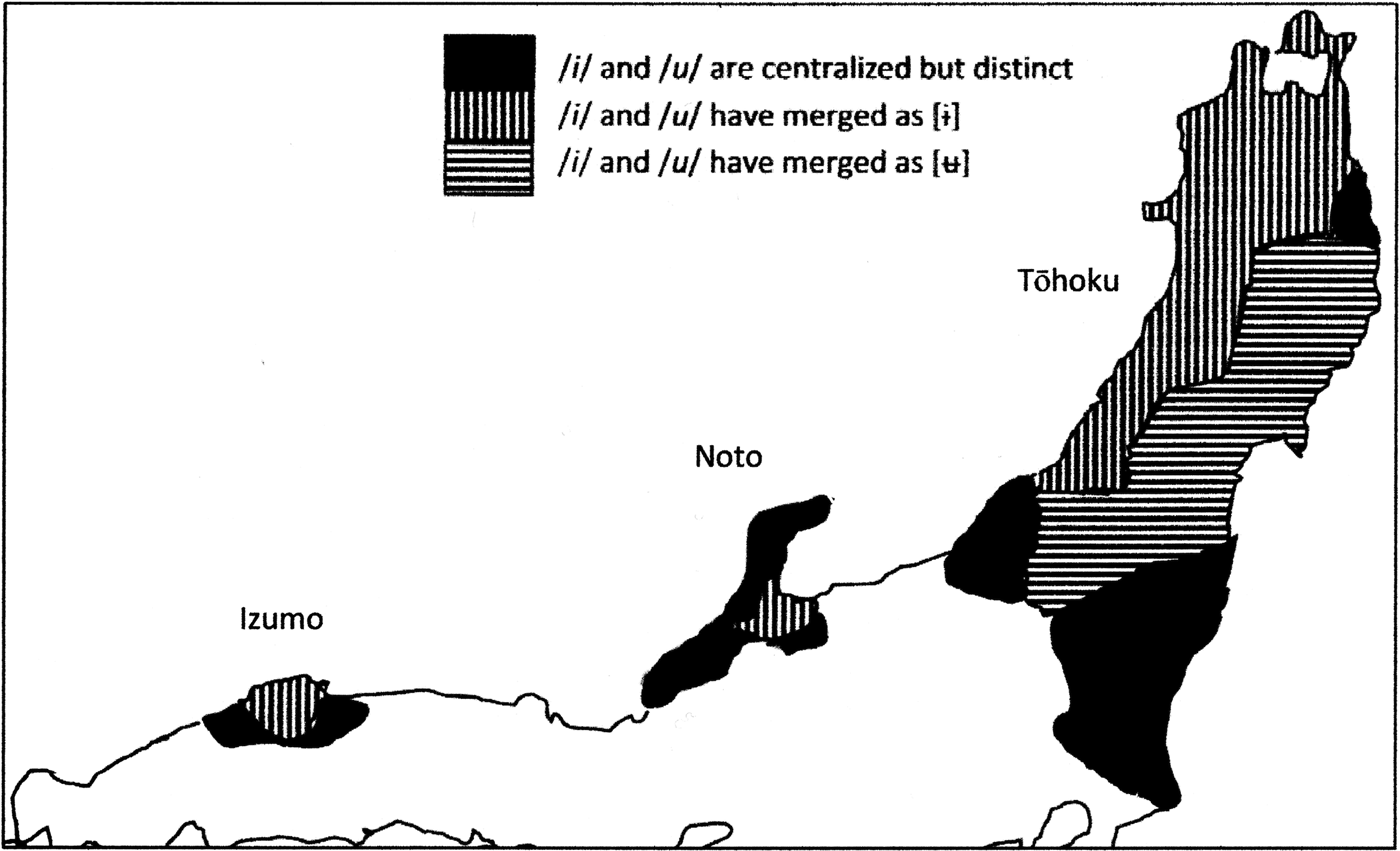

The remaining parts of this paper focus on populations in the Yayoi to Nara periods, examining (1) how archaeological shifts indicate a complex role for migration and admixture that was probably region-specific and (2) how similarities in dialect types hint at prehistoric migration of admixed Yayoi populations along the Japan Sea coast, which only stresses the need for more data on ancient Yayoi DNA.

The coastal genetic connections proposed are not directly tied to the farmer/language spread hypothesis because they are found in the Jōmon and thus would be prior to the spread of farming. Instead, they are a cautionary point – to understand farmer/language spread, we need to understand who were the pre-existing populations (the Jōmon). If their ancestry is not as genetically isolated as has been argued, then future studies need to account for that.

