|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 27, 2018 18:47:13 GMT

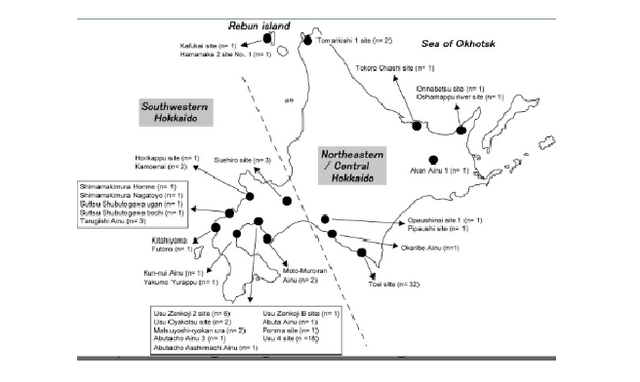

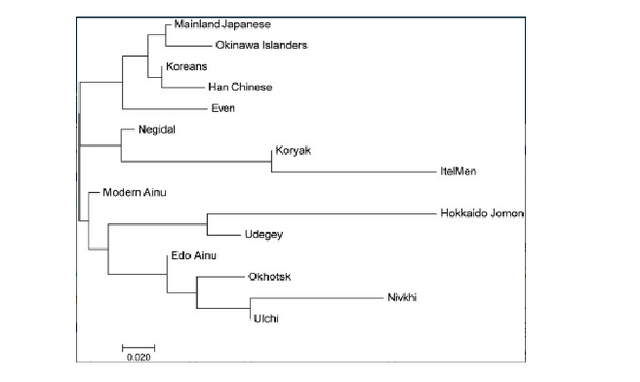

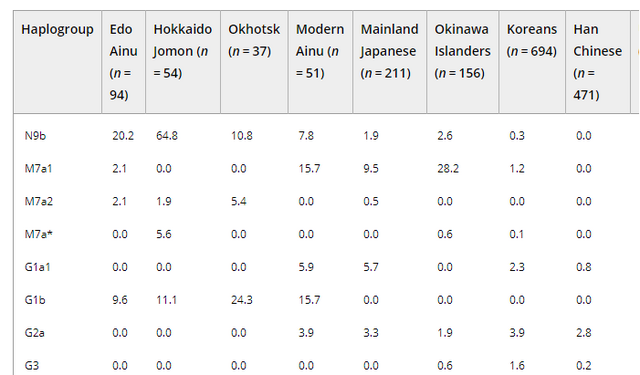

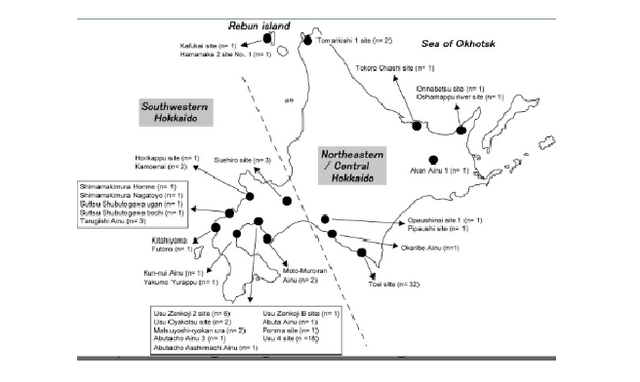

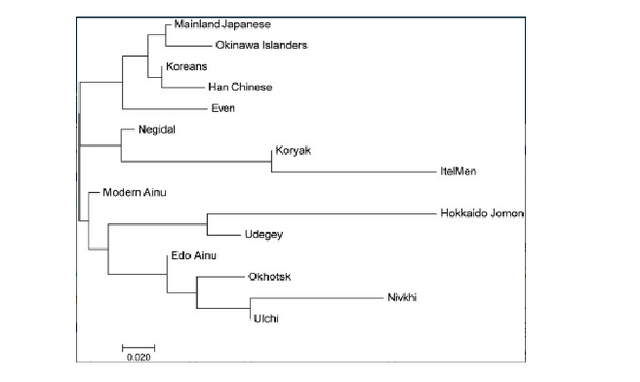

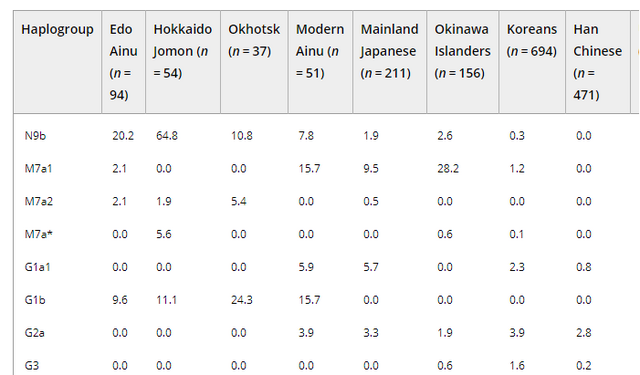

Figure 3. Regional classification of the population sample sites. Geographic locations of the sites are indicated by black dots. Numbers in parentheses denote the numbers of samples from each site that were successfully analyzed As described earlier, previous morphological studies have indicated possible regional differences in the Ainu people. These studies divided Hokkaido Island in several different ways. Among them, Dodo et al. (2012) explicitly explained their particular system of division as follows. The area that is southwest of Ishikari Low Land (southwestern Hokkaido, classified by the dashed line in Figure 3) often shared the same culture as the northern part of Honshu since the Jomon era. Moreover, the influence of the Kofun culture of northern Honshu, which played an important role in the formation of the Satsumon culture, extended into this area. Therefore, this area is expected to have been genetically more influenced by the mainland Japanese than the other areas of Hokkaido. On the other hand, the area along the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk was intensively inhabited by the Okhotsk culture people; therefore, their influence is expected to be more evident in this area. The other area is considered to be less influenced by mainland Japanese and the Okhotsk people, and is expected to have retained the characteristics of the indigenous Jomon people. We adopted this classification and analyzed the observed haplogroups in each region and their frequencies to elucidate the regional differences of the Ainu. However, the number of samples from along the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk that were successfully analyzed was small (seven individuals from four sites, see Figure 3), so we combined this area with the central area and analyzed this as “northeastern/central Hokkaido.” Aside from