|

|

Post by Admin on May 4, 2018 18:28:10 GMT

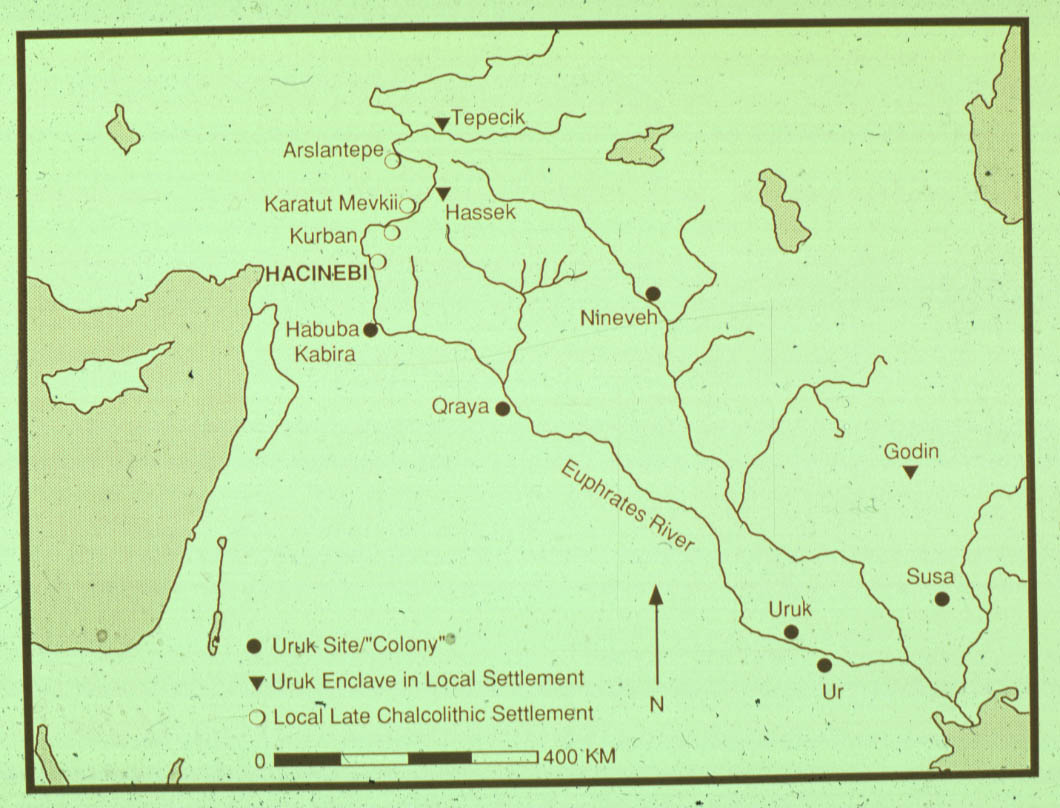

THE FIRST CITIES AND THEIR CONNECTION TO THE STEPPES Steppe contact with the civilizations of Mesopotamia was, of course, much less direct than contact with Tripolye societies, but the southern door might have been the avenue through which wheeled vehicles first appeared in the steppes, so it was important. Our understanding of these contacts with the south has been completely rewritten in recent years. Between 3700 and 3500 BCE the first cities in the world appeared among the irrigated lowlands of Mesopotamia. Old temple centers like Uruk and Ur had always been able to attract thousands of laborers from the farms of southern Iraq for building projects, but we are not certain why they began to live around the temples permanently (figure 12.8). This shift in population from the rural villages to the major temples created the first cities. During the Middle and Late Uruk periods (3700–3100 BCE) trade into and out of the new cities increased tremendously in the form of tribute, gift exchange, treaty making, and the glorification of the city temple and its earthly authorities.  Precious stones, metals, timber, and raw wool were among the imports. Woven textiles and manufactured metal objects probably were among the exports. During the Late Uruk period, wheeled vehicles pulled by oxen appeared as a new technology for land transport. New accounting methods were developed to keep track of imports, exports, and tax payments—cylinder seals for marking sealed packages and the sealed doors of storerooms, clay tokens indicating package contents, and, ultimately, writing. The new cities had enormous appetites for copper, gold, and silver. Their agents began an extraordinary campaign, or perhaps competing campaigns by different cities, to obtain metals and semiprecious stones. The native chiefdoms of Eastern Anatolia already had access to rich deposits of copper ore, and had long been producing metal tools and weapons.  Emissaries from Uruk and other Sumerian cities began to appear in northern cities like Tell Brak and Tepe Gawra. South Mesopotamian garrisons built and occupied caravan forts on the Euphrates in Syria at Habubu Kabira. The “Uruk expansion” began during the Middle Uruk period about 3700 BCE and greatly intensified during Late Uruk, about 3350–3100 BCE. The city of Susa in southwestern Iran might have become an Uruk colony. East of Susa on the Iranian plateau a series of large mudbrick edifices rose above the plains, protecting specialized copper production facilities that operated partly for the Uruk trade, regulated by local chiefs who used the urban tools of trade management: seals, sealed packages, sealed storerooms, and, finally, writing. Copper, lapis lazuli, turquoise, chlorite, and carnelian moved under their seals to Mesopotamia. Uruk-related trade centers on the Iranian plateau included Sialk IV1, Tal-i-Iblis V–VI, and Hissar II in central Iran. The tentacles of trade reached as far northeast as the settlement of Sarazm in the Zerafshan Valley of modern Tajikistan, probably established to control turquoise deposits in the deserts nearby. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 5, 2018 18:48:04 GMT