Agricultural transition in Japan

In dealing with this problem, first we must define ‘agriculture’. This is not as easy as it appears, since the Jōmon were experienced at plant management, leading to several local domesticated species. Thus, they can be called hunter–gatherer–fisher–horticulturalists. However, the plants that they domesticated or at least managed – soybeans, adzuki, Perilla, sweet chestnuts and Japanese millet (Echinochloa utilis) among others – were not suitable for intensive cultivation as carbohydrate sources to become staples (Crawford, Reference Crawford2011; Barnes, Reference Barnes2015: 111–112, and references therein). Crawford would rather discard the distinction between horticulture and agriculture, preferring to deal with proportionalities in ‘resource production’, which includes not only food but other strategic resources such as lacquer and hemp for fibres. Here, we use ‘agriculture’ to refer to the farming of major starch-grain crops: rice (Oryza sativa) and millets (Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum) in Early Yayoi, with barley and wheat added in later Yayoi.

The Jōmon subsistence system was interrupted by the importation of rice and millets from the Korean Peninsula in the Mumun Period, heralding the start of the Yayoi period in the Japanese Islands. The beginnings of rice agriculture in each region of Japan have been meticulously tracked, first from its source on the continent into North Kyushu (Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2017, Reference Miyamoto2018, Reference Miyamoto2019) and then eastwards through the archipelago (Fujio, Reference Fujio and Kenkyūkai2004, Reference Fujio2009, Reference Fujio2013, Reference Fujio2014, Reference Fujio2017). Proto-Japanese speaking Mumun migrants (Whitman, Reference Whitman2011) coming into North Kyushu interacted with Jōmon peoples there, creating an initial admixed Yayoi population which then spread throughout the Japanese islands as they occupied new lands for farming.