the Hokkaido Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people, the populations inhabiting the neighboring area of Hokkaido are expected to have contributed to the establishment of the Ainu. Therefore, to elucidate the regional differences of the haplogroups observed in the Edo Ainu, we classified them into four types as follows: (1) Hokkaido Jomon type (the haplogroups that are observed in the Hokkaido Jomon); (2) Okhotsk type (the haplogroups that are observed in the Okhotsk culture people, but are absent from the Hokkaido Jomon); (3) mainland Japanese type (the haplogroups that are absent from the Hokkaido Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people, but are observed in modern-day mainland Japanese at higher frequencies than in modern-day native Siberians); and (4) Siberian type (the haplogroups that are absent from the Hokkaido Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people, but are observed in modern-day native Siberians at higher frequencies than in modern-day mainland Japanese). Based on the frequencies of these four haplogroup types, regional differences of the Ainu between southwestern Hokkaido and northeastern/central Hokkaido were examined by Fisher's exact probability test by using R version 3.4.1 (R Core Team, 2017).  Genetic characteristics of the Ainu mtDNAs Twenty-one haplogroups and their subhaplogroups were identified in 94 Edo Ainu individuals (Supporting Information Table S1). As described earlier, conventionally, the Ainu are considered to be descended from the Hokkaido Jomon people, with little admixture with other populations. Among the haplogroups observed in the Hokkaido Jomon (N9b1, N9b4, N9b*, D4h2, G1b*, M7a2, M7a*; Adachi et al., 2011), haplogroups N9b1, G1b*, and M7a2 are also observed in the Edo Ainu. Above all, haplogroup N9b1, which is the most frequently observed haplogroup in the Hokkaido Jomon people (55.6%, 30 of 54 individuals; Adachi et al., 2011), is also observed at a relatively high frequency (20.2%, 19 of 94 individuals) in the Edo Ainu. These findings indicate the genetic continuity between the Hokkaido Jomon and the Ainu. This possible genetic continuity is corroborated by Y chromosome