The Uruk expansion to the northwest, toward the gold, silver, and copper sources in the Caucasus Mountains, is documented at two important local strongholds on the upper Euphrates. Hacinebi was a fortified center with a large-scale copper production industry. Its chiefs began to deal with Middle Uruk traders during its phase B2, dated about 3700–3300 BCE. More than 250 km farther up the Euphrates, high in the mountains of Eastern Anatolia, the stronghold at Arslantepe expanded in wealth and size at about the same time (Phase VII), although it retained its own native system of seals, architecture, and administration. It also had its own large-scale copper production facilities based on local ores. Phase VIA, beginning about 3350 BCE, was dominated by two new pillared buildings similar to Late Uruk temples. In them officials regulated trade using some Uruk-style seals (among many local-style seals) and gave out stored food in Uruk-type, mass-produced ration bowls. The herds of Arslantepe VII had been dominated by cattle and goats, but in phase VIA sheep rose suddenly to become the most numerous and important animal, probably for the new industry of wool production. Horses also appeared, in very small numbers, at Arslantepe VII and VIA and Hacinebi phase B, but they seem not to have been traded southward into Mesopotamia. The Uruk expansion ended abruptly about 3100 BCE for reasons that remain obscure. Arslantepe and Hacinebi were burned and destroyed, and in the mountains of eastern Anatolia local Early Trans-Caucasian (ETC) cultures built their humble homes over the ruins of the grand temple buildings.21  Societies in the mountains to the north of Arslantepe responded in various ways to the general increase in regional trade that began about 3700–3500 BCE. Novel kinds of public architecture appeared. At Berikldeebi, northwest of modern Tbilisi in Georgia, a settlement that had earlier consisted of a few flimsy dwellings and pits was transformed about 3700–3500 BCE by the construction of a massive mudbrick wall that enclosed a public building, perhaps a temple, measuring 14.5 × 7.5 m (50 × 25 ft). At Sos level Va near Erzerum in northeastern Turkey there were similar architectural hints of increasing scale and power.22 But neither prepares us for the funerary splendor of the Maikop culture. The Maikop culture appeared about 3700–3500 BCE in the piedmont north of the North Caucasus Mountains, overlooking the Pontic-Caspian steppes. The remi-royal figure buried under the giant Maikop chieftan’s kurgan acquired and wore Mesopotamian ornaments in an ostentatious funeral display that had no parallel that has been preserved even in Mesopotamia. Into the grave went a tunic covered with golden lions and bulls, silversheathed staffs mounted with solid gold and silver bulls, and silver sheet-metal cups. Wheel-made pottery was imported from the south, and the new technique was used to make Maikop ceramics similar to some of the vessels found at Berikldeebi and at Arslantepe VII/VIA.23 New high-nickel arsenical bronzes and new kinds of bronze weapons (sleeved axes, tanged daggers) also spread into the North Caucasus from the south, and a cylinder seal from the south was worn as a bead in another Maikop grave. What kinds of societies lived in the North Caucasus when this contact began? |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 6, 2018 18:38:51 GMT

