|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 28, 2021 20:44:29 GMT

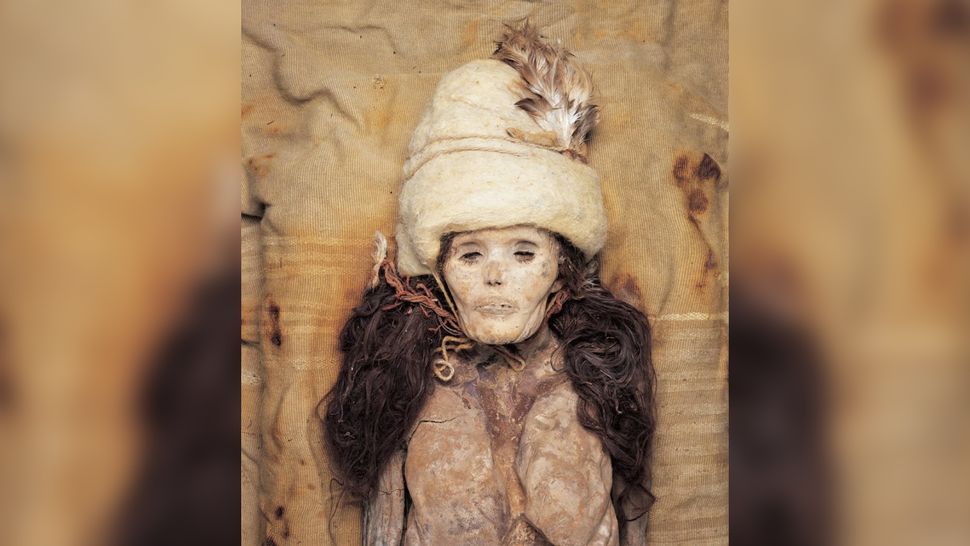

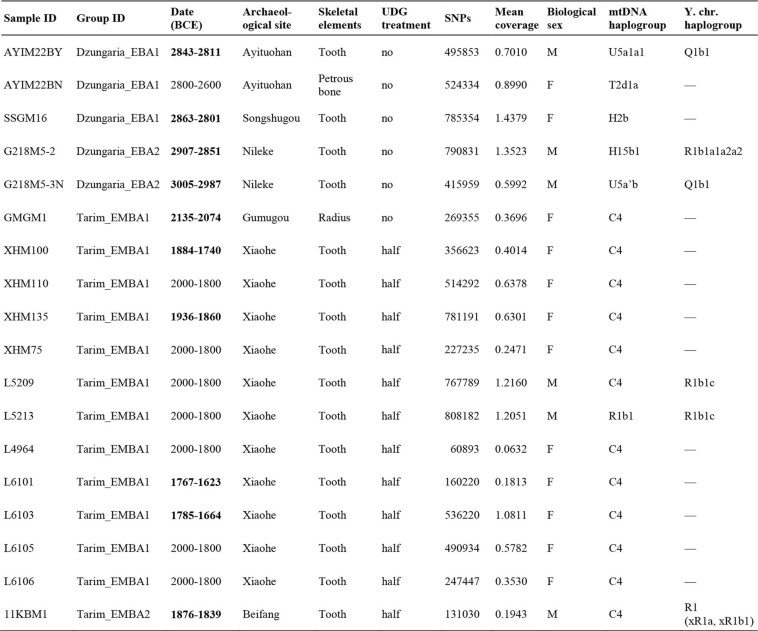

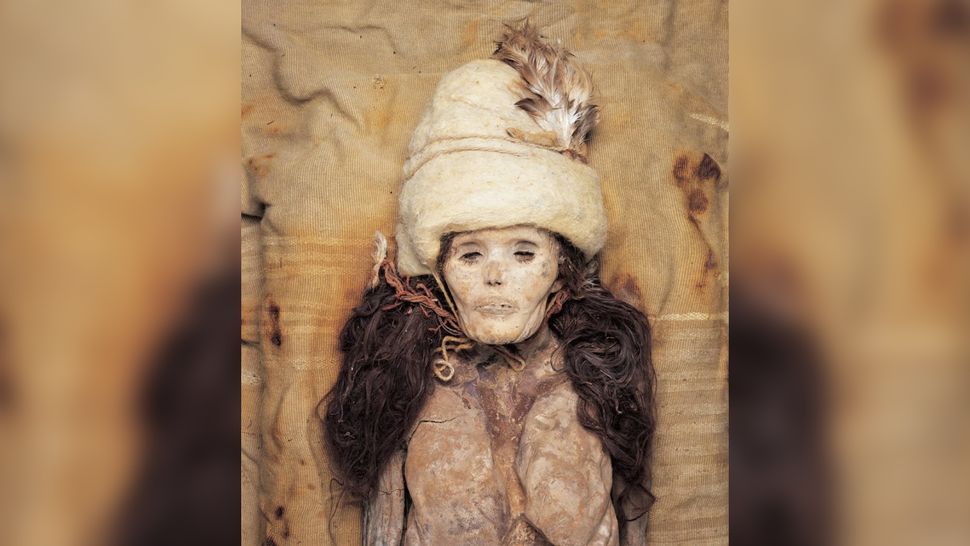

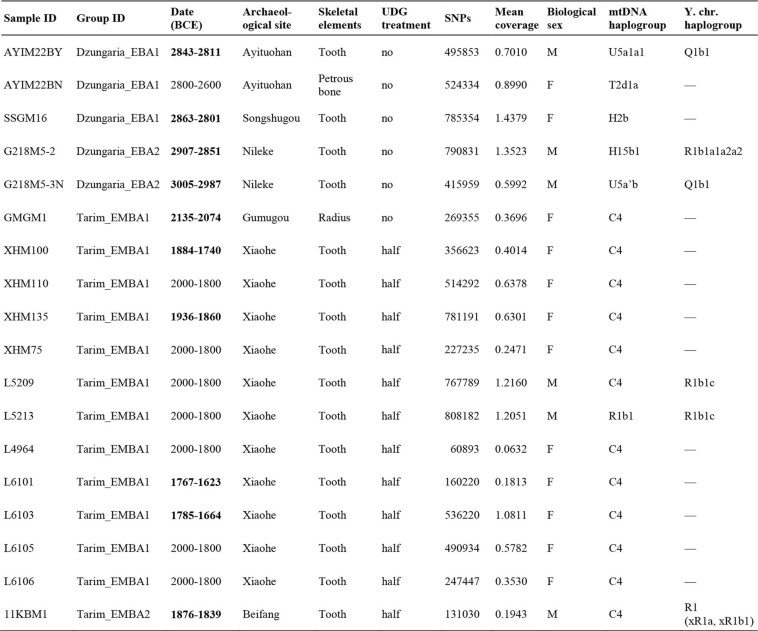

The mysterious Tarim mummies of China's western Xinjiang region are relics of a unique Bronze Age culture descended from Indigenous people, and not a remote branch of early Indo-Europeans, according to new genetic research. The new study upends more than a century of assumptions about the origins of the prehistoric people of the Tarim Basin whose naturally preserved human remains, desiccated by the desert, suggested to many archaeologists that they were descended from Indo-Europeans who had migrated to the region from somewhere farther west before about 2000 B.C. But the latest research shows that instead, they were a genetically isolated group seemingly unrelated to any neighboring peoples.  "They've been so enigmatic," said study co-author Christina Warinner, an anthropologist at Harvard University in Massachusetts and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany. "Ever since they were found almost by accident, they have raised so many questions, because so many aspects of them are either unique, puzzling or contradictory." The latest discoveries present almost as many new questions as they answer about the Tarim people, Warinner told Live Science. "It turns out, some of the leading ideas were incorrect, and so now we've got to start looking in a completely different direction," she said. The region around the Xiaohe cemetery is now a desert but it was a lush riverbank when the Tarim people lived there about 4000 years ago. The ancient burials at the Xiaohe cemetery were often marked with upright poles. This boat-shaped coffin was covered in a cattle hide and marked with an upright structure that seems to represent an oar.  Extended Data Table 1 A summary of the Bronze Age Xinjiang individuals reported in this study The Xiaohe cemetery was discovered by a local hunter in the early 20th century. More than 300 people were buried there in the Bronze Age but many of the tombs were looted by grave robbers before it was found. The new genetic study of the people buried at the Xiaohe cemetery indicates they were descended from indigenous