Post by Admin on Oct 31, 2021 4:04:27 GMT

Pastoralism in the Tarim Basin

Although the harsh environment of the Tarim Basin may have served as a strong barrier to gene flow into the region, it was not a barrier to the flow of ideas or technologies, as foreign innovations, such as dairy pastoralism and wheat and millet agriculture, came to form the basis of the Bronze Age Tarim economies. Woollen fabrics, horns and bones of cattle, sheep and goats, livestock manure, and milk and kefir-like dairy products have been recovered from the upper layers of the Xiaohe and Gumugou cemeteries33,34,35,36, as have wheat and millet seeds and bundles of Ephedra twigs34,37,38. Famously, many of the mummies dating to 1650–1450 BC were even buried with lumps of cheese35. However, until now it has not been clear whether this pastoralist lifestyle also characterized the earliest layers at Xiaohe.

To better understand the dietary economy of the earliest archaeological periods, we analysed the dental calculus proteomes of seven individuals at the site of Xiaohe dating to around 2000–1700 BC. All seven individuals were strongly positive for ruminant-milk-specific proteins (Extended Data Table 2), including β-lactoglobulin, α-S1-casein and α-lactalbumin (Extended Data Fig. 5), and peptide recovery was sufficient to provide taxonomically diagnostic matches to cattle (Bos), sheep (Ovis) and goat (Capra) milk (Extended Data Fig. 5, Extended Data Table 2 and Supplementary Data 3). These results confirm that dairy products were consumed by individuals of autochthonous ancestry (Tarim_EMBA1) buried in the lowest levels of the Xiaohe cemetery (Extended Data Table 2). Importantly, however, and in contrast to previous hypotheses36, none of the Tarim individuals was genetically lactase persistent (Supplementary Data 1J). Rather, the Tarim mummies contribute to a growing body of evidence that prehistoric dairy pastoralism in Inner and East Asia spread independently of lactase persistence genotypes28,30.