THE NORTH CAUCASUS PIEDMONT: ENEOLITHIC FARMERS BEFORE MAIKOP The North Caucasian piedmont separates naturally into three geographic parts. The western part is drained by the Kuban River, which flows into the Sea of Azov. The central part is a plateau famous for its bubbling hot springs, with resort towns like Mineralnyi Vody (Mineral Water) and Kislovodsk (Sweet Water). The eastern part is drained by the Terek River, which flows into the Caspian Sea. The southern skyline is dominated by the permanently glaciated North Caucasus Mountains, which rise to icy peaks more than 5,600 m (18,000 ft) high; and off to the north are the rolling brown plains of the steppes. Herding, copper-using cultures lived here by 5000 BCE. The Early Eneolithic cemetery at Nalchik and the cave occupation at Kammenomost Cave (chapter 9) date to this period. Beginning about 4400–4300 BCE the people of the North Caucasus began to settle in fortified agricultural villages such as Svobodnoe and Meshoko (level 1) in the west, Zamok on the central plateau, and Ginchi in Dagestan in the east, near the Caspian. About ten settlements of the Svobodnoe type, of thirty to forty houses each, are known in the Kuban River drainage, apparently the most densely settled region. Their earthen or stone walls enclosed central plazas surrounded by solid wattle-and-daub houses. Svobodnoe, excavated by A. Nekhaev, is the best-reported site (figure 12.9). Half the animal bones from Svobodnoe were from wild red deer and boar, so hunting was important. Sheep were the most important domesticated animal, and the proportion of sheep to goats was 5:1, which suggests that sheep were kept for wool. But pig keeping also was important, and pigs were the most important meat animals at the settlement of Meshoko.  Svobodnoe pots were brown to orange in color and globular with everted rims, but decorative styles varied greatly between sites (e.g., Zamok, Svobodnoe, and Meshoko are said to have had quite different domestic pottery types). Female ceramic figurines suggest female-centered domestic rituals. Bracelets carved and polished of local serpentine were manufactured in the hundreds at some sites. Cemeteries are almost unknown, but a few individual graves found among later graves under kurgans in the Kuban region have been ascribed to the Late Eneolithic. The Svobodnoe culture differed from Repin or late Khvalynsk steppe cultures in its house forms, settlement types, pottery, stone tools, and ceramic female figurines. Probably it was distinct ethnically and linguistically.24 |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 7, 2018 18:25:22 GMT