people and not Indo-European migrants into the region, as was long theorized. One of the Tarim mummies buried at the Xiaohe cemetery. New research shows they were descended from indigenous people and not from Indo-European migrants to the region, as previously thought. Desert mummies European explorers found the first Tarim mummies in the deserts of what's now western China in the early 20th century. Recent research has focused on the mummies from the Xiaohe tomb complex on the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert. The naturally mummified remains, desiccated by the desert, were thought by some anthropologists to have non-Asian facial features, and some seemed to have red or fair hair. They were also dressed in clothes of wool, felt and leather that were unusual for the region. The Tarim culture was also distinctive. The people often buried their dead in boat-shaped wooden coffins and marked the burials with upright poles and grave markers shaped like oars. Some people were buried with pieces of cheese around their necks — possibly as food for an afterlife. These details suggested to some archaeologists that the Tarim people didn't originate in the region but rather were descendants of Indo-European people who had migrated there from somewhere else — perhaps southern Siberia or the mountains of Central Asia. Some scientists speculated that the Tarim people spoke an early form of Tocharian, an extinct Indo-European language spoken in the northern part of the region after A.D. 400. But the new study indicates that those assumptions were incorrect. DNA extracted from the teeth of 13 of the oldest mummies buried at Xiaohe about 4,000 years ago shows that there was no genetic mixing with neighboring people, said co-author Choongwon Jeong, a population geneticist at Seoul National University in South Korea. Instead, it now seems the Tarim people descended entirely from Ancient North Eurasians (ANE), a once-widespread Pleistocene population that had mostly disappeared about 10,000 years ago, after the end of the last ice age. ANE genetics now survive only fractionally in the genomes of some present-day populations, particularly among Indigenous people in Siberia and the Americas, the researchers wrote. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 28, 2021 22:09:17 GMT