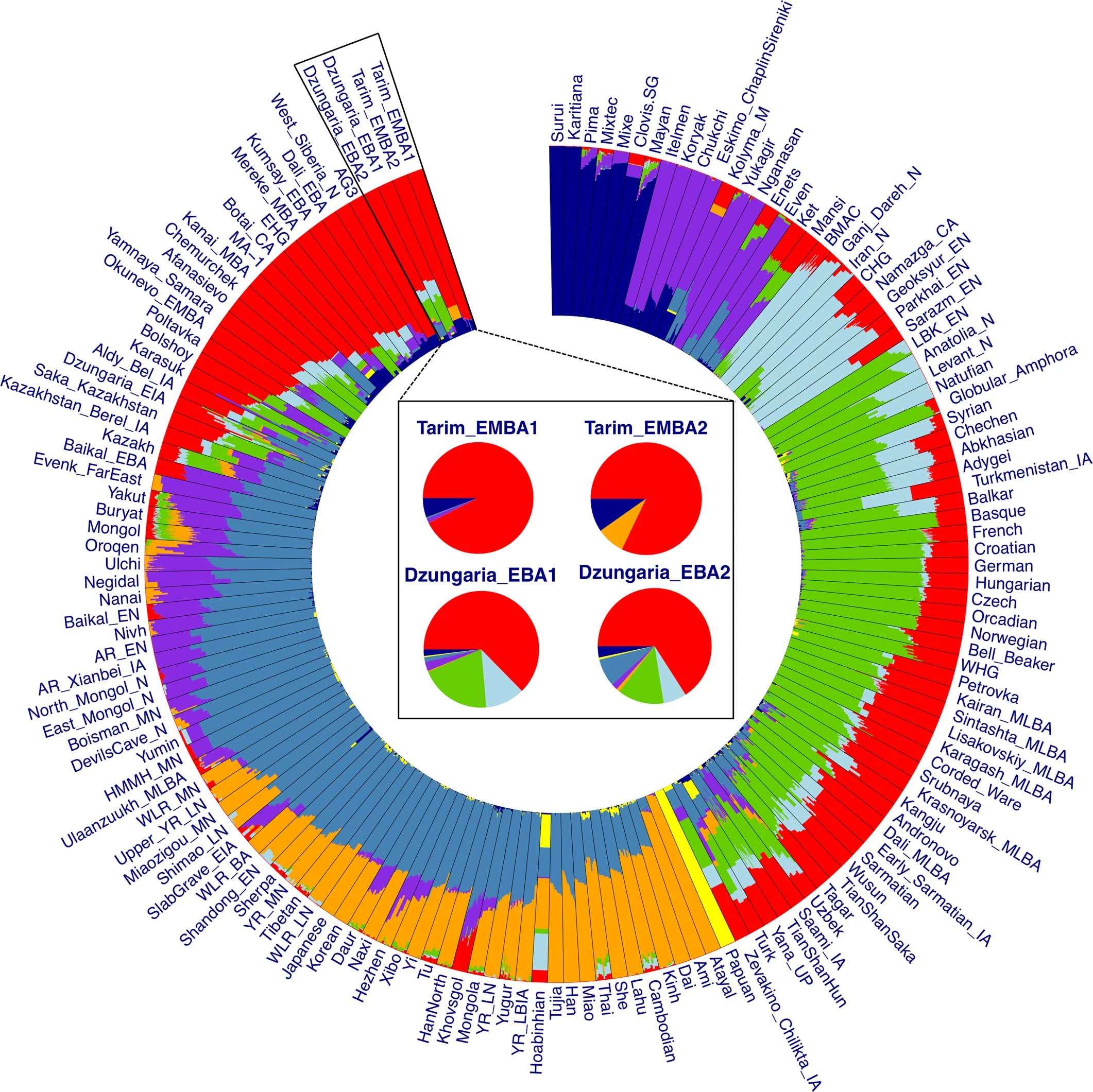

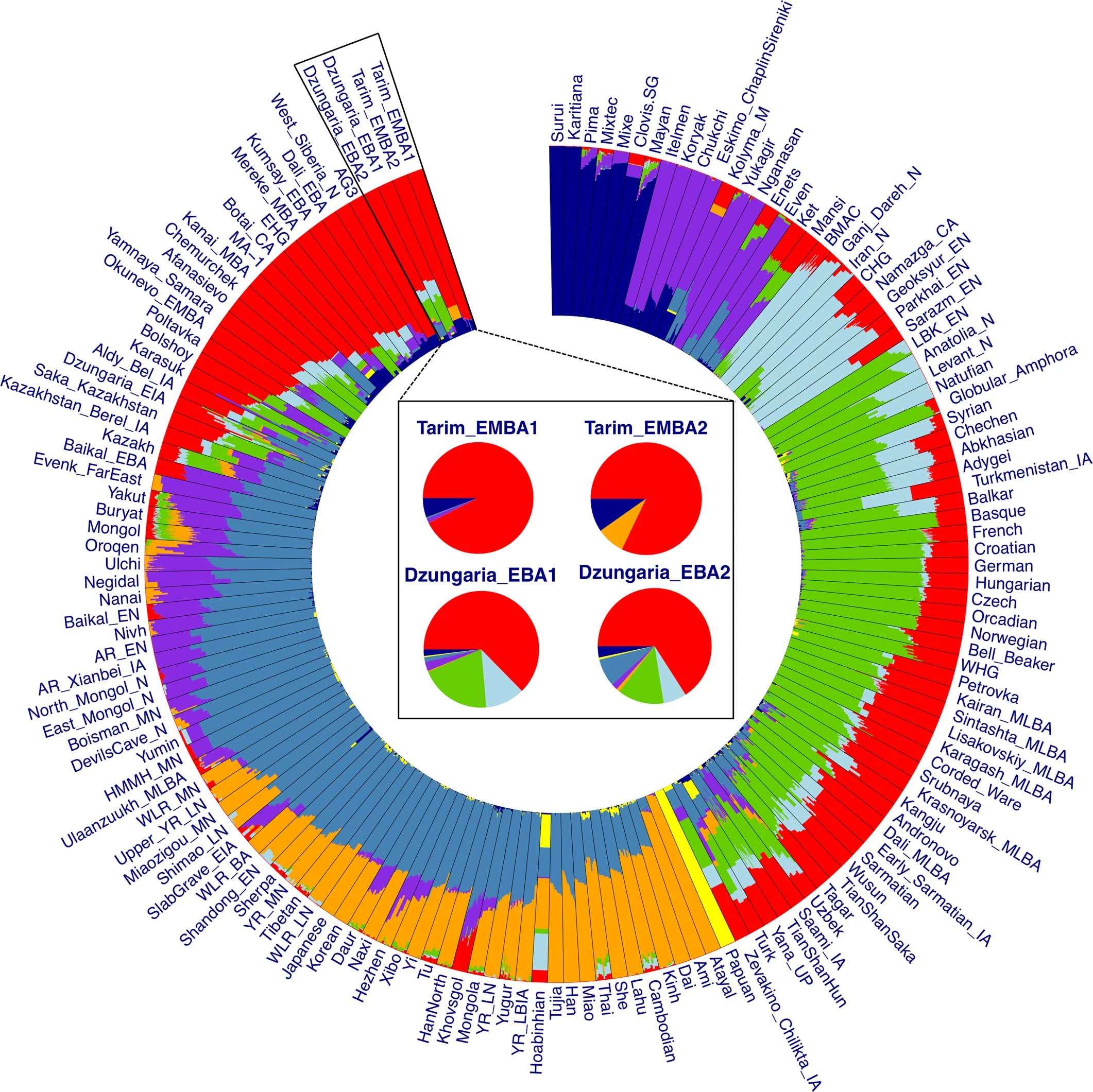

Extended Data Fig. 3 Unsupervised ADMIXTURE plot for the Bronze Age Xinjiang individuals.

Discussion

Although human activities in Xinjiang can be traced back to around 40,000 years ago24,39, the earliest evidence for sustained human habitation in the Tarim Basin dates only to the late third to early second millennium BC. There, at the sites of Xiaohe, Gumugou and Beifang, well-preserved mummified human remains buried within wooden coffins and associated with rich organic grave good assemblages represent the earliest known archaeological cultures of the region. Since their initial discovery in the early twentieth century and subsequent large-scale excavations beginning in the 1990s (ref. 16), the Tarim mummies have been at the centre of debates with regard to their origins, their relationship to other Bronze Age steppe (Afanasievo), oasis (BMAC) and mountain (IAMC and Chemurchek) groups, and their potential connection to the spread of Indo-European languages into this region3,4,40.

The palaeogenomic and proteomic data we present here suggest a very different and more complex population history than previously proposed. Although the IAMC may have been a vector for transmitting cultural and economic factors into the Tarim Basin, the known sites from the IAMC do not provide a direct source of ancestry for the Xiaohe populations. Instead, the Tarim mummies belong to an isolated gene pool whose Asian origins can be traced to the early Holocene epoch. This gene pool is likely to have once had a much wider geographic distribution, and it left a substantial genetic footprint in the EMBA populations of the Dzungarian Basin, IAMC and southern Siberia. The Tarim mummies’ so-called Western physical features are probably due to their connection to the Pleistocene ANE gene pool, and their extreme genetic isolation differs from the EBA Dzungarian, IAMC and Chemurchek populations, who experienced substantial genetic interactions with the nearby populations mirroring their cultural links, pointing towards a role of extreme environments as a barrier to human migration.