DNA analysis of the modern Ainu. Y chromosomal DNA haplogroup D1b, which is considered to be a strong candidate for the Jomon paternal lineage, was observed at high frequency in the modern Ainu (Hammer et al., 2006; Tajima et al., 2004). However, there is a crucial difference between the Hokkaido Jomon people and the Ainu. Four haplogroups (N9b4, N9b*, D4h2, M7a*) are missing in the Edo Ainu, whereas they have 19 haplogroups that are not observed in the Hokkaido Jomon. This raises questions about the conventional hypothesis that the Ainu are the direct descendants of the Hokkaido Jomon people. To clarify the matrilineal genetic relationship between the Edo Ainu and the other populations, pairwise Fst values between each pair of populations (Supporting Information Table S2) were calculated from the mtDNA haplogroup frequencies of the Edo Ainu and the 14 ancient and modern-day East Asian and Siberian populations (Table 1, Figure 1). In the frequency-based clustering of compared populations determined by neighbor-joining based on the Fst values described earlier, the Ainu of the Edo era was located almost in the median center between the Hokkaido Jomon/Udegey cluster and the Lower Amur region cluster including the Okhotsk culture people (Figure 4). This confirmed our hypothesis (Adachi et al., 2011) that the genetic characteristics of the Ainu are based on the Hokkaido Jomon people and the subsequent input of Lower Amur region Siberian genes through the Okhotsk culture people. However, when examining in detail the haplogroups observed in the Ainu examined in the present study, haplogroups M7a1, M7b1a1a1, D4 (except for D4h2), M8a, Z1a, M9a, F1b, N9a, A5a, and A5c are observed neither in the Hokkaido Jomon nor in the Okhotsk culture people. This suggests the presence of populations other than the Hokkaido Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people that contributed to the formation of the Ainu. Mainland Japanese and the native Siberians are considered to be the major candidates for the origin of these haplogroups because of the proximity of their distributions to Hokkaido. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 29, 2018 18:50:25 GMT