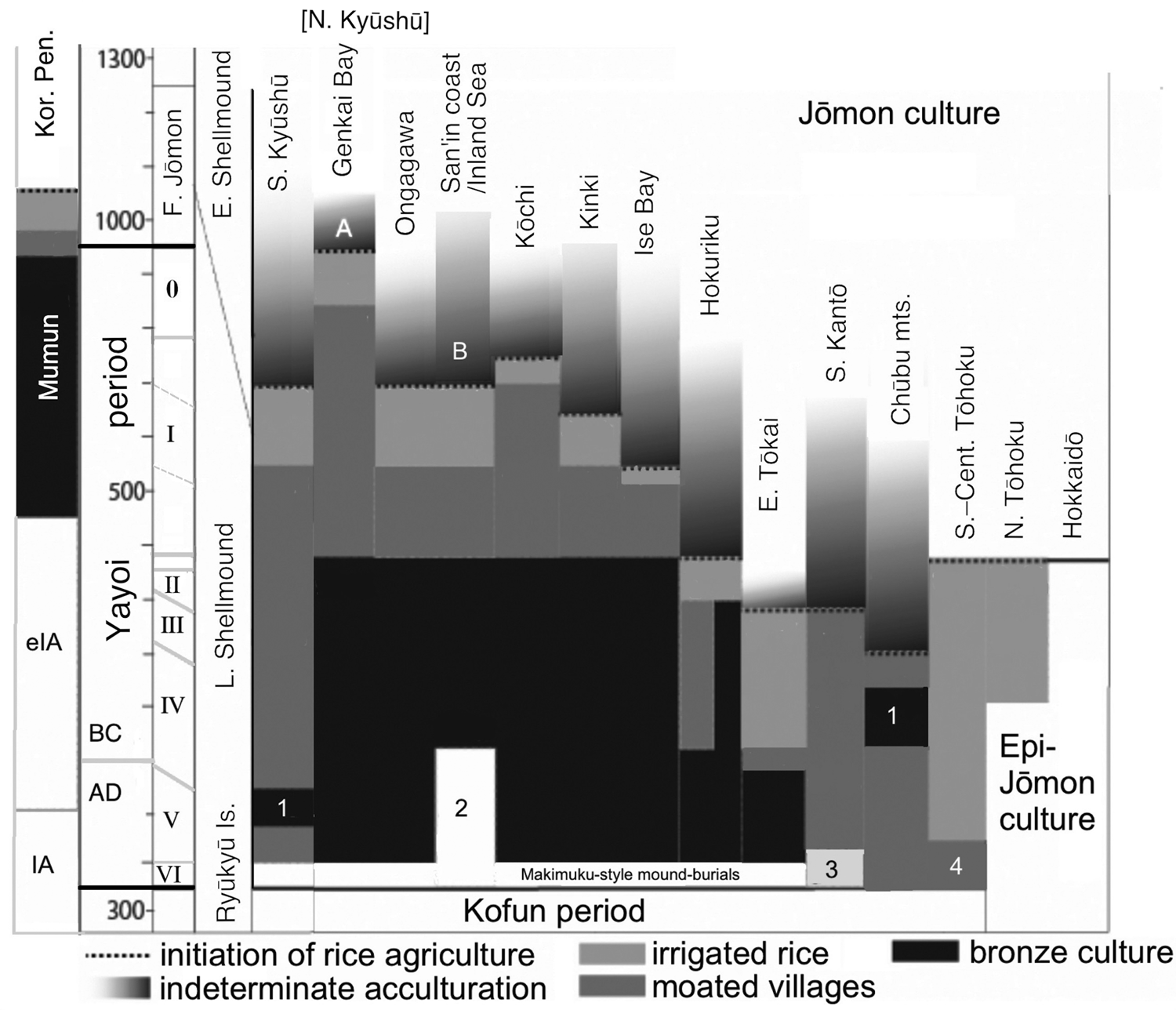

For each region, Fujio has identified a ‘hazy’ period of possible cultivation capped by the clear introduction of rice agriculture (Figure 3); he distinguishes this hazy period, however, from the clear adoption of irrigated rice agriculture and the appearance of the continental cultivation toolkit, moated settlements and moated burials. These elements have been treated as the ‘Yayoi package’ (Mizoguchi, Reference Mizoguchi2013) or ‘Yayoi complex’ (Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2016, Reference Miyamoto2019). Within most of western Honshu Island, Fujio expects that grain cultivation (rice and particularly millets) preceded the formal package. If we assume that the package was instituted by migrating farmers, the hazy periods and non-irrigated rice-farming periods could represent the gradual conversion of Jōmon-lineage peoples to an agricultural way of life. By 380 BC, however, the ‘Yayoi package’ entailing bronze and iron usage was fully established west of the ‘Waist of Honshu’ (between Wakasa Bay and Ise Bay, Figure 1).

In particular, comparison of the Southeast Asian Hòabinhians from Laos and Malaysia with mainland East Asians from East Asia and a Jōmon individual (Ikawazu) shows that the East Asians and Jōmon ancestry are equidistant from Hòabìnhian ancestry (Figure 2A), indicating that the Jōmon do not share a special relationship with Hòabìnhians as previously suggested (McColl et al., Reference McColl, Racimo, Vinner, Demeter, Gakuhari, Moreno-Mayar and Willerslev2018). Tests of genetic similarity do not show Hòabìnhians or the Jōmon sharing exceptionally high genetic similarity with each other (Figure S1). Shared ancestry between present-day Japanese and recent Southeast Asians are best explained by a common process – gene flow from mainland East Asia, a phenomenon well-characterized by tests of the Dual Structure model in Japan and by observations of gene flow into Southeast Asia (Kanzawa-Kiriyama et al., Reference Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Kryukov, Jinam, Hosomichi, Saso, Suwa and Saitou2017, Reference Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Jinam, Kawai, Sato, Hosomichi, Tajima and Shinoda2019; Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Cheronet, Mallick, Rohland, Oxenham, Pietrusewsky and Reich2018). In the future, individuals from eastern Eurasia will almost certainly help to clarify how Jōmon ancestry first entered the Japanese archipelago, but the current sampling has not yet shed light on who they might have been.

Connections do exist between the Jōmon and East Asians who live along the coast of East Asia. The first Jōmon mtDNA sequenced in 1989, from the Early Jōmon Urawa-I site in the Kantō region (Figure 1), shared a close relationship to present-day Southeast Asians that suggests common ancestry with Southeast Asians (Horai et al., Reference Horai, Hayasaka, Murayama, Wate, Koike and Nakai1989). This haplogroup, called E1a1a, is prevalent in Austronesian-speaking populations of Taiwan and Southeast Asia who share a closer relationship to East Asians than other Southeast Asians. A ca. 8000-year-old individual sampled from Liang Island off the southeast coast of China in Fujian province also shares this haplogroup (Ko et al., Reference Ko, Chen, Fu, Delfin, Li, Chiu and Ko2014). Study of the Liang Island individual's nuclear genome indicates a close genetic relationship to Austronesians (Yang, MA and Fu, Q unpublished observations). Present-day Austronesians, such as the Ami and Atayal from Taiwan (Mallick et al., Reference Mallick, Li, Lipson, Mathieson, Gymrek, Racimo and Reich2016), share connections with the Ikawazu Jōmon relative to more inland ancient East Asians (Figure 2B and C), potentially indicating admixture between the Jōmon and southern East Asian populations. Comparisons with nuclear genomes from Fujian in southern China show similar connections (Yang, MA and Fu, Q unpublished observations). Thus, rather than Southeast Asian, the primary signal seems to be associated with Austronesians, who derive from an East Asian population associated with southern China.