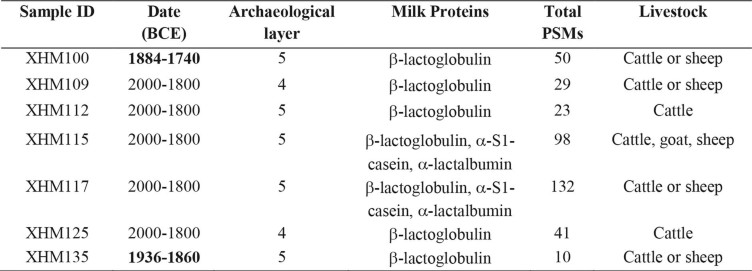

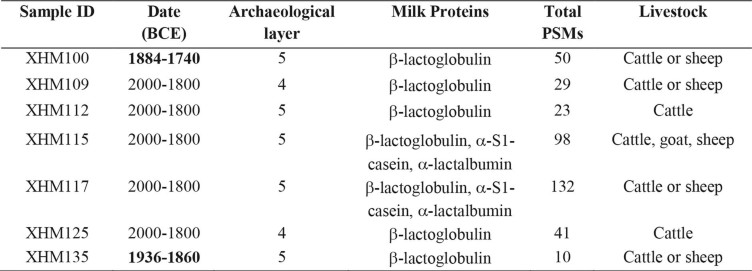

The study also compares the DNA of the Tarim mummies to that of desert mummies of about the same age discovered in the Dzungarian region in the north of Xinjiang, on the far side of the Tianshan mountain range that divides the region. It turned out that the ancient Dzungarian people, unlike the Tarim people roughly 500 miles (800 km) to the south, descended from both the Indigenous ANE and pastoralist herders from the Altai-Sayan mountains of southern Siberia called the Afanasievo, who had strong genetic links to the early Indo-European Yamnaya people of southern Russia, the researchers wrote. It was likely migrating Afanasievo herders had mixed with local hunter-gatherers in Dzungaria, while the Tarim people retained their original ANE ancestry, Jeong told Live Science in an email.  Extended Data Table 2 Dietary proteins identified in the dental calculus of individuals analyzed from the Tarim Basin Xiaohe cemetery However, it's not known why the Tarim people remained genetically isolated while the Dzungarians did not. "We speculate that the harsh environment of the Tarim Basin may have formed a barrier to gene flow, but we cannot be certain on this point at the moment," Jeong said. The desert environment doesn't seem to have cut the Tarim people off from cultural exchanges with many different peoples, however. The Tarim Basin in the Bronze Age was already a crossroads of cultural exchange between the East and the West and would remain so for thousands of years. "The Tarim people were genetically isolated from their neighbors while culturally extremely well connected," Jeong said.  Extended Data Table 3 Robustness of key qpAdm admixture models Among other things, they had adopted the foreign practices of herding cattle, goats and sheep, and of farming wheat, barley and millet, he said. "Probably such cultural elements were more productive in their local environment than hunting, gathering and fishing," Jeong said. "Our findings provide a strong case study showing that genes and cultural elements do not necessarily move together." Warinner said the ancient Tarim communities were sustained by ancient rivers that brought water to parts of the region while leaving the rest of it desert. "It was like a river oasis," she said. Parts of ancient fishing nets have been found at Tarim archaeological sites, and the practice of burying their dead in boat-shaped coffins with oars may have developed from their reliance on the rivers, she said. The rivers were fed by seasonal snow melt in the surrounding mountains, and often changed course when there had been an especially heavy snowfall over winter. When that happened, the ancient villages were effectively stranded far from water, and that may have contributed to the end of the Tarim Basin culture, she said. Today, the region is mostly desert. The study was published Oct. 27 in the journal Nature. Originally published on Live Science. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 29, 2021 19:28:06 GMT