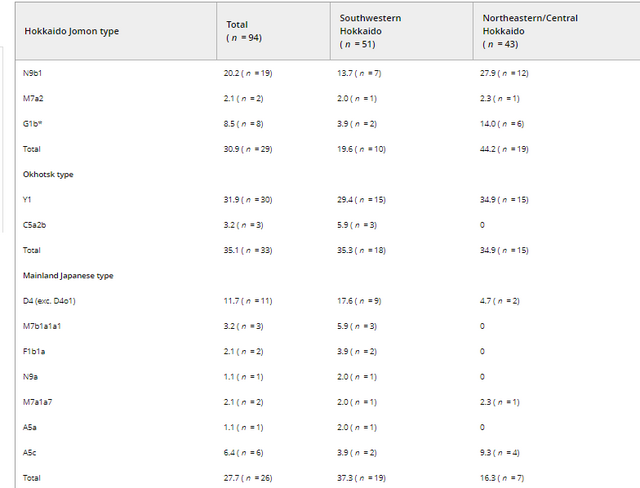

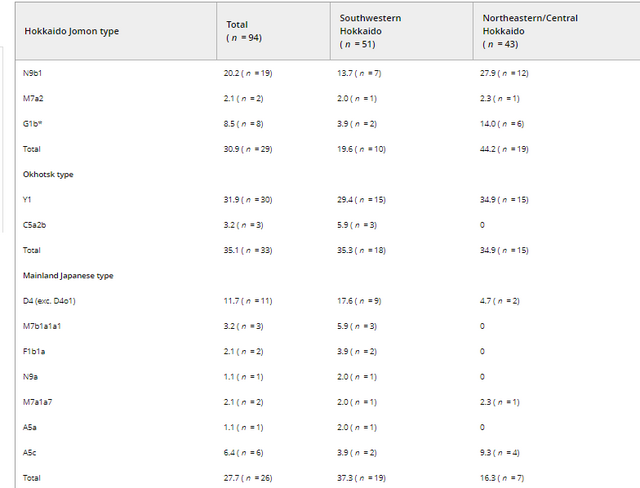

Figure 4. Frequency-based clustering of 15 ancient and modern East Asian and Siberian populations determined by neighbor-joining using the Fst values based on haplogroup frequencies Ethnic derivation of the Ainu inferred from mtDNA data As widely recognized, mtDNA provides only matrilineal information of the populations. Moreover, it covers only a tiny portion of genetic variation of the individual and is very prone to genetic drift. Therefore, many of the population parameters examined in the present study must be interpreted cautiously. We tried to shed as much light as possible on the genetic features of the Ainu despite these restrictions. Nowadays, among the theories explaining the population history of the Japanese, the dual-structure model proposed by Hanihara (1991) is the most widely accepted. This model assumes that the first occupants of the Japanese archipelago came from somewhere in Southeast Asia and they gave rise to the Jomon people. Thereafter, the second wave of migration from Northeast Asia took place in and after the Aeneolithic Yayoi age. These two populations gradually mixed with each other and brought the Japanese people into existence. In this model, the Ainu are considered to be descended from the Jomon people, with little admixture with other populations. However, the results of our study suggest that the later admixture of Ainu with other populations than Jomon people was more considerable than it was proposed until today.  Table 2. Frequencies of the four types of mtDNA haplogroups (%) observed in the Edo Ainu in each region First, our results showed that the genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people on the Ainu is significant. The proportion of Okhotsk-type haplogroups in the Edo Ainu was 35.1%, which is as high as that of the Jomon-type haplogroups (30.9%). This suggests that the Okhotsk culture people were one of the main genetic contributors to the formation of the Ainu. Moreover, intriguingly, a genetic contribution of the mainland Japanese to the Edo Ainu is evident (28.1%), which is almost as considerable as those of the Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people. As referred to above, conventionally, the genetic influence of the mainland Japanese on the Ainu is considered to have been limited until the Meiji government started sending settlers to Hokkaido as a national policy in 1869. However, our findings cast doubt on this accepted notion. In addition, Siberian-type haplogroups are observed in the Edo Ainu. Although their frequency is low (7.3%), as described earlier, the existence of these haplogroups may hint at the continuity of the genetic relationship between the Ainu and native Siberians even after the Okhotsk culture disappeared from Hokkaido. However, the number of Okhotsk people who were genetically analyzed is still small (n = 37; Sato et al., 2009), so it is possible that these haplogroups will be identified in the Okhotsk people in further study. By classifying the mtDNA haplogroups into four types as described earlier, regional differences of the Ainu people were highlighted. Judging from the data shown in Table 2, the high frequencies of Jomon-type haplogroups in northeastern/central Hokkaido (44.2%) and the high frequencies of mainland Japanese-type haplogroups in southwestern Hokkaido (37.3%) might be plausible reasons for these regional differences. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Mar 31, 2018 18:48:31 GMT