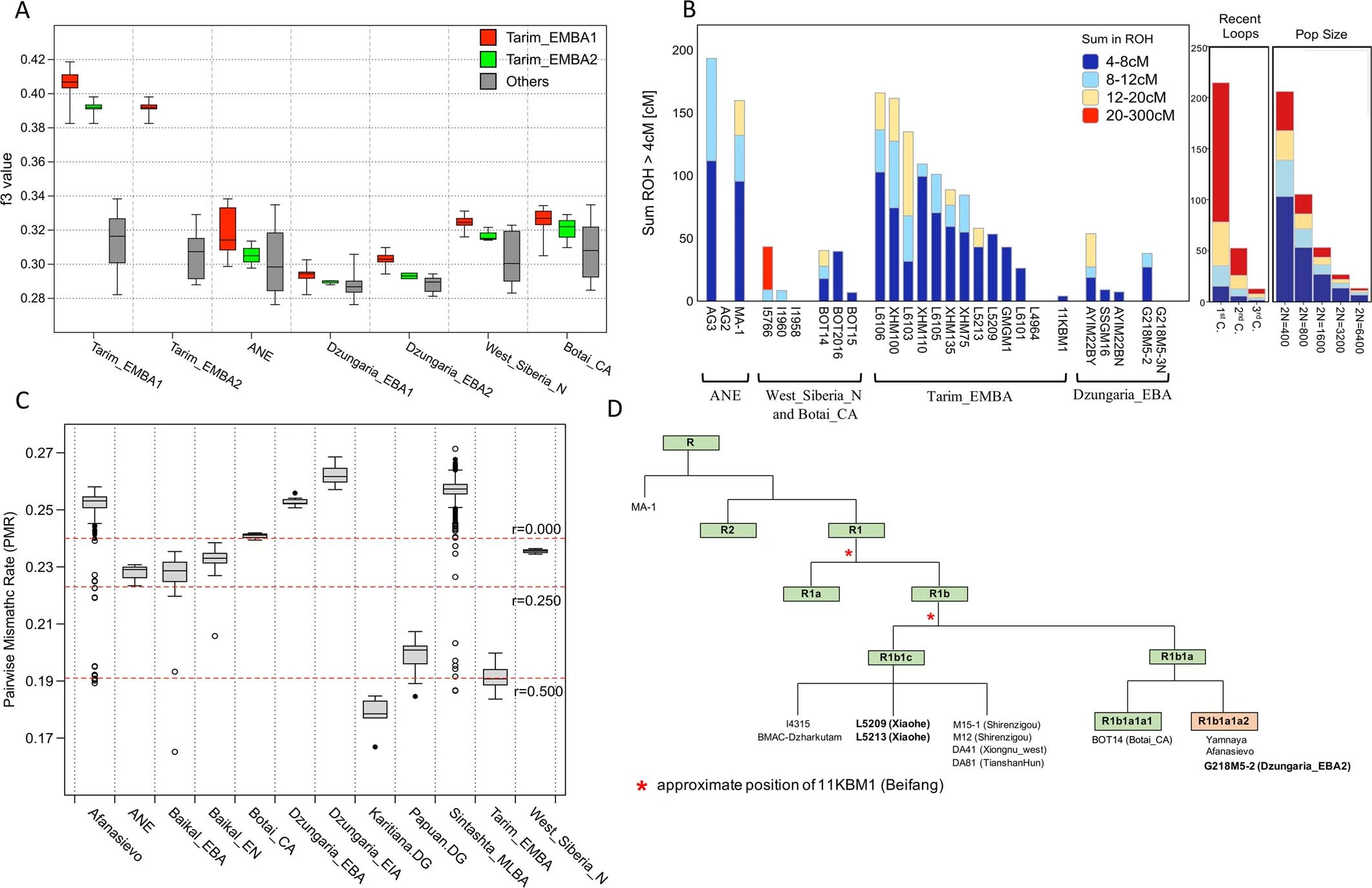

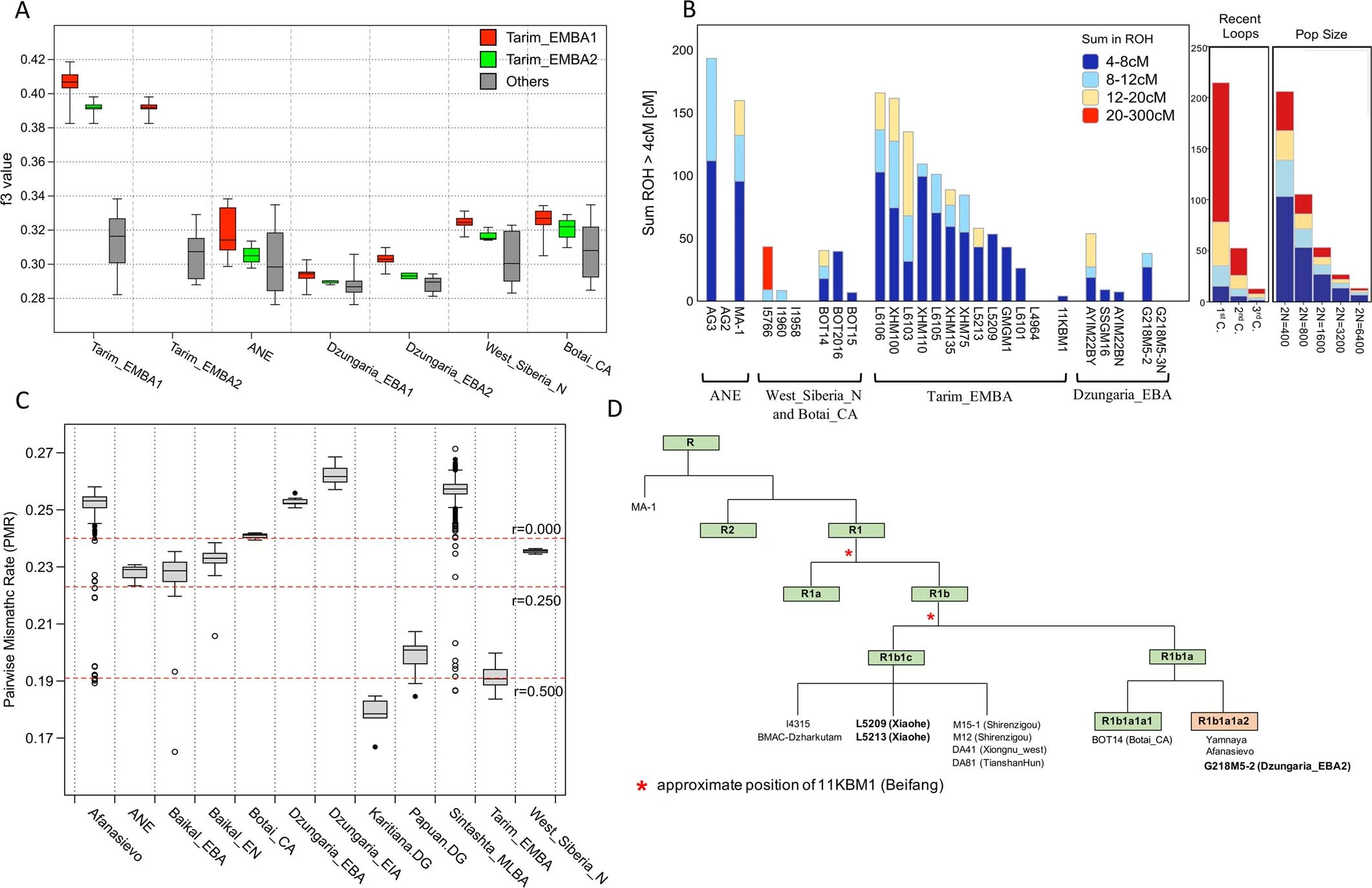

Extended Data Fig. 4 Reduced genetic diversity of the Tarim_EMBA individuals.