THE MAIKOP CULTURE The shift from Svobodnoe to Maikop was accompanied by a sudden change in funeral customs—the clear and widespread adoption of kurgan graves—but there was continuity in settlement locations and settlement types, lithics, and some aspects of ceramics. Early Maikop ceramics showed some similarities with Svobodnoe pot shapes and clay fabrics, and some similarities with the ceramics of the Early Trans-Caucasian (ETC) culture south of the North Caucasus Mountains. These analogies indicate that Maikop developed from local Caucasian origins. But some Maikop pots were wheel-made, a new technology introduced from the south, and this new method of manufacture probably encouraged new vessel shapes. The Maikop chieftain’s grave, discovered on the Belaya River, a tributary of the Kuban River, was the first Maikop-culture tomb to be excavated, and it remains the most important early Maikop site. When excavated in 1897 by N. I. Veselovskii, the kurgan was almost 11 m high and more than 100 m in diameter. The earthen center was surrounded by a cromlech of large undressed stones. Externally it looked like the smaller Mikhailovka I and Post-Mariupol kurgans (and, before them, the Suvorovo kurgans), which also had earthen mounds surrounded by stone cromlechs. Internally, however, the Maikop chieftan’s grave was quite different. The grave chamber was more than 5 m long and 4 m wide, 1.5 m deep, and was lined with large timbers. It was divided by timber partitions into two northern chambers and one southern chamber. The two northern chambers each held an adult female, presumably sacrificed, each lying in a contracted position on her right side, oriented southwest, stained with red ochre, with one to four pottery vessels and wearing twisted silver foil ornaments.25  The southern chamber contained an adult male. He also probably was positioned on his right side, contracted, with his head oriented southwest, the pose of most Maikop burials. He also lay on ground deeply stained with red ochre. With him were eight red-burnished, globular pottery vessels, the type collection for Early Maikop; a polished stone cup with a sheet-gold cover; two arsenical bronze, sheet-metal cauldrons; two small cups of sheet gold; and fourteen sheet-silver cups, two of which were decorated with impressed scenes of animal processions including a Caucasian spotted panther, a southern lion, bulls, a horse, birds, and a shaggy animal (bear? goat?) mounting a tree (figure 12.10). The engraved horse is the oldest clear image of a post-glacial horse, and it looked like a modern Przewalski: thick neck, big head, erect mane, and thick, strong legs. The chieftan also had arsenical bronze tools and weapons. They included a sleeved axe, a hoe-like adze, an axe-adze, a broad spatula-shaped metal blade 47 cm long with rivets for the attachment of a handle, and two square-sectioned bronze chisels with round-sectioned butts. Beside him was a bundle of six (or possibly eight) hollow silver tubes about 1 m long. They might have been silver casings for a set of six (or eight) wooden staffs, perhaps for holding up a tent that shaded the chief. Long-horned bulls, two of solid silver and two of solid gold, were slipped over four of the silver casings through holes in the middle of the bulls, so that when the staffs were erect the bulls looked out at the visitor. Each bull figure was sculpted first in wax; very fine clay was then pressed around the wax figure; this clay was next wrapped in a heavier clay envelope; and, finally, the clay was fired and the wax burned off—the lost wax method for making a complicated metal-casting mold. The Maikop chieftain’s grave contained the first objects made this way in the North Caucasus. Like the potters wheel, the arsenical bronze, and the animal procession motifs engraved on two silver cups, these innovations came from the south.26  The Maikop chieftan was buried wearing Mesopotamian symbols of power—the lion paired with the bull—although he probably never saw a lion. Lion bones are not found in the North Caucasus. His tunic had sixty-eight golden lions and nineteen golden bulls applied to its surface. Lion and bull figures were prominent in the iconography of Uruk Mesopotamia, Hacinebi, and Arslantepe. Around his neck and shoulders were 60 beads of turquoise, 1,272 beads of carnelian, and 122 golden beads. Under his skull was a diadem with five golden rosettes of five petals each on a band of gold pierced at the ends. The rosettes on the Maikop diadem had no local prototypes or parallels but closely resemble the eight-petaled rosette seen in Uruk art. The turquoise almost certainly came from northeastern Iran near Nishapur or from the Amu Darya near the trade settlement of Sarazm in modern Tajikistan, two regions famous in antiquity for their turquoise. The red carnelian came from western Pakistan and the lapis lazuli from eastern Afghanistan. Because of the absence of cemeteries in Uruk Mesopotamia, we do not know much about the decorations worn there. The abundant personal ornaments at Maikop, many of them traded up the Euphrates through eastern Anatolia, probably were not made just for the barbarians. They provide an eye-opening glimpse of the kinds of styles that must have been seen in the streets and temples of Uruk. |