Siberian connections, particularly in Hokkaido, have also been a recurring theme of Jōmon-related genetic studies. Several of the mtDNA haplogroups prevalent in the Japanese and Jōmon but rare in mainland East Asians, especially G1b, can be found in southeastern Siberians, highlighting potential contacts along the coast in northern East Asia as well (Sato et al., Reference Sato, Amano, Ono, Ishida, Kodera, Matsumara and Masuda2009; Adachi et al., Reference Adachi, Shinoda, Umetsu, Kitano, Matsumura, Fujiyama and Tanaka2011). Pre-modern Ainu show similar mtDNA haplogroups to populations in the Lower Amur region of Siberia and populations belonging to the early historic Okhotsk culture of Hokkaido (600–1200 AD) (Adachi, Kakuda, Takahashi, Kanzawa-Kiriyama, & Shinoda, Reference Adachi, Kakuda, Takahashi, Kanzawa-Kiriyama and Shinoda2018). Studies of nuclear DNA from Early Neolithic populations in the Primorye region of Russia highlight that the Jōmon are an outgroup to all mainland East Asians, including these more northern populations in Siberia (Sikora et al., Reference Sikora, Pitulko, Sousa, Allentoft, Vinner, Rasmussen and Willerslev2019; de Barros Damgaard et al., Reference de Barros Damgaard, Martiniano, Kamm, Moreno-Mayar, Kroonen, Peyrot and Willerslev2018). In the same comparisons set up for coastal southern East Asians above, it can be shown that ancient and present-day coastal northern mainland East Asians dating up to 7700 years ago share connections with the Ikawazu Jōmon relative to more inland East Asians (Figure 2B, C). Ancient northern Siberian ancestry prevalent during the Palaeolithic notable for both its closer relationship with European-related rather than Asian-related ancestry and its impact on Native American ancestry (Raghavan et al., Reference Raghavan, Skoglund, Graf, Metspalu, Albrechtsen, Moltke and Willerslev2014; Sikora et al., Reference Sikora, Pitulko, Sousa, Allentoft, Vinner, Rasmussen and Willerslev2019) is not found in mainland East Asians or the Jōmon, which emphasizes that the connections are specific to coastal mainland East Asians and the Jōmon.

One explanation for a connection between the Jōmon and coastal East Asians could be that the Jōmon were not completely isolated from mainland East Asians. By 3900 years ago, the date of the oldest Jōmon nuclear genome sampled (from Funadomari, Figure 1), Austronesians were rapidly expanding into islands in the Pacific (Tsang, Reference Tsang1992; Spriggs, Reference Spriggs2011). The main patterns observed both in past mtDNA studies and in recent genome-wide studies of the Jōmon all seem to highlight coastal connections, which may suggest that the Jōmon experienced gene flow with populations deriving from mainland East Asia prior to any contact associated with migration of Mumun immigrants from the Korean peninsula. This is supported by archaeological studies that track artefact commonalities resulting from trade and contact along the coast (Bausch, Reference Bausch and Hodos2017), some of which date back to the Palaeolithic (Morisaki, Reference Morisaki, Kaifu, Izuho, Goebel, Sato and Ono2015). This is logical given that the Jōmon were inveterate deep-sea fishers given their harpoon technology, and scores of dugout canoes have been excavated from archaeological sites (Habu, Reference Habu, Anderson, Barrett and Boyle2010) — although it is not clear how seaworthy they were.

To address the relationship between population movement and the spread of farming in the Japanese archipelago, Jōmon and Mumun ancestry must be well characterized. Here in this section, we have briefly highlighted some key features of Jōmon ancestry using ancient mtDNA and nuclear genomes. First, Jōmon ancestry diverged fairly early from that of mainland East Asians. Second, they do not show notable connections to currently sampled basal Asians, such as the Tianyuan individual or Hòabìnhians. Third, they share coastal connections with coastal populations in northern and southern East Asia. This suggests that one of the major assumptions about the Jōmon may not be true – that they were genetically isolated since the first Palaeolithic migrations to the Japanese archipelago until the Mumun migration at the end of the Jōmon period. If the Jōmon themselves are already partially admixed, then characterizing increased gene flow from the mainland in populations from the Yayoi or more recent historic periods will be substantially more complex.