As widely recognized, mtDNA provides only matrilineal information of the populations. Moreover, it covers only a tiny portion of genetic variation of the individual and is very prone to genetic drift. Therefore, many of the population parameters examined in the present study must be interpreted cautiously. We tried to shed as much light as possible on the genetic features of the Ainu despite these restrictions. Nowadays, among the theories explaining the population history of the Japanese, the dual‐structure model proposed by Hanihara (1991) is the most widely accepted. This model assumes that the first occupants of the Japanese archipelago came from somewhere in Southeast Asia and they gave rise to the Jomon people. Thereafter, the second wave of migration from Northeast Asia took place in and after the Aeneolithic Yayoi age. These two populations gradually mixed with each other and brought the Japanese people into existence. In this model, the Ainu are considered to be descended from the Jomon people, with little admixture with other populations. However, the results of our study suggest that the later admixture of Ainu with other populations than Jomon people was more considerable than it was proposed until today.  First, our results showed that the genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people on the Ainu is significant. The proportion of Okhotsk‐type haplogroups in the Edo Ainu was 35.1%, which is as high as that of the Jomon‐type haplogroups (30.9%). This suggests that the Okhotsk culture people were one of the main genetic contributors to the formation of the Ainu. Moreover, intriguingly, a genetic contribution of the mainland Japanese to the Edo Ainu is evident (28.1%), which is almost as considerable as those of the Jomon and the Okhotsk culture people. As referred to above, conventionally, the genetic influence of the mainland Japanese on the Ainu is considered to have been limited until the Meiji government started sending settlers to Hokkaido as a national policy in 1869. However, our findings cast doubt on this accepted notion. In addition, Siberian‐type haplogroups are observed in the Edo Ainu. Although their frequency is low (7.3%), as described earlier, the existence of these haplogroups may hint at the continuity of the genetic relationship between the Ainu and native Siberians even after the Okhotsk culture disappeared from Hokkaido. However, the number of Okhotsk people who were genetically analyzed is still small (n = 37; Sato et al., 2009), so it is possible that these haplogroups will be identified in the Okhotsk people in further study. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Apr 2, 2018 18:31:07 GMT

By classifying the mtDNA haplogroups into four types as described earlier, regional differences of the Ainu people were highlighted. Judging from the data shown in Table 2, the high frequencies of Jomon‐type haplogroups in northeastern/central Hokkaido (44.2%) and the high frequencies of mainland Japanese‐type haplogroups in southwestern Hokkaido (37.3%) might be plausible reasons for these regional differences. This result is consistent with the result of a morphological analysis by Ossenberg et al. (2006). They described that, among the Ainu in Hokkaido, individuals in southeastern Hokkaido (this area is contained within our category of “northeastern/central Hokkaido”) are the closest to the Jomon people, whereas the individuals in western Hokkaido (this area is included within our category of “southwestern Hokkaido”) are the closest to mainland Japanese. This result is considered reasonable, given the geographical proximity of southwestern Hokkaido to the main island of Japan.  However, surprisingly, there were no regional differences in the frequencies of the Okhotsk‐type haplogroups (35.3% in southwestern Hokkaido and 34.9% in northeastern/central Hokkaido). This indicates that the genetic influence of the Okhotsk culture people diffused rapidly in the fledgling Ainu. As described earlier, Segawa (2007) stated that the invasion of the Satsumon culture people into the areas inhabited by the Okhotsk culture people and the subsequent decline of Okhotsk culture occurred rapidly. The Okhotsk culture people were considered to have been assimilated rapidly into the Satsumon culture during this process, and became part of the basis of the Ainu. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.23338 |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on Jul 4, 2018 18:49:59 GMT

