Post by Admin on May 11, 2018 18:31:54 GMT

The Age and Development of the Maikop Culture

The relationship between Maikop and Mesopotamia was misunderstood until just recently. The extraordinary wealth of the Maikop culture seemed to fit comfortably in an age of ostentation that peaked around 2500 BCE, typified by the gold treasures of Troy II and the royal “death-pits” of Ur in Mesopotamia. But since the 1980s it has slowly become clear that the Maikop chieftain’s grave probably was constructed about 3700–3400 BCE, during the Middle Uruk period in Mesopotamia—a thousand years before Troy II. The archaic style of the Maikop artifacts was recognized in the 1920s by Rostovtseff, but it took radiocarbon dates to prove him right. Rezepkin’s excavations at Klady in 1979–80 yielded six radiocarbon dates averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE (on human bone, so possibly a couple of centuries too old because of old carbon contamination from fish in the diet). These dates were confirmed by three radiocarbon dates also averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE at the early Maikop-culture settlement of Galugai, excavated by S. Korenevskii between 1985 and 1991 (on animal bone and charcoal, so probably accurate). Galugai’s pot types and metal types were exactly like those in the Maikop chieftain’s grave, the type site for early Maikop. Graves in kurgan 32 at Ust-Dzhegutinskaya that were stylistically post-Maikop were radiocarbon dated about 3000–2800 BCE. These dates showed that Maikop was contemporary with the first cities of Middle and Late Uruk-period Mesopotamia, 3700–3100 BCE, an extremely surprising discovery.27

The radiocarbon dates were confirmed by an archaic cylinder seal found in an early Maikop grave excavated in 1984 at Krasnogvardeiskoe, about 60 km north of the Maikop chieftain’s grave. This grave contained an east Anatolian agate cylinder seal engraved with a deer and a tree of life. Similar images appeared on stamp seals at Degirmentepe in eastern Anatolia before 4000 BCE, but cylinder seals were a later invention, appearing first in Middle Uruk Mesopotamia. The one from the kurgan at Kransogvardeiskoe (Red Guards), perhaps worn as a bead, is among the oldest of the type (see figure 12:10).28

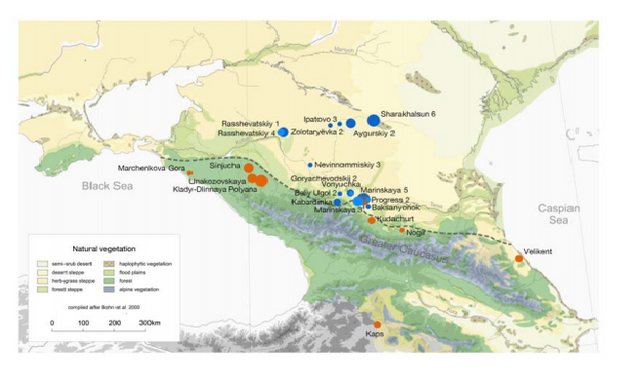

The Maikop chieftain’s grave is the type site for the early Maikop period, dated between 3700 and 3400 BCE. All the richest graves and hoards of the early period were in the Kuban River region, but the innovations in funeral ceremonies, arsenical bronze metallurgy, and ceramics that defined the Maikop culture were shared across the North Caucasus piedmont to the central plateau and as far as the middle Terek River valley. Galugai on the middle Terek River was an early Maikop settlement, with round houses 6–8 m in diameter scattered 10–20 m apart along the top of a linear ridge. The estimated population was less than 100 people. Clay, bell-shaped loom weights indicated vertical looms; four were found in House 2. The ceramic inventory consisted largely of open bowls (probably food bowls) and globular or elongated, round-bodied pots with everted rims, fired to a reddish color; some of these were made on a slow wheel. Cattle were 49% of the animal bones, sheep-goats were 44%, pigs were 3%, and horses (presumably horses that looked like the one engraved on the Maikop silver cup) were 3%. Wild boar and onagers were hunted only occasionally. Horse bones appeared in other Maikop settlements, in Maikop graves (Inozemstvo kurgan contained a horse jaw), and in Maikop art, including a frieze of nineteen horses painted in black and red colors on a stone wall slab inside a late Maikop grave at Klady kurgan 28 (figure 12.11). The widespread appearance of horse bones and images in Maikop sites suggested to Chernykh that horseback riding began in the Maikop period.29