Advances that utilize rare alleles or long haplotypes (Lawson & Falush, Reference Lawson and Falush2012; Schiffels et al., Reference Schiffels, Haak, Paajanen, Llamas, Popescu, Loe and Durbin2016) are increasing the power of demographic analyses focused on more closely related populations, including in Japan (Takeuchi et al., Reference Takeuchi, Katsuya, Kimura, Nabika, Isomura, Ohkubo and Kato2017), but these are still difficult to apply in the realm of ancient DNA where obtaining data with high enough coverage is still rare. Present-day genomes are informative on recent history (Takeuchi et al., Reference Takeuchi, Katsuya, Kimura, Nabika, Isomura, Ohkubo and Kato2017) but make it difficult to resolve questions about periods as early as the Yayoi. Ancient genomes directly from the Yayoi are needed to clarify early population movement associated with the spread of farming. Such sampling is just starting, where two nuclear genomes from the Shimo-Motoyama rock shelter site in northwest Kyushu dating to the Terminal Yayoi show evidence of admixture between Jōmon- and mainland East Asian-related ancestry, in a region where populations were thought to be of unadmixed Jōmon-lineage (Shinoda et al., Reference Shinoda, Kamisawa, Kakuda and Adachi2019). Characterizing the role admixture played during the Yayoi requires understanding of the features of Jōmon ancestry described above to help us understand how to contextualize these and future data.

The remaining parts of this paper focus on populations in the Yayoi to Nara periods, examining (1) how archaeological shifts indicate a complex role for migration and admixture that was probably region-specific and (2) how similarities in dialect types hint at prehistoric migration of admixed Yayoi populations along the Japan Sea coast, which only stresses the need for more data on ancient Yayoi DNA.

The coastal genetic connections proposed are not directly tied to the farmer/language spread hypothesis because they are found in the Jōmon and thus would be prior to the spread of farming. Instead, they are a cautionary point – to understand farmer/language spread, we need to understand who were the pre-existing populations (the Jōmon). If their ancestry is not as genetically isolated as has been argued, then future studies need to account for that.

Agricultural transition in Japan

In dealing with this problem, first we must define ‘agriculture’. This is not as easy as it appears, since the Jōmon were experienced at plant management, leading to several local domesticated species. Thus, they can be called hunter–gatherer–fisher–horticulturalists. However, the plants that they domesticated or at least managed – soybeans, adzuki, Perilla, sweet chestnuts and Japanese millet (Echinochloa utilis) among others – were not suitable for intensive cultivation as carbohydrate sources to become staples (Crawford, Reference Crawford2011; Barnes, Reference Barnes2015: 111–112, and references therein). Crawford would rather discard the distinction between horticulture and agriculture, preferring to deal with proportionalities in ‘resource production’, which includes not only food but other strategic resources such as lacquer and hemp for fibres. Here, we use ‘agriculture’ to refer to the farming of major starch-grain crops: rice (Oryza sativa) and millets (Setaria italica and Panicum miliaceum) in Early Yayoi, with barley and wheat added in later Yayoi.

The Jōmon subsistence system was interrupted by the importation of rice and millets from the Korean Peninsula in the Mumun Period, heralding the start of the Yayoi period in the Japanese Islands. The beginnings of rice agriculture in each region of Japan have been meticulously tracked, first from its source on the continent into North Kyushu (Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2017, Reference Miyamoto2018, Reference Miyamoto2019) and then eastwards through the archipelago (Fujio, Reference Fujio and Kenkyūkai2004, Reference Fujio2009, Reference Fujio2013, Reference Fujio2014, Reference Fujio2017). Proto-Japanese speaking Mumun migrants (Whitman, Reference Whitman2011) coming into North Kyushu interacted with Jōmon peoples there, creating an initial admixed Yayoi population which then spread throughout the Japanese islands as they occupied new lands for farming.

For each region, Fujio has identified a ‘hazy’ period of possible cultivation capped by the clear introduction of rice agriculture (Figure 3); he distinguishes this hazy period, however, from the clear adoption of irrigated rice agriculture and the appearance of the continental cultivation toolkit, moated settlements and moated burials. These elements have been treated as the ‘Yayoi package’ (Mizoguchi, Reference Mizoguchi2013) or ‘Yayoi complex’ (Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2016, Reference Miyamoto2019). Within most of western Honshu Island, Fujio expects that grain cultivation (rice and particularly millets) preceded the formal package. If we assume that the package was instituted by migrating farmers, the hazy periods and non-irrigated rice-farming periods could represent the gradual conversion of Jōmon-lineage peoples to an agricultural way of life. By 380 BC, however, the ‘Yayoi package’ entailing bronze and iron usage was fully established west of the ‘Waist of Honshu’ (between Wakasa Bay and Ise Bay, Figure 1).