|

|

|

Post by Admin on May 9, 2018 18:30:35 GMT

The Age and Development of the Maikop Culture The relationship between Maikop and Mesopotamia was misunderstood until just recently. The extraordinary wealth of the Maikop culture seemed to fit comfortably in an age of ostentation that peaked around 2500 BCE, typified by the gold treasures of Troy II and the royal “death-pits” of Ur in Mesopotamia. But since the 1980s it has slowly become clear that the Maikop chieftain’s grave probably was constructed about 3700–3400 BCE, during the Middle Uruk period in Mesopotamia—a thousand years before Troy II. The archaic style of the Maikop artifacts was recognized in the 1920s by Rostovtseff, but it took radiocarbon dates to prove him right. Rezepkin’s excavations at Klady in 1979–80 yielded six radiocarbon dates averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE (on human bone, so possibly a couple of centuries too old because of old carbon contamination from fish in the diet). These dates were confirmed by three radiocarbon dates also averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE at the early Maikop-culture settlement of Galugai, excavated by S. Korenevskii between 1985 and 1991 (on animal bone and charcoal, so probably accurate). Galugai’s pot types and metal types were exactly like those in the Maikop chieftain’s grave, the type site for early Maikop. Graves in kurgan 32 at Ust-Dzhegutinskaya that were stylistically post-Maikop were radiocarbon dated about 3000–2800 BCE. These dates showed that Maikop was contemporary with the first cities of Middle and Late Uruk-period Mesopotamia, 3700–3100 BCE, an extremely surprising discovery.27  The radiocarbon dates were confirmed by an archaic cylinder seal found in an early Maikop grave excavated in 1984 at Krasnogvardeiskoe, about 60 km north of the Maikop chieftain’s grave. This grave contained an east Anatolian agate cylinder seal engraved with a deer and a tree of life. Similar images appeared on stamp seals at Degirmentepe in eastern Anatolia before 4000 BCE, but cylinder seals were a later invention, appearing first in Middle Uruk Mesopotamia. The one from the kurgan at Kransogvardeiskoe (Red Guards), perhaps worn as a bead, is among the oldest of the type (see figure 12:10).28 The Maikop chieftain’s grave is the type site for the early Maikop period, dated between 3700 and 3400 BCE. All the richest graves and hoards of the early period were in the Kuban River region, but the innovations in funeral ceremonies, arsenical bronze metallurgy, and ceramics that defined the Maikop culture were shared across the North Caucasus piedmont to the central plateau and as far as the middle Terek River valley. Galugai on the middle Terek River was an early Maikop settlement, with round houses 6–8 m in diameter scattered 10–20 m apart along the top of a linear ridge. The estimated population was less than 100 people. Clay, bell-shaped loom weights indicated vertical looms; four were found in House 2. The ceramic inventory consisted largely of open bowls (probably food bowls) and globular or elongated, round-bodied pots with everted rims, fired to a reddish color; some of these were made on a slow wheel. Cattle were 49% of the animal bones, sheep-goats were 44%, pigs were 3%, and horses (presumably horses that looked like the one engraved on the Maikop silver cup) were 3%. Wild boar and onagers were hunted only occasionally. Horse bones appeared in other Maikop settlements, in Maikop graves (Inozemstvo kurgan contained a horse jaw), and in Maikop art, including a frieze of nineteen horses painted in black and red colors on a stone wall slab inside a late Maikop grave at Klady kurgan 28 (figure 12.11). The widespread appearance of horse bones and images in Maikop sites suggested to Chernykh that horseback riding began in the Maikop period.29  The late phase of the Maikop culture probably should be dated about 3400–3000 BCE, and the radiocarbon dates from Klady might support this if they were corrected for reservoir effects. Having no 15N measurements from Klady, I don’t know if this correction is justified. The type sites for the late Maikop phase are Novosvobodnaya kurgan 2, located southeast of Maikop in the Farsa River valley, excavated by N. I. Veselovskii in 1898; and Klady (figure 12.11), another kurgan cemetery near Novosvobodnaya, excavated by A. D. Rezepkin in 1979–80. Rich graves containing metals, pottery, and beads like Novosvobodnaya and Klady occurred across the North Caucasus piedmont, including the central plateau (Inozemtsvo kurgan, near Mineralnyi Vody) and in the Terek drainage (Nalchik kurgan). Unlike the sunken grave chamber at Maikop, most of these graves were built on the ground surface (although Nalchik had a sunken grave chamber); and, unlike the timber-roofed Maikop grave, their chambers were constructed entirely of huge stones. In Novosvobodnaya-type graves the central and attendant/gift grave compartments were divided, as at Maikop, but the stone dividing wall was pierced by a round hole. The stone walls of the Nalchik grave chamber incorporated carved stone stelae like those of the Mikhailovka I and Kemi-Oba cultures (see figure 13.11). Arsenical bronze tools and weapons were much more abundant in the richest late Maikop graves of the Klady-Novosvobodnaya type than they were in the Maikop chieftain’s grave. Grave 5 in Klady kurgan 31 alone contained fifteen heavy bronze daggers, a sword 61 cm long (the oldest sword in the world), three sleeved axes and two cast bronze hammer-axes, among many other objects, for one adult male and a seven-year-old child (see figure 12.11). The bronze tools and weapons in other Novosvobodnaya-phase graves included cast flat axes, sleeved axes, hammer-axes, heavy tanged daggers with multiple midribs, chisels, and spearheads. The chisels and spearheads were mounted to their handles the same way, with round shafts hammered into four-sided contracting bases that fit into a V-shaped rectangular hole on the handle or spear. Ceremonial objects included bronze cauldrons, long-handled bronze dippers, and two-pronged bidents (perhaps forks for retrieving cooked meats from the cauldrons). Ornaments included beads of carnelian from western Pakistan, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, gold, rock crystal, and even a bead from Klady made of a human molar sheathed in gold (the first gold cap!). Late Maikop graves contained several late metal types—bidents, tanged daggers, metal hammer-axes, and a spearhead with a tetrahedral tang—that did not appear at Maikop or in other early sites. Flint arrowheads with deep concave bases also were a late type, and black burnished pots had not been in earlier Maikop graves.30 |

|