A, a comparison of individual outgroup f3-statistics for the ancient Xinjiang populations and their neighboring populations from Inner Asia, including Tarim_EMBA1 (n = 12), Tarim_EMBA2 (n = 1), ANE (n = 3), Dzungaria_EBA1 (n = 3), Dzungaria_EBA2 (n = 2), West_Siberia_N (n = 3) and Botai_CA (n = 3), which Tarim Basin individuals show the highest affinity to each other. In each boxplot, the box marks the 25th and 75th quartiles of the distribution, respectively, and the horizontal line within the box marks the median. The whisker delineates the maximum and the minimum. B, the cumulative distribution of ROH tracts shows that Tarim_EMBA individuals did not descend from close related parents. C, pairwise mismatch rate (pmr) between individuals in the ancient populations of Xinjiang and its neighboring regions, including all pairs of individuals within the Afanasievo (n = 27), ANE (n = 3), Baikal_EBA (n = 9), Baikal_EN (n = 15), Botai_CA (n = 3), Dzungaria_EBA (n = 5), Dzungaria_EIA (n = 10), Sintashta_MLBA (n = 51), Tarim_EMBA (n = 13), West_Siberia_N (n = 3), as well as present-day isolated populations such as Papuan and Karitiana. Tarim_EMBA individuals uniformly show a much reduced pmr value that is equivalent to the first-degree relatives in Afanasievo or Sintashta_MLBA. The red dotted lines mark the expected pmr value for the given coefficient of relationship (r), ranging from 0 (unrelated) and 1/4 (second degree relatives) to 1/2 (first degree relatives), based on the mean value of pmr among these populations, respectively. In each box plot, the box represents the interquartile range (the 25th and 75th quartiles), and the horizon line within the box represents the median. Black-filled and open circles represent outliers (1.5 times beyond the IQR) and extreme outliers (3 times beyond the IQR), respectively. The whisker delineates the smallest and the largest non-outlier observations. D, Y chromosome phylogeny of the Bronze Age Xinjiang male individuals. Xiaohe male individuals fall into a branch distinct from western Bronze Age steppe pastoralists, such as Afanasievo and Yamnaya. One individual from Beifang falls in a position that is more basal than Xiaohe, but its phylogenetic position cannot be fixed due to low coverage, and its proximate position(s) are instead indicated with an asterisk.

In contrast to their marked genetic isolation, however, the populations of the Xiaohe horizon were culturally cosmopolitan, incorporating diverse economic elements and technologies with far-flung origins. They made cheese from ruminant milk using a kefir-like fermentation37, perhaps learned from descendants of the Afanasievo, and they cultivated wheat, barley and millet37,41, crops that were originally domesticated in the Near East and northern China and which were introduced into Xinjiang no earlier than 3500 BC (refs. 8,42), probably via their IAMC neighbours24. They buried their dead with Ephedra twigs in a style reminiscent of the BMAC oasis cultures of Central Asia, and they also developed distinctive cultural elements not found among other cultures in Xinjiang or elsewhere, such as boat-shaped wooden coffins covered with cattle hides and marked by timber poles or oars, as well as an apparent preference for woven baskets over pottery43,44. Considering these findings together, it appears that the tightknit population that founded the Xiaohe horizon were well aware of different technologies and cultures outside the Tarim Basin and that they developed their unique culture in response to the extreme challenges of the Taklamakan Desert and its lush and fertile riverine oases4.

This study illuminates in detail the origins of the Bronze Age human populations in the Dzungarian and Tarim basins of Xinjiang. Notably, our results support no hypothesis involving substantial human migration from steppe or mountain agropastoralists for the origin of the Bronze Age Tarim mummies, but rather we find that the Tarim mummies represent a culturally cosmopolitan but genetically isolated autochthonous population. This finding is consistent with earlier arguments that the IAMC served as a geographic corridor and vector for regional cultural interaction that connected disparate populations from the fourth to the second millennium BC (refs. 24,25). While the arrival and admixture of Afanasievo populations in the Dzungarian Basin of northern Xinjiang around 3000 BC may have plausibly introduced Indo-European languages to the region, the material culture and genetic profile of the Tarim mummies from around 2100 BC onwards call into question simplistic assumptions about the link between genetics, culture and language and leave unanswered the question of whether the Bronze Age Tarim populations spoke a form of proto-Tocharian. Future archaeological and palaeogenomic research on subsequent Tarim Basin populations—and most importantly, studies of the sites and periods where first millennium AD Tocharian texts have been recovered—are necessary to understand the later population history of the Tarim Basin. Finally, the palaeogenomic characterization of the Tarim mummies has unexpectedly revealed one of the few known Holocene-era genetic descendant populations of the once widespread Pleistocene ANE ancestry profile. The Tarim mummy genomes thus provide a critical reference point for genetically modelling Holocene-era populations and reconstructing the population history of Asia.