The late phase of the Maikop culture probably should be dated about 3400–3000 BCE, and the radiocarbon dates from Klady might support this if they were corrected for reservoir effects. Having no 15N measurements from Klady, I don’t know if this correction is justified. The type sites for the late Maikop phase are Novosvobodnaya kurgan 2, located southeast of Maikop in the Farsa River valley, excavated by N. I. Veselovskii in 1898; and Klady (figure 12.11), another kurgan cemetery near Novosvobodnaya, excavated by A. D. Rezepkin in 1979–80. Rich graves containing metals, pottery, and beads like Novosvobodnaya and Klady occurred across the North Caucasus piedmont, including the central plateau (Inozemtsvo kurgan, near Mineralnyi Vody) and in the Terek drainage (Nalchik kurgan). Unlike the sunken grave chamber at Maikop, most of these graves were built on the ground surface (although Nalchik had a sunken grave chamber); and, unlike the timber-roofed Maikop grave, their chambers were constructed entirely of huge stones. In Novosvobodnaya-type graves the central and attendant/gift grave compartments were divided, as at Maikop, but the stone dividing wall was pierced by a round hole. The stone walls of the Nalchik grave chamber incorporated carved stone stelae like those of the Mikhailovka I and Kemi-Oba cultures (see figure 13.11).

Arsenical bronze tools and weapons were much more abundant in the richest late Maikop graves of the Klady-Novosvobodnaya type than they were in the Maikop chieftain’s grave. Grave 5 in Klady kurgan 31 alone contained fifteen heavy bronze daggers, a sword 61 cm long (the oldest sword in the world), three sleeved axes and two cast bronze hammer-axes, among many other objects, for one adult male and a seven-year-old child (see figure 12.11). The bronze tools and weapons in other Novosvobodnaya-phase graves included cast flat axes, sleeved axes, hammer-axes, heavy tanged daggers with multiple midribs, chisels, and spearheads. The chisels and spearheads were mounted to their handles the same way, with round shafts hammered into four-sided contracting bases that fit into a V-shaped rectangular hole on the handle or spear. Ceremonial objects included bronze cauldrons, long-handled bronze dippers, and two-pronged bidents (perhaps forks for retrieving cooked meats from the cauldrons). Ornaments included beads of carnelian from western Pakistan, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, gold, rock crystal, and even a bead from Klady made of a human molar sheathed in gold (the first gold cap!). Late Maikop graves contained several late metal types—bidents, tanged daggers, metal hammer-axes, and a spearhead with a tetrahedral tang—that did not appear at Maikop or in other early sites. Flint arrowheads with deep concave bases also were a late type, and black burnished pots had not been in earlier Maikop graves.30

The relationship between Maikop and Mesopotamia was misunderstood until just recently. The extraordinary wealth of the Maikop culture seemed to fit comfortably in an age of ostentation that peaked around 2500 BCE, typified by the gold treasures of Troy II and the royal “death-pits” of Ur in Mesopotamia. But since the 1980s it has slowly become clear that the Maikop chieftain’s grave probably was constructed about 3700–3400 BCE, during the Middle Uruk period in Mesopotamia—a thousand years before Troy II. The archaic style of the Maikop artifacts was recognized in the 1920s by Rostovtseff, but it took radiocarbon dates to prove him right. Rezepkin’s excavations at Klady in 1979–80 yielded six radiocarbon dates averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE (on human bone, so possibly a couple of centuries too old because of old carbon contamination from fish in the diet). These dates were confirmed by three radiocarbon dates also averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE at the early Maikop-culture settlement of Galugai, excavated by S. Korenevskii between 1985 and 1991 (on animal bone and charcoal, so probably accurate). Galugai’s pot types and metal types were exactly like those in the Maikop chieftain’s grave, the type site for early Maikop. Graves in kurgan 32 at Ust-Dzhegutinskaya that were stylistically post-Maikop were radiocarbon dated about 3000–2800 BCE. These dates showed that Maikop was contemporary with the first cities of Middle and Late Uruk-period Mesopotamia, 3700–3100 BCE, an extremely surprising discovery.27

The radiocarbon dates were confirmed by an archaic cylinder seal found in an early Maikop grave excavated in 1984 at Krasnogvardeiskoe, about 60 km north of the Maikop chieftain’s grave. This grave contained an east Anatolian agate cylinder seal engraved with a deer and a tree of life. Similar images appeared on stamp seals at Degirmentepe in eastern Anatolia before 4000 BCE, but cylinder seals were a later invention, appearing first in Middle Uruk Mesopotamia. The one from the kurgan at Kransogvardeiskoe (Red Guards), perhaps worn as a bead, is among the oldest of the type (see figure 12:10).28