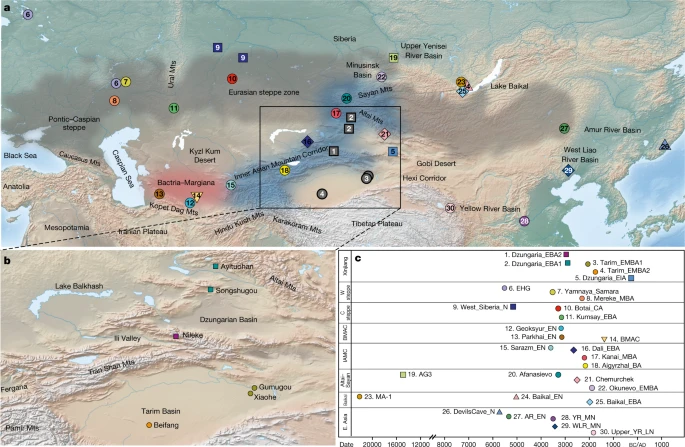

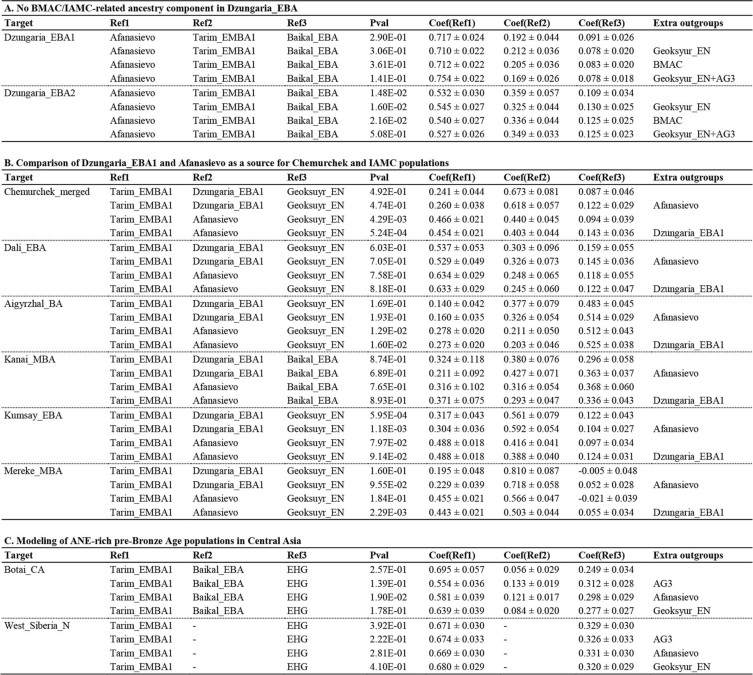

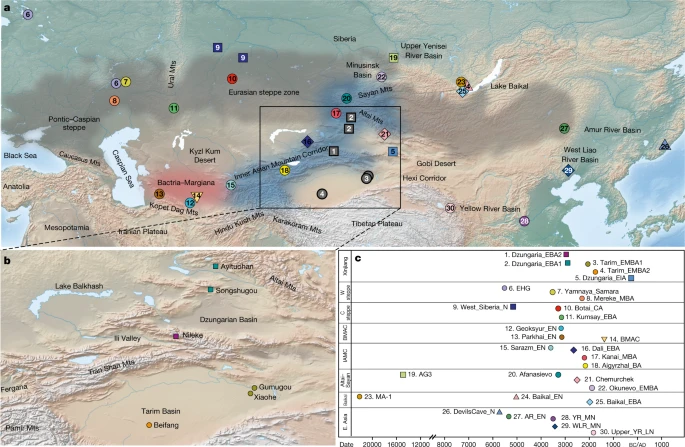

The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies Fan Zhang, Chao Ning, […]Yinqiu Cui Abstract The identity of the earliest inhabitants of Xinjiang, in the heart of Inner Asia, and the languages that they spoke have long been debated and remain contentious1. Here we present genomic data from 5 individuals dating to around 3000–2800 BC from the Dzungarian Basin and 13 individuals dating to around 2100–1700 BC from the Tarim Basin, representing the earliest yet discovered human remains from North and South Xinjiang, respectively. We find that the Early Bronze Age Dzungarian individuals exhibit a predominantly Afanasievo ancestry with an additional local contribution, and the Early–Middle Bronze Age Tarim individuals contain only a local ancestry. The Tarim individuals from the site of Xiaohe further exhibit strong evidence of milk proteins in their dental calculus, indicating a reliance on dairy pastoralism at the site since its founding. Our results do not support previous hypotheses for the origin of the Tarim mummies, who were argued to be Proto-Tocharian-speaking pastoralists descended from the Afanasievo1,2 or to have originated among the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex3 or Inner Asian Mountain Corridor cultures4. Instead, although Tocharian may have been plausibly introduced to the Dzungarian Basin by Afanasievo migrants during the Early Bronze Age, we find that the earliest Tarim Basin cultures appear to have arisen from a genetically isolated local population that adopted neighbouring pastoralist and agriculturalist practices, which allowed them to settle and thrive along the shifting riverine oases of the Taklamakan Desert. Main As part of the Silk Road and located at the geographic confluence of Eastern and Western cultures, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (henceforth Xinjiang) has long served as a major crossroads for trans-Eurasian exchanges of people, cultures, agriculture and languages1,5,6,7,8,9. Bisected by the Tianshan mountains, Xinjiang can be divided into two subregions referred to as North Xinjiang, which contains the Dzungarian Basin, and South Xinjiang, which contains the Tarim Basin (Fig. 1). The Dzungarian Basin in the north consists of the Gurbantünggüt Desert, which is surrounded by a vast expanse of grasslands traditionally inhabited by mobile pastoralists. The southern part of Xinjiang consists of the Tarim Basin, a dry inland sea that now forms the Taklamakan Desert. Although mostly uninhabitable, the Tarim Basin also contains small oases and riverine corridors, fed by runoff from thawing glacier ice and snow from the surrounding high mountains4,10,11. Fig. 1: Overview of the Xinjiang Bronze Age archaeological sites analysed in this study.  a, Overview of key Eurasian geographic regions, features and archaeological sites discussed in the text; new sites analysed in this study are shown in grey. b, Enhanced view of Xinjiang and the six new sites analysed in this study. c, Timeline of the sites in a. The timeline is organized by region, and the median date for each studied group is shown. The base maps in a and b were obtained from the Natural Earth public domain map dataset (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-raster-data/10m-cross-blend-hypso/). In the group labels, the suffixes represent the archaeological time periods of each group: N, Neolithic; EN, MN and LN, Early, Middle and Late Neolithic, respectively; EN, Eneolithic for Geoksyur, Parkhai and Sarazm; CA, Chalcolithic