Although the harsh environment of the Tarim Basin may have served as a strong barrier to gene flow into the region, it was not a barrier to the flow of ideas or technologies, as foreign innovations, such as dairy pastoralism and wheat and millet agriculture, came to form the basis of the Bronze Age Tarim economies. Woollen fabrics, horns and bones of cattle, sheep and goats, livestock manure, and milk and kefir-like dairy products have been recovered from the upper layers of the Xiaohe and Gumugou cemeteries33,34,35,36, as have wheat and millet seeds and bundles of Ephedra twigs34,37,38. Famously, many of the mummies dating to 1650–1450 BC were even buried with lumps of cheese35. However, until now it has not been clear whether this pastoralist lifestyle also characterized the earliest layers at Xiaohe.

To better understand the dietary economy of the earliest archaeological periods, we analysed the dental calculus proteomes of seven individuals at the site of Xiaohe dating to around 2000–1700 BC. All seven individuals were strongly positive for ruminant-milk-specific proteins (Extended Data Table 2), including β-lactoglobulin, α-S1-casein and α-lactalbumin (Extended Data Fig. 5), and peptide recovery was sufficient to provide taxonomically diagnostic matches to cattle (Bos), sheep (Ovis) and goat (Capra) milk (Extended Data Fig. 5, Extended Data Table 2 and Supplementary Data 3). These results confirm that dairy products were consumed by individuals of autochthonous ancestry (Tarim_EMBA1) buried in the lowest levels of the Xiaohe cemetery (Extended Data Table 2). Importantly, however, and in contrast to previous hypotheses36, none of the Tarim individuals was genetically lactase persistent (Supplementary Data 1J). Rather, the Tarim mummies contribute to a growing body of evidence that prehistoric dairy pastoralism in Inner and East Asia spread independently of lactase persistence genotypes28,30.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Unsupervised ADMIXTURE plot for the Bronze Age Xinjiang individuals.

Discussion

Although human activities in Xinjiang can be traced back to around 40,000 years ago24,39, the earliest evidence for sustained human habitation in the Tarim Basin dates only to the late third to early second millennium BC. There, at the sites of Xiaohe, Gumugou and Beifang, well-preserved mummified human remains buried within wooden coffins and associated with rich organic grave good assemblages represent the earliest known archaeological cultures of the region. Since their initial discovery in the early twentieth century and subsequent large-scale excavations beginning in the 1990s (ref. 16), the Tarim mummies have been at the centre of debates with regard to their origins, their relationship to other Bronze Age steppe (Afanasievo), oasis (BMAC) and mountain (IAMC and Chemurchek) groups, and their potential connection to the spread of Indo-European languages into this region3,4,40.

The palaeogenomic and proteomic data we present here suggest a very different and more complex population history than previously proposed. Although the IAMC may have been a vector for transmitting cultural and economic factors into the Tarim Basin, the known sites from the IAMC do not provide a direct source of ancestry for the Xiaohe populations. Instead, the Tarim mummies belong to an isolated gene pool whose Asian origins can be traced to the early Holocene epoch. This gene pool is likely to have once had a much wider geographic distribution, and it left a substantial genetic footprint in the EMBA populations of the Dzungarian Basin, IAMC and southern Siberia. The Tarim mummies’ so-called Western physical features are probably due to their connection to the Pleistocene ANE gene pool, and their extreme genetic isolation differs from the EBA Dzungarian, IAMC and Chemurchek populations, who experienced substantial genetic interactions with the nearby populations mirroring their cultural links, pointing towards a role of extreme environments as a barrier to human migration.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Reduced genetic diversity of the Tarim_EMBA individuals.