The Maikop chieftain’s grave is the type site for the early Maikop period, dated between 3700 and 3400 BCE. All the richest graves and hoards of the early period were in the Kuban River region, but the innovations in funeral ceremonies, arsenical bronze metallurgy, and ceramics that defined the Maikop culture were shared across the North Caucasus piedmont to the central plateau and as far as the middle Terek River valley. Galugai on the middle Terek River was an early Maikop settlement, with round houses 6–8 m in diameter scattered 10–20 m apart along the top of a linear ridge. The estimated population was less than 100 people. Clay, bell-shaped loom weights indicated vertical looms; four were found in House 2. The ceramic inventory consisted largely of open bowls (probably food bowls) and globular or elongated, round-bodied pots with everted rims, fired to a reddish color; some of these were made on a slow wheel. Cattle were 49% of the animal bones, sheep-goats were 44%, pigs were 3%, and horses (presumably horses that looked like the one engraved on the Maikop silver cup) were 3%. Wild boar and onagers were hunted only occasionally. Horse bones appeared in other Maikop settlements, in Maikop graves (Inozemstvo kurgan contained a horse jaw), and in Maikop art, including a frieze of nineteen horses painted in black and red colors on a stone wall slab inside a late Maikop grave at Klady kurgan 28 (figure 12.11). The widespread appearance of horse bones and images in Maikop sites suggested to Chernykh that horseback riding began in the Maikop period.29

The late phase of the Maikop culture probably should be dated about 3400–3000 BCE, and the radiocarbon dates from Klady might support this if they were corrected for reservoir effects. Having no 15N measurements from Klady, I don’t know if this correction is justified. The type sites for the late Maikop phase are Novosvobodnaya kurgan 2, located southeast of Maikop in the Farsa River valley, excavated by N. I. Veselovskii in 1898; and Klady (figure 12.11), another kurgan cemetery near Novosvobodnaya, excavated by A. D. Rezepkin in 1979–80. Rich graves containing metals, pottery, and beads like Novosvobodnaya and Klady occurred across the North Caucasus piedmont, including the central plateau (Inozemtsvo kurgan, near Mineralnyi Vody) and in the Terek drainage (Nalchik kurgan). Unlike the sunken grave chamber at Maikop, most of these graves were built on the ground surface (although Nalchik had a sunken grave chamber); and, unlike the timber-roofed Maikop grave, their chambers were constructed entirely of huge stones. In Novosvobodnaya-type graves the central and attendant/gift grave compartments were divided, as at Maikop, but the stone dividing wall was pierced by a round hole. The stone walls of the Nalchik grave chamber incorporated carved stone stelae like those of the Mikhailovka I and Kemi-Oba cultures (see figure 13.11).

Arsenical bronze tools and weapons were much more abundant in the richest late Maikop graves of the Klady-Novosvobodnaya type than they were in the Maikop chieftain’s grave. Grave 5 in Klady kurgan 31 alone contained fifteen heavy bronze daggers, a sword 61 cm long (the oldest sword in the world), three sleeved axes and two cast bronze hammer-axes, among many other objects, for one adult male and a seven-year-old child (see figure 12.11). The bronze tools and weapons in other Novosvobodnaya-phase graves included cast flat axes, sleeved axes, hammer-axes, heavy tanged daggers with multiple midribs, chisels, and spearheads. The chisels and spearheads were mounted to their handles the same way, with round shafts hammered into four-sided contracting bases that fit into a V-shaped rectangular hole on the handle or spear. Ceremonial objects included bronze cauldrons, long-handled bronze dippers, and two-pronged bidents (perhaps forks for retrieving cooked meats from the cauldrons). Ornaments included beads of carnelian from western Pakistan, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, gold, rock crystal, and even a bead from Klady made of a human molar sheathed in gold (the first gold cap!). Late Maikop graves contained several late metal types—bidents, tanged daggers, metal hammer-axes, and a spearhead with a tetrahedral tang—that did not appear at Maikop or in other early sites. Flint arrowheads with deep concave bases also were a late type, and black burnished pots had not been in earlier Maikop graves.30