Age; BA, Bronze Age; MBA, Middle Bronze Age; EIA, Early Iron Age. MA-1, Mal'ta; EHG, Eastern European hunter-gatherers. Within and around the Dzungarian Basin, pastoralist Early Bronze Age (EBA) Afanasievo (3000–2600 BC) and Chemurchek (or Qiemu’erqieke) (2500–1700 BC)12 sites have been plausibly linked to the Afanasievo herders of the Altai–Sayan region in southern Siberia (3150–2750 BC), who in turn have close genetic ties with the Yamnaya (3500–2500 BC) of the Pontic–Caspian steppe located 3,000 km to the west13,14,15. Linguists have hypothesized that the Afanasievo dispersal brought the now extinct Tocharian branch of the Indo-European language family eastwards, separating it from other Indo-European languages by the third or fourth millennium BC (ref. 14). However, although Afanasievo-related ancestry has been confirmed among Iron Age Dzungarian populations (around 200–400 BC)7, and Tocharian is recorded in Buddhist texts from the Tarim Basin dating to AD 500–1000 (ref. 13), little is known about earlier Xinjiang populations and their possible genetic relationships with the Afanasievo or other groups. Since the late 1990s, the discovery of hundreds of naturally mummified human remains dating to around 2000 BC to AD 200 in the Tarim Basin has attracted international attention due to their so-called Western physical appearance, their felted and woven woollen clothing, and their agropastoral economy that included cattle, sheep/goats, wheat, barley, millet and even kefir cheese16,17,18,19. Such mummies have now been found throughout the Tarim Basin, among which the earliest are those found in the lowest layers of the cemeteries at Gumugou (2135–1939 BC), Xiaohe (1884–1736 BC) and Beifang (1785–1664 BC) (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 1). These and related Bronze Age sites are grouped within the Xiaohe archaeological horizon on the basis of their shared material culture13,16,20. Multiple contrasting hypotheses have been suggested by scholars to explain the origins and Western elements of the Xiaohe horizon, including the Yamnaya/Afanasievo steppe hypothesis16, the Bactrian oasis hypothesis21 and the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor (IAMC) island biogeography hypothesis4. The Yamnaya/Afanasievo steppe hypothesis posits that the Afanasievo-related EBA populations in the Altai–Sayan mountains spread via the Dzungarian Basin into the Tarim Basin and subsequently founded the agropastoralist communities making up the Xiaohe horizon around 2000 BC (refs. 16,22,23). By contrast, the Bactrian oasis hypothesis posits that the Tarim Basin was initially colonized by migrating farmers of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) (around 2300–1800 BC) from the desert oases of Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan via the mountains of Central Asia. Support for this hypothesis is largely based on similarities in the agricultural and irrigation systems between the two regions that reflect adaptations to a desert environment, as well as evidence for the ritual use of Ephedra at both locations3,21. The IAMC island biogeography hypothesis similarly posits a mountain Central Asian origin for the Xiaohe founder population, but one linked to the transhumance of agropastoralists in the IAMC to the west and north of the Tarim Basin4,24,25. In contrast to these three migration models, the greater IAMC, which spans the Hindu Kush to Altai mountains, may have alternatively functioned as a geographic arena through which cultural ideas, rather than populations, primarily moved25. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 30, 2021 4:20:44 GMT