A, a comparison of individual outgroup f3-statistics for the ancient Xinjiang populations and their neighboring populations from Inner Asia, including Tarim_EMBA1 (n = 12), Tarim_EMBA2 (n = 1), ANE (n = 3), Dzungaria_EBA1 (n = 3), Dzungaria_EBA2 (n = 2), West_Siberia_N (n = 3) and Botai_CA (n = 3), which Tarim Basin individuals show the highest affinity to each other. In each boxplot, the box marks the 25th and 75th quartiles of the distribution, respectively, and the horizontal line within the box marks the median. The whisker delineates the maximum and the minimum. B, the cumulative distribution of ROH tracts shows that Tarim_EMBA individuals did not descend from close related parents. C, pairwise mismatch rate (pmr) between individuals in the ancient populations of Xinjiang and its neighboring regions, including all pairs of individuals within the Afanasievo (n = 27), ANE (n = 3), Baikal_EBA (n = 9), Baikal_EN (n = 15), Botai_CA (n = 3), Dzungaria_EBA (n = 5), Dzungaria_EIA (n = 10), Sintashta_MLBA (n = 51), Tarim_EMBA (n = 13), West_Siberia_N (n = 3), as well as present-day isolated populations such as Papuan and Karitiana. Tarim_EMBA individuals uniformly show a much reduced pmr value that is equivalent to the first-degree relatives in Afanasievo or Sintashta_MLBA. The red dotted lines mark the expected pmr value for the given coefficient of relationship (r), ranging from 0 (unrelated) and 1/4 (second degree relatives) to 1/2 (first degree relatives), based on the mean value of pmr among these populations, respectively. In each box plot, the box represents the interquartile range (the 25th and 75th quartiles), and the horizon line within the box represents the median. Black-filled and open circles represent outliers (1.5 times beyond the IQR) and extreme outliers (3 times beyond the IQR), respectively. The whisker delineates the smallest and the largest non-outlier observations. D, Y chromosome phylogeny of the Bronze Age Xinjiang male individuals. Xiaohe male individuals fall into a branch distinct from western Bronze Age steppe pastoralists, such as Afanasievo and Yamnaya. One individual from Beifang falls in a position that is more basal than Xiaohe, but its phylogenetic position cannot be fixed due to low coverage, and its proximate position(s) are instead indicated with an asterisk.

In contrast to their marked genetic isolation, however, the populations of the Xiaohe horizon were culturally cosmopolitan, incorporating diverse economic elements and technologies with far-flung origins. They made cheese from ruminant milk using a kefir-like fermentation37, perhaps learned from descendants of the Afanasievo, and they cultivated wheat, barley and millet37,41, crops that were originally domesticated in the Near East and northern China and which were introduced into Xinjiang no earlier than 3500 BC (refs. 8,42), probably via their IAMC neighbours24. They buried their dead with Ephedra twigs in a style reminiscent of the BMAC oasis cultures of Central Asia, and they also developed distinctive cultural elements not found among other cultures in Xinjiang or elsewhere, such as boat-shaped wooden coffins covered with cattle hides and marked by timber poles or oars, as well as an apparent preference for woven baskets over pottery43,44. Considering these findings together, it appears that the tightknit population that founded the Xiaohe horizon were well aware of different technologies and cultures outside the Tarim Basin and that they developed their unique culture in response to the extreme challenges of the Taklamakan Desert and its lush and fertile riverine oases4.

This study illuminates in detail the origins of the Bronze Age human populations in the Dzungarian and Tarim basins of Xinjiang. Notably, our results support no hypothesis involving substantial human migration from steppe or mountain agropastoralists for the origin of the Bronze Age Tarim mummies, but rather we find that the Tarim mummies represent a culturally cosmopolitan but genetically isolated autochthonous population. This finding is consistent with earlier arguments that the IAMC served as a geographic corridor and vector for regional cultural interaction that connected disparate populations from the fourth to the second millennium BC (refs. 24,25). While the arrival and admixture of Afanasievo populations in the Dzungarian Basin of northern Xinjiang around 3000 BC may have plausibly introduced Indo-European languages to the region, the material culture and genetic profile of the Tarim mummies from around 2100 BC onwards call into question simplistic assumptions about the link between genetics, culture and language and leave unanswered the question of whether the Bronze Age Tarim populations spoke a form of proto-Tocharian. Future archaeological and palaeogenomic research on subsequent Tarim Basin populations—and most importantly, studies of the sites and periods where first millennium AD Tocharian texts have been recovered—are necessary to understand the later population history of the Tarim Basin. Finally, the palaeogenomic characterization of the Tarim mummies has unexpectedly revealed one of the few known Holocene-era genetic descendant populations of the once widespread Pleistocene ANE ancestry profile. The Tarim mummy genomes thus provide a critical reference point for genetically modelling Holocene-era populations and reconstructing the population history of Asia.