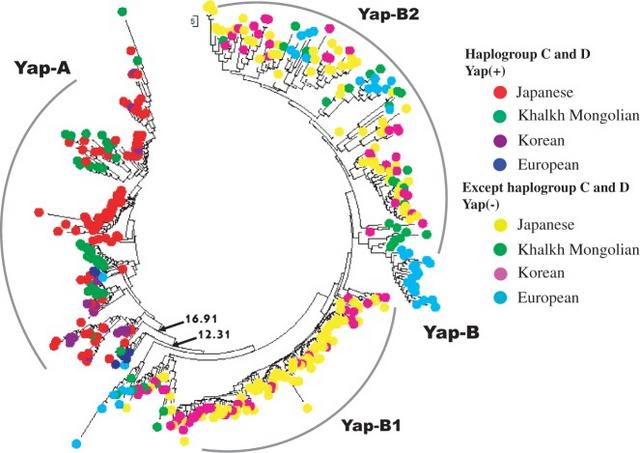

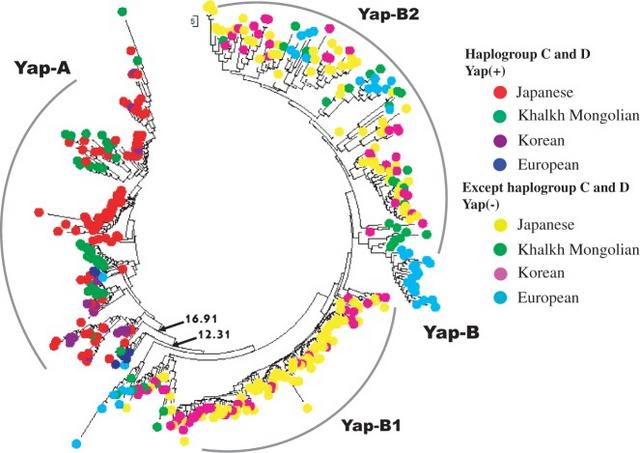

The study of human evolution has benefited from the development of genome-wide approaches to obtaining molecular data. However, most genes in the genome do not evolve fast enough for the study of human evolution at the level of direct sequence comparisons, for which reason short tandem repeat (STR) markers on the Y chromosome (Y-STR) and mitochondrial DNA sequence (mtDNA), both of which evolve faster than autosomal loci, are useful in human evolution studies. Those two types of sequences also permit the independent study of male and female lineage divergences. Y-STR and mtDNA data have thus contributed to elucidating many aspects of human evolution (Cann et al. 1987; Excoffier et al. 1987; Bowcock et al. 1991; Horai 1991; Excoffier et al. 1992; Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994; Hammer and Horai 1995; Zerjal et al. 1997; Bergen et al. 1999; Shinka et al. 1999; Tanaka et al. 2004; Katoh et al. 2005a; Derenko et al. 2007). In addition, while Ingman et al. (2000) and Maca-Meyer et al. (2001) have shown that mtDNA sequences are still appropriate for the studies of global human diversity, Katoh et al. (2005b) demonstrated the usefulness of Y-STR for the evolutionary study of East Asian ethnic groups. However, those studies have lacked resolution for individual lineages and have not provided coherent pictures of male and female lineage splittings. Indeed, a major issue in human evolution is that the study of the male lineage delivers results that differ from those obtained through the study of the female lineage (Underhill and Kivisild 2007). Therefore, we focused in the present study on examining human evolution at the level of males and females separately. Our interest focused on the divergence of three major populations—Africans, Europeans, and East Asians—and East Asians and Europeans in particular, because they lived together for a while after coming out of Africa and likely interbred, perhaps similar to the hybridizations reported between Neanderthals and modern humans (Noonan 2006). After the divergence between Mongoloid (East Asian) and Caucasoid (European) people ∼55,000 years ago (Nei and Roychoudhury 1993), they might have still interbred while en route to settlement in their present localities.  Fig. 1.— Phylogenetic tree of Yap haplotypes for Europeans and East Asians. The tree was constructed by using the Y-STR data, and the Yap haplotypes were placed at the tips of the tree. To investigate this, we sampled a number of European and East Asian individuals to obtain information on the male and female lineages, by constructing phylogenetic trees based on Y-STR and mtDNA sequences, respectively. These two trees should provide new information on the divergence of the East Asian and European lineages. We included in our study data from the Ainu people in the northmost island of the Japanese archipelago, because their ancestor and evolutionary history are still obscure. Recently, Jinam et al. (2012) suggested that the Ainu are closer to the people in Okinawa from the southmost archipelago in Japan than they are to any other East Asian people. Our investigation also addresses Ainu origin. To study the female lineages we collected the complete mtDNA genomes (16,750 bp each) from the International Nucleotide Sequence Data Collaboration (DDBJ/ EMBL/GenBank) to study the female lineage of the European and East Asian. The mtDNA genome data include 32 Japanese, 11 Korean, 5 Mongolian, 23 European, and 1 African samples (table 1). For the mtDNA tree the evolutionary distance between a pair of individuals was obtained by the Kimura two-parameter method (Kimura 1980). The bootstrap test (Felsenstein 1985) was performed for 1,000 replicates for each tree (fig. 2). The African sample was used as the reference in the phylogenetic trees. |

|