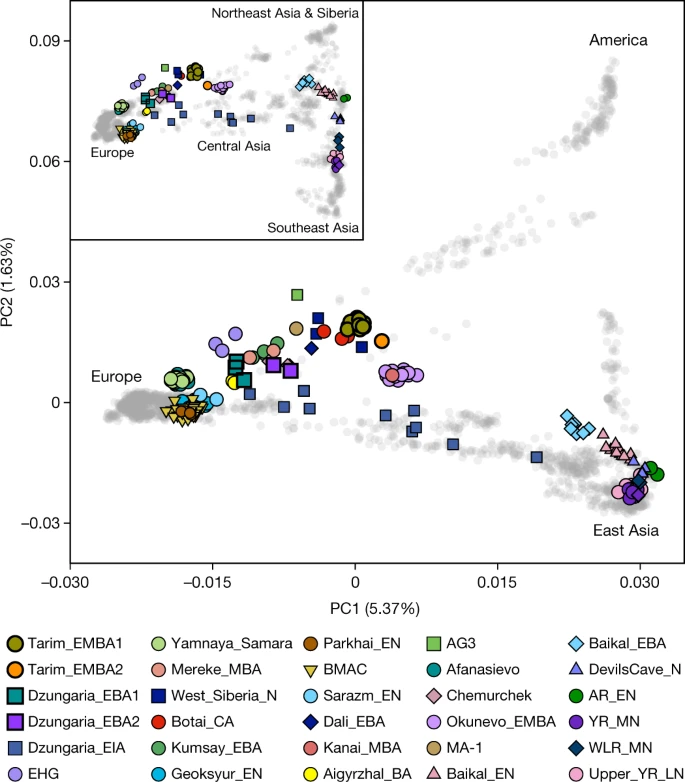

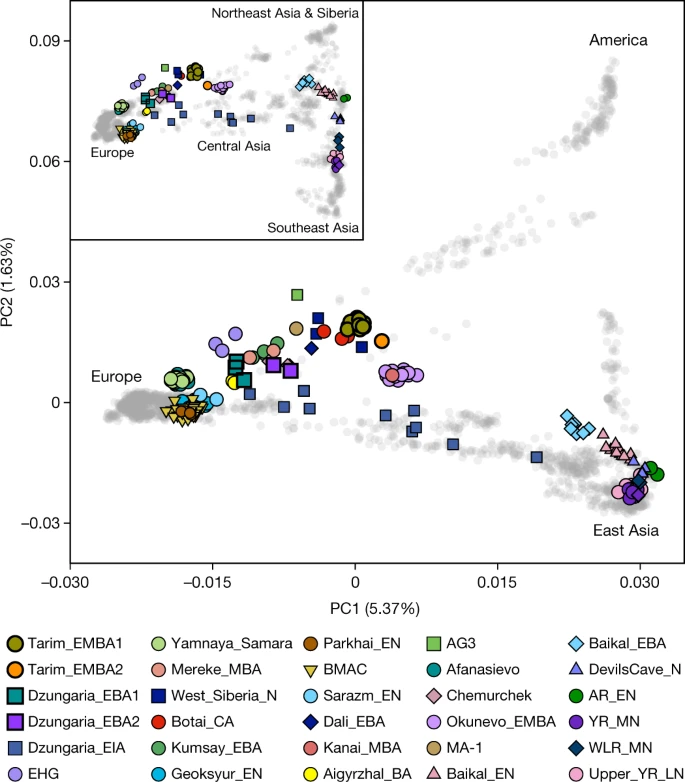

Recent archaeogenomic research has shown that Bronze Age Afanasievo of southern Siberia and IAMC/BMAC populations of Central Asia have distinguishable genetic profiles15,26, and that these profiles are likewise also distinct from those of pre-agropastoralist hunter-gatherer populations in Inner Asia2,5,7,27,28,29,30. As such, an archaeogenomic investigation of Bronze Age Xinjiang populations presents a powerful approach for reconstructing the population histories of the Dzungarian and Tarim basins and the origins of the Bronze Age Xiaohe horizon. Examining the skeletal material of 33 Bronze Age individuals from sites in the Dzungarian (Nileke, Ayituohan and Songshugou) and Tarim (Xiaohe, Gumugou and Beifang) basins, we successfully retrieved ancient genome sequences from 5 EBA Dzungarian individuals (3000–2800 BC) culturally assigned as Afanasievo, and genome-wide data from 13 Early–Middle Bronze Age (EMBA) Tarim individuals (2100–1700 BC) belonging to the Xiaohe horizon (Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1A). We additionally report dental calculus proteomes of seven individuals from basal layers at the site of Xiaohe in the Tarim Basin (Extended Data Table 2). To the best of our knowledge, these individuals represent the earliest human remains excavated to date in the region. Genetic diversity of the Bronze Age Xinjiang We obtained genome-wide data for 18 of 33 attempted individuals by either whole-genome sequencing or DNA enrichment for a panel of about 1.2 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (1,240k panel SNPs) (Supplementary Data 1A). Overall, endogenous DNA was well preserved with minimal levels of contamination (Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1A). To explore the genetic profiles of ancient Xinjiang populations, we first calculated the principal components of present-day Eurasian and Native American populations onto which we projected those of ancient individuals. Ancient Xinjiang individuals form several distinct clusters distributed along principal component 1 (PC1) (Fig. 2), the main principal component that separates eastern and western Eurasian populations. EBA Dzungarian individuals from the sites of Ayituohan and Songshugou near the Altai Mountains (Dzungaria_EBA1) fall close to EBA Afanasievo steppe herders from the Altai–Sayan mountains to the north. Genetic clustering with ADMIXTURE further supports this observation (Extended Data Fig. 3). The contemporaneous individuals from the Nileke site near the Tianshan mountains (Dzungaria_EBA2) are slightly shifted along PC1 towards the later Tarim individuals. In contrast to the EBA Dzungarian individuals, the EMBA individuals from the eastern Tarim sites of Xiaohe and Gumugou (Tarim_EMBA1) form a tight cluster close to pre-Bronze Age central steppe and Siberian individuals who share a high level of ancient North Eurasian (ANE) ancestry (for example, Botai_CA). A contemporaneous individual from the Beifang site (Tarim_EMBA2) in the southern Tarim Basin is slightly displaced from the Tarim_EMBA1 towards EBA individuals from the Baikal region. Fig. 2: Genetic structure of ancient and present-day populations included in this study.  Principal component analysis of ancient individuals projected onto Eurasian and Native American populations; the inset displays ancient individuals projected onto only Eurasian populations. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Oct 30, 2021 20:06:01 GMT

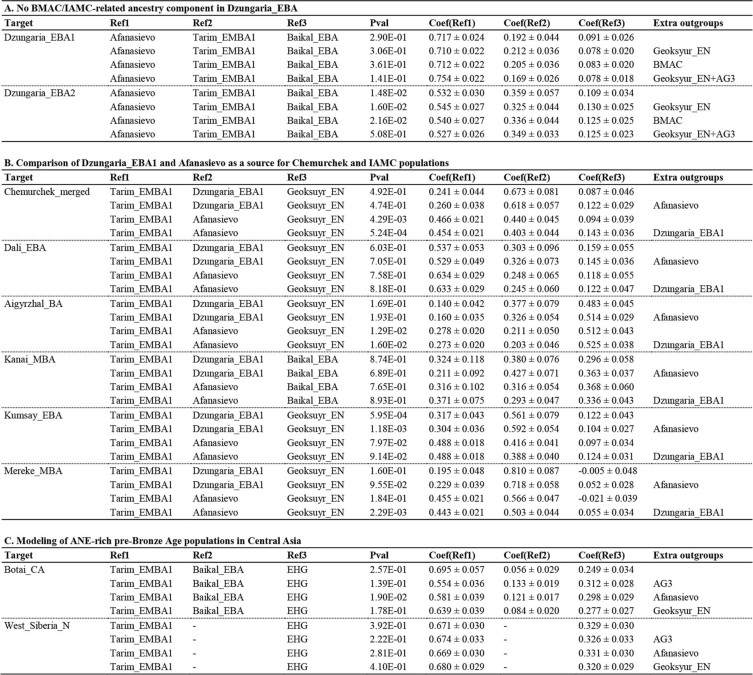

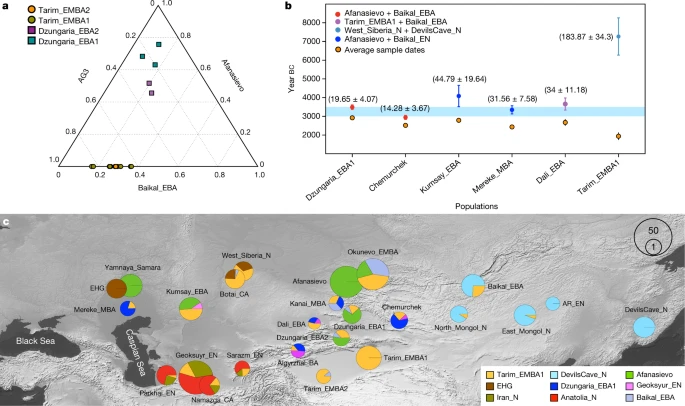

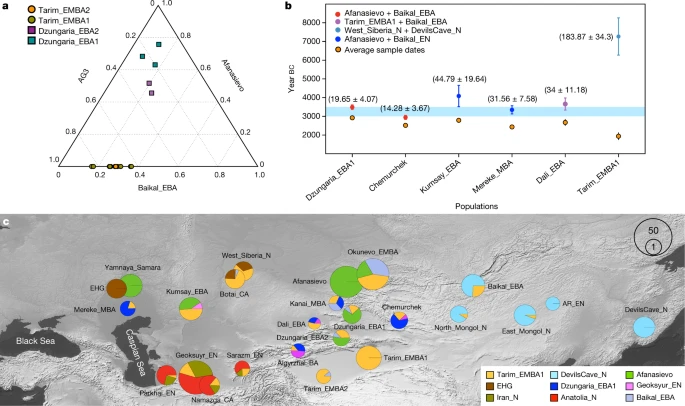

Afanasievo genetic legacy in Dzungaria Outgroup f3 statistics supports a tight genetic link between the Dzungarian and Tarim groups (Extended Data Fig. 2A). Nevertheless, both of the Dzungarian groups are significantly different from the Tarim groups, showing excess affinity with various western Eurasian populations and sharing fewer alleles with ANE-related groups (Extended Data Fig. 2b, c). To understand this mixed genetic profile, we used qpAdm to explore admixture models of the Dzungarian groups with Tarim_EMBA1 or a terminal Pleistocene individual (AG3) from the Siberian site of Afontova Gora31, as a source (Supplementary Data 1D). AG3 is a distal representative of the ANE ancestry and shows a high affinity with Tarim_EMBA1. Although the Tarim_EMBA1 individuals lived a millennium later than the Dzungarian groups, they are more genetically distant from the Afanasievo than the Dzungarian groups, suggesting that they have a higher proportion of local autochthonous ancestry. Here we define autochthonous to signify a genetic profile that has been present in a region for millennia, rather than being associated with more recently arrived groups. We find that Dzungaria_EBA1 and Dzungaria_EBA2 are both best described by three-way admixture models (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Table 3 and Supplementary Data 1D) in which they derive a majority ancestry from Afanasievo (about 70% in Dzungaria_EBA1 and about 50% in Dzungaria_EBA2), with the remaining ancestry best modelled as a mixture of AG3/Tarim_EMBA1 (19–36%) and Baikal_EBA (9–21%). When we use Eneolithic and Bronze Age populations from the IAMC as a source, models fail when Afanasievo is not included as a source, and no contribution is allocated to the IAMC groups when Afanasievo is included (Supplementary Data 1D). Thus, Afanasievo ancestry, without IAMC contributions, is sufficient to explain the western Eurasian component of the Dzungarian individuals. We also find that the Chemurchek, an EBA pastoralist culture that succeeds the Afanasievo in both the Dzungarian Basin and Altai Mountains, derive approximately two-thirds of their ancestry from Dzungaria_EBA1 with the remainder from Tarim_EMBA1 and IAMC/BMAC-related sources (Fig. 3, Extended Data Table 3, Supplementary Data 1F and Supplementary Text 5). This helps to explain both the IAMC/BMAC-related ancestry previously noted in Chemurchek individuals30 and their reported cultural and genetic affiliations to Afanasievo groups32. Taken together, these results indicate that the early dispersal of the Afanasievo herders into Dzungaria was accompanied by a substantial level of genetic mixing with local autochthonous populations, a pattern distinct from that of the initial formation of the Afanasievo culture in southern Siberia. Fig. 3: Genetic ancestry and admixture dating of ancient populations from Xinjiang and its vicinity.  a, qpAdm-based estimates of the ancestry proportion of Dzungaria_EBA and Tarim_EMBA from three ancestry sources (AG3, Afanasievo and Baikal_EBA) (Supplementary Data 1D, E). Unlike Dzungaria_EBA individuals, Tarim_EMBA individuals are adequately modelled without EBA Eurasian steppe pastoralist (for example, Afanasievo) ancestry. b, Genetic admixture dates for key Bronze Age populations in Inner Asia, including Dzungaria_EBA1 (n = 3), Chemurchek (n = 3), Kumsay_EBA (n = 4), Mereke_MBA (n = 2), Dali_EBA (n = 1) and Tarim_EMBA1 (n = 12). The blue shade represents the radiocarbon dating range of the Yamnaya and Afanasievo individuals. The orange circles and the associated vertical bars represent the averages and standard deviations of median radiocarbon dates, respectively. The circles above each orange circle represent the estimated admixture dates with a generation time of 29 years, and the vertical bars represent the sum of standard errors of the admixture date and the radiocarbon date estimate. c, Representative qpAdm-based admixture models of ancient Eurasian groups (Supplementary Data 1D–I). For Dzungaria_EBA1 and Geoksyur_EN, we show their three-way admixture models including Tarim_EMBA1 as a source. For later populations in Xinjiang, IAMC and nearby regions, we used them as sources, and allocated a colour to each of them (blue for Dzungaria_EBA1; magenta for Geoksyur_EN). The base map in c was obtained from the Natural Earth public domain map dataset (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-raster-data/10m-gray-earth/). Genetic isolation of the Tarim group The Tarim_EMBA1 and Tarim_EMBA2 groups, although geographically separated by over 600 km of desert, form a homogeneous population that had undergone a substantial population bottleneck, as suggested by their high genetic affinity without close kinship, as well as by the limited diversity in their uniparental haplogroups (Figs. 1 and 2, Extended Data Fig. 4, Extended Data Table 1, Supplementary Data 1B and Supplementary Text 4). Using qpAdm, we modelled the Tarim Basin individuals as a mixture of two ancient autochthonous Asian genetic groups: the ANE, represented by an Upper Palaeolithic individual from the Afontova Gora site in the upper Yenisei River region of Siberia (AG3) (about 72%), and ancient Northeast Asians, represented by Baikal_EBA (about 28%) (Supplementary Data 1E and Fig. 3a). Tarim_EMBA2 from Beifang can also be modelled as a mixture of Tarim_EMBA1 (about 89%) and Baikal_EBA (about 11%). For both Tarim groups, admixture models unanimously fail when using the Afanasievo or IAMC/BMAC groups as a western Eurasian source (Supplementary Data 1E), thus rejecting a western Eurasian genetic contribution from nearby groups with herding and/or farming economies. We estimate a deep formation date for the Tarim_EMBA1 genetic profile, consistent with an absence of western Eurasian EBA admixture, placing the origin of this gene pool at 183 generations before the sampled Tarim Basin individuals, or 9,157 ± 986 years ago when assuming an average generation time of 29 years (Fig. 3b). Considering these findings together, the genetic profile of the Tarim Basin individuals indicates that the earliest individuals of the Xiaohe horizon belong to an ancient and isolated autochthonous Asian gene pool. This autochthonous ANE-related gene pool is likely to have formed the genetic substratum of the pre-pastoralist ANE-related populations of Central Asia and southern Siberia (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Text 5). |

|